Theme

This paper analyses the scope and quality of Tokyo’s ‘Quality Infrastructure’ development policies and initiatives in East and South-East Asia and the expansion of Japanese security and relations with the US, India and Australia. All of this, as Tokyo explains, in the context of Japan’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) policy in and towards the region.

Summary

Tokyo’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) is the core of Tokyo’s strategy and policies in and towards the Indo-Pacific. The FOIP is fairly obviously designed as a competitor to Beijing’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI), enabling Tokyo to regain some of the economic and political clout lost over the countries in East and South-East Asia since Beijing announced the BRI in 2013. The main goal of Japan’s FOIP is to promote what is referred to as ‘connectivity’ between Asia, the Middle East and Africa. ‘Connectivity’ stands for, above all, the expansion of trade and investment ties helped by improved infrastructure links. At the core of Japan’s FOIP is what Tokyo calls ‘Quality Infrastructure’, ie, infrastructure development projects funded or co-funded by Japan in Asia and Africa. Tokyo’s FOIP is complemented by the so-called ‘Quadrilateral Security Dialogue’ (Quad), an Indo-Pacific security forum facilitating dialogue and consultation between Japan, Australia, India and the US. What Japan is doing in terms of ‘Quality Infrastructure’ and expansion of bilateral (with India) and multilateral (with India, the US and Australia) security and defence ties is examined in this paper.

Analysis

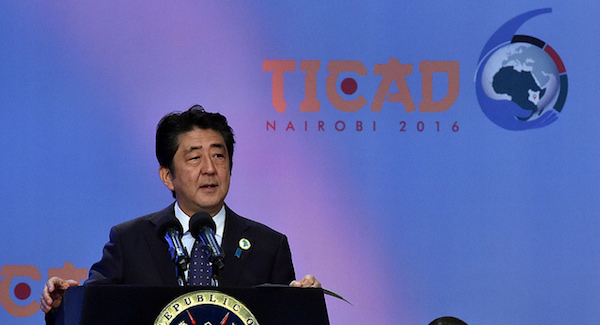

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe formally introduced the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) strategy on occasion of the Fourth International Conference on African Development (TICAD VI), held in Nairobi in August 2016. Since then, the FOIP concept has taken shape and has become a strategy into which Tokyo is investing enormous resources and capital. The ‘Quadrilateral Security Dialogue’ (Quad) complements the FOIP and is aimed at further enhancing Japanese-Indian-Australian-US cooperation in the areas of maritime security, terrorism and freedom of navigation. Japan’s approach to maritime security translates, among other things, into the Japanese navy and coastguard, together with counterparts from the US, India, and Australia, contributing to US-led ‘freedom of navigation operations’ (FONOPs) and joint military exercises in the South China Sea. In August 2018, for instance, Tokyo deployed three warships to the South China Sea to hold joint military exercises with five Asian navies and the US from the end of August to October. At the time, Japanese navy vessels made calls in ports in India, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines and linked up during the exercise with the US Navy deployed in the region.1 Furthermore, Tokyo announced it would strengthen Sri Lanka’s maritime security capabilities by donating two coastguard patrol craft.2 In September 2018 a Japanese submarine joined for the first time a naval military exercise in the South China Sea in disputed territorial waters (claimed above all by China). At the time, a Japanese submarine was accompanied by other Japanese warships, including the Kaga helicopter carrier.3

‘Quality Infrastructure’

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that developing Asia needs around US$26 trillion in infrastructure investments from 2016 to 2030.4 Japan has decided to make a significant contribution. In May 2015 Prime Minister Abe announced a ‘Partnership for Quality Infrastructure’, initially providing US$110 billion for financing the construction of roads, railways and ports in Asia.5 Tokyo’s ‘Quality Infrastructure’ is, at least on paper, fundamentally different from how China under its BRI scheme is financing or co-financing infrastructure projects in Asia and Africa. Chinese infrastructure development policies, be it within or outside the BRI framework, are (very) often criticised for lacking transparency and being non-sustainable and exclusive; exclusive in the sense that Chinese companies build infrastructure on a sole-source basis to claim privileged access to the infrastructure they finance and build. Furthermore, many recipients of Chinese funds fear getting caught in so-called ‘debt traps’: China is giving out loans to countries aware that they will never be able to repay them, in turn creating a political dependency that enables Beijing in certain cases to ask for territorial concessions and control over the facilities Chinese SOEs are investing in. Such was the case of the investments of the China Harbor Engineering Company, one of Beijing’s largest state-owned enterprises, in the Hambantota Port Development Project. When in late 2017 the Sri Lankan government found itself unable to service the debt it owed its Chinese investors it agreed to hand over control of the port together with 15,000 acres of land around the port in a 99-year lease. While the deal with China erased roughly US$1 billion in debt for the port project, Sri Lanka today has more debt with China than before, as other loans have continued with rates significantly higher than from other international lenders. In total, Sri Lanka owes more than US$8 billion to state-controlled Chinese firms.6 In March 2018 the Centre for Global Development published a study naming eight countries at high risk of debt distress related to BRI-related lending, including Laos, Kyrgyzstan, Maldives, Montenegro, Djibouti, Tajikistan, Mongolia and Pakistan.7

