Original version in Spanish: “No hay vida sin yihad y no hay yihad sin hégira”: la movilización yihadista de mujeres en España, 2014-2016

Theme

This analysis looks at the women who are recruited to join Islamic State in Spain: who they are, how they were radicalised and what their motivations and functions are within the groups, cells and networks in which they ultimately become involved.

Summary

The incorporation of women into the ranks of jihadist organisations in Spain has taken place within the context of the current mobilisation linked to the conflict in Syria and Iraq and the emergence of Islamic State as the leading organisation in the field, coinciding too with the emergence of jihadism of a home-grown character in Spain. Featuring their own distinct characteristics and patterns of radicalisation, such women share with their male counterparts both the goals of the global jihad and the means of securing it, taking a highly active role in promoting the caliphate, albeit at some remove for the time being from the front line of combat. This new development in jihadist mobilisation should not, however, be overlooked when it comes to addressing this type of terrorism.

Analysis

The rise of the Islamic State terrorist organisation as the new vanguard of the global jihadist movement and the establishment of its caliphate in Syria and Iraq in the summer of 2014 represented a turning point in the evolution of global terrorism. It was the advent of a third phase in the evolution of this phenomenon, characterised by a struggle for hegemony over jihadism between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda.1

In terms of jihadist mobilisation, the proclamation of the caliphate by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in a speech he delivered at a mosque in Mosul in June 2014 represented the realisation of a project that had hitherto seemed almost utopian, aspired to but never attained by al-Qaeda, whether under the leadership of Osama bin Laden or his successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri. Muslims were thus urged by al-Baghdadi’s explicit call to undertake the migration, or hijrah, to the caliphate, as reported in the third issue of the magazine Dabiq, published at around the same time, with one of its articles claiming that ‘there is no life without jihad and there is no jihad without hijrah’ and moreover that ‘this life of jihad is not possible until you pack and move to the Khilafah [caliphate]’,2 thereby freeing oneself from the slavery of working for infidels. This, along with the popularity the new organisation accrued thanks to the victories it notched up on the ground, was the spur for thousands of young people –male and female, hailing from over 180 countries– to make the journey to join Islamic State’s ranks and take part in the consolidation and expansion of a project with global scope.

It was a call that had an unprecedented impact on Western Europe: of the 30,000 foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) thought to have travelled to the Middle East to join the terrorist organisations active in the region, principally Islamic State, 5,000 hail from Western European countries. No previous jihadist mobilisation, whether linked to such important conflicts for the Muslim world as the conflicts in Afghanistan in the 1980s, Bosnia and Chechnya in the 1990s or the war in Iraq in the 2000s, had had such a wide repercussion among young European Muslims. The number of people mobilised for the conflict in Syria and Iraq between 2011 and 2016 is some five times the combined number of individuals who travelled to the aforementioned combat zones.3 We are therefore confronted by a mobilisation of unprecedented size, and for the first time it also contains a significant female contingent. Around 10% of the foreign terrorist fighters alluded to above, some 550, are women.4

In the Spanish case, according to the latest official figures, of the 208 individuals with Spanish nationality and/or residence in Spain that have decided to travel to the caliphate since 2013, some 10% (21) are female. But in addition another 23 women have been arrested and arraigned before the Audiencia Nacional within Spanish territory for their involvement in terrorist activities linked to Islamic State. This contrasts with the fact that prior to 2014 no woman had been prosecuted in Spain for activities related to jihadist terrorism. Nor had any significant arrest been made prior to that date. It is only in the current climate that women have become involved in terrorist activities of a jihadist nature within Spain’s borders.

This paper aims to offer a sketch of a phenomenon that is as yet empirically unexplored, namely female jihadist mobilisation in Spain. While it is not possible to provide a typical profile for these women, it is possible to point out the features that define and differentiate them, from a sociodemographic perspective, from their male counterparts. Various equally important aspects of their radicalisation processes, and the motives that led them to become actively involved in supporting Islamic State, will also be scrutinised. Lastly, the functions they have discharged within the cells, groups and networks (CGNs) to which they belong will be explored.

