Theme

Spain has good reasons for wanting the best possible relationship between Britain and the EU as a result of Brexit, but it cannot allow the UK to be better off outside the EU than inside it.

Summary

The Spain-UK relation has become increasingly significant in terms of trade, direct investment, tourism, fisheries and the number of Britons living in Spain, by far the largest group of British expats in any European country.

Analysis

Overview

The Spain-UK relation can be traced back, in particular, to Catherine of Aragon, the first wife (1509-1533) of Henry VIII, although there had previously been much interaction between England and Castile. It has not always been an easy one, most notably when the Spanish Armada threatened England in 1588 and was defeated. Centuries later, when Spain joined the EU in 1986, the relation entered a secure institutional framework, except for the contentious issue of Gibraltar, the UK overseas territory perched on the southern tip of Spain and long claimed by Madrid since it was ceded to Great Britain in 1713.

Apart from the Rock, which the Socialist Prime Minister Felipe González (1982-96) called the ‘grit in the shoe’ in the Spain-UK relationship (for British ambassadors in Madrid being summoned to the Spanish Foreign Ministry on Gibraltarian issues was like ‘going to the dentist’), relations between the two countries have blossomed.

King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia will make an official visit to the UK in June, ahead of that of US President Donald Trump, and unlike Trump, unless matters change, the King will be accorded the honour of addressing a joint session of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. Their visit will be the first since that of the King’s parents, King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía, in 1986.

Brexit could be particularly ‘negative’ for Spain, according to a recent report written for the Spanish government’s Brexit commission and leaked to El País. A hard Brexit could cost the economy up to €1 billion in lost exports and have ‘innumerable repercussions’ for the 800,000 Britons living in Spain and the 300,000 Spaniards in the UK.1 It will affect everything from fishing rights to the careers of Spanish footballers playing for British football clubs and British ones for Spanish clubs.

The UK’s departure from the EU could result in Spain having to increase its EU budgetary contributions by €888 million, according to the report, and some regions in losing their European funding. This would not be welcome news for a government that only last year managed to meet the budget deficit target set by the European Commission for the first time since the onset of Spain’s economic crisis in 2007.

Well-known Spanish multinationals, such as Banco Santander, the telecoms group Telefónica and the energy giant Iberdola have made significant acquisitions in the UK and a host of smaller companies have made investments.

As regards British citizens, they play a major role in some local economies, particularly during the low tourism season. There are 74,000 Britons who live in the province of Alicante all the year round and 50,000 in Malaga, according to the British Consulate in Madrid. Their rights, particularly in health matters, are a source of a lot of concern and this is already producing a small exodus of elderly Britons back to the UK.

Close to 11,000 Spaniards are at British universities (few British undergraduates are at Spanish universities). EU citizens are entitled to study in other EU member states, pay domestic fees (in some cases less than a third of the international fees) and sometimes get student loans. When Britain leaves the EU a new arrangement with European countries regarding the rights of students will be needed.

Lastly, there is Gibraltar, which voted 96% in favour of remaining in the EU. The UK’s exit from the EU will make the Rock’s border with Spain an external and not an internal EU frontier (which as, at present, has to be kept open under EU rules). As such, Spain could close it and a legal challenge by the UK/Gibraltar would be more difficult. Some 7,000 Spanish workers cross the border every day.

Alfonso Dastis, Spain’s Foreign Minister, has made it crystal clear that any future relationship between Gibraltar and the EU must be agreed between Spain and the UK. Madrid has put on the table joint sovereignty of Gibraltar as a way for the Rock to remain in the EU, which the territory has predictably rejected.

The trade relation

Two-way trade of goods between Spain and the UK rose from €12.3 billion in 1995 to €30.2 billion in 2016, according to Spain’s Economy Ministry. Spain has enjoyed a trade surplus with the UK almost every year (close to €8 billion in 2016) since 2002 (see Figure 1).

The surge in sales to the UK helped Spain notch up a new exports record last year; Madrid is keen to keep up the momentum as exports are playing an important role in the economy’s recovery from a deep recession.

Exports of €19.15 billion to the UK last year accounted for 7.5% of the total, the third largest amount after France and Germany. The sector whose exports to the UK have increased the most is the motor industry (from €1.61 billion in 1995 to €5.43 in 2016). Spain is home to many of the major car producers including VW (which also owns Seat), Ford (the plant in Almussafes is Ford’s biggest in Europe) and PSA Peugeot Citroen. It also has a thriving auto components sector. Grupo Antolín acquired the automotive interiors division of Canadian Magna International in 2015, which reinforced its position in the UK. Exports of food, drinks and tobacco have also surged (from €950.7 million in 1995 to €3.75 billion last year).

