Original version in Spanish: ¿Qué hay detrás del milagro africano?: implicaciones para la cooperación europea

Theme

The evolution of African economies since the end of the raw-materials boom has been marked by a growing heterogeneity. The EU’s development cooperation should adapt to the new realities unfolding on the continent. Above all, the EU should recognise the specificity of political conditions in each country and act accordingly.

Summary

During the decade of the 2000s, most African economies were able to recover from the deep crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, supported as they were by improvements in domestic policies and more favourable global economic conditions. Despite the gradual movement towards more democratic political environments, improvements in the quality of institutions have not accompanied economic growth; indeed, in some countries dependent on natural resources there has even been a deterioration. After the moderating of primary product prices in 2013, economic trajectories have become differentiated in Africa. While most oil exporters have now entered a crisis, and other countries dependent on natural resources have shown different evolutions, a third group continues to grow at high rates. Nevertheless, with the exception of a small number of ‘developmentalist States’, political conditions on the continent still do not favour growth based on productivity gains.

Europe has traditionally been the external actor with the most significant presence in Africa. As such, Europe has the capacity to help with the continent’s economic transformation. Still, both the importance and the effectiveness of this relationship have eroded with the passing of recent years. Today, European policy towards Africa continues to follow antiquated models and to prioritise European needs over the aspirations of African leaders. Furthermore, European development cooperation continues to be based on the principle that recipient country elites have a sincere interest in development, ignoring the real political incentives actually affecting them. But if it wants to have a positive impact in Africa, the EU should begin to incorporate such variables into their calculus for action. To this end, the EU will need to overcome the incoherence created by the variety of conflicting incentives at the heart of European institutions.

Analysis

The ‘African miracle’: Afro-optimists and Afro-pessimists

The positive change in the trajectory of African economies that occurred during the decade of the 2000s –following on the debacle of the 1980s and 1990s– revived the optimism of the international community with respect to Africa. The stark contrast in the two covers of the Economist –at the beginning and end of the decade– are by now well-known: one from 2000 characterised Africa as ‘The hopeless continent’, but another, from 2011, carried the title, ‘Africa rising’ (a headline which Time Magazine also used again in 2012).

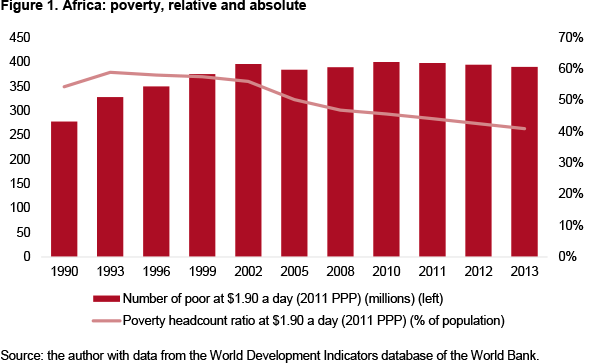

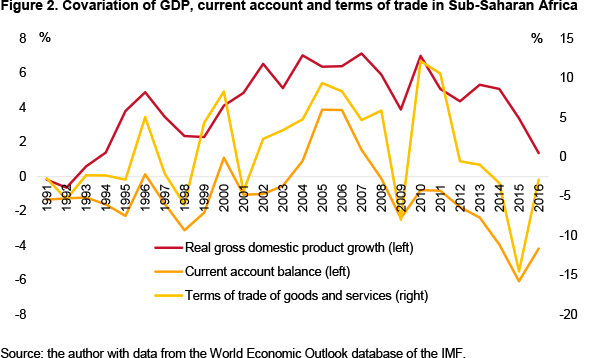

Behind this rising enthusiasm for the region’s potential has been, in fact, an improvement in the principal economic indicators, accompanied by rapid urbanisation and a strong expansion of the internal market. These changes have led to a marked decline in poverty in relative (if not in absolute) terms, due to rapid population growth (Figure 1). In addition, during this period many African governments issued Eurobonds for the first time. These bonds were in high demand, especially amongst European and North American investors.1 Nevertheless, many have continued to argue that Africa’s economic growth was exclusively dependent on the rise of primary product prices generated by the breakneck speed of Chinese growth. In fact, after the collapse of global primary product prices in 2015 and the resulting deterioration in the terms of trade for Africa countries, one can observe a clear deceleration in African growth rates (Figure 2).

