Theme

The Northern Ireland Protocol has become the thorniest issue in the new relationship between the UK and the EU.

Summary

The Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP), signed by the UK and the EU as part of the Withdrawal Agreement in 2020, has become the thorniest issue in the new relationship between the two sides. In the run up to the 2016 referendum there was almost no consideration, let alone discussion, of the implications for the Northern Ireland peace process that a Brexit vote might have. Since 2020 the discussions about Northern Ireland have been endless and often ill-tempered. The failure to resolve the difficulties has poisoned the day-to-day functioning of the UK’s new trading relationship with the EU and effectively blocked any attempts to bring the two sides closer together. This analysis will look at the origins of the current situation (the ‘what’), the specific issue of the Brexit trilemma (the ‘why’), and how matters might be addressed (the ‘how’).

Analysis

The Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP), signed by the UK and the EU as part of the Withdrawal Agreement in 2020, has become the thorniest issue in the new relationship between the two sides. In the run up to the 2016 referendum there was almost no consideration, let alone discussion, of the implications for the Northern Ireland peace process that a Brexit vote might have. Since 2020 the discussions about Northern Ireland have been endless and often ill-tempered. The failure to resolve the difficulties has poisoned the day-to-day functioning of the UK’s new trading relationship with the EU and effectively blocked any attempts to bring the two sides closer together. This analysis will look at the origins of the current situation (the ‘what’), the specific issue of the Brexit trilemma (the ‘why’), and how matters might be addressed (the ‘how’).

The ‘what’

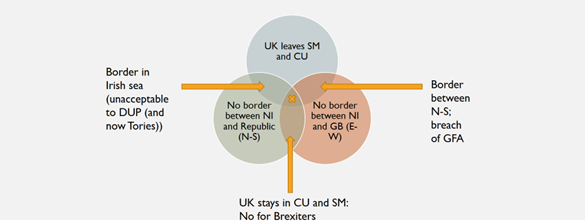

Northern Ireland is in a unique position. It is the only part of the UK with a land border with the EU (on the island of Ireland). And that land border is highly sensitive. Some terrible events occurred in Newry and (London)Derry, both border towns, during the troubles in the 1970s. The great achievement of the Good Friday Agreement, signed almost 25 years ago on 10 April 1998, was that it gently rubbed out that border, de-dramatising and de-politicising it. This was obviously helped by the fact that both the UK and Ireland were members of the EU’s Single Market, meaning effectively open borders for goods and people moving between the North and the South and the Customs Union, so that customs checks would not be necessary. Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU in the 2016 Brexit referendum, although the main political party, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), called for a leave vote. And when the UK as a whole did vote, by a slim majority, to leave the EU a solution had to be found for Northern Ireland. This led to what became known as the Brexit trilemma (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Brexit trilemma

The ‘why’

Under the Brexit trilemma, it was only possible to have two of the following three:

- The UK leaves the EU’s Single Market (SM) and the Customs Union (CU).

- No hard border between Northern Ireland (NI) and The Republic of Ireland (referred to as ‘no North-South border’).

- No hard border between Great Britain (GB) and Northern Ireland (NI) (referred to as ‘no East-West border’).

Theresa May, when Prime Minister, explored the UK as a whole remaining in the EU Customs Union and keeping the UK aligned to the EU’s rules on goods until some other solution could be found, possibly involving the use of technology. This would have avoided a hard border N-S and E-W –points (2) and (3)– but sacrificing point (1) (leaving the single market and the customs union). However, her proposals were unacceptable to the Brexiteers, led by Boris Johnson, who wanted the freedom to do international trade deals (not possible if the UK stayed in the EU’s Customs Union when the UK would still be bound by EU trade deals) and the freedom to de-align from EU rules (a ‘Brexit’ opportunity) which meant leaving the single market. They therefore prioritised point (1) of the trilemma over the other interests.

So, when he became Prime Minister, Boris Johnson insisted that the UK would leave the SM and the CU –point (1) of the trilemma–. Both the EU and the UK agreed that, in order to respect the essence of the Good Friday Agreement, there should be no N-S border –point (2) of the trilemma–. This meant that Northern Ireland would stay in the EU’s Customs Union and the EU’s single market for goods. This also meant that the UK committed Northern Ireland to dynamic regulatory alignment (ie, keeping up to date with) the EU rules in the 300 or so areas listed in Annex 2 to the Protocol, even though the EU would have no say over those rules. Both sides also agreed that, since the EU law was being applied, the Court of Justice had jurisdiction over Northern Ireland in respect of Protocol matters. Both sides also agreed that NI would also stay in the newly created UK internal market too. This meant it would have a foot in two camps (EU and UK); for some investors this proved attractive.