On occasion of the G7 summit in Japan in 2016, Tokyo announced the five principles guiding its ‘Quality Infrastructure’ projects: (1) effective governance and economic efficiency in view of life-cycle costs as well as safety and resilience against natural disasters, terrorism and cyber-attack risks; (2) job creation, capacity building and the transfer of expertise and know-how for local communities; (3) addressing social and environmental impacts; (4) alignment with economic and development strategies including aspects of climate change and the environment at the national and regional levels; and (5) effective resource mobilisation including through PPP.8 In 2016 Tokyo expanded the ‘Partnership for Quality Infrastructure’ initiative to US$200 billion by including Africa and the South Pacific. Envisioned and ongoing Japanese investments include: (1) US$320 million for the construction of a port in Nacala, Mozambique; (2) US$300 million for port and related infrastructure in Mombasa, Kenya; (3) US$400 million for a port in Toamasina, Madagascar; (4) US$2.2 billion for a trans-harbour link in Mumbai, India; (5) US$3.7 billion for a port and power station in Matarbari, Bangladesh; (6) US$200 million for a container terminal in Yangon, Myanmar; and (7) US$800 million for a port and special economic zone in Dawei, Myanmar.

Other Japanese ‘Quality Infrastructure’ projects include:

- The Mombasa container port development project in Kenya. In 2017 the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)9 signed a US$340 million loan agreement with the Kenyan government for the construction of a second container terminal.

- The Mumbai-Ahmedabad high-speed rail corridor.10 Japan is funding 80% of the bullet-train11 project through a soft loan of roughly US$8 billion at an interest rate of 0.1%, with a tenure stretching over 50 years.

- The Thilawa Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Myanmar/Burma. In August 2017 the JICA signed a loan agreement with the Myanmar Japan Thilawa Development Ltd.12

- A US$300 million gas-fired power station in Tanzania. The project covers Japanese assistance to construct a gas-fired power station in Tanzania that will increase the country’s generating capacity by 15%. The work is conducted by a number of Japanese companies and contractors such as Sumitomo Corporation, Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems and Toshiba Plant Systems and Services.

In South-East Asia, Tokyo is funding roads and highways in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam and is assisting in the development of Cambodia’s Sihanoukville port and the construction of railway lines in Thailand. In 2016 Tokyo launched the ‘Japan-Mekong Connectivity Initiative’, which funds the trade-promoting East-West Economic Corridor from the port of Danang in Vietnam through Laos and Thailand and on to Myanmar. Japan is also financing the Southern Economic Corridor that is envisioned to run from Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam through Cambodia and southern Laos to Thailand and the south-eastern Myanmar port city of Dawei. In October 2018 Tokyo provided US$625 million for projects aimed at reducing traffic congestion and improving drainage and sewerage systems in the Burmese capital Yangon.13 Also in 2018, the US and Australia officially endorsed Tokyo’s ‘Quality Infrastructure’ concept. The three countries agreed in August 2018 to promote ‘Quality Infrastructure Development’ in the Indo-Pacific region. Government agencies from the US, Japan and Australia have agreed to provide joint financing for infrastructure in Asia. America’s Overseas Private Investment Corp., the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and Australia’s Export Finance and Insurance Corp. will cooperate to support energy projects such as liquefied natural gas terminals as well as infrastructure such as undersea cables.

Competing and cooperating with China

Tokyo’s policymakers obviously understand that Beijing smells containment in Tokyo’s ‘Quality Infrastructure’ policies. Security cooperation with the US, India and Australia in the ‘Quad’ framework further confirms the suspicion in Beijing that Tokyo and its like-minded partners are teaming up against China.