If the contribution of primary product demand to the improvement in the economic performance of the Africa continent is undeniable, to attribute growth to this factor alone would simply not be appropriate. African countries benefitted during the 2000s from a series of policies introduced during the two preceding decades in response to the deep economic crisis of the 1980s and 1990s. These policies, largely imposed by the World Bank and the IMF through structural adjustment programmes, focused on correcting economic distortions that supposedly placed a brake on African development. Among these, macroeconomic stability policies stand out, including the ending of the financing of government spending by central banks, important fiscal adjustments and marked improvement in the business environment. These changes coincided with heightened political stability and a reduced number of armed conflicts on the continent. Finally, one should underline the importance of programmes like the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) which, by forgiving the external debt of many African countries, allowed budgets to be freed up for public investment and social spending.

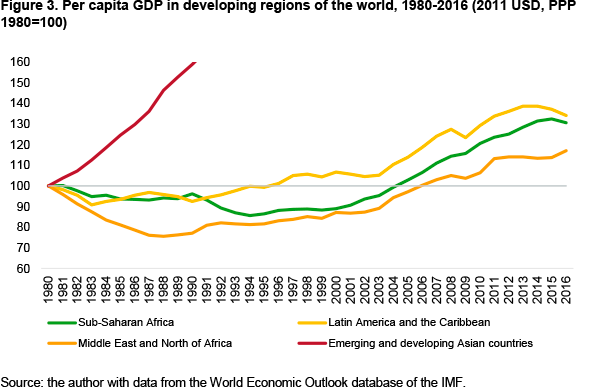

Most of these changes have been maintained up to the present day, protecting against an even more significant deceleration as a consequence of the deteriorating terms of trade. Nevertheless, it is important not to exaggerate the extent of the economic acceleration of the last 15 years. Although it is true that the period from the turn of the millennium has been marked by faster economic growth, in the early years of this period economic growth was barely sufficient to recover the lost ground of the previous two decades. Figure 3 shows how Africa did not regain its 1980 level of real per capita income until 2005. Furthermore, it is important to highlight the doubtful reliability of African macroeconomic data, given the lack of funds dedicated to statistics offices and due to the difficulties inherent in collecting economic data in predominantly informal agricultural economies.2

Institutional framework

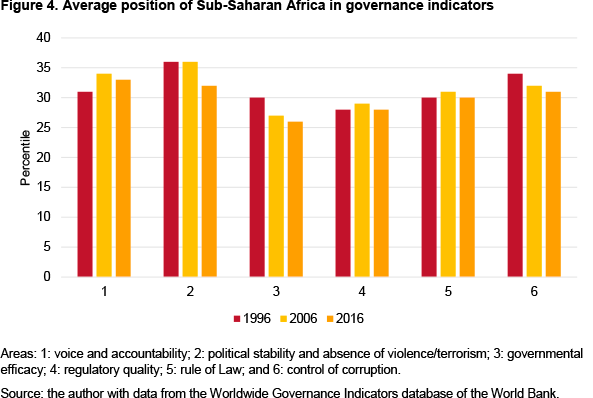

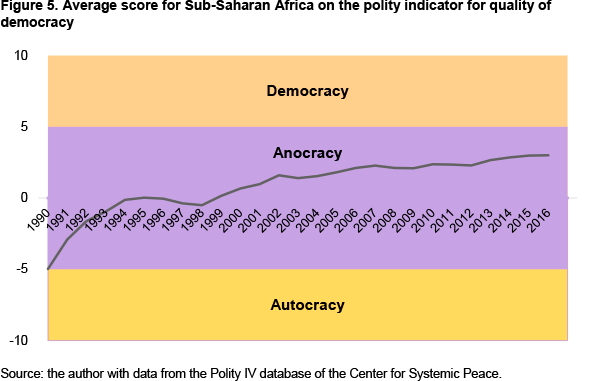

Given the notable economic growth in Africa during the raw materials boom, and the decade of reform and democratisation that preceded it, it would be natural to expect an improvement in Africa’s institutional development indicators. Nevertheless, this is not the picture revealed in Figure 4, from which it becomes clear that most governance indicators have remained stable –or have even deteriorated– over the last 20 years. The only exception has been in the category of voice and accountability, which could be interpreted as an indicator of the extent to which the government responds to the demands of the population. It is interesting to note that, for all the indicators, the 2006 values are higher than for those in 2016, possibly suggesting that institutional quality has also moved in parallel with the fluctuations of primary product prices. Considering that the database is made up of 214 countries, of which 48 are in Sub-Saharan Africa, the position of the region’s average ranking is the 22nd percentile. Figure 4 shows that for the majority of indicators Sub-Saharan Africa is close to the 30th percentile, and at the 26th percentile in terms of governmental efficacy. This implies that the countries of the continent are increasingly bunched at the lower reaches of the ranking.