With agreement that the UK would leave the single market and customs union –point (1) of the trilemma– and that there would be no hard N-S border –point (2) of the trilemma– that meant there would be a hard W-E border, ie, down the Irish sea since there had to be checks on goods going into Ireland and thus into the EWU’s single market. Boris Johnson famously denied this was the case but the impact assessment accompanying the legislation implementing the Withdrawal Agreement into UK law made abundantly clear that there would be some paperwork (W-E) and many more checks and paperwork on GB goods going E-W because those goods were at risk of going into the EU’s single market. Although Arlene Foster, then leader of the DUP, declared Boris Johnson’s deal to be a ‘sensible way forward’, it subsequently became clear that her party did not agree. They thought it was unacceptable that there should be checks on goods moving from one part of the UK to another. Their position has hardened to say that they will not re-join the power-sharing agreement needed to get Stormont (the Northern Ireland Assembly) up and running until the Northern Ireland Protocol is abandoned.

Meanwhile, the two men responsible for negotiating the Withdrawal Agreement, Boris Johnson and Lord Frost, started to reject their own deal. The grace periods, designed to soften some of the edges of the introduction of a hard W-E border were unilaterally extended by the UK; the EU responded by issuing enforcement proceedings against the UK, which would ultimately have ended up before the Court of Justice. This further antagonised Lord Frost, who published a White Paper in July 2021 advocating a wholescale reform of the NIP, including the removal of the role of the Court of Justice. This antagonised the EU, which considered the UK to be reneging on its international obligations, concerns already raised by last minute additions to the United Kingdom Internal Market (UKIM) Bill which intended to give UK Ministers powers to renege on key provisions under the NIP, including those on state aid. These clauses were ultimately abandoned before the Bill was enacted but they showed that the UK was prepared to break international law to achieve what it wanted over the Protocol.

Meanwhile, in Northern Ireland, some businesses were benefitting from NI’s unique position part in the EU’s single market and also in the UK’s own internal market. Others struggled due to the inability to obtain key products, notably garden centres. There was also a serious issue in respect of veterinary medicines. Domestic politics also haunted the scene. In the Northern Ireland Assembly elections in May 2022, the Nationalist Sinn Féin gained the largest number of seats; the DUP refused to enter the power-sharing arrangement agreed under the Good Friday Agreement; the Northern Ireland Assembly did not –and continues to not– sit. The timetable for elections has been delayed to see if it is possible to find some solution to the NIP issues.

In Westminster, Boris Johnson –already in considerable personal difficulties, particularly over ‘partygate’– was forced to stand down as Prime Minister in July 2022. Liz Truss, who as Foreign Secretary had made more positive overtures to the EU about Northern Ireland, saw her chance to become Prime Minister. Having been a prominent Remainer in the referendum she needed to burnish her credentials with the Tory right (composed mainly of ardent Brexiteers); she tabled the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill (NIPB) in June 2022 as a way of doing just that.

The NIPB is a legally sophisticated piece of legislation, not least because of the tools used to turn off the conduit pipe by which the NIP can be invoked in the UK by individuals and companies. It also gives Ministers (exceptionally wide) powers to introduce provisions on creating green and red channels to reduce checks, giving businesses the choice of placing goods on the market in Northern Ireland according to either UK or EU goods rules (‘the dual regulatory regime’), ensuring Northern Ireland can benefit from the same tax breaks and spending policies as the rest of the UK and ‘normalising governance arrangements so that disputes are resolved by independent arbitration and not by the European Court of Justice’.

The UK says ‘These changes are designed to protect all three strands of the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement, including North-South cooperation, and support stability and power-sharing in Northern Ireland. They will provide robust safeguards for the EU Single Market, underpinned by a Trusted Trader scheme and real-time data sharing to give the EU confidence that goods intended for Northern Ireland are not entering its market. The legislation also ensures goods moving between Great Britain and the EU are subject to EU checks and customs controls’.

