Theme: This paper looks at the main causes of dissension and the preferences of the EU’s Member States that must be solved by the Cypriot Presidency in order to reach an agreement on the MFF 2014-2020 by the end of the year.

Summary: This analysis looks at main issues in contention, in addition to the proposals of the leading players to show the current state of the negotiations and the challenges facing the Cypriot EU Presidency, whose aim is to reach an agreement on the multiannual financial framework (MFF) for 2014-2020 during the semester. The authors aim to provide an insight into the complex negotiations surrounding the MFF 2014-2020, although it draws short of presenting the entire range of measures linked to the policy proposals for the new MFF.

Analysis: The Eurozone crisis has made budgetary issues the focal point of political and public debate about the EU. However, public debates on transfers from national budgets to European bailout funds have distorted the public perception of the EU’s financing and spending policies and watered down the image of the Union’s budget as an instrument for growth and employment. Thus the negotiation on the multiannual financial framework (MFF) between Member States has been very much influenced by the discussions on the financial costs of transfers to the EU. The negotiation of the MFFs has traditionally been highlighted in both academic literature and the media as a tortuous battle after which agreements are only reached at the last minute. Since the EU budget accounts for roughly only 1% of its GNI, the question is: why so much political drama? In fact, the negotiation of the MFFs is more than a purely financial discussion about budgetary costs and benefits for the different Member States because it determines the EU’s financial resources and policy priorities for several years. In this respect, the MFFs combine three complex elements: (1) the debate on the budget year; (2) the policy goals involved; and (3) the institutional influence of the various players in the decision-making process.

The negotiation of the multiannual financial framework 2014-2020 (MFF 2014-2020) formally started in June 2011 with the presentation of the European Commission’s proposal ‘A Budget for Europe 2020’.[1] Since then, the negotiation has involved different players –the European Commission, the European Parliament and the Council– as well as different institutional levels –working parties, high-level groups, the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER), different Council configurations and the European Council–. So far, there have been agreements on low-level issues, but the high level issues –such as agriculture payments and cohesion policy– have barely been discussed.

The euro crisis and the cleavage between Member States on the budgetary stimulus for growth and national cutbacks have affected the ongoing negotiations. The perceived decline in public support for the EU has added further tension, in addition to the fact that the Member States to be most affected by the crisis are those that have for decades been receiving structural support from the EU budget.

Nevertheless, aside from the pessimistic context and the contentious nature of the ongoing debate, there seems to be some common ground between the Member States to work towards a MFF 2014-2020 which contributes to growth and employment in line with the EU 2020 Strategy. If this common understanding materialises this would not only be a major step to convert the budget to an instrument to overcome the crisis but also change the nature of the communitarian budget.

This analysis looks at main issues in contention, in addition to the proposals of the leading players to show the current state of the negotiations and the challenges facing the Cypriot EU Presidency, whose aim is to reach an agreement on the MFF 2014-2020 during the semester. The authors aim to provide an insight into the complex negotiations surrounding the MFF 2014-2020, although it draws short of presenting the entire range of measures linked to the policy proposals for the new MFF.

The State of Negotiations

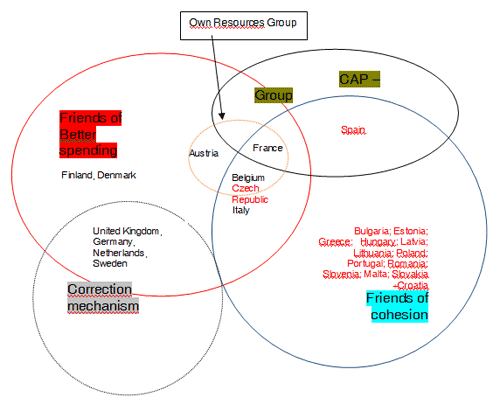

During the past few months the Polish and Danish EU Presidencies have attempted to bring the Member States’ positions closer, but they remain divided on several key elements of the European Commission’s proposals.[2] The discussion is still primarily focused on the overall size of the MFF 2014-2020 as well as on the decisive questions of CAP reform and the future Cohesion Policy. Two broad groups of opinions can be identified: the ‘Friends of Cohesion Policy’[3] and the ‘Friends of Better Spending’.[4] Although both groups agree that the EU should primarily direct its efforts towards measures which contribute significantly to sustainable economic growth and employment, the former focuses on the fact that the EC’s budgetary proposal is the bare minimum for the task. The latter group insists on the need of limiting public spending and considers that the quality of expenditure is the key to generating additional growth.

