(*) Original version in Spanish ‘El precio de la ciudadanía española y europea‘.

Theme: The rules on accessing nationality are very different from one EU member state to another. Spain offers the fastest route for most of its immigrants from non-EU countries.

Summary: In the last 12 years, Spain has granted nationality to more than a million people. Although the Spanish Civil Code sets a 10-year residency requirement before citizenship can be requested, most of the immigrants in Spain from outside the EU –Latin Americans– are exempted from this rule. As a result, Spain in practice grants citizenship with a much lower residency requirement than the European average of over six years. In addition, 503,000 people have requested Spanish nationality under the provisions of the Historical Memory Law and a recent proposal could extend this to an unknown number of Sephardic Jews. We propose here that the rules on accessing nationality should be modified.

Analysis: Obtaining citizenship of an EU member state grants very substantial rights within the EU as a whole, and yet there has been no attempt to date to homogenise the national rules which regulate access to nationality. By very different routes and following diverse requirements, European citizenship is sometimes secured very quickly, as in the case of Latin American immigrants in Spain, and sometimes very slowly, as in Austria or in Spain itself with immigrants of other origins.

The rules on accessing nationality in the different countries are usually the result of some combination of ‘right of blood’ (ius sanguinis) and ‘right of soil’ (ius soli). The first refers to the individual’s filiation to his/her parents and ancestors (for example, a descendant of Germans is German) and the second to the acquisition of nationality by means of residency: an individual becomes German, regardless of his family origin, by requesting nationality after eight years in the country. In Spain ius sanguinis comes first (all the children of Spaniards are Spanish), though it is qualified by numerous provisions on access to nationality by means of residency, marriage or birth on Spanish soil:

- The Civil Code grants Spanish nationality to those born in Spain, regardless of the nationality of their parents. These can request nationality for their child after he/she has been in the country for one year. In the past decade, the number of children born to a foreign father or mother increased annually at a rate of 10,000, from 41,000 in 2001 to 108,000 in 2007 and 109,000 in 2011.[1]

- The Code also facilitates access to nationality to the children or grandchildren of Spaniards born in Spain who, for whatever reason, have not maintained their Spanish nationality. This option, introduced in the 2002 reform of the Civil Code, was designed to provide citizenship to the children and grandchildren of former Spanish emigrants.

- Nationality is granted to children born in Spain in cases where the origin countries of their parents do not grant them citizenship since they have been born abroad. This is the case of the children of many of the Latin American immigrants born in Spain (Argentines, Ecuadoreans, Bolivians, Brazilians, Colombians, Cubans, Chileans, Paraguayans, Peruvians and Uruguayans).[2]

- Marriage to a Spaniard is another way of accessing nationality; in this case, one year of legal residence is required to request citizenship. This door to nationality is the most liable to abuse and is therefore subject to particularly close surveillance.[3]

- The children of parents born in Spain have access to Spanish nationality, even if the parents themselves do not have Spanish nationality. This will have a significant impact in Ceuta and Melilla within a couple of decades since for years large numbers of women from provinces in northern Morocco have given birth to their children in the hospitals of both Spanish border cities. The grandchildren of these women will be able to request Spanish nationality as the children of someone born in Spain.

- The Historical Memory Law[4] opened up a new route to Spanish nationality by offering it to the grandchildren of those who lost their nationality as a consequence of being exiled during the Civil War or the post-war period, and to the children of those who had Spanish nationality but lost it for some reason. In the second case, the possibility was available for two years, later extended to three. The law’s application has resulted in 503,000 requests for Spanish nationality, 90% of them from Latin America, and around 300,000 have so far been settled favourably. The rest are still being processed. Very few of these requests relate to the grandchildren of those exiled.

However, the route most used to access citizenship is residency. In this regard, Spanish regulations generally demand 10 years of legal residence for an individual to be able to request nationality, though the period is reduced to two years in the case of nationals from all of Latin America, Portugal, Andorra, the Philippines and Equatorial Guinea and of Sephardic Jews. Refugees, a very small group in Spain, can request nationality after a period of five years of residency. Since immigrants from Latin America account for 56% of all non-EU immigrants, this two-year exception is in fact applied to most cases. Thus in 2011 (the latest year for which data are available), of the 114,599 individuals granted Spanish nationality, 72% were processed via the two-year residency route. Much further behind were the marriage (10%), 10-year residency (9%) and birth in Spain (8%) options. Seventy-eight per cent of the citizenships granted were to Central and Southern America nationals. It should be borne in mind that citizens from other EU countries resident in Spain –2,354,561 people according to the Municipal Register (Padrón) as of January 2013– rarely request Spanish nationality: their EU citizenship offers them very similar rights to those of Spaniards, with the exception of the right to vote in general and regional elections, so that nationality for them is not a key element in their integration or wellbeing. On the other hand, and in marked contradiction to the European spirit, there are very few dual-nationality agreements between European states. Spain only has dual nationality agreements with the countries mentioned above that benefit from the two-year exception rule, so that citizens of almost all EU countries that acquire Spanish nationality supposedly lose their own.