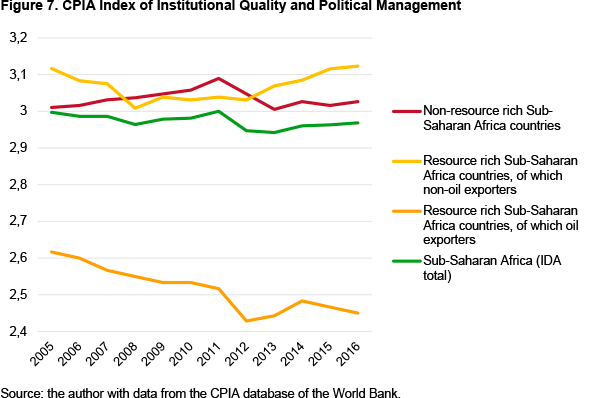

One should analyse this type of indicator with a certain scepticism, given the difficulties in measuring political variables with numerical indicators, their inherent subjectivity and the fact the global indicators on governance measure the relative position of African countries (possibly reflecting simply that some countries have improved less than others). Depending on the indicator, and the institutional variable of interest, we can observe different trajectories. For example, the ‘Polity’ indicator (Figure 5) shows a gradual improvement in the average quality of democracy on the African continent, while according to the CPIA Index of the World Bank, the quality of the public administration and related institutions deteriorated between 2005 and 2016. Therefore, even taking into account the imperfections of numerical indicators for institutional development, the evidence does not allow us to speak of economic growth stimulated by the strengthening of institutions, but rather of growth which has occurred in spite of the persistence of rather weak institutional frameworks.

Differentiating African economies

Beginning in 2013, with the moderation of primary product prices, and specifically since the collapse of the oil price in 2015, the solidity of the ‘African miracle’ has made itself discernible with increasing clarity. The growth of the continental economy fell from 5.1% in 2014 to 3.4% in 2015 and to 1.4% in 2016. The IMF estimates that this year growth will reach 2.6% but, even then, Africa will remain below the global average of 3.6%, as well as below the 4.6% expected in emerging markets and developing countries. The World Bank and the African Development Bank have similar projections. Assuming 2.7% population growth, as foreseen by the UN for 2017, this level of growth would imply stagnation for per capita income. Other economic indicators have followed the same tendency: the current account has deteriorated, currencies have been devalued, risk spreads have increased and the fiscal deficit has grown. Although such negative movements were more accentuated in 2015, with something of a recovery registered in 2016 and 2017, we are still far from the experience of the primary product boom.

Despite the ease with which the African economic miracle appears to have come to an end, the aggregate numbers hide a growing diversity of economic experience across the continent which has been driven primarily by the three most important economies: South Africa, Nigeria and Angola. These economies are by no means representative of the continent taken as a whole: for example, South Africa is the largest African economy, one of the few to have risen to an intermediate income level, and it boasts the continent’s most diversified industrial structure. In recent years, South Africa has been marked by a growth slowdown, high unemployment rates, de-industrialisation, inflationary pressures and eroding balance of payments, along with a persistent legacy of significant inequality left behind by apartheid.