With regard to this latter point, there is a good deal of debate surrounding the role that these young Western women linked to Islamic State may play in the future, in light of the territory that has been lost in the Middle East. It may be that this change of circumstances sees women taking on tasks in the West that are highly restricted for them on the ground, such as the planning and carrying out of attacks. Alarm bells have been ringing in Europe in this respect since the arrest in Paris in early September 2016 of three radicalised women who, according to the French authorities, were preparing ‘an imminent act of violence’. It is to this debate that the present ARI, on the basis of the Spanish experience, seeks to provide input. It is an important issue when it comes to establishing the response to jihadist terrorism –which is constantly evolving and becoming increasingly complex– in Western Europe, something that inevitably also needs to be addressed from the gender standpoint.

On an individual level of analysis, the present study is based on the information gathered from the 23 women who have been arrested and arraigned before the Audiencia Nacional for activities related to Islamic State between 2014 and 2016. It was drawn up using data provided by the Elcano Royal Institute’s Global Terrorism Programme, contained in the Elcano Database of Jihadists in Spain (Spanish acronym: BDEYE), which gathers information about individuals arrested in Spain for terrorist activities of a jihadist nature derived from legally accessible court papers, attendance at public hearings, open sources and interviews with police experts. While the domain remains a small one, and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution, the author believes that enough empirical evidence is available to give a preliminary account of this new phenomenon, something that neither the state security apparatus nor society as a whole can afford to overlook.5

A home-grown phenomenon featuring young women free of family responsibilities

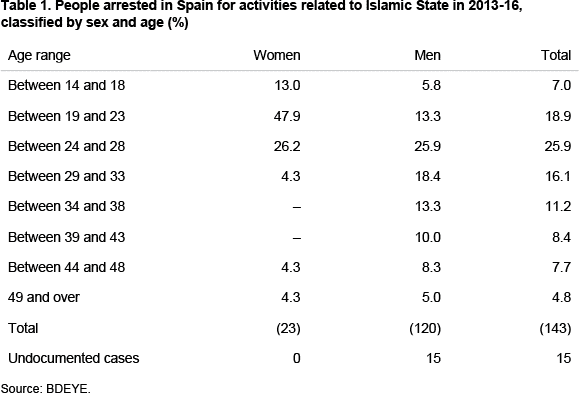

Between 2013 and 2016, a total of 158 people were arrested as part of various anti-terrorist operations against individuals, cells, groups and networks connected to Islamic State. Up to 14.6% of them were women, a more than significant percentage bearing in mind that until the emergence of Islamic State no women had been convicted for this type of crime in Spain.6 The first anti-terrorist operation in Spain that led to the arrest and subsequent prosecution of females took place in Ceuta, in August 2014, when a 14 year-old girl and a 19 year-old woman were detained by agents belonging to the National Police Force (CNP).7

Although youth is one of the most striking characteristics of the people arrested in Spain for activities related to Islamic State,8 in the case of women it emerges even more prominently. The average age of the women covered by this study is 24, seven years less than the average age of the men arrested for the same crimes: 31.3 years at the time of their arrest. Almost three quarters of the women (73.3%) were aged between 19 and 28 when arrested, and the age span with the greatest frequency was between 19 and 23 years old, accounting for almost half of the cases (47.8%), although below this two underage girls were arrested, the youngest being only 14. At the other extreme of the age spectrum, the eldest was 52. These data do not differ substantially from those of other Western European countries gathered in similar studies.9

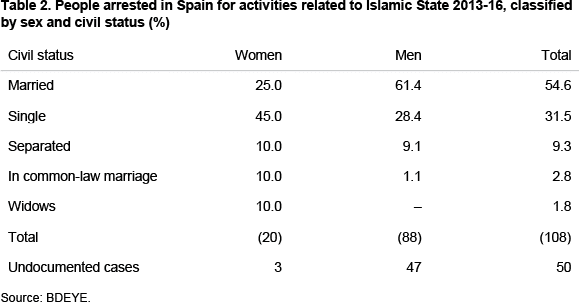

Another important variable for sketching the profile of women arrested in Spain for Islamic State-related criminal activities concerns their civil status, a variable where there are also notable differences between men and women. 45% of women were single at the time of their arrest, which is 16.6 percentage points higher than their male counterparts. By contrast, 61.4% of men were married, 36.4 percentage points greater than the women. There is also a percentage of widows (10%) –as opposed to zero widowers– who may be traced back directly to the case of two women who returned from the Syrian conflict after having lost their husbands, both foreign terrorist fighters.