Despite this conflict, the idea that the MFF 2014-2020 should play an important role in stimulating growth appeared to be gaining traction.[5] During the European Council at the end of June, Member States adopted the ‘Compact for Growth and Jobs’ which will reallocate €60 billion of unused structural funds and €60 billion of capital of the European Investment Bank for fast-acting growth measures.[6] In addition, the Member States stated in the Council’s conclusions that the EU budget must become a catalyst for growth and job creation across Europe.[7]

However, already at the General Affairs Council on 24 July 2012 the consensus seemed to have disappeared and the two groups were confronting each other again. During the General Affairs Council the European Commission presented the revised proposal for the MFF 2014-2020 which includes the accession of Croatia as well as the most recent economic data. While the Friends of Cohesion Policy disapproved of the revised proposal as inconsistent with the message of the European Council, the Friends of Better Spending criticised the proposals for being based on over-optimistic economic forecasts and being over-generous.

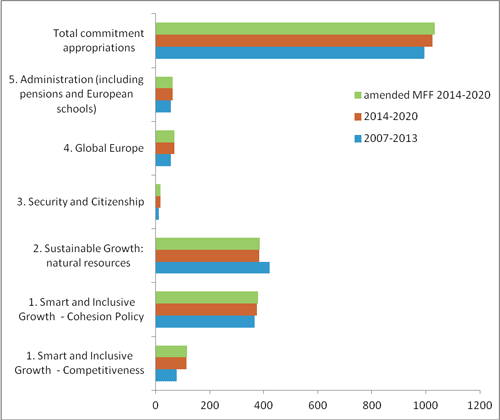

Graph 1. The MFF 2007-2013, the original MFF 2014-2020 and the updated proposal (in € mn, all in 2011 prices)

Source: the authors, based on COM(2012) 388 final; COM(2011) 500.

After taking over the EU Presidency, the Cypriot government held a series of bilateral meetings with Member States and presented a revised version of the ‘Negotiating Box’ at the General Affairs Councils on 24 September. Although the ‘box’ does not yet contain any figures for an expenditure ceiling or for spending headings, the Presidency already considers that the proposal of the Commission will ‘have to be adjusted downwards’.

After the European Council of 18-19 October, the Presidency will release a fully-fledged MFF ‘negotiating box’ with figures on the overall size and for individual headings. In addition, President Van Rompuy will start with bilateral talks at the beginning of November in order to prepare the ‘endgame’. Moreover, at the end of October the European Parliament is expected to adopt its revised position. Despite this tight schedule, the Member States expressed their willingness to reach an agreement at a special European Council scheduled for 22-23 November dedicated solely to the MFF 2014-2020. However the final agreement should, at the latest, be achieved during the European Council of 13-14 December in order to allow the Commission to prepare the 2014 budget in January 2013. If no agreement is reached by the end of 2012, the 2013 ceilings will be extended to 2014 with a 2% inflation adjustment (TFEU, Art. 312,4).

Players’ Preferences (1): The European Commission and the MFF 2014-2020 Proposal

The publication of the European Commission’s proposal sets the starting point for the negotiations. As in previous negotiations the proposal’s structure and content have implications for the way in which Member States develop their positions.

In general terms, the proposed structure and duration of the MFF 2014-2020 are a continuation of the MFF 2007-2013. The EC tried to accommodate the austerity demands of some Member States in order to maintain a certain influence in the negotiation process and to avoid the risk of a stalemate. However, the proposal also included insights from the budget review as well as initiatives from the EP. In this regard, the EC proposed several innovative elements and changes to the ‘rules of the game’ on budgetary decision-making. The main novelties in the proposal can be summarised as follows:

- Concentration on key policy priorities, above all those of the EU2020 Strategy, in order to prioritise spending on growth and employment policies to counter the EU’s economic crisis.

- EU spending should clearly offer ‘European added value’, meaning that there is a general budgetary constraint and choices have to be made.

- Simplification-reduction of instruments and of the administrative burden, especially as regards structural funds and research and innovation funding.

- Introduction of ex ante and ex post conditionality in regional policy, thus linking the use of structural funds to national budgetary management and the fulfilment of the Stability and Growth Pact objectives.

- Flexibility within and across budgetary headings in response to a now traditional demand from the European Parliament.