The main imports from the UK also come from the auto sector (they rose from €1.01 billion in 1995 to €2.35 in 2016), closely followed by capital goods. Imports from the UK were 4.1% of the total in 2016, making the country the sixth largest supplier.

As the UK will come out of the EU single market and the Customs Union, another trade arrangement will have to be made. Options range from ‘doing a Norway’ and retaining membership of the European Economic Area, which would allow unfettered access to the single market but would require a large contribution to the EU budget and would not allow the UK to impose restrictions on immigration, to ‘doing a Switzerland’ and negotiating bilateral deals with the EU. But the Swiss have no agreement with the EU on free trade in services, a major area for the UK. An agreement on ‘regulatory equivalence’ regimes for financial services would act much as ‘passporting’ does now. A further option would be to go it alone as a member of the World Trade Organisation.

Direct investment

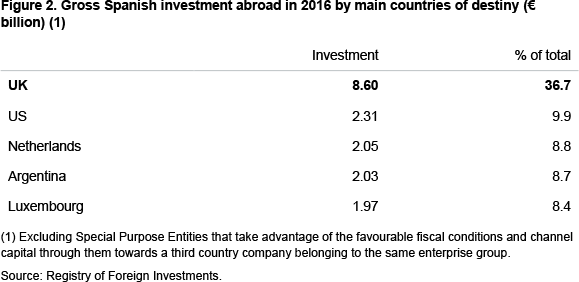

The UK was the preferred destiny of gross Spanish direct investment in 2016, when it totalled €8.60 billion, 36.7% of the total and more than double that in 2015 (see Figure 2).

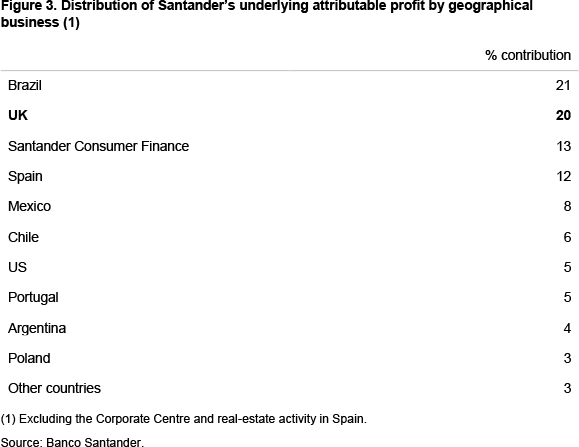

Two Spanish banks are part of the UK banking system. Banco Santander, the euro zone’s largest bank by market capitalisation and one of the global systemically important banks, bought Abbey in 2004, and in 2008 two much smaller banks, Bradford & Bingley and Alliance & Leicester. Its bank in the UK, the third-largest mortgage lender, plays a key role in Santander’s strategy, generating 20% of underlying profit (€1.68 billion) in 2016 (see Figure 3).

The much smaller Banco Sabadell took over TSB and its network of 614 branches in 2015. Sabadell makes around a quarter of its profit in the UK.

The British Bankers’ Association has issued some dire warnings about the Brexit impact on the City of London. Claims have been made that up to 70,000 financial jobs could be lost if after Britain leaves the UK there is no credible relationship in place.

At the moment the so-called ‘passporting’ rights for members of the Single Market allow UK-based banks to offer financial services to companies and individuals across the EU unimpeded.

Santander announced in January that at this point it was ‘totally committed’ to keeping its operations in the UK and did not plan to relocate any of its employees. As part of a global group, Santander UK has more options available to it than its peers when considering how to address the uncertainties over the UK’s exit from the EU.

Santander has revisited the requirements of the Banking Reform Act, which force banks with more than £25 billion of deposits to hive off their consumer-facing business from riskier investment banking activities by 2019. Rather than establish separate retail and corporate banks, it decided last December that customers would be better served at this stage by maintaining its retail, commercial and corporate customers in a strong single structure, with the more complex needs of its largest multinational corporate customers being served by the London branch of Banco Santander.

Santander concluded that the likely disruption from Brexit made the complexity of creating two viable stand-alone banks too difficult and that a wide ring-fence structure was better than the narrow one first envisaged.

Telefónica began operating in Britain in 2006 after buying O2, which operates in the UK, Ireland and Germany, for €26 billion. Telefónica tried to sell O2 in the UK to Hutchison Whampoa in 2015, but the European Commission blocked the sale on the grounds that it would create a monopoly.

