Original version in Spanish: Mujeres, paz y seguridad: lejos de las aspiraciones de la Resolución 1325

Theme

The reality facing women and girls in conflict scenarios and their role in peace-building will not improve unless firmer and more decisive action as well as a clear political impetus and funding for the goals agreed in United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) are forthcoming.

Summary

October 31st this year marks the 15th anniversary of the historic UN Resolution 1325 (2000), which acknowledges the disproportionate and unique impact of armed conflict on women and girls (different from that suffered by men and boys), and the key role of women in preventing and resolving conflict, and in constructing and consolidating peace. In the light of the limited and uneven progress made, only a redoubled and permanent commitment to the ‘Women, peace and security’ agenda –one that contributes to overcoming the obstacles to progress that still exist, that embraces new challenges and emerging threats and drives concrete measures– can ensure the protection of women’s rights in conflicts, their full presence in the prevention and resolution of armed conflicts and their participation in the building of peace. Spain, which will chair the Security Council this coming October, and which has pinpointed gender equality as one of its priorities during its two-year term, has the chance, in alliance with other member states, to play a leadership role in the United Nations, which should also translate into a new National Action Plan featuring new commitments and greater coherence.

Analysis

Resolution 1325, an historic landmark

Preceded by thorough and ongoing work on the part of women’s organisations, peace campaigners and civil society organisations supportive of equality and women’s rights from various parts of the world, and by the significant commitments agreed in the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, in the year 2000 the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) recognised, for the first time, the distinct impact of armed conflict on women and girls, and the effects of this for the prevention and resolution of conflicts, as well as for lasting peace and reconciliation, and consequently for advancing international peace and security. Taking this as its basis, Resolution 1325 called for the following measures to be taken:

- That Member States should ensure increased representation of women at all decision-making levels in national, regional and international institutions and mechanisms for the prevention, management and resolution of conflict, and increase their voluntary financial, technical and logistical support for gender-sensitive training efforts.

- That the United Nations Organisation itself should appoint more women as special representatives and envoys to pursue good offices, and expand the role and contribution of women in United Nations field-based operations, and especially among military observers, human rights and humanitarian personnel.

- That all actors involved, when negotiating and implementing peace agreements, should adopt a gender perspective, including, inter alia: (a) the special needs of women and girls during repatriation and resettlement and for rehabilitation, reintegration and post-conflict reconstruction; (b) measures that support local women’s peace initiatives and indigenous processes for conflict resolution and that involve women in all of the implementation mechanisms of the peace agreements; and (c) measures that ensure the protection of and respect for human rights of women and girls, particularly as they relate to the constitution, the electoral system, the police and the judiciary.

- That all parties to an armed conflict should fully respect international law applicable to the rights and protection of women and girls, especially as civilians, and take special measures to protect women and girls from gender-based violence, particularly rape and other forms of sexual abuse.

- That all States should put an end to impunity and prosecute those responsible for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, including those relating to sexual and other violence against women and girls, drawing special attention to the need to exclude these crimes, where feasible, from amnesty provisions.

As the UN Women organisation states, ‘Resolution 1325 represents a significant change in the way the international community approaches the prevention and resolution of conflict, and makes the promotion of gender equality and women’s empowerment an international peace and security concern’. As the organisation rightly reminds us, the justice and rights-based argument (women, like men, have a right to participate in the promotion of peace) is accompanied by that of efficiency: the exclusion of half the constituency for peace-building is inefficient, and the marginalisation of women undermines every step of the process, since in many contexts women are a resource for building socially relevant and effective peace accords, and for ensuring social inclusion and a fair distribution of peace dividends.1

Bolstered by six additional resolutions chiefly addressing sexual violence in armed conflict as a weapon of war (Resolution 1820 of 2008, Resolution 1888 of 2009, Resolution 1960 of 2010 and Resolution 2106 of 2013) and the need to actively encourage and oversee compliance with the goals laid down in the year 2000 (Resolution 1889 of 2009 and Resolution 2122 of 2013), Resolution 1325 has succeeded in raising general awareness of the gender perspective as an essential element for contributing to international peace and security.

A disappointing balance sheet, with more debits than credits

There can be no question that Resolution 1325 has led to progress over the last 15 years, essentially of a normative character, both at the heart of the United Nations and in the Member States: as of June 2015, 50 States had adopted a National Action Plan2 in support of Resolution 1325, which shows that notable headway has been made (half-way through 2012, 37 countries had drawn up plans, and by November 2013 more than 80 had committed themselves to drafting them).

