| This Policy Paper is a contribution to the project “Think Global – Act European (TGAE). Thinking strategically about the EU’s external action” directed by Notre Europe – Jacques Delors Institute and involving 16 European think tanks: Carnegie Europe, CCEIA, CER, CEPS, demosEUROPA, ECFR, EGMONT, EPC, Real Instituto Elcano, Eliamep, Europeum, FRIDE, IAI, Notre Europe – Jacques Delors Institute, SIEPS, SWP.The final report presenting the key recommendations of the think tanks will be published in March 2013, under the direction of Elvire Fabry, Notre Europe – Jacques Delors Institute, Paris. |

Summary

Since the introduction of the euro in 1999, the external representation of the eurozone has been incrementally developed, but no formal amendments have been made. This Policy Paper discusses the case for a consolidated representation of the eurozone in international economic fora, analyses the obstacles to achieving it, and puts forward proposals to solve some of the existing obstacles. It argues that there is a strong case for creating a single voice for the euro in the world in general and in the IMF in particular, especially after the global financial crisis and the emergence of the G20 as the main forum for global economic governance. However, some eurozone countries are unwilling to give up sovereignty and transfer more power to Brussels. In addition, the functioning of the IMF, which is based on high majority voting, may induce major eurozone countries not to give up their individual influence over IMF decisions. Nevertheless, the recently created European Stability Mechanism could act as a catalyst for solving some of these problems.

Introduction

Since the introduction of the euro in 1999, the external representation of the eurozone has been incrementally developed, but no formal amendments have been made. The Maastricht Treaty sketched the general framework, but key questions on the representation of the eurozone in international economic organisations and its relationships with major strategic partners were left open. While the European Central Bank (ECB) represents the eurozone in monetary affairs, external representation with regard to macroeconomic and financial matters remains fragmented between the Member States and the European Commission. The Treaty of Nice (2001) and the Treaty of Lisbon (2009) left the provisions for the external representation of the eurozone unchanged. Article 138 of the TFEU[1] maintains the legal base for a consolidation of the eurozone’s external representation that has existed since its launch. This suggests that, although the currency union was primarily created for internal reasons, the EU’s architects also had in mind that the single currency could become an important instrument in the Union’s foreign economic policy.

This Policy Paper discusses the case for a consolidated representation of the eurozone in international economic fora and analyses the obstacles on the way there. After a brief description of the changing global economic environment, it examines the potential benefits of establishing a single voice for the euro in the international arena and its main obstacles. The conclusion presents some specific proposals.

1. A changing global environment

Two recent changes in global economic and financial governance have emphasised the decline of European power in global economic and financial governance. In 2009, the G20 summit was launched to discuss the sources and consequences of the global crisis and potential international coordination efforts. In comparison to the previous top economic and financial summits, the G7 and later the G8, the EU’s (just like the US’s) relative weight is far inferior. In the G8, four out of eight members, or 50%, were European. In the G20, they number four out of 20 and hence only 20% of the membership. Moreover, the EU’s presence in the IMF has been relatively reduced. According to the decision of October 2010, European governments had to give up two of their eight seats on the Executive Board. In both reform events, the growing economic weight of new players on the global scene was a root cause for the change. The recent crisis has accelerated the loss of relative economic weight and weakened the EU politically, as several Member States have become recipient countries of IMF aid, accelerating the decline of Europe’s normative power.

As the debt crisis has unfolded in the eurozone, the discussion about a common representation in key international organisations with direct powers on global financial flows and the economy, such as the IMF, has intensified. The goal is to improve coordination and influence over decisions affecting the eurozone as a whole, or, single Member States. For instance, IMF programmes currently run in three eurozone Member States: Greece, Portugal and Ireland, with the application of conditions that affect national policies. The unification of eurozone Member States’ representation within international organisations can have strong economic, legal and political implications, in particular in terms of internal redistribution of powers among eurozone Member States. However, as we will see below, some key players to date remain sceptical.