But there is more than just tensions and rivalry between Tokyo and Beijing. After initially refusing to consider joining the BRI, in July 2017 Japan announced that it would consider the possibility of becoming involved in BRI-related initiatives and projects if the latter met four preconditions. For Japan to contribute to Chinese-led BRI projects, they must be characterised by: (1) openness; (2) transparency; (3) economic sustainability; and (4) the ability of the developing countries involved to claim financial ownership over the projects in question. China, of course, refused to accept the Japanese preconditions, and it can be assumed that Tokyo was at the time well aware that its conditions would be unacceptable to China. In fact, the preconditions are arguably the very opposite of how many Chinese-led and Chinese-funded BRI project along the land and maritime Silk Road are being managed and operated. Nonetheless, Tokyo’s decision to consider cooperating with China on the BRI could make economic sense, since it would give Tokyo some opportunity to hold China to higher levels of transparency and accountability. In October 2018 Tokyo and Beijing agreed to set up a joint committee aimed at working on the possibility of jointly building a high-speed railway system in Thailand. That is (potentially) significant as Japan and China were recently competing for the high-speed railway system’s construction.14 Finally, during Abe’s state visit to Beijing in October 2018, Tokyo and Beijing signed a memorandum of understanding that foresees cooperation on up to 50 infrastructure investment initiatives in third countries.15 However, there are so far no details available on what kind of infrastructure projects Tokyo and Beijing are planning to cooperate on.

Teaming up with India

In December 2007 Abe declared that peace, stability and freedom of navigation in the Pacific Ocean are linked to –and depend upon– stability and freedom of navigation in the Indian Ocean.16 At the time the Japanese Prime Minister also spoke about cooperation between Japan, Australia, India and the US to secure and protect freedom of navigation in both the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. When Narendra Modi came to power as India’s Prime Minister in 2014 he announced the so-called ‘Act East’ policy, ie, an increased Indian involvement in politics and security in East and South-East Asia. In 2017 India and Japan then established the ‘Act East Forum’ to further institutionalise bilateral cooperation. During the Japan-India summit of 29 October 2018 in Tokyo, India and Japan furthermore discussed seven yen-loan agreements for key infrastructure projects in India, including the renovation and modernisation of the Umiam-Umtru Stage-III hydroelectric power station in Meghalaya and sustainable forest management in Tripura.17 Current Indo-Japanese infrastructure cooperation now stretches as far as Africa. The Asian-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC) initiated jointly by Tokyo and New Delhi is a project aimed at jointly promoting connectivity with Africa.18 The AAGC was announced at the Annual Meeting of the African Development Bank (AFDB) in India in May 2017. In the years ahead, the initiative will focus on four main areas: (1) development and cooperation; (2) ‘Quality Infrastructure’ and digital and institutional connectivity; (3) enhancing capabilities and skills; and (4) establishing people-to-people partnerships. Finally, it is possible that India will ask Japan to become a partner in the Trincomalee port construction in southern Sri Lanka, a project India was awarded in April 2017.19

Defence ties

The remnants of India’s non-alignment policies, it was often argued in the past, would deter New Delhi from committing itself to security and defence ties, which in Beijing could be perceived as part of Western-led containment against China. However, that has clearly changed since Beijing has begun attempting to turn the Indian Ocean into what Indian defence analysts fear could become a ‘Chinese lake’. Beijing’s massive investments in ports and other strategic industries in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, the Maldives and other countries in South Asia with access to the Indian Ocean are keeping India’s defence planners awake at night these days.

Chinese territorial expansion in the South China Sea and Chinese investments in strategic sectors in Pakistan, in particular, have become a concern in New Delhi. In September 2018 Beijing confirmed that it would be maintaining its commitment to invest US$60 billion in the so-called China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (which is part of the BRI). However, it should be borne in mind that Beijing’s public confirmation of its economic and military commitments took place against the background of the suggestion by the Pakistani Minister of Commerce, Abdul Razak Dawood, in September 2018 of temporarily suspending projects in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Pakistan leg of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.20 In January 2018 it was reported in the (non-Chinese) media (quoting a senior Chinese military official) that Beijing was planning to build an offshore naval base near the Pakistani Gwadar port on the Arabian Sea.21 If and when built, such a military base22 would become China’s second offshore naval base after having opened its first in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa in 2017. China has already invested heavily in the civilian facilities at Gwadar port and the second base would be used to dock Chinese naval vessels. While India –in view of its trade and investment ties with China– will continue to remain reluctant to allow its security cooperation with Japan to be portrayed as a fully-fledged ‘containment’ of China, Indian policymakers have turned to countering growing Chinese influence in general and fostering closer economic and military ties with Japan in particular. In October 2018 Japan and India established a 2+2 dialogue mechanism, ie, regular consultations between their respective Foreign and Defence Ministers. During a meeting between Japan’s Prime Minister Abe and his counterpart Modi in October 2018, Japan and India agreed to strengthen what is referred to as ‘maritime domain awareness’ by signing an agreement between their naval forces.23 Also in October 2018 Tokyo and New Delhi started negotiating a logistics-sharing agreement, the so-called Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA). The ACSA facilitates joint manoeuvres, including three-way exercises with the US Navy in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. The Japanese-Indian ACSA will give their armed forces access to each other’s military bases for logistical support. Under the agreement Japanese navy vessels will also be able to secure access to Indian naval facilities in the Andaman and Nicobar islands, located close to the western entrance to the Malacca Straits through which Japanese (and Chinese) trade and fuel imports pass. India has furthermore signed military logistics pacts with the US and France, both of which have naval bases in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.24