Resolution 1325 has led to changes in the work the United Nations conducts in peace and security, although not it all domains. Field-based operations and peace-keeping missions are supplying more and more detailed information in their reports3 on women, peace and security. Of the 47 resolutions passed by the UNSC in 2013, 76.5% contained references to women, peace and security.4 In eight of the 11 peace processes directed or co-directed by the United Nations in 2013, at least one of the negotiators was a woman, and 88% of the negotiation processes had specialist expertise in gender issues at their disposal. Considerable challenges remain, however: as of March 2014, 97% of peacekeeping military staff and 90% of the police officers were men, percentages that have not changed since 2011.5 Civil society organisations such as Human Rights Watch have also frequently pointed out the failure of the UNSC to apply the women, peace and security agenda to the ground in crisis situations, as well as the infrequent use of sanctions and other instruments at the disposal of the UNSC as a means of furthering this agenda.6

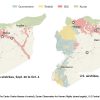

As far as the situation of women and girls is concerned, the track record for the way the Resolution 1325 goals have been pursued continues to be ethically unacceptable, clearly insufficient and reveals highly uneven progress when comparing countries: women continue to suffer, in a systematic and recurrent way, sexual violence in armed conflicts (such as in Ivory Coast, Mali, Syria, the Central African Republic, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo),7 and are victims of new forms of violence (such as that carried out by Boko Haram in Nigeria), as well as being underrepresented in peace-building and in conflict prevention and resolution. Some figures by way of illustration: out of a total of 585 peace accords signed between 1990 and 2010, barely 92 include any reference to women.8 Between 1992 and 2011, only 9% of the negotiators at peace talks were women.9 Women head only 19% of the UN’s missions on the ground.10

In addition to the challenges mentioned above there is the goal of ensuring that women account for 20% of the police officers and military personnel in peacekeeping missions, a level that is still a long way from being achieved. And although 134 countries have classified sexual slavery as a crime, the number of convictions continues to be extremely low.11 Crimes of sexual violence in conflicts are not always reported. And new forms of violence and threats against women’s rights have emerged.

Many challenges remain, not only in the field of prevention but also in terms of participation, protection and consolidation of peace; these require greater political will, which in turn needs to be translated into sufficient funding in order to produce tangible results. The United Nations denounces the ‘the alarmingly low levels of spending on consolidating peace’, but also on prevention and on reparations, which are still being systematically excluded from peace talks, and consequently from funding priorities. An appropriate and sufficient funding framework is critical for making progress.12 The mustering of resources is one of the keys to overcoming the challenges, and it will be necessary to seek formulas to ensure that, as well as being sufficient, they are sustained over time. Public-private partnerships, with the involvement of the business sector, are one option that needs to be considered. This is not to overlook the commitment of governments, international organisations and the cooperation of civil society, especially in terms of human resources and expertise.

One of the main obstacles underlying the challenges outlined above is the persistence of inequalities in the political, economic and social sphere, a factor that hampers the bridging of the gulf between men and women, even in advanced countries.13 Unless progress is made in the structural causes of gender inequality (unequal participation in public and private decision-making, lack of equal opportunities, resources and responsibilities and the violence committed against women)14 it will not be possible to improve the situation of women and girls in the domains of security and peace.

Spain’s priorities at the Security Council in the ‘Women, peace and security’ agenda

In its bid to become a member of the UNSC for the 2015-16 period, the Spanish government cited gender equality as ‘one of the main goals of Spanish foreign policy and diplomacy’, including among the 10 reasons underpinning its aspiration to become a non-permanent member of the United Nations that of ‘giving human rights, gender equality and the full participation of women in peace-building the high profile they deserve to ensure security and stability’.15

Spain will preside over the UNSC in October, coinciding with a high-level assessment to evaluate the progress made in implementing Resolution 1325. This represents a unique chance to give impetus, with tangible measures, to the priority that Spain has vowed to place on the women, peace and security agenda. The Spanish government has indicated that the review process should lead to more solid institutional architecture and leadership on the part of the United Nations in order to drive through implementation of its resolutions in this domain. It has also underscored the importance of incorporating more substantive language in this area into the UNSC’s documents, particularly those referring to the imposition of sanction regimes.

In the first few months of its biennium, Spain has taken such initiatives as convening a debate in the Security Council, using the ‘Arria-formula’ format,16 on women, peace and security with the presidents of the three panels preparing reviews on peace and security for 2015: (a) a Global Study on Resolution 1325; (b) architecture for the consolidation of peace; and (c) peace operations, with the intention of strengthening synergies and contributing to the design of an integrated focus on the themes of peace and security, ensuring the inclusion of the gender perspective.