In the context of this variable it is worth noting that, whereas 55.6% of the men had children at the time of their arrest, the majority of women (65%) did not have offspring. These results, taken together with those referring to age, are in keeping with Islamic State’s strategy of recruiting women whose identity is still in the process of being moulded, something that makes them particularly susceptible to adopting this extreme and rigorous vision of the Islamic creed. Moreover, they are related to other issues of a utilitarian nature, connected to the strategic need for these young women of childbearing age to settle in occupied territory, marry mujahedin and raise the next generation of jihadists.

Turning next to the nationality of the women arrested in Spain for connections to Islamic State, in more than six out of every 10 cases (60.9%) they were Spanish –more than half, 56.5%, were born in Spanish national territory– while three out of every 10 (34.8%) had Moroccan nationality –39.1% of them born in Morocco–. Of women with Spanish nationality, 65.2% were resident in Spain and the offspring of immigrants, born essentially in the autonomous cities of Melilla (36.2%) and Ceuta (27.4%). It is therefore a home-grown phenomenon, something that had already emerged in the current general context of jihadist terrorism in Spain. Another notable feature of the female contingent is that 13% are converts, lacking any manner of Muslim family, cultural or religious background, but who decided at a certain moment to adopt this faith as their own. It is a percentage similar to that observed among the men (11.1%).

Turning next to educational and occupational variables –and on the basis of the information available– it is evident that the women arrested in Spain were better educated than their male counterparts: none of the arrested women were illiterate or lacking any type of compulsory education, which is however the case with 8.8% of the male detainees. 87.5% of the women –compared with 25.7% of the men– had obtained secondary education, and 6.3% had completed higher education. In fact, according to the data available, 26.7% of the women were students at the time of their arrest, as opposed to 4.8% of the men, although this variable could be affected by the fact that the women are generally younger than the men. Another striking feature of the arrested women is the number who were unemployed, 33.3% of the total, 10 percentage points greater than the figure for unemployed men. In both cases, those in work were predominantly employed in the services sector.

Lastly, it is important to point out that at the time of their arrest for activities related to Islamic State none of the women had criminal records, whether for crimes related to terrorism or for ordinary infractions, something that by contrast is distinctly common among men, not only in Spain but elsewhere in Western Europe.10

Processes of radicalisation at the speed of the Internet

Among the women arrested and brought before the courts in Spain for Islamic State-related activities between 2014 and 2016 there is not a single case of self-radicalisation. All the women covered by this study acquired the ideology of jihadist salafism that led them to become involved in terrorist activities, whether in a physical or virtual setting, in the company of other women and under the guidance of a radicalisation agent, as shall become evident in what follows. In eight out of 10 cases this radicalisation process was endogenous in nature, in other words it took place at least in part within Spanish national territory, mainly the autonomous city of Ceuta for three out of 10 women (26.3%) and, for two out of 10, in the provinces of Barcelona (23.2%) and Madrid (19.2%).

