Dates that for decades have commemorated significant events, particularly tragic ones, such as Remembrance Day in the UK (commonly known as Poppy Day) on 11 November, when the country remembers those who died in the two World Wars and subsequent conflicts, are sacred and never moved.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s President, has broken with this tradition as he is commemorating with great fanfare the 1915 victory at Gallipoli, which this year coincides with the 100th anniversary of the events known as the Armenian genocide, which reduced the population of Ottoman Armenians by more than 1 million.

The Gallipoli commemorations kicked off in Turkey on 18 March, the day a British-French naval force entered the Dardanelles Straits in a bid to take Constantinople (now known as Istanbul), and was repulsed by ‘heroic’ Turkish guns. This has traditionally been the key date for Turkey, while April 25 is commemorated by Australia and New Zealand (ANZAC Day), thousands of whose troops died at Gallipoli. This year, however, Turkey is also holding ceremonies on 24 April, the very same day that has long marked the start of the Armenian tragedy.

Erdogan invited his Armenian counterpart Serzh Sarkisian, along with more than 100 world leaders, to the Gallipoli ceremony on 24 April after himself receiving an earlier request from Sarkissian to attend the events marking the Armenian genocide –a term successive Turkish governments have vehemently refused to accept–.

Erdogan’s moving of the date amidst a growing debate about the Armenian tragedy, including in Turkey, is a clear attempt to overshadow the massacre of Armenians, widely perceived as the first genocide in the 20th century.

‘Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?’, said Adolf Hitler in 1939. The tragedy and Gallipoli are not forgotten in my wife’s family. Her grandmother was Armenian (her family left Tokat in Anatolia before the killings) and her Scottish grandfather was wounded in Gallipoli. She nursed him in Alexandria and they married.

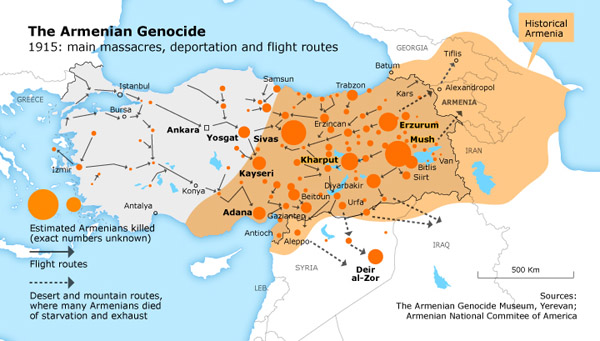

The province of Sivas, adjacent to Tokat, suffered considerably: its population dropped from 225,000 in 1914 to 16,800 in 1922, according to figures we saw displayed in the Genocide Museum in Yerevan.

Turkey goes to the polls on 7 June. Erdogan is courting the nationalist vote. His Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) needs to win two-thirds of the seats if Erdogan is to have his way and his party, on its own, change the constitution in order to give greater powers to the presidency. The AKP currently has 312 of the 550 seats in the Grand National Assembly (57%).

The centenary has been marked by the publication of two fair-minded books: neither Thomas de Waal in The Great Catastrophe (Oxford University Press) or Ronald Grigor Suny in A History of the Armenian Genocide (Princeton University Press), however, find a ‘smoking gun’ that would enable clear premeditation to be attributed to those responsible. This would enable the perpetrators to be convicted retroactively under the 1948 UN Genocide Convention, which defines genocide as ‘acts committed with intent to destroy in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group’ (italics added). This is a matter for judges, not historians.

The Young Turk leaders believed Armenians were internal enemies allied to Russia in World War One (Turkey supported Germany) plotting to win an independent state. But why were so many women and children killed or died from starvation after being deported to the desert? The separatist nationalism of the few was answered with the total destruction of the wider ethnic community from which the nationalists hailed.

The Armenian tragedy is the longest and most bitter historical debate still alive, and one that has helped to keep the Armenia-Turkey border closed since 1993. Turkey closed the frontier in support of its ally Azerbaijan, which was in conflict with Armenia over the disputed enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh. Turkey and Armenia agreed a road map in 2009 to normalise relations including the setting up of a sub-commission to examine the ‘historical dimension’ of their relations.

The Zurich Protocols were suspended in 2010 after a lack of progress. Armenian diaspora groups, more than the Armenian government, saw the commission as a ploy and opposed it as the evidence was already voluminous and well documented. The commission would have given Turkey an opportunity to re-write its official denialist version of 1915, had it wanted to. More than 20 countries including France and the Vatican, recognise the genocide. The European Parliament called on Ankara earlier this month to recognise the mass killing.

The ‘Armenian Question’ is no longer a taboo subject in Turkey. Orhan Pamuk almost went to jail in 2005, a year before winning the Nobel Prize for Literature, for making controversial comments on the killing of Armenians which led to him being charged with insulting Turkey’s national character. Alternative histories have been increasingly allowed since then, but the denialist approach has not been abandoned. Last year Erdogan offered his condolences to the families of the Armenians massacred. His remarks were the most conciliatory remarks yet and represented a big step for a Turkish leader, but they were a small one for Armenia as he stopped short of a formal apology.

Turkey has successfully consolidated itself as a nation state forged from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire at a time when the Armenians and Greeks, both of them minority Christian communities, were identified as the main threats. Other countries have fully faced up to uncomfortable episodes of their past, most notably Germany. Turkey needs to find a way to do so.