Within the framework of an Open Debate, Spain has also proposed certain measures on sexual violence in conflict. In conflicts where no Peacekeeping Operation (PKO) has been deployed, it has requested that all the information needed to investigate suspicions of sexual violence be sent to the prosecutors at the International Criminal Court and that sexual violence be introduced, without exception, in as many of the transitional justice procedures as possible, underlining the importance of compensating the victims. In cases where a PKO has been deployed, it has proposed bolstering the PKO’s mandate with regard to women, peace and security; the requirement of a specific duration and content in the prior training of military peacekeeping personnel; the strengthening of human resources in terms of gender experts in the gender unit of the UN’s PKO Department; and an obligation on the Secretary General’s special representatives to report on this topic, in an analytical and strategic way, at every briefingto the Council.

Lastly, the Spanish government has announced its intention to propose that the Security Council adopt a new resolution that ‘defines the UNSC’s responsibility in this area, that requires results of the United Nations system and that addresses threats that are not included in Resolution 1325 and its successors, such as the role of women in the fight against violent extremism’.

This new resolution, which undoubtedly has the potential to be a good opportunity to muster greater political will on the part of the UN Member States, and to focus on the need to accelerate initiatives, will have no effect on the lives of women and girls if it does not incorporate adequate funding commitments that are sustained over time. The new resolution particularly needs to link up with the Sustainable Development Goals agenda, in which equality, as well as being fully integrated into the other 16 goals, is represented, with a series of targets, in Goal 5 of the SDGs: ‘To achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’. The priorities for the results should focus on those areas where least progress has been made, such as prevention, protection and the participation of women in peace processes, where the record to date, as indicated above, has been clearly inadequate and disappointing.

To accompany its leadership in promoting the new resolution, the Spanish government should also offer a commitment to a thorough overhaul of the National Plan, with the drawing up of a new National Action Plan, appropriately equipped with human resources and materials and the active participation of civil society organisations throughout the process. This commitment to draw up a second plan (as other countries among Spain’s regional neighbours, such as Ireland, have already done), would help to lend coherence to the initiative that is being fostered in the UN, and would address the need to have an improved Plan to accelerate and ensure the implementation of Resolution 1325.

A new more effective National Action Plan

Resolution 1325 calls on the Member States of the United Nations to incorporate its targets into national planning relating to security, defence, foreign policy, justice and the consolidation of peace with the endorsement of National Action Plans.

Spain was one of the first countries to approve a National Action Plan for implementing Resolution 1325. At that time, only the UK, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Canada, Austria and the Netherlands, apart from Spain, had adopted national plans (nine countries in the entire world, six of them members of the EU).17

Approved in November 2007, the Plan has six goals: (1) the promotion of women’s participation in peace missions, and in their decision-making bodies; (2) the inclusion of the gender perspective in all peace-building activities; (3) the specific training of personnel taking part in peace operations; (4) the protection of women’s and girls’ human rights in conflict and post-conflict zones (including refugee and displaced person camps) and the empowerment and participation of women in the processes of negotiating and applying peace accords; (5) the principle of equal opportunities and treatment for men and women in the planning and execution of activities involving disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR), as well as the special training of all the personnel who participate in such processes; and (6) the fostering of Spanish civil society’s participation with regard to Resolution 1325.

For each of these goals the Plan contains measures at the level of Spain, the EU and international organisations such as NATO, the OSCE and the United Nations. Lastly, in the chapter on monitoring and evaluation, the Plan sets out the functions of the monitoring group, made up of the ministries involved,18 and presided over by the Spanish Foreign Ministry’s Equality Policy Promotion unit (an entity that was abolished in 2011), such as setting up coordination mechanisms with civil society for exchanging information on initiatives carried out in relation to Resolution 1325, and submitting an annual follow-up report.

Eight years after it was set up, and in light of the evaluation reports drawn up by both the government itself19 and by the civil society organisations20 –which mention, among other recommendations, the need for greater coherence, and an appropriate institutional framework in each of the units involved, the need for impact-measurement mechanisms and the more active inclusion of civil society in following up on the action plan– the time has come to go beyond a mere update of the existing Plan and to contemplate drawing up a new National Action Plan.

This new Plan, which should be designed in close cooperation with civil society organisations, needs to: be adequately provisioned with human and other resources; overhaul any measures in need of being brought up to date; recalibrate the greater involvement of the Foreign Affairs and Cooperation and Defence Ministries with that of other key Ministries such as Justice, Education, Health, Employment and Interior; include impact-measurement benchmarks (already introduced both by the EU, which has a group of 17 indicators, and the United Nations);21 incorporate a post of coordinator22 to lend coherence to the ensemble of actions set in motion by each of the arms of the administration; and ensure that the evaluation process, whose follow-up report should be published annually, is carried out by civil society organisations, thereby providing the public administration with independent assessment. This ensemble of goals, incorporating some of the best available practice,23 would provide the Plan with substantially greater efficiency and scope than it has had up to now, helping to speed up the implementation of Resolution 1325.