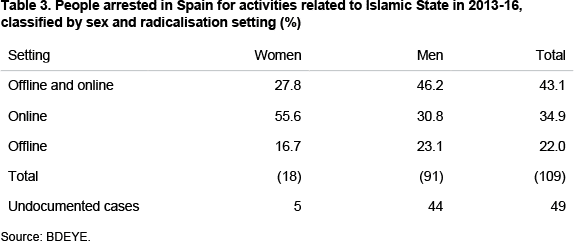

The Internet has enabled women to insert themselves into radicalisation settings that would hitherto have been off-limits to them, thereby gaining access to jihadist propaganda. Thus, and in line with the campaign that Islamic State has explicitly run on social media to persuade women to partake in consolidating the project of the sharia-law governed ‘pseudo state’ in the Middle East, it is evident that women tend to become radicalised to a greater extent than men in an online setting. More than half of the women, 55.6%,thus became exclusively radicalised in this setting as opposed to 30.8% of men. By contrast, the women who became exclusively radicalised in an offline setting (16.7%) are 6.5 percentage points below the men who became radicalised in this way (23.1%). Although the predominant setting for women is exclusively virtual, for men it is the setting that combines online and physical encounters (46.2%), which is also the case for almost three out of 10 women (27.8%).

In the case of the online setting, the places where women underwent their processes of violent radicalisation were as follows: social media, for nine out of 10 detainees (93.3%), followed by mobile messaging applications, used by eight out of 10 (80%) and finally, forums and blogs, used by two out of 10 (20%). None of these places is exclusive and normally they are combined with each other, each playing a different part within the process.

What usually happens with online radicalisation is that, after making initial contact through pages or profiles in social media, where recruiters are searching for potential targets, and as the relationship becomes stronger, the activity is channelled towards more private and secure settings such as chats installed on mobile devices, through which the young woman being radicalised receives all manner of jihadist audiovisual content, and takes part in conversations about the content, either individually or as part of a like-minded group. Sometimes, the groups created in messaging applications and social media pages tend to reproduce the segregation by sex that exists in the more conservative and rigorous Islamic settings, with only women being admitted.

A striking feature of the indoctrinators, or radicalisation agents, in the virtual setting referred to above is the influence exerted by people considered to be ‘peers’ of the arrested women. In other words, the relationship is not founded on a situation of hierarchical superiority, underpinned by the indoctrinators’ contacts, charisma or social position. This was the case for almost seven out of 10 women (66.7%). Foreign terrorist fighters were involved in four out of 10 cases (41.7%). Lastly activists –charismatic members with contacts within the organisation concerned– played the role of radicalisation agent in rather less than two out of 10 cases (16.7%).

A good example of a radicalisation process in an online setting, involving various platforms and the participation of various radicalisation agents, is that of a 24 year-old Moroccan woman resident in the province of Barcelona, who on a visit to the country of her birth with her child, while her husband was out of Spain for work reasons, started to visit various social media sites with jihadist content, to which she became ‘hooked’.11 On these platforms she came into contact with a foreign terrorist fighter of Syrian origin and his sister, who tried to radicalise her by means of constant messages endorsing the caliphate. As the process advanced, the young woman struck up a relationship with a second fighter, who in turn put her in contact with a military commander with whom she ended up getting engaged. She held simultaneous conversations via various messaging apps with Wahhabi sheiks living in various countries in the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa, whom she queried about a range of religious precepts. She also communicated with a husband and wife team of activists in Austria, who gave reasons supporting jihad and the decision of a woman to travel alone and unchaperoned to Syria. This was finally what she did, in the company of her three year-old child; the child was the offspring of her husband in Spain, from whom she was in the process of obtaining a divorce.12

As far as the radicalisation processes of women in an offline setting are concerned, these mainly took place in private homes –a highly common setting among jihadists in Spain before and after 2013– and in places of worship and Islamic cultural centres. In this case the activity between the two settings was sometimes complementary in the sense that, after making initial contact in the virtual world, a physical encounter took place between the women undergoing radicalisation and their agent or agents so that a stronger and more trusting relationship could be established, enabling the agents to increasingly influence the attitudes of the women on their path towards jihadist involvement.

The indoctrinators most frequently involved in face-to-face processes were people within the women’s close circles, such as family members (accounting for 42.9%) and friends (28.6%), in contrast to the situation among men, where activists were the most frequent agents of radicalisation. This also points to the more closed atmosphere in which the radicalisation of women takes place. It is again worth emphasising that one and the same person was sometimes exposed to the influence of various indoctrinators.