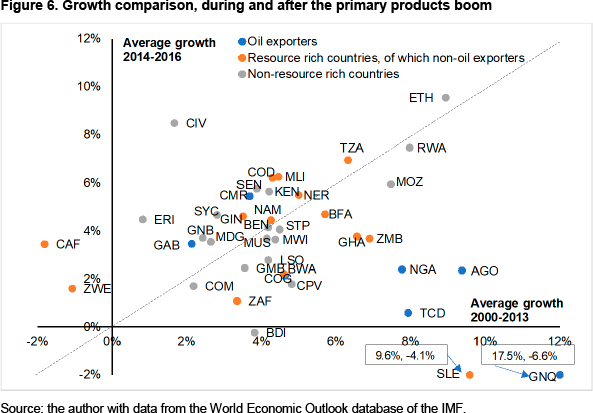

The situation is very different in the other two large African economies. Nigeria and Angola are the major African producers of oil, the product which accounts for nearly all their exports. As a result, they have naturally been negatively affected by the abrupt drop in the price of oil. In both countries, the macroeconomic deterioration has been worse than the African average, particularly with respect to growth (the two economies contracted in 2016), the change in the current account (which until 2013 registered a significant surplus), exchange rate pressures and inflation. In an effort to defend the value of their currencies, these governments imposed controls on foreign exchange markets, which in turn has increased the spread on the black market. Such interventions have been strongly criticised by the international community as negative for local economic activity. Nevertheless, both economies are projected to grow this year, although at lower rates than those observed during the primary products boom.3 The situation is similar among the other African exporters of oil (Figure 6).

The distinction made here between oil exporting countries and the rest of the African economies illustrates the importance of analytically differentiating these economies based on the kind of insertion into the international economy that characterises them. Analyses of the African continent’s economic panorama typically differentiate between oil exporters, other countries dependent on natural resources, and others that are not. Figure 6 presents a comparison of the average growth rates during and after the boom in primary products. The majority of African countries are found bunched together in the centre of the graph, but the oil exporters dominate the lower right quadrant as a result of the sharp fall in their growth rates after the end of the raw materials boom. In the bottom left corner of the graph, one finds the Central African Republic, Zimbabwe and Sierra Leone, all countries which have recently suffered intense internal convulsions. Finally, in the upper righthand section are found those countries which have maintained high economic growth, including Ethiopia, Rwanda and Tanzania, as well as the Ivory Coast, whose growth appears to have accelerated in the wake of the end of its internal conflict. Mozambique also stands out, although its success in the coming years has been put into doubt by the serious scandal generated by the hiding of government debt and by the return of armed conflict.4

Growth models

To better grasp the drivers of recent African growth, to see the region’s medium- and long-term potential, and to discern a possible role for ODA (official development assistance), it is necessary to understand the different ‘growth models’ that exist today in Africa. By ‘model’ we mean a unified vision of economic processes that generate growth in a country. At the same time, an evaluation of the region’s potentials also requires an understanding of the relationship between the economy and the political world. Therefore, we include some political characteristics in our brief panoramic review of the African economic scenario. By abstracting certain characteristics of each country to separate them into groups, we risk ignoring important specificities; nevertheless, in this way it is possible to navigate through a very diversified and varied terrain which is little known in Spain.

The first identifiable development model is that of Nigeria, Angola and the countries of the CEMAC (Central African Economic and Monetary Community), like Gabon, Congo-Brazzaville and Equatorial Guinea: the petroleum exporters. Despite the differences between them, they all have a political economy based on the distribution of petroleum rents. As a result, they are characterised by high levels of corruption, even by African standards, and their governments lack incentives for the diversification of the economy and the provision of public goods.5 In Figure 7 we can see that, in terms of public management and institutional quality, these countries are far from being the worst in Africa, although Gabon and Equatorial Guinea are among the countries with the highest per capita incomes on the continent.

South Africa is an outlier with respect to these development models. At the root of its mediocre economic performance in recent years are structural factors like an education deficit, logistical and infrastructure problems, poor management of public enterprises and large salary increases out of proportion with low productivity. This economic inertia is due in large part to a political equilibrium, or informal pact, in which the corporate leaders of the mining sector, trade union leaders and parts of the government coalition perpetuate a capital-intensive economic model which privileges a minority, without generating much needed employment.6 Indeed, a notable institutional deterioration has been observed recently, with recurring corruption scandals affecting Jacob Zuma’s government and accusations that the State has been ‘captured’ by private interests. Such worrying developments led the credit rating agencies, Fitch and Standard and Poor’s, to downgrade South African sovereign debt in April 2017 to ‘junk’ status.

