After years of treating it as a ‘strategic partner’, the European Commission has released a strategy document, with the formal backing of the European Council, describing China as an ‘economic competitor’ and a ‘systemic rival’. The veil has been lifted from what Emmanuel Macron has called ‘Europe’s naivety’ towards China, although this does not translate into the EU being more united on the Asian giant. The alleged naivety stemmed largely from a distorted view of world history regarding the return of China and Asia, which was attributable, at the start of the century, to a yearning for access to a vast and burgeoning market and, since the 2008 crisis, to a need for financing and investment, when China was the most willing source. The veil was lifted with the acquisition of the cutting-edge German robot company Kuka by the Chinese firm Midea, before Trump’s installation in the White House. The EU has now established a system for overseeing non-EU acquisitions of strategic European companies, aimed especially at China.

As well as US pressure, communication blunders committed by Xi Jinping have also contributed to lifting the veil. Indeed, by straying from the cautious and discreet path pursued first by Deng Xiaoping, (‘hide your capacities; bide your time’) and subsequently by Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao until 2013, with their idea of ‘peaceful rise’, Xi has revealed his goal too openly. For instance, with the publication of the Made in China 2025 strategy aimed at propelling his country to the forefront of global technology, a text that was not supposed to receive so much publicity. And for more than five years now there has been the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the great intercontinental geopolitical and geo-economic connectivity and infrastructure project (with ramifications in Latin America and Africa). BRI has elicited enthusiasm from the countries on the receiving end of its loans –not donations– and potential contractors, but also misgivings and resentment in many quarters, from Washington to Indonesia. It is essentially a strategy for Eurasia. The ports of the Mediterranean and their capitals are the focus of Chinese interest, from Piraeus in Greece to Sines in Portugal; as Bruno Maçaes of the Hudson Institute argues, the aim is to reduce its transport costs, rivalling northern European routes and reconfiguring Europe’s internal trade. The European plan drawn up in response, the Strategy on Connecting Europe and Asia, is much less ambitious.

But has the EU decided on a united stance, let alone a vision, for China? Despite appearances, it cannot be said that it has. The European countries and the EU need China, including its market and technology. And China needs the EU for similar reasons and to balance the US. Many Europeans are separately going to attend the second BRI summit in Beijing at the end of the month. There is still competition for contracts. Beijing likes to work bilaterally with the various European countries, all the better to drive in its wedges. In this context, Xi Jinping’s most recent visits to southern Europe are significant, following his wooing of central and eastern Europe. Italy, beset by economic woes, has moved away from the general line that Paris and Berlin have tried to impose on the EU (to which Madrid has assented) and has signed an agreement on the BRI. It is the 13th EU country to have done so, but the first in the G7. For the Italian government it is also a way of demonstrating its defiance of the EU, and specifically of Germany.

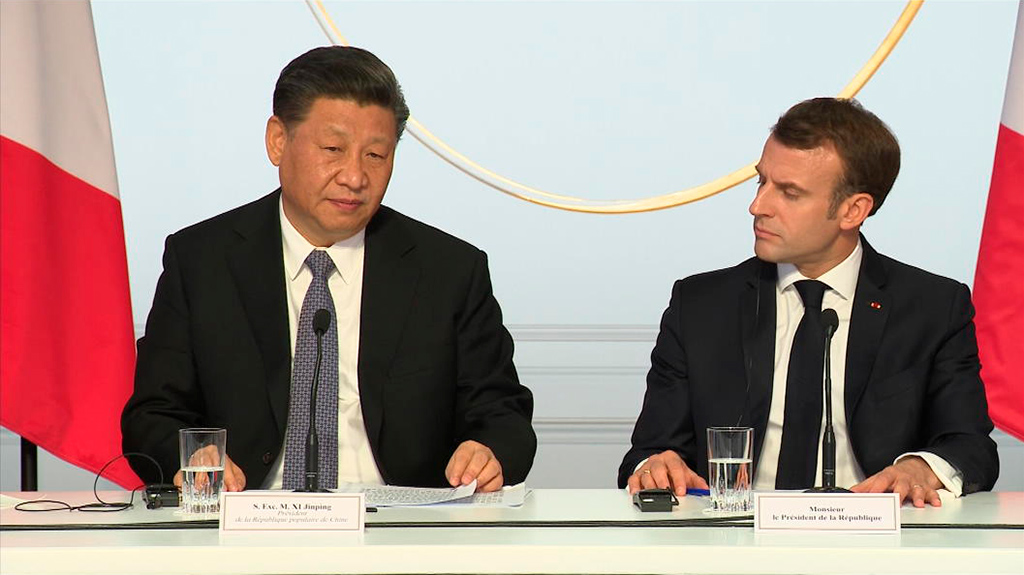

By welcoming the Chinese President in Paris last week –marking another important phase– Macron tried to signal European unity, inviting the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, and the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, to talks with Xi Jinping about multilateralism and opening up reciprocal trade, which probably carries greater symbolic weight than the forthcoming EU-China summit on 9 April in Brussels with the Prime Minister, Li Keqiang. But in the bilateral declaration released after the meeting between Macron and Xi, signed by two permanent members of the UN Security Council, France ‘overlooked’ any mention of the EU. And the human rights issue is now barely brought up by the Europeans in their talks with China. The EU keeps such values essentially for internal purposes. And so it goes on.

The EU’s relations with China are also conditioned by those between Beijing and Washington, replete with rough edges. The EU fears a trade and technological confrontation between the US and China, but also that a possible trade agreement between the two great economic powers will be to the detriment of Europe. On the issue of the fifth generation of mobile telephony, known as 5G, many European companies are committed to better and cheaper Chinese technology (essentially from Huawei and ZTE), where they have already invested considerably and which would enable them to have earlier access to this major new communications revolution, this time geared more towards the internet of things. Citing security, the US is putting pressure on the Europeans to refrain from such Chinese supplies and adopt American alternatives (also partly European in the form of Nokia and Ericsson). The Commission wants a united response and is requesting national investigations of the possible security threats and a European plan in less than four months. Will Europe be in a position to be able to choose, in geopolitical and technological terms? It remains to be seen.

Beyond the official line –set out in a strategy that this time has been approved for publication and distribution– Beijing sees the EU as weakened by many factors, despite Macron’s calls for ‘European sovereignty’, including digital sovereignty. In 2018 however, the majority of Chinese foreign investments in the IT industry and technologies went to Europe, partly because doors were closed to them in the US. It may be that the veil of European naivety has fallen, but the reality of the interdependence is still abundantly clear. That said, one needs to know how to manage it.