2. The eurozone in the IMF

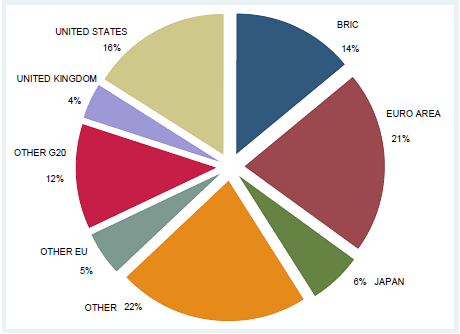

Only three eurozone members are top 10 IMF countries and none of them are the top three (according to their voting share). The US has the biggest quota and voting share, resulting in a single concentrated power, able to influence the entire activity of the Fund. A different balance of powers would emerge if the voting shares of eurozone countries were combined. The sum of their voting shares is roughly 21% of the IMF total quotas (see Figure 1 below), well above the US (around 16%). Some coordination among eurozone members does already take place, but it rarely results in effective representation of the eurozone.

Figure 1: Overall eurozone voting share in the IMF compared to other members

Note: after full implementation of 2010 quota reform.

3. Obstacles to unifying eurozone external representation

There are essentially two reasons why governments are hesitant to opt for unified representation. Internal distrust among Member States emerges due to the absence of common rules on the political governance of the eurozone, emphasised by the absence of common democratic institutions able to take this role and coordinate the common seat. Member States do not want to lose political control over their foreign and economic policies. The second factor that contributes to political distrust in a common representation is an exogenous one: the governance of the IMF. In effect, the organisation’s voting system mainly relies on high majority voting (mostly 70% and 85%). As a result, every decision would require a consensus among all major countries. Due to its fragmentation in eight single memberships and 16 coalitions (188 members), a relatively medium-size country may also influence the outcome of a decision; in effect, decisions are rarely taken without consensus. By holding the power to stop important initiatives, a country may not be interested in merging quotas simply because doing so may only reduce its control over the organisation’s decision-making process. Therefore, this voting structure may persuade major eurozone countries not to give up their individual influence over IMF decisions. Moreover, some countries argue that the eurozone is actually more powerful with the status quo because eurozone countries are over-represented on the Executive Board. In order to maximise influence, they must simply coordinate their positions.

Besides IMF decisions, on which eurozone countries mostly vote together in the end, there are more conflicting issues. For instance, EU Member States do not have a common position in debates about the international monetary system, the euro’s role as a reserve currency or global macroeconomic imbalances. Coordination is hence more difficult. Important tensions exist, for instance, between France and Germany. While the former prefers a lower exchange rate for the single currency, to promote exports, and ultimately wants the euro to challenge the dollar’s hegemony, the latter sees exchange rate developments not as a matter of political choice but a result of competitiveness. It generally favours a strong currency to help control inflation and sees less benefits in the euro’s internationalisation (international currencies tend to have more volatile exchange rates and their central banks can be forced act as international lenders of last resort in situations of panic).

In sum, there are domestic political aspects and external factors that complicate the assessment of benefits and costs of a unified representation. However, digging more into the details, this initial analysis may prove wrong for two reasons. We will explore these in the following section.

4. Arguments for consolidated representation

Firstly, the concentration of quotas among eurozone Member States would increase the direct quotas of control and officially harmonise the actions of these countries at the IMF, thus reducing coordination problems that may clash with the need to support eurozone-wide decisions.[2] Second, the merging of quotas would reduce the total number of coalitions. Fewer coalitions means the possibility of exercising more influence over other coalitions or attracting a high number of satellite countries into a coalition led by the eurozone – countries which are already in different coalitions with individual eurozone countries. A merged quota would then provide fertile ground for new initiatives and formal power to block any decision without eurozone approval.

