Theme

This paper [1],[2] explores whether Argentina’s stabilisation plan is the prelude to an economic take-off, or a mirage destined to fail like previous stabilisation plans. It further highlights the crucial role of an agreement with the IMF, key to transforming the current scheme into an orderly transition to a sustainable model.

Summary

For optimists, the stabilisation plan is bearing fruit after an initial stage of great sacrifices for the population. The stability achieved and a government committed to fiscal balance and a pro-market and pro-investment agenda, added to the possibilities of large investment projects in strategic sectors, put Argentina on the verge of an economic take-off. For the sceptics, the apparently good progress of the economy is a mirage prior to a new devaluation and crisis that will repeat the failures of previous plans.

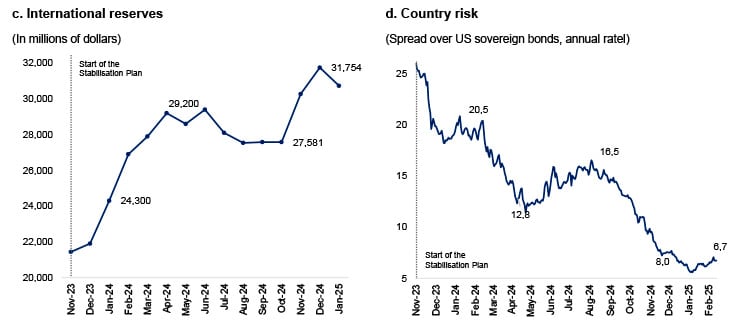

At the centre of the discussion is the so-called ‘exchange rate overvaluation’. Argentina has become very expensive in dollars and, according to the Big Mac index, the Argentine peso is the most overvalued currency in the world after the Swiss franc.

Optimists see this peso appreciation as a sign of success, reflecting an improvement in productivity and an export boom (present and future) in energy, mining and renewables. Sceptics warn that stability is a mirage driven by the carry trade, a financial operation in which investors convert US dollars into pesos to take advantage of very high yields in dollars (currently 19% per annum) for short-term placements in local currency. This unsustainable policy keeps the exchange-rate artificially appreciated, increases international reserves and lowers country risk, generating a false sensation that things are going well. Sooner rather than later, they argue, the ‘financial merry-go-round’ will come to a halt and speculative capital run towards the exit, precipitating a disorderly devaluation and another crisis.

How do we identify whether Argentina is on a collision course or on the way to the promised land? The agreement with the IMF is key to transforming the current scheme into an orderly transition towards a sustainable model. If closed, it would inject international reserves that Argentina badly needs, would allow lower interest rates without capital flight and would consolidate exchange rate stability without relying on the carry trade.

Argentina has already made a fiscal adjustment of 5% of GDP to balance its accounts, cleaned up the BCRA’s balance sheet, implemented a successful capital amnesty programme, and put in place an investment incentive regime and a reform agenda. With IMF support, the country could return to the international capital markets, gradually lift the currency controls and lift the remaining obstacles to attract strong investments in strategic sectors. This would open the door to a period of stability and sustained growth.

It is true that Argentina’s economic history is packed with episodes of boom and bust of failed stabilisation plans. It is also true that, with the achievements already made and with the support of the IMF, this time it may be different.

Analysis[3]

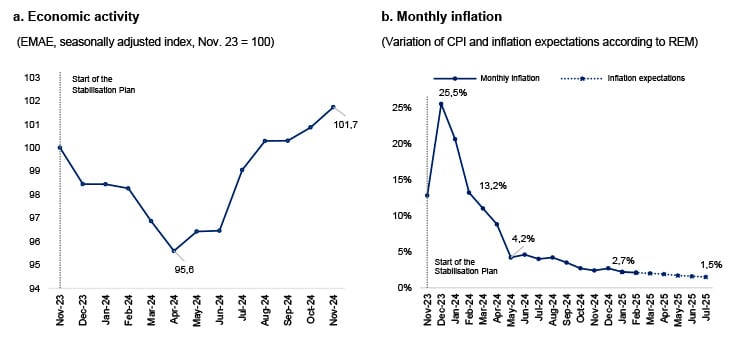

Argentina is at a turning point. For some, the government’s stabilisation plan is bearing fruit after an initial stage of great sacrifices for the population: the exchange rate is stabilising, the exchange rate gap is narrowing, international reserves are recovering and country risk is falling, inflation is receding, and the economy and wages are recovering (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The macroeconomic outcomes of the Milei plan

With a government committed to fiscal balance and a pro-market and pro-investment agenda, and the possibility of developing large investment projects in strategic sectors, the country could be on the verge of an economic take-off.