Beyond the three principal economies and the oil exporters, there are a series of smaller countries together with those with adverse and challenging geographies; there is also another group of larger countries that, despite their potential, suffer from serious problems of political instability. This group is made up either of ‘predator States’ –in which leaders are only concerned with extracting resources from the population for their personal benefit– or of ‘failed States’ –in which there no longer remain any State authority over the national territory–. In such countries, international aid can have very little impact on economic development, and the fundamental challenge is the reestablishment of peace and State authority.7

The most promising economic trajectories in Africa today are found among a group of East and West Africa countries, including Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Ivory Coast, Senegal, Kenya and Mali. The growth of these countries is due to a combination of public investment, external transfers and productivity gains in the agricultural sector; these factors in turn have fostered the growth of the urban services sectors.8 Despite frequent references to the ‘African lions’, this growth model is very different from the Asian model based on the exportation of manufactured goods. This group of rapidly growing countries is projected to continue on this high growth trajectory for a number of years, although there are some doubts as to its sustainability, given that this model is characterised by decreasing returns. At a certain point, the productivity gains stemming from structural change will begin to exhaust themselves, while the productivity of urban sectors will have to grow.

There are some doubts that the politics and institutions of these countries will allow more ambitious economic interventions by their governments. In these (as in most) Africa countries, the fragmentation of political power, the weakness of government structures and the limited productive capacities of companies combine to produce a politics of clientelism, not very propitious for the designing of long-term strategies.9 In addition, in democracies like Ghana and Kenya, the reality of political competition leads to risks of fiscal irresponsibility (especially in Ghana which is subject to an IMF programme). In the other countries of this group there remains a series of political risks, although this is somewhat natural given their low level of development. One recent example has been the controversies over the presidential elections in Kenya.

Among those countries with high rates of growth, Ethiopia and Rwanda are the only exceptions to the general rule with respect to political settlements. Both countries are governed by authoritarian regimes that attempt to rise above internal ethnic divisions and to win legitimacy through economic growth. Their State apparatuses are relatively effective and respond to the developmentalist priorities of their governments, among which an important one worth mentioning is the ambition to strengthen this very State apparatus.10 In addition, their geostrategic importance, their military efficacy and the international perception that Ethiopia and Rwanda are serious about development has given them abundant resources from foreign assistance, which is now equal to 80% of the governmental budget of Rwanda. Nevertheless, despite their success in channelling resources towards improvements in agricultural productivity and extending services to the population, the industrialisation of both countries has been limited to date, and risks stemming from ethnic tensions persist.

This brief analysis of African economic perspectives shows us that, since the end of the primary products boom, the region has been increasingly characterised by its heterogeneity, not only in the economic realm but also in the political sphere, with the co-existence of various forms of government, including more or less consolidated democracies, personalist dictatorships, developmentalist authoritarian governments and failed States. This underlines the need to understand each specific national context and to overcome the tendency to generalise across a continent so vast and so little known in the West. In any case, it is impossible to forget the challenges shared by most African countries, like the need to expand and improve their educational systems and infrastructures, to strengthen the private sector, expand their tax collecting capabilities and to reduce their vulnerability to shocks stemming from climate change in predominantly agricultural economies.

Implications for external action: the role of political economy analysis in ODA

As mentioned, the impact of ODA depends on its interactions within the political context of the recipient country. Frequently, this context is not favourable for investment in projects which stimulate economic growth or provide benefits to the general population. An external intervention, even if well-intentioned, will not be successful if it runs counter to the incentives inherent to the local political circumstances themselves. In these cases, it is possible that aid resources will be used for political ends and will end up benefiting the elites with little interest in economic development. Furthermore, dependence on external resources can aggravate the weakness of African States, given that they reduce the imperative to strengthen State structures to increase their tax collection capacity.11

In recent years, following the example of the British DFID (Department for International Development), the World Bank and some other development aid agencies from northern Europe have begun to integrate political economy analysis into their operations.12 This type of analysis can be used for many purposes, including the formulation of strategic visions and the identification of obstacles to project implementation. Political economy analysis can also serve as a starting point for a more dynamic vision which proposes long-term political, economic and social change. Given the interdependence between politics and economics, such a vision should be based on a recognition that each country will follow a unique, distinct development path, even if it attempts to identify common patterns between the trajectories of different countries.13

Despite the potential for political economy analysis to promote a more effective development agenda, it has been difficult to institutionalise, due to current bureaucratic incentives in development aid agencies. In addition, it is natural that the Heads of State of recipient countries do not like the idea of external actors interfering with local political balances and settlements. Neither does this type of interference help foreign countries seeking to expand their political, diplomatic and economic presence on the African continent. Therefore, in the next section we analyse in more detail the challenges facing the implementation of a more effective development aid framework within European institutions.