A highly pertinent case in this context is that of a 20 year-old woman from Ceuta who was arrested in Turkey on her way to the caliphate. She was influenced in the ideological trajectory that led her to undertake this journey by one of the two leaders of the first Islamic State-related jihadist cells to be dismantled in Spain, in the summer of 2013, who was a member of her family. He had also recruited and sent to Syria one of the young woman’s cousins, with whom she was very close. Another example of a mixed radicalisation in which the offline dimension played a determinant role is provided by the case of woman from Ceuta who was arrested in the summer of 2014 on the Spanish-Moroccan border when planning an imminent journey to Syria. Once detained she told the authorities that she had changed her moderate views of Islam after a attending a mosque in Ceuta where the imam, who had travelled from Morocco to preach, ‘praised those who journeyed to Syria and Iraq, deeming them brave because they fought for Allah’.13

In any event, the enormous influence of the Internet and social media on young westerners ensures that propaganda reaches them rapidly, directly and in a language that resonates with them, resembling nothing so much as a marketing campaign tailor-made for its market. This has had a major bearing on the fact that violent radicalisation processes have become speeded up and conclude just a few months after starting. All the women in this study for whom information is available completed their radicalisation processes barely a year or even less from the time they began.

A better life in a project under construction

Before delving into the roles played by the women arrested in Spain for Islamic State-related activities between 2013 and 2016, it is worth enquiring about the motivations that led them to become involved in terrorist activities of a jihadist nature, in order to determine whether the women acted for the same reasons that impelled their male counterparts or whether, on the contrary, they involve another series of individual motives for pursuing a path towards violence.

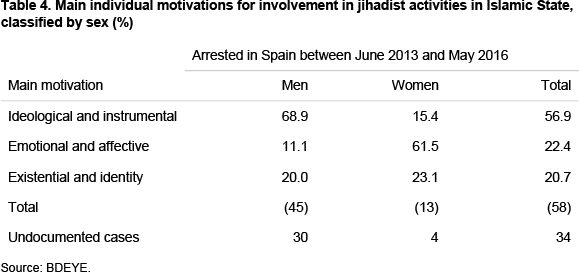

While it is true that both men and women share the goals of Islamic State and the means for attaining them, the motives that disposed them to become actively committed to obtaining them are strikingly different. As far as the women are concerned, six out of 10 (61.5%) are more inclined to embark upon jihadism for reasons of an emotional or affective nature, including the promise of getting married to a fighter in the field, with whom they typically fall in love over the internet, or whose partner persuades the women to become involved with them. Such motivations are relevant to only one out of 10 of the men (11.1%), who tend to base themselves more on an ideological commitment to the principles and values of jihadist salafism or on instrumental reasons, such as acquiring status, a salary or attaining paradise (68.9%). Such incentives are the main cause for becoming involved for only 15.4% of the women. The data for the two kinds of motivation are therefore almost inverted when comparing sexes. Where the sexes coincide is in the fact that for both two out of 10 men (20%) and women (23.1%) existential and identity causes were the main driving factor in their terrorist involvement. The situations grouped under this heading include lacking a definite identity, a crisis caused by the loss of a loved one, a lack of inspiring life prospects and frustration.

A striking example of those attracted by the promise of marriage and the prospect of a family by settling in the caliphate is provided by the case of a 22 year-old Spanish woman, arrested at the airport in Madrid en route to Turkey in October 2015. She had converted to Islam just a few months prior to the journey and had decided to take this step after establishing a sentimental online relationship with an individual from North Africa, whom she was going to marry once both of them reached Syria.14 Meanwhile, in the case of a young Moroccan women who was also arrested on her way to the caliphate in 2015 in the company of her son, there were two motivations: the promise of marrying an FTF of certain rank in the caliphate, ‘a real man’ in her own words, and that of seeing her expectations of a better life in Spain –which she had entered as an economic migrant– thwarted.15 Lastly, an illustration of ideological causes is provided by the case of a 19 year-old woman, also of Moroccan nationality, arrested in the province of Alicante in September 2015. In the mobile devices found at the time of her arrest the investigators discovered numerous photographs of armed women in combat mode. One in particular showed a woman dressed in a black niqab that covered her completely, carrying the Islamic State flag and overprinted with the text ‘Strong and the strength of my God. In favour of the Islamic State’.16