Conclusions

As we celebrate the 15th anniversary of the historic United Nations Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security, only the introduction of tangible measures, backed by adequate and enduring resources, can cause the situation of women and children to improve. Its participation in the Security Council in the 2015-16 biennium represents a unique opportunity for Spain to drive the gender equality agenda and contribute with its commitment to speeding up the rate of progress. Steering initiatives aimed at securing effective equality in those international arenas where she has a presence is essential if Spain is to be viewed as a country that is active and committed to the cause of equality between men and women.24

The stimulus that Spain wishes to give to the review of Resolution 1325, sponsoring a new resolution at the UNSC, should help to mobilise sufficient political will and financial resources to guarantee action and to speed up the pace of change towards progress. The Spanish government’s commitment should be reflected in the National Plan, with the drawing up of a new, more ambitious Plan, equipped with human resources and funding, incorporating impact-measurement mechanisms and accountability to civil society and with its active involvement in the implementation of the Plan. Public-private partnerships could provide a formula to complement the funding that this Plan needs.

The review of Resolution 1325 needs to be comprehensively linked to the sustainable development agenda and the implementation review of the Beijing Platform for Action, Beijing +20, which aspires to achieving equality between men and women (a 50-50 planet) by 2030. Only a 50-50 planet will be capable of securing greater rates of prosperity, wellbeing, rights and liberties and peace and security. In a world as complex as ours, it would be a potent stabilising factor to add to those of economic competitiveness and fairness, demonstrating that gender equality constitutes a goal of the utmost importance in the 21st century.25

María Solanas

Project Manager at Elcano Royal Institute | @Maria_SolanasC

1 UN Women (2012), ‘Women and Peace and Security: Guidelines for National Implementation’, October.

2 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

3 According to the United Nations Secretary General’s Report on women, peace and security dated 24/IX/2014, 96% of the periodic reports submitted include references to women, peace and security.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 ‘Our rights are fundamental to peace’ (HRW). Includes concrete examples of opportunities squandered by the United Nations in the Great Lakes region in 2013 and of the sexual violence committed against women in Darfur in 2014 by the Sudanese forces.

7 Secretary General’s report, op. cit.

8 Christine Bell & C. O’Rourke (2010), ‘Peace Agreements or Pieces of Paper? The Impact of UNSC Resolution 1325 on Peace Processes and their Agreements’, International and Comparative Law Quarterly.

9 Data from UN Women.

10 Secretary General’s report, op. cit.

11 Ibid.

12 Cordaid and Global Network of Women Peacebuilders (2014), ‘Financing for the Implementation of National Action Plans on UNSCR 1325: Critical for Advancing Women’s Human Rights, Peace and Security’.

13 According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2014, Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Sweden, which occupy the first five places, have managed to close 84% of the gender gap.

14 Cristina Gallach (2015), ‘Mujeres y poder en el escenario internacional’, Política Exterior, September-October.

15 María Solanas (2014), ‘Igualdad de género y política exterior española’, EEE, nº 21/2014.

16 The Arria formula enables a member of the Security Council to invite other members to an informal debate and chair the debate so as to be able to take information from experts in an area of concern for the Security Council.

17 María Solanas (2014), op. cit.

18 At that time the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, Defence, Employment and Social Affairs, Interior Affairs, Justice, Education and Science and Health and Consumer Affairs.

19 Follow-up Reports III and IV, dated February 2014, on the implementation of the National Action Plan for Resolution 1325.

20 ‘Plan de Acción español de la Resolución 1325. Informe Seguimiento III y IV. Una valoración independiente’, May 2014, drawn up by Coordinadora ONG para el Desarrollo España, CEIM (Centro de Estudios e Investigación Mujeres), WIDE España, WILPF España and CEIPAZ.

21 Annex 3 of the UN Women manual, ‘Women and Peace and Security: Guidelines for National Implementation’, October 2012.

22 There are various formulas: in the case of the US, the Women, Peace and Security Interagency Policy Committee, created and directed by the White House national security team to implement the NAP, is the body that coordinates interaction with civil society, charged with overseeing implementation of the Plan.

23 Belgium, Liberia and the Netherlands officially submit reports to civil society organisations. Other formulas include reports to parliament. In Austria, civil society organisations have the chance to comment in an annual report.

24 María Solanas, (2014), op. cit.

25 María Solanas (2015), ‘Beijing+20: la igualdad de género ¿en 2030?’.