The EU-Africa relationship

As a consequence of former colonial ties, Europe has a strong presence in Africa. For the EU (and its predecessors), the central component of relations with Africa since 1975 have been the institutions of the ACP (Africa, Caribbean and Pacific) States, which group together African countries with small developing island States. Originally, the complex of institutions which brought the ACP together with the EU had important functions in trade, development aid and political cooperation. Nevertheless, the importance and effectiveness of this relationship have suffered over the course of the years due to changes in global geopolitics, the growing regionalisation of international relations, excessive heterogeneity among the countries of the ACP and EU expansion.14 The Cotonou Agreement of 2000 was supposed to correct for some of these problems and adapt the relationship to the 21st century, but it has not been that successful, particularly with respect to the polemic surrounding the ratification of the EPA (Economic Partnership Agreements). Therefore, the debate has begun over whether, at the conclusion of the Cotonou Agreement in 2020, it will even be possible to maintain the current form of ACP-EU cooperation.

At the same time, the direct relationship between the EU and the African Union (AU) has gained in prominence since the release of the Joint Africa-EU Strategy (JAES) in 2007. The EU has also pushed other initiatives, like the Emergency Trust Fund, the Africa Investment Facility, the Foreign Investment Plan, and a series of sub-regional accords. The multiplicity of modalities in EU-Africa relations produces a complex and at times incoherent architecture, where elements of realpolitik mix with development aid. Such incoherence stems from the variation in institutional incentives faced by the different internal organs of the EU.15 To this confusion are added the divergent interests of the Member States, especially between the ex-colonial powers and the rest of the European countries.

Problems in the framework of EU-Africa relations create important obstacles for the promotion and institutionalisation of a more pragmatic development cooperation policy which is conscious of the real challenges in the recipient countries. In spite of the evidence that the current form of development cooperation has produced few concrete results, European leaders continue to give priority to formal summits where declarations of good intentions abound to the detriment of more concrete actions to create favourable political conditions for development.16 One recent example has been the German idea to create a ‘Marshall Plan for Africa’,17 ignoring the evidence which suggests that it is unlikely that a simple injection of money will be capable of catalysing development on the continent (on the contrary, it would only accentuate the dependence of African elites on external resources and reduce further their incentives to transform the economy). Such initiatives respond to the imperatives of the media and of power; they are not evidence of any serious attempt to understand the challenges of development. Often such projects only express the preoccupations of European countries with the issues of democracy and human rights, and, contrary to the intentions expressed at the various summits, they do not consider the primarily economic concerns of the African countries. As a result, a lack of confidence exists between the two sides, the lines of dialogue have withered, and space has opened up for actors in the Global South like China (which gives a more central role to self-determination in its Africa policy).

Conclusions

To increase the effectiveness of its development cooperation with Africa, it is essential that the EU recognise the growing heterogeneity of the continent and adapt its policies to the newly emerging realities. These policies should be more realistic and recognize the interests at stake. It is especially important to abandon an agenda which imposes European normative ideals in contexts where the informal institutions do not support them, and to think of long-term strategies for achieving these ideals. The EU has a fundamental role to play. Nevertheless, the importance and effectiveness of Europe’s relationship with Africa has eroded over the years, even if it remains the external actor with the largest presence on the continent and its principal donor of international development cooperation assistance.

The African continent faces many challenges, but from the perspective of economic growth, the priorities vary, depending on the growth model and the political regime. For example, in oil exporting countries, the principal challenges are good management of petroleum income and the diversification of the economy. In fragile States (or those in conflict) the key objective is the reestablishment of viable States. In the States with clientelist politics –the modal case in Sub-Saharan Africa– it could be that the most promising interventions are those which establish ‘islands of excellence’ whether in terms of specific industries or more efficacious bureaucratic entities. Finally, the traditional frameworks of cooperation would be more successful in the so-called ‘developmentalist States’. In these States there is a real interest on the part of governments to expand the supply of public services, and it is likely that efforts to improve economic competitiveness will be received well by such governments, as long as they do no reduce their control on power. These are examples of the types of considerations that development cooperation policy should make, but it is clear that political economy analysis of cooperation should be based on a more complex theoretical framing.18

To improve the quality of European cooperation it will be necessary to overcome the collective action problems inherent in a complex and fragmented institution like the EU and to create an institutional architecture that allows a more realistic analysis of development. Currently, the political and institutional incentives are not propitious for such innovations, and it seems unlikely that this situation will radically change in the short to middle term.19 Nevertheless, the absence of incentives does not imply the impossibility of change; in such cases, it is necessary for ‘political entrepreneurs’20 to take the initiative to reform institutions. In Europe, the UK, the Netherlands and the Nordic countries have already reformed their development cooperation policies to be more consistent with the complexities of the development process. If Spain wishes to truly become a policy ‘maker’ –rather than continue to be a mere policy ‘taker’– this would be an agenda to which it could commit, in coalition with other reformist actors.