- An own-resource system based on a Financial Transactions Tax (FTT) and a reformed Value Added Tax (VAT): this is a major innovation in the proposal and tries to give the EU budget a greater autonomy and a new source of income that is not linked to national GDPs.

- Enhanced use of innovative financial instruments (public-private partnership and the European Investment Bank) in areas such as research and innovation and structural funds.

With regard to the overall ceiling, the Commission proposed an amount for the following seven years of €1,025 billion in commitments (1.05% of the EU’s GNI) and €972.2 billion (1% of the EU’s GNI) in payments. This is a 5% increase in the EU budget with respect to the MFF (2007-13) and is an optimistic proposal compared with the evolution of national budgets, subject to strict compliance with the restrictions of the Stability Pact and the new Treaty on Fiscal Discipline.

Regarding the specific spending headings, although all of them have been subject to dynamic reforms in the past decades, the two largest –the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and Cohesion Policy– are again the most debated topics and continue to concentrate most of the funding. Heading 3 (Security and Citizenship), heading 4 (Foreign affairs) and heading 5 (Administration), with smaller amounts, are less problematic.

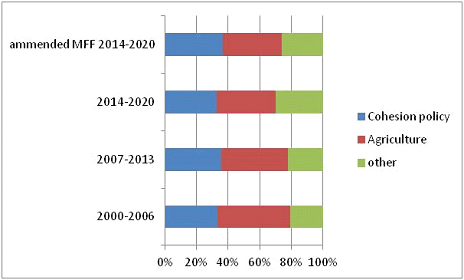

Graph 2. Evolution of spending headings in relation to the total MFF (in %)

Source: the authors, based on COM (2011) 500.

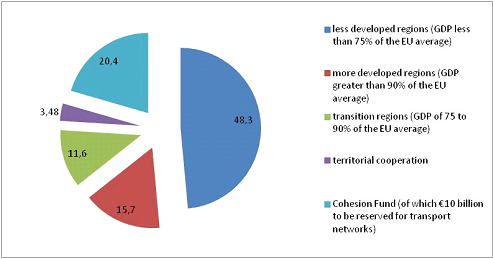

As regards Cohesion Policy, the EC proposed €376 billion, including €40 billion reserved for a future infrastructure fund, earmarking the objectives for the EU2020 Strategy and the creation of a new ‘transition region’ category. In order to ensure that the reformed CAP contributes to the goals of the EU2020 strategy, the EC proposed a stronger conditionality of direct payments to farmers on environmentally supportive practices, the capping and convergence of direct payments and the inclusion of the second pillar of the CAP –rural development– in a common strategic framework, together with the Structural Funds. The share for the CAP of the total budget will be reduced from 41% to 36%, showing the priority given to the €80 billion for Research and Innovation –Horizon 2020– which will concentrate on areas that can stimulate economic growth and competitiveness, such as health, food security and the bio-economy, energy and climate change.

Graph 3. Allocation of resources for Cohesion Policy in %

Source: the authors, based on COM (2011) 500.

The Commission has also proposed increasing the resources for its external action to €96 billion, following the creation of the External European Action Service, and will focus on four policy priorities: enlargement, neighbourhood, cooperation with strategic partners and development cooperation, including a new Partnership Instrument replacing the Industrial Cooperation Instrument. The main differences with the current framework are primarily policy principles: differentiation, conditionality and concentration as well as the renewed attempt to achieve a greater simplification.

Regarding administrative expenditure, the EC proposes a 5% reduction in the staff of each institution, as well as measures to increase efficiency.

Players’ Preferences (2): The European Parliament

The Treaty of Lisbon gave the European Parliament (EP) more power as regards to the MFF (TFEU Art. 312). It is a fundamental change compared to the previous negotiations because Member States have to take into account the decision of the EP before reaching a final agreement. The experience of the first two years of the Treaty has also shown the enhanced political role of the EP in the annual budgetary negotiations.

In the MFF 2014-2020the EP has been one of the major players from the very beginning of the current negotiation process:

- It did not wait for the Commission’s proposal before presenting its own position.

- It prepared position papers on contentious issues in accordance with the Council’s negotiation steps.

- Its representatives meet the Trio Presidency ahead of the General Affairs Council.

- It is increasingly the contact point on a day-to-day basis for the national parliaments and at common conferences.