There is no jihad without hijrah

In terms of the way in which the women arrested and brought before the courts in Spain for connections to Islamic State became involved in Jihadist activities, it is striking that all of them did so in the company of others, and that they belonged to CGNs with a degree of structure and internal hierarchy. There are no cases therefore of women who adopted the postulates of Islamic State on their own and sought to act in their name. Thus all of them became involved with others and moreover had some kind of organisational link with the terrorist entity based in the Middle East, whether directly or through another member of the CGN to which they belonged.

As far as their position with the CGNs is concerned, and applying the concentric circle model17, which conveys the importance and degree of responsibility wielded by each, it is striking that only one of the 23 arrested women is located in the centre, where the CGN leaders and coordinators are situated along with other notable militants dedicated to tasks of indoctrination. The only detainee involved in the nucleus of a CGN devoted herself both to indoctrinating other young people and coordinating the activities of other recruiters in the same network. Six out of 10 detainees were located in the second circle, where a greater variety of activities is to be found; typically, they were involved in the apparatus used to transfer other militants of the same sex to Syria and Iraq. Lastly, three out of 10 detainees were located in the outer circle, having fundamentally been recruited to be sent to Syria and Iraq. In comparison to the women, their male counterparts tend to occupy a greater number of leadership roles –three out of 10 (28.4%)– while those located on the periphery represent less than half the women in this third circle, 17.5% less. The majority of men are to be found in the intermediate circle, accounting for 55.8% of the total.

A good example of the active but secondary role of women is provided by the Kibera network, where despite being in charge of recruiting and indoctrinating other women on Spanish soil, the women were on the receiving end of instructions from the network leaders: two men based in Morocco.18

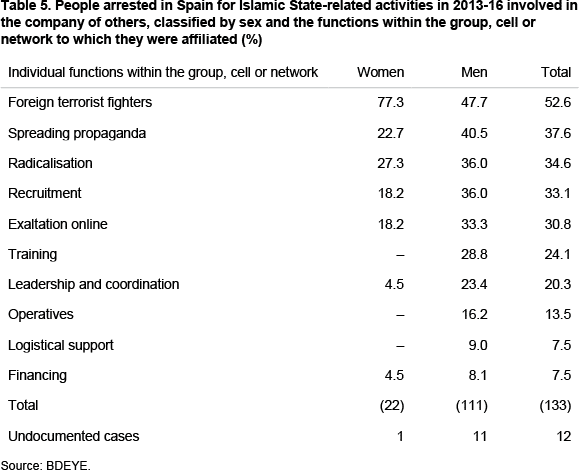

Turning now to the individual roles played by each of these women, and bearing in mind that normally two or more tasks were undertaken simultaneously, almost eight out of 10 (77.3%) were willing to travel to the caliphate and involve themselves directly in its construction. That is to say, their intention was not so much to wage ‘jihad at home’ as to travel to the territory occupied by Islamic State in order to join the project of the caliphate under construction, but without getting involved in fighting.19 This also emerges from the fact that none of the women performed functions of an operational nature, nor had they been trained physically or in the use of weapons or explosives. In the case of the men, willingness to become involved as foreign terrorist fighters also predominated, provided they had not already been arrested before being able to achieve this goal, although the percentage is notably lower than among women (47.7%).

Other functions performed by the women arrested in Spain include recruiting and radicalising other women (accounting for 45.5%) and spreading propaganda over social media and the internet (22.7%). Also notable are those engaged in praising their terrorist organisation online (18.2%). All these tasks are also performed by a significant number of men, who encompass a wider range of roles, including operational, training, leadership and coordination duties.

