Since China began its opening to the world just over 40 years ago, the international society has witnessed the awakening of the great Asian giant, which, embracing a new slogan of “peace and development”, has burst firmly onto the global scene to transform its geopolitics and alter the balance of an increasingly multipolar environment.

In order to consolidate its position as a power with global ambitions and interests, and to project its influence beyond its national borders, China, under the chairmanship of Xi Jinping, has launched the New Silk Road, a geopolitical engineering project that has posed an enormous challenge to the world economy and a revolution in the transport infrastructure of goods, passengers, hydrocarbons and technology. In addition to revitalizing the historic land route that made trade between Europe and Asia possible for centuries, this titanic deployment also has a maritime route that allows the People’s Republic to guarantee its commercial and energy security, while endowing it with a privileged position in the naval control of Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. Thus, being aware of the instability surrounding the South Asian coast, its deep enmity with other countries in the region and the undisputed US control of most maritime routes and straits, China has promoted a policy of westward diversification that extends from the coasts of Asia to the Middle East, North Africa and Europe.

The so-called String of Pearls, made up of an extensive network of commercial ports and military bases, allows China to gain influence and prestige in the international sphere, while at the same time solving first-rate operational needs. Through the establishment of naval bases, the construction of air and port facilities and the signing of investment and economic cooperation agreements, China has managed to secure the supply of the resources necessary for its development, has forged new commercial relations that have repercussions on the growth of its exports and has fulfilled its objective of preserving national security by projecting a naval power capable of defending its interests far from its territory.

Although this complex network has several cornerstones of great geopolitical relevance spread over the five continents, such as the port of Gwadar, which gives access to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the logistics centre established in the port town of Dolareh, on the north coast of Djibouti, is perhaps the brightest pearl in the Chinese string, as it is also China’s first permanent military installation abroad.

The People’s Liberation Army Support Base, which began construction in 2016 and was inaugurated only a year later, has an overall cost of US$590 million, a surface area of 500 m2, more than 20,000 m2 of underground space and the potential to harbour 10,000 effectives, although it is currently estimated that only a thousand of them have been deployed. Despite having been defined by the government of Beijing as a mere support facility, it is predicted that the base will also be playing a major role in other high-level endeavours of Chinese foreign policy such as:

- Providing maintenance and military assistance to Chinese contingents deployed in humanitarian missions across the African continent, which until now had to return to China to stock up;

- Protecting the one million Chinese citizens residing in Africa who could potentially need to be evacuated as non-combatant personnel in the event of an armed conflict or natural disaster;

- Intelligence gathering, communications control and monitoring of the political and commercial activities of other countries in the region.

The choice of this remote enclave of the Horn of Africa as host country responds to a careful assessment of China’s geostrategic needs. Firstly, despite sharing borders with Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea, Djibouti has established itself as the safest and most stable country in a conflictive but strategically important area. Moreover, the Horn of Africa, flanked by the Red Sea and the Aden Sea, is home to the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, one of the most important sea routes for trade and energy transport in the world, concentrating up to 25% of world exports and serving as a transit point for around 30% of the oil heading west. Due to its rugged orography, Bab el-Mandeb offers very few alternative routes of passage in the event of a collapse or closure, forcing those who transit it to border the Cape of Good Hope, with the incalculable increase in expense that this would imply.

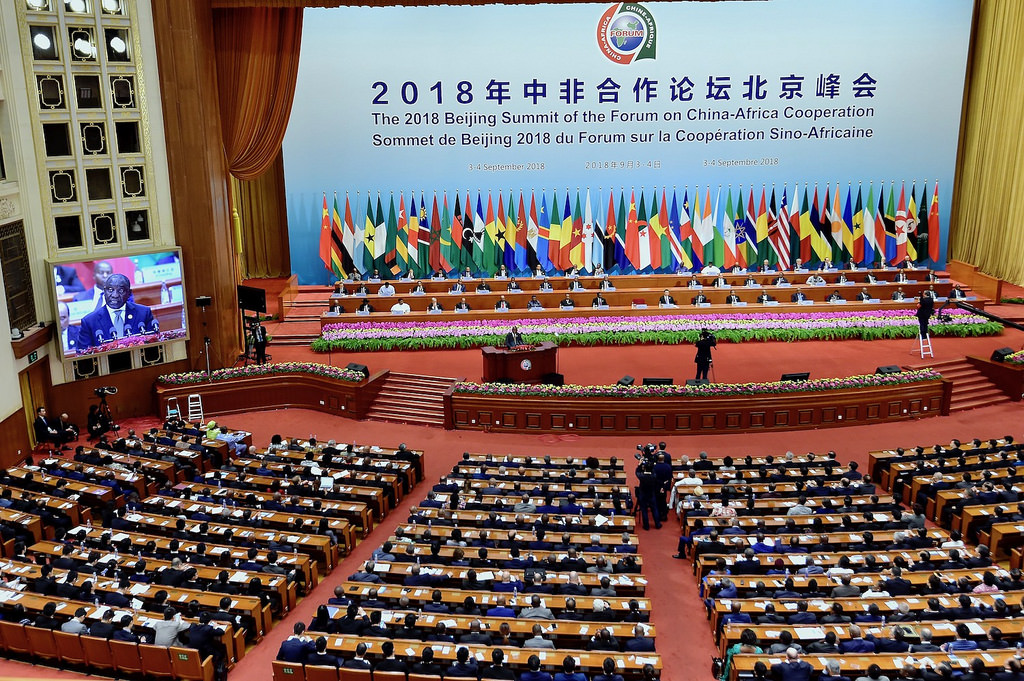

The enormous potential offered by the African continent has not gone unnoticed by China, which has made it the preferred scenario for projecting its new model of world leadership within the framework of the New Silk Road. Although China has been accused of exercising some sort of neo-colonialism in Africa, its authorities assure that it is a horizontal and very beneficial partnership for a continent formerly forgotten and exploited by the West. In just a few decades, China’s presence in Africa has meant an accumulated investment of US$100 billion that translate into financing of projects to build 30,000 kilometres of highways, generate 20,000 megawatts of electricity, create around 900,000 local jobs and purify more than nine million tons of water a day. In addition, China has promoted the construction and renovation of more than 6,000 kilometres of railroad in countries like Angola, Nigeria, Ethiopia or Sudan, and it is expected that they will soon begin the construction of a new railroad route that will connect the port of Dakar, with direct exit to the Atlantic, with the port of Djibouti, where China has assured its connection with the Indian Ocean.

Under the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, which acquires a holistic dimension by relying on the String of Pearls and the Maritime Silk Road, China has developed a multidisciplinary foreign policy that brings together diplomatic, political, economic and military actions to restore the Asian dragon’s status as a world power. Therefore, the Djibouti naval base –the highest expression of China’s presence in Africa– is a clear manifestation of the effectiveness of this strategy: a hybrid combination of hard power, exercised through the participation in the world’s defence chessboard and the adoption of military agreements, and soft power, carried out through the investment in civil infrastructures and development cooperation.