Traditionally, the European Parliament has an incentive to propose expenditure programmes. In practice, however, differences in the incentives for Member States and the EP have been reduced. On the one hand, there is a growing acceptance among MEPs of an austerity approach towards budgetary decisions and, on the other, the interests of individual Member States in specific expenditure headings coincide with those of the EP. In this respect the definition of a common position on specific spending headings, eg, the Cohesion Policy, is increasing in complexity.[8] In the same way, with regard to CAP reform, MEPs have submitted more that 7,000 amendments to the draft proposals for reform,[9] and the Agriculture Committee will have to work hard to find a common position which has to be voted on by the end of November.

Nevertheless, an overwhelming majority of MEPs approved the report of the Special committee on the Policy challenges and budgetary resources for a sustainable Union after 2013 (SURE). It called for an increase of at least 5% over the 2013 budget for the next MFF, which would raise the size of the budget to 1.1% of the EU’s GNI. According to the EP this would not imply an additional burden for the Member States. The EP voted on 23 May 2012 on a resolution in favour of a FTT as a measure to generate additional own resources for the EU budget.

The resolution underlined that the EP will not give its consent to the MFF without a political agreement on the reform of the own-resources system. In addition, a further resolution on the MFF 2014-2020 which called for more flexibility for shifting funds between the different areas of expenditures as well as between fiscal years was adopted by an overwhelming majority in June 2012.

Players’ Preferences (3): The Presidency

The mediation provided by the EU’s Presidency is indispensable for finding compromises and for the final package deal. Adopting a ‘European’ hat, Presidencies keep the negotiations moving at various institutional levels and present compromise options on contentious issues at critical moments in the negotiation. While the Polish EU Presidency pursued a ‘bottom-up’ philosophy in order to improve the understanding of the individual negotiating positions, the Danish EU Presidency assumed a more proactive approach and presented during its term different versions of the ‘negotiating box’. Experience shows that small Member States make for good EU Presidencies, since they are cautious in their external behaviour, acting as honest brokers. However, so far no small country has been able to reach an agreement on a MFF. It has always been the bigger Member States that can subordinate certain national material interests to the benefit of reaching an agreement.[10] During the negotiation of the MFF 2007-2013, the Luxemburg Presidency failed to achieve an agreement and only the UK Presidency managed to reach it by accepting a reduction in its ‘rebate’. Finally, the recently elected Chancellor Merkel helped with some additional resources to reach the package deal.

Whether Cyprus, which is hosting its first Presidency, manages to fulfil these expectations and its own ambitions remains to be seen. Several observers consider that its limited administrative resources, its current minority government and fragile economic situation are not the best conditions for a successful EU Presidency.[11] Nevertheless, Nicosia confirmed its ambition of reaching an informal agreement at the October European Council, a deal with the European Parliament in November and a final agreement in December. In 2013 Ireland will assume the Presidency, again a small country but experienced in chairing the Council.

Players’ Preferences (4): The Member States

Member States receive different amounts of financial resources from specific headings of the EU budget and contribute to its financing. Although these national financial balances or net returns do not reflect the benefits of EU integration, EU member states traditionally concentrate primarily on these zero-sum terms in order to determine their negotiating positions.

The bargaining power of Member States and the unanimity rule, according to which any Member State can block the final agreement, determine the outcome of the intergovernmental negotiations. Within this context the top one or two priorities of each Member State have to be accommodated as far as possible, no matter the size of the country. Nevertheless, in the EU-27 coalition building has become more important. As already mentioned, two broad groups can be identified: the ‘Friends of Cohesion Policy’ and the ‘Friends of Better Spending’. Although the names have changed both groups represent the traditional division between net payers and net recipients. In addition, both groups (with the exception of Italy) also reflect the existing cleavage between Member States on EU anticrisis measures.

With regard to the ‘Friends of Better Spending’, already in December 2010, the UK, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Finland sent an open-letter to Commission President Barroso demanding an increase of the MFF 2014-2020 below the rate of inflation. Since then, around 10 Member States claim the same austerity for the MFF 2014-2020 as the one applied at the national level, as well as a concentration on ‘better spending’ for ‘smart growth’.

During the General Affairs Council on 24 April a group of seven Member States signed as the ‘Friends of Better Spending’ a non-paper reiterating their demands for a limitation of public expenditure at the European level[12] and a concentration of their impact in order to reach sustainable growth and the economic governance objectives. In addition, the spending of EU funds should be planned, programmed, controlled and evaluated in a more efficient way.