Figure 1. Annual cases of Spanish nationality granted by residency

Source: Permanent Immigration Observatory (Spain).

The decline recorded in 2011 is due to the backlog in the services of the Ministry of Justice, which reached 400,000 dossiers in 2012, due to the high number of nationality requests. In an unprecedented move, the Ministry reached an agreement with the Association of Property Registrars in Spain whereby they would examine the requests and report on them, without being paid to do so. They were assigned 350,000 dossiers and 83% of their recommendations (244,000 as of last February) have been to grant nationality.[5] Although the Ministry of Justice has the final decision, it can be assumed that it will generally accept the Association’s proposal, which means more than 200,000 new awards of Spanish nationality to add to the numbers already reached. The Association will continue in this task at least until the end of 2013, in this case with the new requests which have been presented during 2012 and 2013, totalling around 12,000 per month.[6]

Figure 2. Nationality by access route, 2011

Source: Permanent Immigration Observatory (Spain).

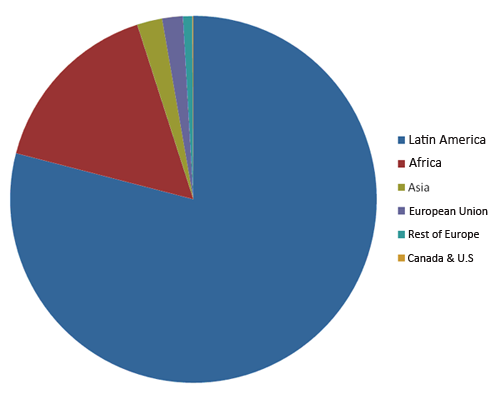

Figure 3. Nationality by origin, 2011

Source: Permanent Immigration Observatory (Spain).

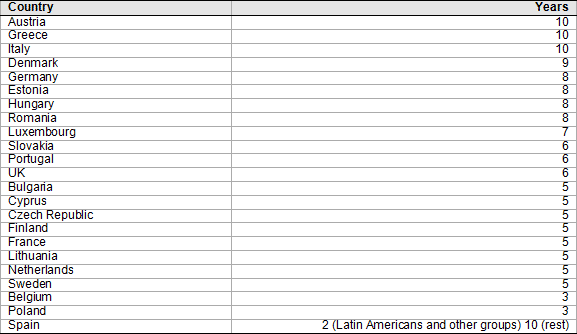

In comparative terms, Spain is the EU country where it is easiest for most non-EU immigrants to gain citizenship. In fact, Latin American immigrants gain citizenship long before they obtain their permanent residence permit, which is secured after five years of legal residency and gives the right to stay and work throughout the entire EU (long-term residence permit). Although other countries also have specific regulations to benefit those they consider closest in cultural or ethnic terms, akin to the Spanish rules regarding Latin Americans, the immigrants of those origins do not account for such a sizeable proportion of total immigration as Latin Americans do in the Spanish case. Germany, for example, whose system is the best known expression of ius sanguinis, grants nationality to all those who can prove they are of German descent, even if their forebears have not set foot in what is now Germany for centuries. The same occurs in other nations with sizeable diasporas, such as Greece, or which have lost sovereignty over lands populated by former co-nationals, such as Hungary. But in all these cases the migrants that gain nationality by this route account for a small percentage of the total immigrants in each country, or they are countries where the level of immigration is very low. This is in marked contrast to the Spanish case, which has received the largest number of immigrants of all EU countries over the last decade, and where the legal exception has become the statistical majority among non-EU immigrants. It is also important to highlight that Spanish rules are not matched by those of Latin American countries in terms of access to nationality. In other words, Spaniards do not benefit there from special treatment to obtain citizenship.

Figure 4. Years of residency required to request nationality

Source: Eudo Observatory Citizenship.

Despite the fact that access to nationality is faster in Spain than in any other EU country for most of its non-EU immigrants, the main European index that evaluates integration policies, MIPEX (Migrant Integration Policy Index),[7] gives Spain a low score in this regard because it only reflects the 10-year residency requirement, and not the two-year exception. This paradox unfairly damages the reputation of Spanish integration policies, which nevertheless score highly in the remaining areas.