The British market is crucial to Iberdrola since it acquired Scottish Power in 2007 for €17.2 billion. Iberdrola has predicted that 25% of its profits in 2010 would come from the UK.

Santander, Telefónica and Iberdrola represent a whopping one-third of the Ibex-35 benchmark index of the Madrid stock market, so if Brexit dented their share prices in a big way the index would feel it intensely.

Infrastructure and construction companies, such as Ferrovial and FCC, also have significant interests in the UK. Ferrovial holds large stakes in four airports –Heathrow, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Southampton– and last year won a €300 million contract to maintain 370km of roads in the East Midlands and a €300 million contract to complete enabling works on the 100km central section of the high-speed rail linking Birmingham and London. FCC Environment (UK) owns a waste-treatment and incineration plant in Buckinghamshire. CAF will supply 281 new vehicles worth €740 million for the next Northern rail franchise.

Hotel chains such as Melia and NH also operate in the UK and last, but not least, Inditex, the world’s biggest fashion retailer, whose flagship store is Zara, has more than 100 stores across the UK including one in Oxford Street, London.

The Brexit impact on foreign direct investment (FDI) will obviously depend, like so much else, on the type of agreement the UK reaches with the EU. By no longer being in the Single Market, the UK would be a less attractive export platform for multinationals as they would bear potentially large costs from tariff and non-tariff barriers when exporting to the rest of the EU. Another factor is that it would be more difficult for multinationals to manage supply chains and co-ordination costs between their headquarters and local branches, and intra-firm staff transfers would be more difficult with tougher migration controls. Lastly, uncertainty over what form trade arrangements will take post-Brexit could dampen FDI.

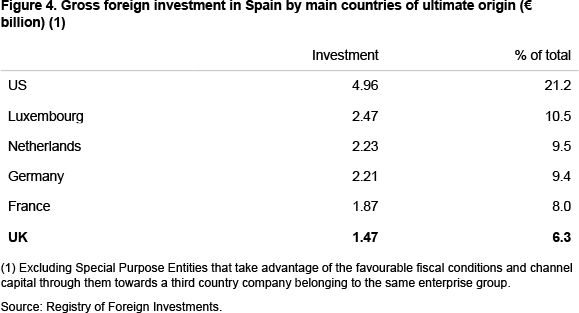

The stock of UK investment in Spain is not as large as Spanish investment in the UK. Gross British investment last year was €1.47 billion, 6.3% of the total. Among the investments was the acquisition by Rolls Royce of the 53% of the Basque company Industria de Turbo Propulsores (ITP) it did not already own.

Brexit gives Spain –and other countries– some opportunities. Madrid is courting London-based companies and banks looking for a home if the UK leaves the EU with a hard Brexit. The National Securities Market Commission (CNMV), the Bank of Spain and the Economy Ministry have set up a task force. The measures on offer to lure companies include fast-track authorisation, the ability to submit all documentation in English and a commitment not to impose regulatory requirements beyond those set down in EU law.

Fisheries

The Spanish fishing fleet is one of if not the biggest in the EU. EU vessels can fish almost anywhere in EU waters, provided they do not exceed strict quotas on the amount they catch. That is set to change for Spain (and other countries) after Brexit, particularly in the North Sea where the country has valuable fishing rights in UK waters.

Citizens

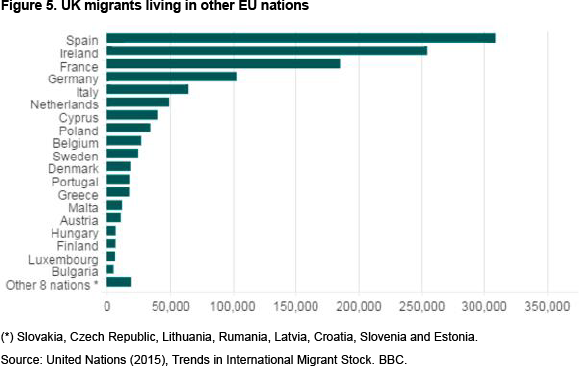

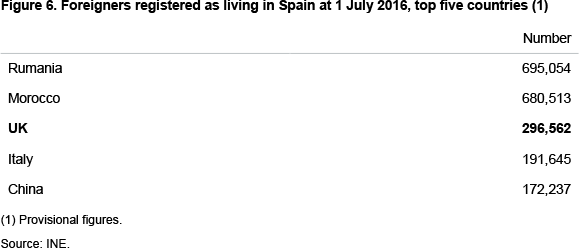

Close to 18 million British tourists came to Spain last year, almost one-quarter of the total, and nearly 300,000 Britons are officially registered as living in the country (76,000 in 1998) at the latest count, the largest group of British ex-pats in Europe and the third largest number in Spain after Rumania and Morocco (see Figures 5 and 6).