Similar concerns were raised on the amended MFF 2014-2020; the group claimed that it was still inconsistent with the current economic crisis and Member States’ fiscal consolidation efforts. The ‘Friends of Better Spending’ represent those countries where the debate at the national level is more politicised and where the budget has become an issue of political symbolism. National parliaments such as the Dutch and the British have approved negotiating lines for their governments, dictating a nominal freeze of the budget. In others, such as Germany, debate between citizens and policy makers concerning its role as European paymaster backs the government’s austerity position.

The ‘Friends of Cohesion Policy’ was formed by the new Member States plus Portugal, Greece and Spain in 2004 in order to secure the role of Cohesion Policy in the negotiation of the MFF 2007-2013. The Polish government re-activated the group which presented its first joint Declaration at the General Affairs Council in November 2011, defending the necessary resources for Cohesion Policy and CAP. On 24 April 2012, 13 Member States[13] signed a communiqué in Luxembourg stating that the Commission’s proposal concerning Cohesion Policy is the absolute minimum. At the beginning of June the ‘Friends of Cohesion Policy’ issued a further statement in Bucharest which was already signed by 15 Member States[14] reiterating the important contribution that Cohesion Policy makes in terms of growth and employment.

The ‘Friends of Cohesion Policy’ also took a negative view of the reduction of the Cohesion Policy budget by around €5.5 billion in the revised MFF 2014-2020 and claimed that the revised proposal was ‘not consistent with the message of the [June] European Council’.[15]

Besides the conflict line between the ‘Friends of Cohesion Policy’ and the ‘Friends of Better Spending’, both groups disagree internally over which headings of the budget should be subject to spending restrictions and which heading should be prioritised, as well as how the EU should be financed.

Overall Ceiling: Because of the general austerity debate there is no Member State advocating an increase in the level of the EU budget as foreseen by the EC. However, among the ‘Friends of Better Spending’ there emerged a debate on how much the budget should be reduced. While in January 2012 the UK, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands and Sweden demanded that the Commission’s proposal needed to be reduced by €100 billion, Finland claimed a budget of less than 1% of the EU-27’s GNI.

After supporting the demands for austerity, Italy has recently sympathised with the ‘Friends of Cohesion Policy’. France changed its position after the national elections and together with the Czech Republic did not specify what amount of reduction it was seeking. However, there is a growing number of Member states which demand the inclusion of spending topics which have been placed outside the budget in the MFF structure, such as the emergency tools for agricultural market crises, which could require cuts in other areas.

Cohesion Policy: As we have seen, beneficiary countries try to ensure sufficient funding for Cohesion Policy. In this context, several cohesion countries criticise the new macro-fiscal conditionality proposed. Although the goal of conditionality, as favoured by the group of better spenders, is to punish misbehaviour at the national level, suspending funding will have the most direct negative impact in the regions. Some countries (Italy, Poland, Lithuania and Estonia, among others) called for macroeconomic conditionality to apply to all EU policies, not just in the field of structural funds, rural development and fisheries funds.

The definition of the new category of ‘transition regions’[16] has also been met with scepticism, and several Member States have argued that it would be better to concentrate resources on the regions that are most in need. On the other hand, some French and German regions oppose their governments’ positions and, together with Spain, firmly support the new ‘transition regions’ category.

The ‘Friends of Cohesion’ proposed not to include specific measures in the future Cohesion Policy for Member States with a significant decrease in their GDP between 2007 and 2009.[17] This was criticised by the Spanish government, which only recently committed to this group along with the Czech Republic in June 2012, after the demand was excluded. In addition, cuts in other headings in favour of Cohesion Policy are not supported by all Member States, and neither is the new limit of 2.5% of GDP imposed on structural funds, as opposed to the previous 4% limit.

Furthermore, several Member States, mainly the ‘Friends of Better Spending’, would like to cap spending in Cohesion Policy and create a ‘reversed safety net’ or concentrate structural funds on tackling unemployment, particularly youth unemployment. These proposals could also create tensions in the ‘Friends of Cohesion’.

Common Agricultural Policy: The proposals regarding CAP reform deeply divide Member States. On the one hand, the proposals do not follow the preferences of those Member States (such as the UK, Denmark and Sweden) which are critical of CAP and have proposed to eliminate or substantially reduce direct aid. On the other hand, the proposals have not been welcomed by traditional beneficiaries of CAP like France, Ireland and Spain, which criticise among other things the cuts in overall spending on CAP and that the reform proposals are too far-reaching.