There are also more general reasons that would justify a common seat at IMF level. Firstly, common representation in international organisations would promote greater internal coordination on political governance of the whole region (EU). Secondly, it may stimulate international cooperation (e.g. trade agreements) which would benefit the whole region, because it reduces coordination issues and provides one access point for non-eurozone countries. Thirdly, it makes representation at the global level more effective in terms of cumulative votes that can be exercised in the decision-making process. Fourthly, common representation in international financial organisations can provide a springboard for developing coordination in other important areas such as foreign policy.

A decline in economic weight, diminishing financial resources and the loss of normative power will weaken the EU’s capacity to influence global governance and regulatory efforts. Europe will only be able to secure its place among the major players if it combines a sound economic base with an effective representation of its interests on a global scale. It will also have to retain stable alliances, in particular with the US, which itself wants the EU to improve the coherence of its external representation.

If all this is not followed through and if internal divergences grow further and increase political tensions, the eurozone is likely to sell itself short. From a macroeconomic perspective, it is technically one economy as long as the single currency and the single market exist. But it will only be perceived and treated as such if it manages to overcome internal economic and political tensions and translate internal economic unity into unified external political representation. Recent economic trends increase the pressure on European governments to pool their strength and both informally and formally improve the external representation of the EU in international economic and financial fora.

5. The internal dimension of external representation

As a result of the current crisis, the EU has started reforming its internal economic governance mechanisms. A so far unexplored question is the extent to which internal governance reform holds consequences or opens up opportunities for a better external representation of interests.

Sketched in very broad terms, the EU’s reaction to the financial and economic crisis has created a new impetus in five policy areas. First, EU financial market regulation is undergoing changes, with more supervisory power for the eurozone and an attempt to create a single rule book. Second, budgetary policy coordination is being further strengthened with tougher rules and quicker sanctions at the European level, while national fiscal policy should underpin the jointly agreed objectives. Third, a new mechanism for macro-economic policy coordination has been introduced, including the “Euro Plus Pact”, a top-level attempt to get binding commitments from eurozone heads of state and government to an annually-defined reform catalogue intended to help improve European competitiveness and prevent persistent current account imbalances within the eurozone. Lastly, the eurozone has equipped itself with a new permanent crisis resolution mechanism (the European Stability Mechanism (ESM)) to facilitate a joint intervention with the IMF in the event of a sovereign debt crises in the eurozone.

An increased degree of internal policy coordination may, in the long run, harmonise economic developments and policy preferences to a certain extent. This could mean that Member State positions on global economic and finance issues are at least partially aligned. Recently, however, internal divergences have actually translated into contradictory positions on global governance issues.

Macroeconomic imbalances between eurozone Member States are, for example, a pressing issue to tackle within the currency union, just as they are at the global level.[3] Over the past few years, for instance, China, Germany and oil and gas exporting countries in the Middle East have accumulated large trade surpluses while the US has experienced growing deficits. Such systemic macroeconomic imbalances can cause a misallocation of capital and financial bubbles, as they did in the eurozone. This danger was revealed by the recent crisis, when large capital flows into the U.S. drove down the cost of loans and thus contributed to the bubble in the housing sector.[4] There is hence a need, both at the European and global level, to promote policy changes which address domestic and international distortions that are a key cause of imbalances.

While the current account of the European Union is more or less balanced, several EU member countries run large surpluses or deficits. Aside from creating differences between EU representatives in the G20 debates, it also hinders European governments from effectively leading negotiations to set up macroeconomic surveillance and coordination procedures in the EU.

In the G20, there seems to be agreement that the deficit countries cannot resolve their imbalances alone. The partners differ, however, on how to reduce global macroeconomic imbalances. In Pittsburgh, leaders agreed on a new “Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth” under which they would review each other’s national economic policies, supervised by the IMF. Numerical targets as well as enforcement mechanisms, such as penalties or sanctions, were left out of the agreement.[5] The two largest Member States of the EU, France and Germany, disagreed over the proposal to include targets and sanctions. Paris first warmly greeted the idea of defining a limit for trade imbalances to GDP,[6] which appeared in the debate before the Seoul summit. Meanwhile, Germany, shoulder-to-shoulder with China, wiped this idea off the table. The EU has managed to formulate a joint position. At the G20 summit in Seoul in late 2010, leaders agreed to work on indicators to measure the sustainability of imbalances. In February 2011, G20 ministers developed a set of indicators in order to focus on persistently large imbalances require policy actions. A goal has been set to establish indicative guidelines by the next meeting in April, against which each of these indicators will be assessed.[7] Such progress on the question of how to fight imbalances, however, does not eliminate the divergent views that exist concerning why imbalances should be fought at all.