The real number of Britons in Spain including those who are not registered and those that have property and spend part of the year in the country is put at 800,000 by the Spanish government. The BBC upped this last month and spoke of a million.

The legacy rights of British citizens in Spain and of Spanish citizens in the UK has become a burning issue. Brexit has generated a great deal of uncertainty and anxiety if not outright anger among Britons in the EU. These people can no longer take for granted that they will be able to continue to live and work unhindered in the country where they decided to establish themselves and carry on travelling freely within the EU.

There is also a lack of a level playing field in holding dual nationality. Britons in Spain need to prove 10 years of residency in their application (five years for Spaniards in the UK) and have to renounce their British citizenship (Spaniards do not have to do the same in the UK). A Briton granted Spanish nationality has to sign a form declaring he has no other nationality, although this has no effect on British citizenship itself. There are no known cases of a passport being subsequently taken away, but with data sharing becoming ever more sophisticated it is harder to keep the second passports secret from the Spanish authorities.

A petition which I helped to launch asking, among other things, for the same right to be granted for long-term UK residents in Spain as a 2015 law that allowed the descendants of Jews expelled from Spain in the 15th century to claim a second Spanish passport has attracted close to 20,000 signatures to date.2

Meanwhile, the number of Britons taking the Spanish citizenship exam, which probes knowledge of Spanish law, history, politics, culture, geography and social customs, and the language test has risen sharply since the UK’s referendum last 23 June. A total of 423 Britons took the test between the referendum and March 2017 compared with only 70 Britons in the six months before the referendum.

British pensioners in Spain, of which there are estimated to be some 100,000 (very few Spanish ones in the UK), are particularly anxious about whether their healthcare will be paid in Spain when Brexit kicks in and that their UK pensions might be frozen.

At the moment, healthcare is covered by reciprocal agreements under the EU’s aegis. Annual increases in the state UK pension, however, are not paid to those living outside the EU.

A trickle of Britons, not wanting to wait two years to see the Brexit terms, assuming there is a deal, have already begun to go home. Some pensioners exist on little more than their basic British state pension of around €550 a month. The number of registered Britons peaked at 397,892 in 2012 and dropped to 296,562 on 1 July 2016.

As well as the healthcare issue, sterling does not go as far in Spain as it did before last June’s referendum. Since then the pound has fallen some 15% against the euro. Some analysts have warned the pound-to-euro exchange rate could fall to 1.0. Sterling’s depreciation did not affect British tourism to Spain last year as most holidays had been booked before the referendum.

The Daily Star went as far as to suggest last month that the ‘aftershocks’ from Brexit ‘could even trigger Spain’s exit from the EU – in a desperate bid to maintain boozy Costa holidays’.

Spain remains predominantly pro-EU –membership is supported across a broad political spectrum– and a Sprexit is definitely not on the cards. All the parties represented in parliament support Spain’s continued EU membership. The country has all the ingredients –massive unemployment, growing inequality, an influx of immigrants and the loss of trust in established political parties– to produce a right-wing populist anti-EU presence in politics, but remarkably has not done so, unlike other countries, most notably France (National Front) and the UK (UKIP).

Among the reasons are: the prevalent and persistent pro-European sentiment, which is higher than average; that Spaniards are the least inclined of any European people to support returning power from the EU to the member states; that they hold favourable attitudes to globalisation compared with other EU countries; and that anti-immigration sentiment is also well below the European average.

Other factors are the relative weakness of Spanish national identity, partly explained by the strong nationalist movements in regions such as Catalonia and the Basque Country, and the association of the extreme right with the 1939-75 Franco dictatorship.

Populism in Spain has gained a foothold in the far-left Podemos, but that party is not calling for Spain to leave the EU.

Britain’s Prime Minister, Theresa May, and her Spanish counterpart, Mariano Rajoy, are in favour of an early and reciprocal deal on citizenship issues, in particular those related to residence, work, benefits, pensions and healthcare. This is not in their hands, however, as it will depend upon the EU’s approach.

‘As regards the rights of EU citizens in the UK and the rights of UK citizens in the EU, Spain is in favour of the amplest respect of these rights in the future but the modalities and conditions will and should be a matter of negotiation’, said Jorge Toledo, the Secretary of State for the EU.

One issue that will have to be resolved is what cut-off date will be used to decide who is eligible to benefit from such a deal.

