For the first time in the history of Poland’s post-Cold War democracy a political party has managed to achieve an outright majority, albeit not sufficiently large to change the constitution. The party in question is Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS), where the person who pulls the strings, Jarosław Kaczyński, occupies neither the country’s presidency nor the leadership of the government. But the PiS has started to control the news media and tinker with rules governing the judiciary, especially the Constitutional Court, to prevent the latter from creating hurdles to the social, religious, economic and international aspects of its conservative agenda. Alarm bells have started to ring in the EU, particularly in light of the fact that, in neighbouring Hungary, Viktor Orbán is also presiding over a return to authoritarianism of the kind that for some time has been labelled “illiberal democracy”. This term was given widespread currency by Fareed Zakaria in 1997. Asked as to whether this was his intention, Kaczyński himself replied: “Exactly!”. Poland is following the example of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, but matters more. It has the sixth-largest population in the EU and an economy that is growing. What can the EU do? What is it doing?

The futile diplomatic sanctions that the EU imposed on Austria in 2000 in response to the right-winger Jörg Haider’s participation in government are now a distant memory. Since then the EU has armed itself with new weapons. The main one is article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (consolidated version), although in fact it had previously featured in the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997 (precisely in anticipation of some of the possible consequences of the Union’s expansion eastwards). It is extremely difficult to apply, since it requires the involvement of the Council, the European Parliament and the Commission, at the end of which, if large majorities confirm the existence of “a clear risk of a serious breach” of democratic values on the part of a member State and it is determined that the breach is “serious and persistent”, the voting rights of that State may be suspended by the unanimous vote of the rest (not including the country in question). Neither the suspension of membership nor the expulsion of the State are provided for (although voluntary departure is countenanced). Matters would be unlikely to get this far, and obtaining the required degree of unanimity is even less likely (and not only because Orbán, and others, would not let Poland down). Setting this procedure in train is known as the “nuclear option” in Brussels.

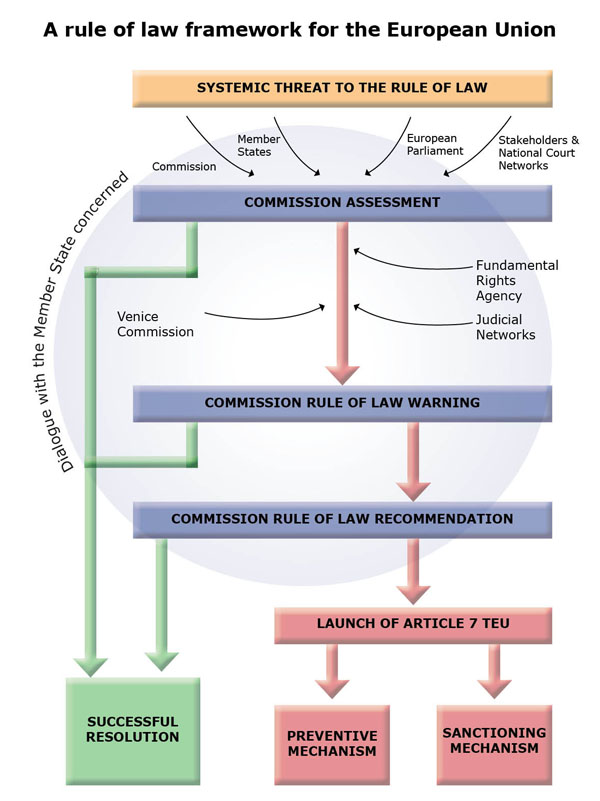

For this reason, in 2014 the European Commission, then under the presidency of Durão Barroso, furnished itself with an intermediate option, known as the “new EU framework to strengthen the Rule of Law”, and this is what the Juncker Commission has started to implement in the case of Poland. For the time being, and on this basis, the Commission has instigated a fact-finding procedure against Warsaw, which may or may not lead to finding a systemic threat to the rule of law in the country, and from there to a complex series of steps (as shown in the figure 1) that could finally lead to Article 7 being invoked. The task at the moment is to engage in dialogue with Warsaw so as to provide some recommendations for change in the areas at issue.

When the Fidesz party in Hungary had a large enough majority it amended the Constitution in an illiberal direction. The Commission took a different line against Budapest: after Orbán’s government forced 274 judges it regarded as contrary to its interests to take early retirement, throwing the separation of powers into question, the Commission took it to the EU Court of Justice. And won. But the Hungarian government offered compensation to the judges concerned, which they accepted without returning to the bench. In other words, for practical purposes no change was achieved.

The problem of illiberal reaction in the EU is on the increase, and may end up affecting not only the member States in the East but also the western half of the EU, with the flourishing of populism. The case of Poland is central, because as well as being a large-intermediate country (like Spain), according to the latest Eurobarometer report, a majority (55%) of its population continues to support the EU, in contrast to the Hungarians (39%, although the EU average is 37%). Furthermore, as Agata Gostyńska-Jakubowska of the Centre for European Reform in London points out, the Polish PiS party is a member of the same group in the European Parliament as the British Conservatives (the ECR), while Orbán’s Fidesz is in the European People’s Party (EPP), the largest grouping, meaning that it can count on more support. Besides, Poland is moving away from Germany.

As has been pointed out previously, contributing to these trends, among other factors, is the fact that these countries feel marginalised from the EU, but also that, unlike Greece, Spain and Portugal, they did not join to underpin their transitions to democracy. The effect of the Commission’s initiative remains to be seen, but a system of closer oversight of these illiberal tendencies in the EU is probably called for. Allowing them to continue unchecked could undermine democracy in the Union as a whole, and its individual member States, as well as depriving the EU of credibility when it seeks to defend its values further afield.