Europe calling?

There is not too much to report on yet, but Tokyo and the EU have already expressed their joint interest in cooperating on ‘connectivity’ and ‘Quality Infrastructure’. In October 2018, on occasion of the first EU-Japan ‘High-level Industrial, Trade and Economic Dialogue’, Tokyo and Brussels discussed future cooperation and coordination aimed at jointly increasing ‘connectivity’ in the Indo-Pacific. ‘Quality infrastructure’ cooperation it was agreed, would be part of the envisioned cooperation. And Europe and Japan already put their money where their mouths were in October 2018. The European Investment Bank (EIB) signed two Memorandums of Understanding (MoU), one with the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and another with Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI), aimed at extending loans for infrastructure projects in Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

Security cooperation with Europe and the EU in the form of what analysts also refer to as ‘Quad plus’ in the Indian Ocean region has also been thought of and talked about in Tokyo recently. However, while Tokyo undoubtedly welcomes European support for Japanese FOIP policies –including naval patrolling in the South China Sea–, European involvement will continue to be limited to France and the UK making tangible contributions. There seems to be yet little appetite in Brussels and among EU policymakers for increasing European involvement in Asian security through naval patrolling in Asian territorial waters (especially in those where China has territorial claims).25 However, in view of Chinese territorial expansion in the South China Sea in complete disregard and dismissal of international law –displayed by the construction of civilian and military facilities on disputed islands–, the EU’s insistence on not wanting to take sides in Asian territorial disputes (including those in the China Sea involving China) does not exactly add to the EU’s credibility as a foreign and security policymaker with a global reach, including Asia. Tokyo will continue investing resources and political capital in seeking to gain additional like-minded partner countries26 and partners to join its FOIP policy vision and strategy of a free, open and rules-based Indo-Pacific region. Next to Australia, the US and India, the UK, Canada, France, Singapore and also Vietnam27 are often cited in this context.

Conclusions

Japanese funds for ‘Quality Infrastructure’ in Asian and African development projects are substantial and Japanese companies have decades-long experience with infrastructure development and investments in African and Asian countries. Japanese ‘Quality Infrastructure’ investments have made sure that Beijing’s BRI is no longer the only infrastructure development game in town. While Tokyo’s FOIP emphasises the rule of law, human rights and democracy as its guiding values and principles, Tokyo continues to make exceptions as far as the insistence on democracy and rule of law are concerned. Indeed, Tokyo’s commitment to international law and democratic values is sometimes selective as in the case of the Philippines and Burma/Myanmar.28 Japan’s willingness, in principle, to cooperate with China on infrastructure development in Asia also makes political and economic sense. Recently, Abe asked Japan’s big trading houses to look into how they could participate in Chinese-led infrastructure projects.29

The expansion of Japan’s defence ties with India is substantive and together with its increasingly institutionalised security cooperation with the US and Australia in the ‘Quad’ context, it is without a doubt aimed at keeping China’s military and territorial ambitions in check. Finally, Japanese-European plans to become jointly involved in infrastructure/’Quality Infrastructure’ development is laudable but still at a highly embryonic stage. Both the EU and Japan have the economic instruments and financial means to jointly work on ‘Quality Infrastructure’ development projects in Asia, Africa and elsewhere and the recently adopted EU-Japan ‘Strategic Partnership Agreement’ (SPA) has created the necessary legal and operational basis. To be sure, Tokyo and Brussels have yet to start cooperating on ‘Quality Infrastructure’ development in Asia and elsewhere and the months and years ahead will show whether or not political rhetoric and declarations will catch up with reality, leading to results-oriented EU-Japanese cooperation on the ground.