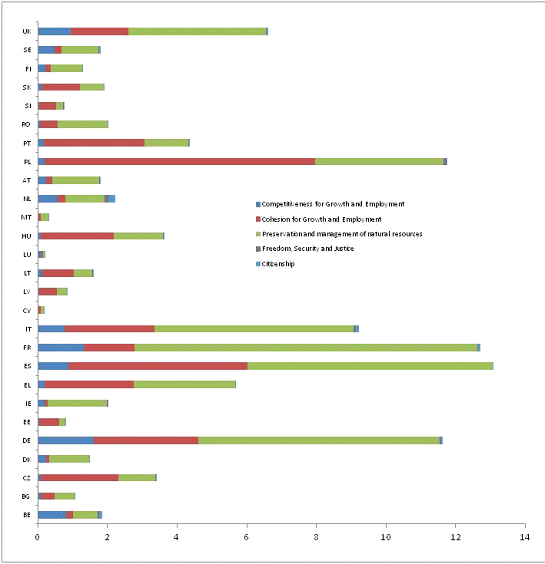

A third group, namely Poland and some other new Member States, demands a much stronger reform of this policy in order to achieve the equalisation of direct payments and fair competition for farmers in the EU market. In 2010 France was the biggest recipient of agricultural funds (18%), with Germany and Spain occupying second place (each receiving 13% of agricultural expenditure).

Graph 4. Funds received by Member States by spending headings, 2010 (in € bn)

Source: the authors, based on: http://ec.europa.eu/budget/index_en.cfm.

Research and Innovation: Apart from some discussions concerning the transfer of certain projects out of the main headings of the MFF, such as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, Member States tend to be generally satisfied and recognise the advantages of the public-public and public-private partnering instruments put forward in the Commission’s proposal. Some contentious points are related to the new financing rules proposed by the Commission. In addition, some Member States criticise assignations based exclusively on excellence and demand criteria which can help build the capacities needed to compete with Member States who are traditionally successful in the European R&D programmes, thus promoting a ‘technological convergence’ in the EU.

External Action: In general terms, the proposal to differentiate and concentrate external spending has also been welcomed by the Member States. A key priority for Member States, the EC and the EP is to respect the commitment to devote 0.7% of GNI to the fulfilment of the Millennium Goals. Enlargement and the ENP are further priorities. Nevertheless, Member States which are giving priority to specific headings (like PAC or Cohesion Policy) would probably argue that the cuts be made elsewhere, such as heading 4. Moreover, Member States which advocate a reduction of the EU budget would accept cuts in Heading 4 in order to get a final agreement. In addition, we can expect a strong discussion on the question of which specific regions will receive financial support and on how the new policy principles for the EU external actions will be put into practice. The Spanish government already argued that there should be an increase in funds for Latin America, and expressed concern over the fact that the MFF 2014-2020 will exclude bilateral agreements with 11 countries in Latin America.

Administration: While several Member States –Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden– demanded additional cuts in Heading 5, Belgium, Luxemburg and Poland support the Commission’s proposals.

EU Own Resources: Almost all Member States agree that the own-resources system needs to be reformed; nevertheless, the question of how reform should be carried out is highly controversial. France, Belgium, Greece and Austria are in favour of the introduction of a Financial Transactions Tax and consider allocating a portion of its revenue to the EU budget. France, especially, has taken the lead in demanding new own-resources in order to ensure coherence between the EU budget’s ambitions and capacities. Germany is also in favour of the introduction of a FTT but would like to collect it by itself and continue with the GNI-based resource. The UK has already firmly rejected all proposals regarding new own resources.[18]

With regard to the system of correction mechanisms, the EC proposes to replace all corrections mechanisms by a system of fixed annual lump sums when the contribution is excessive compared to relative prosperity. This proposal is mainly rejected by the UK, which is the main beneficiary of the current British rebate. Other Member States (Spain and new Member States) consider that corrections are not justified.

Graph 5. Member States positions on the MFF 2014-2020

Conclusions: This paper looks at the main causes of dissension and the preferences of the EU’s Member States that must be solved by the Cypriot Presidency in order to reach an agreement on the MFF 2014-2020 by the end of the year.