The ‘How’

However, this Bill also represents a fundamental breach of the commitments entered into by the UK under the NIP. The government has justified this breach by reference to the necessity provision of Article 25 of the International Law Commission’s draft article on state responsibility. This enables the state to act to safeguard an essential interest against a grave and imminent peril. Most lawyers do not think the conditions of Article 25 have been made out. Nevertheless, the government pushed ahead with its legislation and it passed its Commons stages before the summer. It is now being considered by the House of Lords, although the timetable has slowed. If the Bill is approved it is likely that the EU will take retaliatory action against the UK, including suspending the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), with the risk of a trade war. Certainly, all cooperation with the EU over matters other than the war in Ukraine has ground to a halt, notably the UK’s desire to join the Horizon programme. The UK has started the dispute process under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement on this issue. As one British official put it to the Economist, ‘[The dispute over the NIP is] like having something in your eye… You can’t focus on anything else’.

In the meantime, Liz Truss got her wish to become Prime Minister but her tenure was exceptionally short and precipitated a major economic crisis. After 44 days in power she was replaced by Rishi Sunak. Sunak has always been a Brexiteer but he is also seen as more of a pragmatist. He seems to want to sort out the problems with the NIP and move on. His Foreign Secretary, James Cleverly, also a Brexiteer, is also more pragmatic and has a warmer relationship with his opposite number in the European Commission, Maroš Šefčovič. Two hardcore Brexiteer and members of the European Research Group, Chris Heaton-Harris and Steve Baker, hold key positions in respect to Northern Ireland. The Americans, too, are now applying considerable pressure on the UK and the EU to reach an agreement; US President Joe Biden wants to come to the UK in April 2023 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement.

Some of the signs are much more promising. The UK has agreed to share real-time data with the EU so that the latter can monitor the flows of goods into Northern Ireland and on into EU territory. Border Control Posts, necessary for inspecting animal and animal products, are also to be built. The distance between the UK and the EU over the introduction of red/green channels (what the EU calls ‘express lanes’) is not so great. The dual regulatory model, proposed by the UK, may be quietly dropped, not least because there are signs that it may itself create tensions between the two sides. The mood music is much better and there is now talk of the two sides entering the ‘tunnel’, possibly as soon as this week, where detailed negotiations can take place away from the glare of publicity.

But the major stumbling block continues to be ‘governance’ and, more specifically, the role of the ECJ. The UK’s Northern Ireland White Paper talked about resolving disputes via ‘independent arbitration’ and not by the ECJ. In other words, the UK wants any disputes over the NIP to be resolved using the WTO-style dispute resolution mechanism found in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement. So long as EU law has a role to play in Northern Ireland this will never be acceptable to the EU. However, more moderate voices suggest, as an alternative, using the dispute resolution mechanism found in the Withdrawal Agreement itself, which has a political phase, followed by an arbitration panel that could refer matters of EU law to the Court of Justice. This route puts a clear political stage into the dispute resolution process.

However, such a compromise has its problems. On the EU side, it has no mandate to make such a fundamental change to the NIP, although it is possible for an agreement to be reached and for a mandate to be secured later. On the UK side, such a solution does retain a role for the Court of Justice, albeit a reduced one. For Brexiteers this is not good enough. As one put it, no sovereign state should be controlled by the ECJ. The DUP too is becoming concerned about what it is hearing. It says that even if the UK gets a deal, it is content with ‘they might still want to see it in operation before they agree to it’. None of this fits well with the April 2023 timetable.

Conclusions

Despite Boris Johnson’s 2019 manifesto commitment to ‘get Brexit done’, Brexit remains far from ‘done’. The issues over the NIP show this all too clearly and the more discussion there is over the Protocol, the more delay there is in improving the thin TCA, which might make the trading relationship between the UK and the EU somewhat better. With the passage of time, the promises made by Brexiteers in 2016 about a better Britain post-Brexit are being sorely tested. The much-vaunted trade deals have produced little: the much prized one with the US has gone nowhere. The two new ones, with Australia and New Zealand, might lift GDP by 0.08% and 0.03% respectively. Meanwhile, UK GDP has taken around a 5% hit as a direct result of Brexit. Some commentators are beginning to express their concerns openly. Now Brexit was, of course, not just about economic and free trade deals; it was about political control. But as the cost-of-living crisis continues to rock many families, the National Health Service (NHS) is struggling in the face of a huge surge in demand (waiting lists exceed 7 million), while the promise on the side of the Leave bus to give £350 million a week to the NHS seems empty. Resolving the NIP issue would have the advantage of starting to normalise relations with the EU and take Brexit off the front pages. It now requires political courage by the Conservative leadership to deliver this.

Image: Map of ireland and united kingdom. Photo: Tom3cky.