Together with the most commonly used routes to access citizenship, there are various others used very infrequently, such as ‘nationality by naturalisation’, which is granted in a discretionary manner and has notoriously been applied to elite sportsmen and women and other exceptional cases for a wide variety of reasons. In recent years, some of these instances have benefitted Sephardic Jews who are nationals of countries in which they suffer from social or institutional harassment. In this context, some months ago the Ministry of Justice presented an invitation to extend the granting of nationality to all Sephardic Jews, a community whose size is estimated at around 3 million people and which to a large extent has kept alive its Spanish identity, especially as to language. The project, which was presented as a gesture to redress the injustice committed by Spain in driving out the Jews in 1492, has not advanced since then, but its publicity has raised many expectations and requests to obtain Spanish nationality among the Sephardic Jews living in various countries.[8] If the proposal goes ahead, the opening of this new route could lead to protests from the other large collective expelled from Spain, the Moors, who outnumber the Jews and were banished more recently (during the reign of Philip II of Spain, in 1609). The banished Moors, unlike the Sephardic Jews, soon lost their Spanish identity, essentially meaning the language. But if the purpose of the exercise is to redress iniquities, it could be argued that both expulsions were equally unjust.

Conclusion and proposals: Access to nationality enables the full incorporation into the human collective that defines the basis of the state, which is why all states have rules that regulate it. The permanent solidarity network that exists between those belonging to the nation –and which is expressed, among other means, by taxes and the distributive and cohesive role of the state– cannot be opened indiscriminately to any and everyone who decides to become a part of it. For this reason, all states require individuals to have resided in the country for a set period of time as a prior process to becoming integrated in their society. Many also add exams to test mastery of the official language and knowledge of the country’s culture, history and political system, a growing trend which Spain is going to join. Holding ceremonies for gaining access to nationality with varying degrees of solemnity, as many countries do, is also a means of giving a value of personal identity to nationality, beyond its instrumental benefits –an aspect which Spain has paid little attention to–.

In the case of the EU, the citizenship of each state is superimposed by a European citizenship which is basically acquired through national-level citizenship. However, no steps have been taken towards homogenising the rules regarding access to nationality in each of the member states, or towards automatic recognition of dual nationality among nationals of any of the EU member states.

In this context, Spanish regulations, combined with the pre-eminence of Latin American immigration, have made the route to citizenship less costly on average in Spain than in any other EU country. Almost three quarters of new Spaniards have gained citizenship by the two-year residency requirement option, which is far lower than the average requirement of 6.4 years in the various European countries.

The high number of new nationalisations granted in Spain has effects of many kinds, including a reduction in the capacity of the Spanish state to manage migratory flows since all Spanish citizens have the right to family reunification of their spouses, children under 21 and parents (both their own and those of their spouse). These family members, in turn, access citizenship over time and become holders of these same rights. Another effect, which relates to the current financial crisis, is the increase in the arrival in other countries of emigrants that have recently acquired Spanish nationality, both in the EU and on the other side of the Atlantic, with sometimes detrimental consequences.[9]

A process of European regulatory convergence is needed regarding access to citizenship in each state, since this affords rights in all the others. But, in the meantime, Spain should come closer to the average by, on the one hand, substantially reducing the legal residency period (10 years) that the Civil Code requires prior to nationality requests, and, on the other, by removing the exception (two years) that is applied to the nationals of so many countries. A common rule for both, which does not discriminate according to origin, and which were to demand, for example, five years of legal residency –the most common requirement within the EU, which coincides with the period required to obtain the long-term European residency permit– would be more just, more beneficial for the reputation of Spanish integration policy and more appropriate for Spain’s external relations as to population mobility.

Finally, it would be advisable to review the relevance of the access to nationality for the children of a father or mother who was born in Spain and yet never had Spanish citizenship. This can apply in the case of both a pregnant tourist who accidentally gives birth in Spain and to women from the north Moroccan provinces who have gone to hospitals in Ceuta and Melilla to give birth. It is not at all clear on what principle the right to Spanish nationality of the future children of these children is based.

Carmen González Enríquez

Senior Analyst for Demography and International Migrations, Elcano Royal Institute

[1] Statistical Yearbooks on Foreign Residents by the Permanent Immigration Observatory and Vital Statistics, National Institute of Statistics (INE).

[2] On access to nationality by birth in Spain, see Nacionalidad de los hijos de extranjeros nacidos en España, by Aurelia Álvarez Rodríguez and the Permanent Immigration Observatory.

[3] As well as marriage itself, certified common-law marriage has also become a means of access to a residence permit and, indirectly, nationality. This second route, more simple and less closely monitored, is more open to fraudulent practices.

[4] Law 52/2007, of 26 December, to recognise and extend rights and to establish measures in favour of those who suffered persecution or violence during the Civil War and the dictatorship.

[5] El País, 21/II/2013.

[6] http://www.mjusticia.gob.es/cs/Satellite/es/1288777650107/EstructuraOrganica.html.

[7] http://www.mipex.eu/.

[8] See, for example, the article in the New York Times of 20/V/2013 on the expectations of US Sephardic Jews.

[9] Spanish nationals have become the most rejected Europeans at US airport border controls. US regulations exclude from the visa waiver system those nationals of any country for which more than 3% of entries have been refused at the US borders. Spain is still far from reaching this ceiling, but the number of rejections is increasing.