We conclude that the MFF 2014-2020 continues the logic of previous negotiations, according to which Member States are unwilling to go beyond small incremental changes in the structure of the EU budget. Although both CAP and Cohesion Policy have been internally deeply reformed, they remain the most important spending headings and represent the most important issues on the agenda. In this respect, the current negotiation also reflects the long-standing cleavages inherent in the logic of the budget structure. Since no Member State wants an increase in the EU budget, the question for the months to come is where to cut spending.

There are strong positions regarding Cohesion Policy and CAP and cuts in spending on external action or even on Competitiveness are very likely in order to reach a final agreement.

With regard to policy goals, all players agree on increasing the conditionality of spending and link it to the fulfilment of the objectives of the EU 2020 Strategy, as well as to the use of the European budget as a tool to stimulate job creation and growth and in areas where the EU can deliver added value. However, there is no consensus on how to stimulate job creation and what constitutes European added value.

Although an increasing percentage of spending is earmarked for the fulfilment of the EU2020 Strategy the EC has not presented a revolutionary new budget and the proposal reinforces the evolutionary paradigm change in the perception of the EU budget: from a budget aimed at accommodating Member State preferences to an instrument meant to address common European interests.

In relation to the institutional setting, the establishment of a new system of own resources, which would represent a new qualitative step towards the EU’s fiscal autonomy, seems unlikely. In addition, there is no consensus between Member States to give European Institutions more flexibility for shifting funds, according to their criteria, between the different areas of expenditure. Nevertheless, the current negotiation has shown that the EP is assuming a much more proactive and self-conscious role.

It can be concluded that the negotiation of the MFF 2014-2020 is a very difficult task on the Cypriot EU Presidency’s agenda, not least because of the sharp divergences between Member States and the tight schedule. In addition, the EP has already announced a tough negotiation with the EC. Moreover, the Presidency seems to have little elbow room to sacrifice material interests to the benefit of reaching an agreement. The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, who faces re-election in October 2013, has left the door open for a deal to be struck as late as the March 2013 European Council.

Finally, there is no guarantee that the EU budget will become a solid financial instrument to meet the new policy goals, as the MFF specifies only the overall limit for spending headings. The experience of the past two decades shows that annual budget expenditure is systematically lower than the MFF ceilings.[19] In this respect, the annual budgetary negotiations will be increasingly important.

Mario Kölling

Centre of Political and Constitutional Studies

Cristina Serrano Leal

PhD in Economics

[1] COM(2011) 500.

[2] M. Kölling & C. Serrano Leal (2012), ‘Austerity vs Stimulus: The MFF 2014-20’s Role in Stimulating Economic Growth and Job Creation’, ARI nr 24/2012, Elcano Royal Institute.

[3] Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. Italy sympathises with the group.

[4] Austria, Germany, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden.

[5] Remarks by President Van Rompuy following the first session of the European Council, 28/VI/2012.

[6] Member states agreed to increase the capital of the European Investment Bank by €10 billion which will increase the Bank’s overall lending capacity by €60 billion. The other €60 billion comes first from the reallocation of unused structural funds (€55 billion), and from the pilot phase of Project Bonds (€5 billion).

[7] Conclusions of the European Council (28-29/VI/2012).

[8] ‘EU kicks off negotiations over regional funding budget’, Euroactive, 13/VII/2012.

[9] 2,292 amendments to Direct Payments proposals, 2,127 amendments to Rural Development proposals, 2,094 amendments to Single Market proposals and 769 amendments to Finance and Cross Compliance proposals.

[10] Germany 1988; the UK 1992; Germany 1998; the UK 2005.

[11] ‘Journey towards the unknown’, Europolitics, 13/VII/2012.

[12] The non-paper of 24 April signed by Austria, Denmark, Finland, France Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden). France did not sign the non-paper of 29 May. The non-paper of 29 May was signed by Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK.

[13] Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia plus Croatia

[14] Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain plus Croatia.

[15] ‘New proposal worries Friends of Cohesion’, Europolitics, 24/VII/2012.

[16] This category will include all regions with a per capita GDP between 75% and 90% of the EU-27 average.

[17] Friends of Cohesion Policy, Luxemburg a communiqué, 24/IV/2012.

[18] ‘France posing as Zorro of own resources’, Europolitics, 25/VII/2012.

[19] Jorge Núñez Ferrer (2012), ‘Between a rock and the Multiannual Financial Framework’, CEPS Commentary, 27/IV/2012.