In the event that there is no global agreement on issues concerning EU nationals in the UK and Britons in Spain, London and Madrid could opt for a bilateral arrangement, but whether Brussels would allow this is yet another unknown at this stage.

Scotland and Catalonia

The UK’s decision to leave the EU has triggered a crisis with Scotland, as it had voted in favour of remaining. As a result, Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s First Minister, is demanding a second referendum on Scottish independence before Brexit kicks in. This needs the permission of Prime Minister Theresa May who has denied it as ‘now is not the time’.

Meanwhile, the Catalan government continues its relentless push for a referendum on secession from Spain, which, unlike the case of Scotland, is unconstitutional. Every move in the direction of a referendum by the Catalan government has been countered by the Constitutional Court.

The Spanish government is a vocal opponent of any kind of separate deal for an independent Scotland, because it would boost Catalonia’s bid for independence and become something of a blueprint for it.

‘Spain supports the territorial integrity of the UK and doesn’t encourage secessions or divisions in any of the member states’, said Foreign Minister Alfonso Dastis. ‘We prefer that things continue the way they are’.

Scotland, he said, ‘would have to join the queue, meet the requirements, go through the well-known negotiations and the outcome will be whatever those negotiations produce’.

The Catalan independence movement is keeping a close eye on Scotland. Some of its supporters claim Catalonia could leave Spain without leaving the EU, something that EU officials have been at great pains to refute.

Once Brexit happens and in the event that Scotland then holds a referendum that voted for independence, would Madrid agree to readmit Scotland into the EU? That question remains to be answered.

Gibraltar

Just as Madrid will not allow any separate deal for Scotland in the Brexit negotiations, so the same approach applies to Gibraltar, which voted 96% in favour of the UK remaining in the EU.

Rajoy has made it clear that the Rock’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU must have the backing of Spain. ‘Gibraltar leaves the European Union when the UK leaves, not because it is part of the UK, but because the UK is responsible for its foreign affairs’, Rajoy said. ‘From then on, all relations between the EU and the UK or those that affect Gibraltar must take into account Spain’s opinion and have its favourable vote’.

Madrid offered Gibraltar co-sovereignty last year as a way for the Rock to continue to be part of the EU, but this was quickly rejected. ‘We have made a very generous co-sovereignty offer, but two can’t dance if one doesn’t want to’, said Dastis, who appears to be rather more pragmatic than his predecessor. ‘And if the UK doesn’t want to negotiate and the population of Gibraltar prefers make its own way outside the union, then that’s up to them. But if they want, in some way, to maintain a relationship with the EU, Spain will make good on its interests’.

The key issue for Gibraltar is not the Single Market, as 90% of business is done with the UK itself, but the border, as it becomes an external one when the UK leaves the EU. Some 7,000 Spanish workers and around 5,000 workers from other countries cross the border every day and without them the Gibraltarian economy, largely based on tourism, financial services and online gambling companies, would suffer and in an extreme scenario could be crippled.

The government of Andalusia, the region where most of these workers live, has voiced its concerns over possible restrictions on crossing the border. The area known as El Campo de Gibraltar, where most Spanish workers who cross the border live, has one of Spain’s highest unemployment rates.

New EU rules requiring tighter checks at Schengen borders will come into force on 7 April and affect Gibraltar. At the moment there is an EU member on either side of it. Currently only citizens from non-EU countries are subjected to stringent checks but once the change kicks in, they will apply to everyone including European citizens. How Spain implements the changes could be a taster of what is in store post-Brexit.

The tussle over Gibraltar poses a threat to a post-Brexit agreement on UK access to the EU’s single aviation market. Madrid has signalled that it might block a deal if it includes the airport of Gibraltar as this would imply recognition of the legal right of the UK to the disputed territory.

The disagreement over Gibraltar airport is already holding up a number of EU aviation laws.

The Gibraltarian economy is forecast to grow by a whopping 7.5% this year. Judging by the investment coming in and booming construction, the existential threat to the economy does not appear to loom as large as it was felt last year, but it is there.

Conclusions

As a result of the magnitude of the Spain-UK relation, Madrid, in particular, has good reason for wanting an amicable Brexit deal and the closest possible post-Brexit relations with London.

William Chislett

Associate Analyst, Elcano Royal Institute | @WilliamChislet3

1 The number of Britons officially registered in Spain at the last count (July 2016) was 296,000. The other 500,000 are assumed to be those who spend part of the year in Spain as they own property in the country. The figure for the number of Spaniards in the UK used by the Office for National Statistics is 130,000.

2 See Dual nationality for Brits who have resided in Spain for more than 10 years.