Nicolás Lippolis

Researcher, Centre for the Study of African Economies, Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University | @nicolaslippolis

1 John Mbu (2016), ‘Why Eurobonds are an important source of finance for Africa’, World Economic Forum, 12/II/2016.

2 Morten Jerven (2013), Poor Numbers, Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

3 The IMF projects that in 2017 Nigeria will grow 0.8% and Angola 1.5%. At the same time the World Bank projects that both economies will grow by 1.2%.

4 Joseph Cotterill (2017), “State loans at heart of Mozambique debt scandal”, Financial Times, 25/VI/2017.

5 For a classic analysis of the political effects of petroleum, see Terry Lynn Karl (1997), The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States, University of California Press, Berkeley. The African case is also well-illustrated by Ricardo Soares de Oliveira (2007), Oil and Politics in the Gulf of Guinea, Hurst, London.

6 See the analysis of Haroon Bhorat, Aalia Cassim & Alan Hirsch (2014), ‘Policy co-ordination and growth traps in a middle-income country setting: the case of South Africa’, UNU-Wider Working Paper, nr 2014/155.

7 The reconstruction of States after conflicts is another fertile field within the debate on international cooperation, but here we are more interested in cooperation aid in the economic field.

8 Xenshin Diao, Margaret McMillan & Dani Rodrik (2017), ‘The recent growth boom in developing countries: a structural change perspective’, NBER Working Paper, nr 23132.

9 For an analysis of the role of ‘political equilibria’ (political settlements) in African industrial politics, see Lindsay Whitfield, Ole Therkildsen, Lars Buur & Anne Mette Kjaer (2015), The Politics of African Industrial Policy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

10 Will Jones, Ricardo Soares de Oliveira & Harry Verhoeven (2013), ‘Africa’s Illiberal State-builders’, Oxford Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper Series, nr 89.

11 See Todd Moss, Gunilla Pettersson Gilander & Nicolas Van de Walle (2006), ‘An aid-institutions paradox? A review essay on aid dependency and State building in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Center for Global Development Working Paper, nr 74.

12 For the story of World Bank experience in the application of political analysis to aid programmes, see Verena Fritz, Brian Levy & Rachel Ort (Eds.) (2014), Problem-Driven Political Economy Analysis: The World Bank’s Experience, World Bank, Washington DC.

13 For an example of this type of study, see Brian Levy (2014), Working with the Grain: Integrating Governance and Growth in Development Strategies, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

14 See the analysis of the European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECPDM) ‘ACP-EU relations beyond 2020: engaging the future or perpetuating the past?’ and ‘The future of ACP-EU relations: a political economy analysis’.

15 See, for example, Maurizio Carbone (2011), ‘The European Union and China’s rise in Africa: competing visions, external coherence and trilateral cooperation’, Journal of Contemporary African Studies, vol. 29, nr 2.

16 For a more profound analysis of this issue, see Jean Bossuyt (2017), ‘Can EU-Africa relations be deepened? A perspective on power relations, interests and incentives’, ECDPM Briefing Note, nr 97.

17 For more details, see Germany’s ‘Marshall Plan with Africa’, Devex, and the cooperation agreement between the G20 and Africa presented at the last G20 Summit.

18 For studies on external cooperation with coverage of political interests, see Pablo Yanguas (2014), ‘Leader, protester, enabler, spoiler: aid strategies and donor politics in institutional assistance’, Development Policy Review, vol. 32, nr 3, p. 299-312; and Pablo Yanguas (2016), ‘The role and responsibility of foreign aid in recipient political settlements’, ESID Working Paper, nr 56.

19 For a fuller analysis of EU-African relations see Maurizio Carbone (Ed.) (2013), The European Union in Africa: Incoherent policies, asymmetric partnership, declining relevance?, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

20 Dani Rodrik (2013), ‘The Tyranny of Political Economy’, Project Syndicate.