Axel Berkofsky

University of Pavia & ISPI, Milan

1 J. Johnson (2018), ‘Japan to send helicopter destroyer for rare long-term exercise in South China Sea and Indian Ocean’, Japan Times, 22/VIII/2018.

2 Ibid.

3 See, eg, ‘Japanese submarine conducts first drills in South China Sea, Reuters, 17/IX/2018.

4 J. Sugihara (2018), ‘US, Japan and Australia Team on Financing Indo-Pacific Infrastructure’, Nikkei Asian Review, 11/XI/2018.

5 M.P. Goodman (2018), ‘An uneasy Japan steps up’, Global Economics Monthly, vol. VII, nr 4, Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), Washington DC, Apri.

6 Maria Abi-Habib (2018), ‘How China got Sri Lanka to cough up a port’, The New York Times, 25/VI/2018. Also see Kai Schultz (2017), ‘Sri Lanka, struggling with debt hands a major port to China’, The New York Times, 12/XII/2017. For further details on China’s investments in Sri Lanka in the framework on Beijing’s BRI see also Mario Esteban (2018), ‘Sri Lanka and great-power competition in the Indo-Pacific: a Belt and Road failure?’, ARI nr 129/2018, Real Instituto Elcano, 28/XI/2018.

7 ‘See China has a vastly ambitious plan to connect the world, The Economist, 26/VII/2018.

8 ‘G7 Ise-Shima principles for promoting quality infrastructure investment’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (MOFA).

9 Japan’s development agency responding to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

10 ‘Japan dedicated to making Indian Shinkansen a reality’, The Economic Times, 9/XI/2018.

11 The Japanese Shinkansen bullet train.

12 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) press release, 17/VIII/2017.

13 B. Lintner (2018), ‘Japan offers ‘quality’ alternative to China’s’, The Asia Times, 18/VIII/2018.

14 M. Duchatel (2018), ‘Japan-China relations: confrontation with a smile’, European Council on Foreign Relations, 1/X/2018.

15 S. Armstrong (2018), ‘Japan joins to shape China’s Belt and Road’, East Asia Forum, 28/X/2018.

16 Abe, Shinzo (2012), ‘Asia’s democratic security diamond’, Project Syndicate, 27/XII/2012.

17 ‘Why Northeast Asia matters for India-Japan collaboration in the Indo-Pacific’, The Economic Times, 31/X/2018.

18 Jagannath P. Panda (2017), ‘Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC): an India- Japan arch in the making’, Focus Asia – Perspective and Analysis, nr 21, August, Institute for Security and Development Policy Stockholm,.

19 ‘Sri Lanka to offer India port development to balance out China’, The Economic Times, 19/IV/2017; see also David Brewster (2018), ‘Japan’s plan to build a “Free and Open Ocean’, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, 29/V/2018.

20 ‘China says military backbone to relations with Pakistan’, Reuters, 19/IX/2018.

21 Cristina Maza (2019), ‘Why is China building a military base in Pakistan, America’s newest enemy?’, Newsweek, 5/I/2019. See also Minnie Chan (2018), ‘First Djibouti… now Pakistan port earmarked for a Chinese overseas naval base, sources say’, South China Morning Post, 5/I/2018.

22 Individuals in the Chinese military and government spoken to by the author continue to remain very reluctant to admit that what China is building will be a ‘real’ and/or ‘fully-fledged’ military base.

23 ‘India, Japan agree to hold 2+2 dialogue to enhance security in the Indo-Pacific region’, Economic Times, 29/X/2018; see also Roy Shubhajit (2018), ‘India, Japan decide to have 2+2 talks between Defence, Foreign Ministers’, The Indian Express, 30/X/2018.

24 Brahma Chellaney (2018), ‘The linchpins for a rules-based Indo Pacific’, The Japan Times, 28/X/2018.

25 European politicians and EU officials essentially fear Chinese economic and political repercussions should Europe ‘dare’ to increase its current involvement in Asian territorial disputes involving China.

26 ‘Like-minded’ in the sense of supporting and subscribing to Tokyo’s FOIP goals and vision.

27 Mentioning Vietnam and ‘like-minded’ in the same sentence is appropriate when the latter refers to Vietnam and Japan sharing the objective of freedom of navigation and a rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific as part of Tokyo’s FOIP. When comparing political systems, form of governance and the respect for freedom of speech and expression, Japan and Vietnam can hardly be referred to as ‘like-minded’.

28 James D.J. Brown (2018), ‘Japan’s values-free and token Indo-Pacific strategy’, The Diplomat, 30/III/2018.

29 ‘How to read Japan’s rapprochement with China’, The Economist, 25/X/2018.