It should be noted however that in their various roles the women detained in Spain have made their firm commitment to Islamic State patently clear, publicly demonstrating their acceptance of violence as a form of achieving a political end and justifying the extreme measures the organisation inflicts on its enemies.20 For example, a 19 year-old woman arrested in Fuerteventura, born in Morocco but brought up in the Canary Islands, had publicly proclaimed –no less than twice– her loyalty to Islamic State on social media, glorifying the use of violence as a means of punishing the ‘infidels’ and ‘enemies of the caliphate’. Commenting on a video released by the terrorist organisation after the execution of a Jordanian pilot on 24 December 2014 in Syria she wrote: ‘every time I watch the video of Muad being executed and how he dances in the flames I kill myself laughing, although the first time I saw it I burst into tears, not out of compassion but out of fear of the flames of hell’.21

Conclusions

The mobilisation of women for the jihadist cause has emerged in Spain within the framework of the current mobilisation linked to the conflict in Syria and the appearance of the Islamic State terrorist organisation as the new vanguard of global terrorism. The women who have been arrested and arraigned before the Audiencia Nacional for jihadist activities tend to be young and free of family responsibilities, second-generation Spaniards born to Moroccan parents –born in Melilla or Ceuta– and predominantly therefore from Muslim backgrounds, although there is a significant number of converts. While none of the young women was illiterate, the majority had only managed to complete secondary education and were indeed occupied as students –with various degrees of success– at the time of their arrest. A third of them were unemployed. None of the women had criminal records for terrorist crimes or any other sort of infraction, and therefore at the time of embarking upon investigations they were unknown to the police and judicial authorities.

The radicalisation processes were endogenous –undertaken mainly in Ceuta, Barcelona and Madrid– and always took place in the company of others, in a predominantly online setting, resorting both to the internet and all manner of social media as well as messaging applications installed on mobile devices. They were guided in this process by a radicalisation agent, prominent among whom were other individuals, similar to the women themselves, or a foreign terrorist fighter supposedly operating on the battlefield.

In the Spanish case the involvement of women in Islamic State is mainly related to the promise of a life in the caliphate, of a foreign terrorist fighter whom they hope to marry, or to the frustration of not being able to lead a life in keeping with their expectations in their place of residence. It is, however, a complex process in which other factors of various kinds play a part. Thus the role of these women has focused on their willingness to participate in the jihadist project in the occupied territory, assimilating the doctrinal roles mentioned in the organisation’s texts, which continue to be highly conservative.

This does not entail that amid the decline of the caliphate in the Middle East their functions in the West will not evolve towards a more active role in the preparation and carrying out of attacks. The use of women in operational activities of a suicidal nature has proved to be a win-win strategy for the organisations, providing they are not arrested before achieving their goals: first it has been calculated that they are capable of causing up to four times as many victims as their male counterparts, given their greater ability to pass undetected,22 and secondly they attract much greater media coverage, owing both to their novelty (men are traditionally over-represented in terrorist organisations), and to the shock that is still felt upon seeing a woman commit violent acts, when they have traditionally and culturally been associated with peaceful values.23

Thus, amid the difficulties it faces on the ground, Islamic State may be contemplating a strategic switch to demonstrate its strength. It should not be forgotten that while life in the caliphate is subject to stringent measures of social control in terms of the behaviour that women must adhere to in all aspects of their lives, these do not apply with such rigour on European soil and it would be less serious to transgress them from a doctrinal perspective. By the same token, if their plans of undertaking hijrah to the caliphate are frustrated, or they return from the caliphate, the women in question could decide to wage jihad at home, heeding the calls of the former spokesperson for Islamic State, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, to attack their own Western countries of origin, published in the magazine Rumiyah at the end of 2016 and elsewhere.

All the foregoing means we must not underestimate the threat to security for countries such as Spain that could be posed by women recruited from the West into the global jihadist movement. This necessarily entails taking anti-terrorist measures and working on measures to prevent violent radicalisation, especially in the online setting, using the insights gained from gender analysis. De-radicalisation programmes also need to be designed that are tailored to their profiles and circumstances. Prisons and juvenile detention centres, places that have hitherto been removed from this issue and are now housing the first inmates convicted by the courts, will constitute a particularly sensitive environment.