6. How to move forward

As we have seen, there is a strong case for creating a single voice for the euro in the world, but some eurozone countries are unwilling to give up sovereignty and transfer more power to Brussels.

Increasing coordination among Member States for the representation of the eurozone within international organisations such as the IMF may be potentially pursued through two sets of actions.

The first option may not require any major institutional reform at the EU or IMF level; basically, it would improve coordination in the use of voting rights currently allocated to eurozone members and split into two individual memberships and six different coalitions (with very limited coordination at EU level). It can be implemented in the form of a eurozone committee, established within the current EU institutional framework (preferably the Eurogroup)[8], which would coordinate the set of voting rights within the IMF and perhaps change the current set of coalitions into one or few. Memorandums of Understanding among Member States may need to be drafted to make sure that a clear set of rules is defined ex ante on how votes should be exercised. This option, in practice, would not require any IMF reform, but it would require strong political support within the eurozone and perhaps the reshuffle of the current six coalitions within the IMF Executive Board.

The second option would involve the creation of a single membership for eurozone countries. Membership would need to be officially handled by an institution that has control over budget and fiscal policies, since the voting rights are immediately linked to the effective quota held within the Fund. This institution could be represented by the European Stability Mechanism, which may increase its role in future economic governance in the eurozone if it becomes central in the coordination of fiscal policies. An alternative would be a eurozone economic government, if the EU embarks on a major treaty change. Regardless of which institution becomes central, this option may face two significant impediments. First, it requires a reform or at least a reinterpretation of IMF Articles of Agreement, since officially only “countries” can be part of the IMF. A clear, international-level agreement would be needed to determine whether these countries can be federated into one institution representing them. The second impediment to such a proposal concerns the re-calculation of the formula. By removing intra-EU flows from the calculation of the quota, the eurozone total quota may fall well below 21%, making the first option more attractive if no major reform of the formula is planned in the coming years.[9] However, this option would make more sense (for the benefit of having an integrated framework of external representation) if the IMF modifies this formula and reduce the weight of eurozone countries that are currently overrepresented.

Daniela Schwarzer, Head of Research Division EU Integration, SWP.

Federico Steinberg, Senior Analyst for International Economics, Elcano Royal Institute.

Diego Valiante, Reserch Fellow, CEPS.

[1] Article 138.1 states that “In order to secure the euro’s place in the international monetary system, the Council, on a proposal from the Commission, shall adopt a decision establishing common positions on matters of particular interest for economic and monetary union within the competent international financial institutions and conferences”.

[2] Differences of interest will remain among Member States, for instance dealing with global imbalances or certain aspects of the financial regulation debate in the G20 context, but the eurozone will be forced to achieve a common position.

[3] Olivier J. Blanchard and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, “Global Imbalances: In Midstream?”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP7693, 2010.

[4] Eric Helleiner, “Understanding the 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis: Lessons for Scholars of International Political Economy,” in: Annual Review of Political Science, 14, 2011, p. 67-87 (here: 77).

[5] “G20 Leaders Statement: The Pittsburgh Summit”, 24-25 September 2009.

[6] “G20: EU Split over US Offensive against Global Imbalances”, European Information Service, 25 October 2010.

[7] “Communiqué”, Meeting of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, Paris 18-19 February 2011.

[8] See Alessandro Giovannini and Diego Valiante, “Unifying eurozone representation at the IMF: a two-step proposal”, Working Paper, 2013, forthcoming ECPR.

[9] Ibid.