Carola García-Calvo

Analyst in the Global Terrorism Programme at the Elcano Royal Institute | @carolagc13

1 Fernando Reinares (2015), ‘Yihadismo global y amenaza terrorista: de al-Qaeda al Estado Islámico’, ARI nr 33/2015, Elcano Royal Institute, 1/VII/2015.

3 Thomas Hegghamer (2016), ‘The future of jihadism in Europe: a pessimistic view’, Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 10, nr 6, quoting data from the Soufan Group.

4 Bibi van Ginkel & Eva Entenmann (Eds.) (2016), ‘The foreign fighter phenomenon in the European Union. Profiles, threats and policies’, ICCT Research Paper, April.

5 The author would like to express her gratitude at this point for the valuable comments of Fernando Reinares, director of the Elcano Royal Institute’s Global Terrorism Programme, and the work of Álvaro Vicente, research assistant on the Programme, not only for their work in managing the BDEYE but also for their immeasurable help in drawing up this ARI.

6 See Fernando Reinares & Carola García-Calvo (2013), ‘Los yihadistas en España: perfil sociodemográfico de condenados por actividades terroristas o muertos en acto de terrorismo suicida entre 1996 y 2012’, Working Document, nr 11/2013, Elcano Royal Institute, 26/VI/2013.

7 First phase of Operation Kibera.

8 See Fernando Reinares & Carola García-Calvo (2016), Estado Islámico en España, Elcano Royal Institute, Madrid, chap. 1.

9 See Anita Peresin (2015), ‘Fatal attraction: Western Muslims and ISIS’, Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 9, nr 3.

10 For Spain, see Reinares & García-Calvo (2016), Estado Islámico en España, op. cit., and, for Europe, Rajan Basra, Peter R. Neumann & Claudia Brunner (2017), ‘Criminal pasts, terrorist futures: European jihadists and the new crime-terror nexus’, ICSR.

11 Patricia Ortega Dolz (2015), ‘Samira, la “reclutadora” de mujeres del Estado Islámico’, El País, 14/III/2015.

12 Audiencia Nacional, Criminal Court, Section 4, Sentence 38/2016, 15/XI/2016.

13 Juzgado Central de Menores de la Audiencia Nacional, Reform file 5/2014.

14 Antonio R. Vega (2015), ‘La yihadista de Almonte contactó con el islamismo en Sevilla’, ABC Andalucía, 25/X/2015.

15 Ortega Dolz (2015), op. cit.

16 Oral hearing of the summary trial /2014, session of 6/I/2017 at the Audiencia Nacional (Madrid), testimony questioned by the state attorney at 11:35.

17 For more information see Carola García-Calvo and Fernando Reinares (2016), ‘Patterns of involvement among individuals arrested for Islamic State-related terrorist activities in Spain, 2013-2016’, Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 10, nr 6.

18 DGP, CNP, CGI (2014), ‘Informe de situación de la investigación’, JCI nr 1, Audiencia Nacional, Pre-trial proceedings 71/2014, 11/XII/2014, p. 315.

19 For further information, see ‘Women of the Islamic State. A manifesto on women by the Al-Khanssaa Brigade’, translation and analysis by Charlie Winter, Quilliam Foundation, 2015, and ‘Letter to our sisters, “Jihad without fighting”’, Dabiq, nr 11.

20 On this point, regarding the experience of other Western countries, see Melanie Smith & Erin Marie Saltman (2015), ‘Till martyrdom do us part’, Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

21 ‘Las amenazas de la yhadista canaria encarcelada: “Vuestra sucia sangre correrá por España”’, El Español, 24/VII/2016.

22 Mia Mellissa Bloom (2010), ‘Death becomes her: the changing nature of women’s role in terror’, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol. 11, nr 1, Georgetown University Press, p. 91-98.

23 Carola García-Calvo, ‘El papel de la mujer en la yihad global’, Revista de Occidente, nr 406, March.