For others, however, this stability is a mirage prior to a new crisis. Argentina has gone many times through stabilisation plans that seemed to be successful until they collapsed, the Convertibility Plan being the most recent one. According to this view, the current scheme is unsustainable and will end in abrupt devaluation and crisis.

Faced with this dilemma, the question is inevitable: is Argentina on a collision course or on the way to the promised land?

1. Collision course or on to the promised land?

At the centre of this discussion is the appreciation of the real exchange rate or ‘exchange overvaluation’ as it is known in Argentina. Argentina has become much more expensive in dollars since the beginning of the plan: more than 100% if the blue dollar is taken as a reference, and 56% if the average between the official dollar and the blue dollar is taken (see Figure 2). According to the ‘Big Mac index’ published by The Economist as an informal indicator to assess whether currencies are overvalued or undervalued by comparing the price of a Big Mac hamburger in different countries, the Argentine peso is the most overvalued currency in the world after the Swiss franc. Those who have visited Argentina recently have witnessed the rise in domestic prices in dollars.

This is how the discussion between optimists and sceptics is schematically posed.

Figure 2. Exchange rate ‘overvaluation’ in Argentina

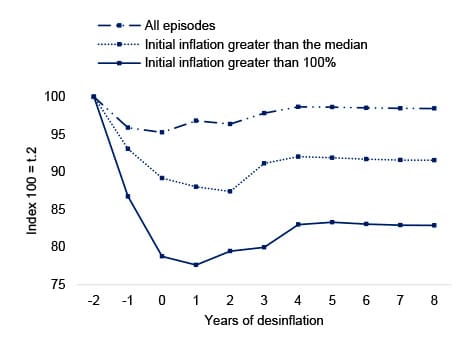

Optimists see the peso appreciation as a sign of success. The history of other successful stabilisation plans supports this view: those that managed to reduce the inflation rate to single digit levels have been preceded by a significant real appreciation of the exchange rate, especially those that started with inflation rates above 100% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The paths of the real exchange rate

According to this view, fiscal balance, stability, structural reforms and investment incentives increase productivity and attract capital to develop projects in strategic export sectors (energy, mining, renewables and agribusiness). Higher productivity and a thriving export sector leads to a natural appreciation of the exchange rate. Moreover, once the exchange restrictions that limit the purchase of foreign currency (the so-called cepo) are lifted and Argentina returns to the international capital markets, investments in strategic sectors that are currently incipient will be transformed into an avalanche and there will be an export boom.

Sceptics, on the other hand, argue that historical evidence also shows that failed stabilisation plans were almost always preceded by a significant appreciation of the real exchange rate. Moreover, many plans that eventually foundered were characterised by an apparent economic improvement, precisely because the plan was inconsistent, and its demise was anticipated. They point out that this apparent improvement is induced by unsustainable factors, such as the carry trade, which could generate a sudden collapse when the flow of speculative capital is reversed.

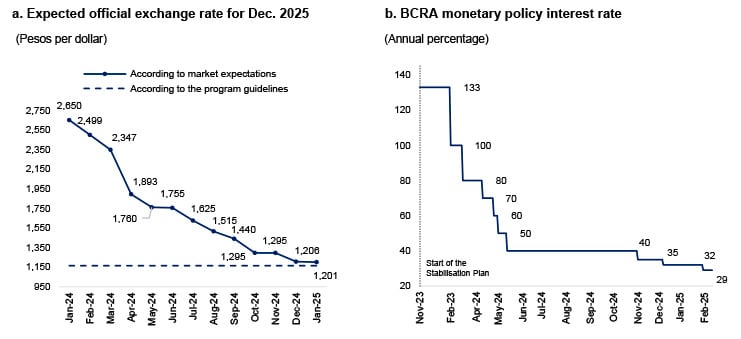

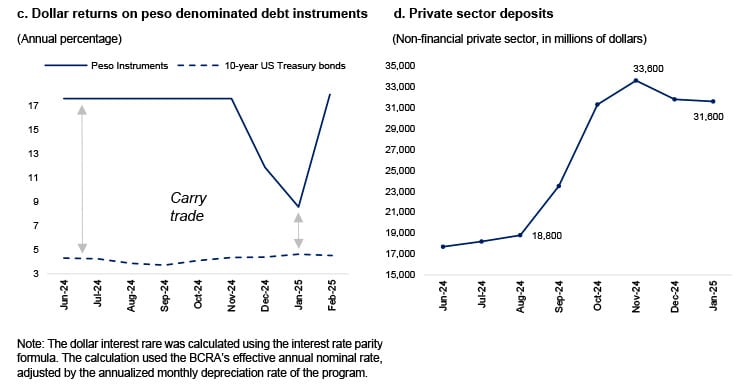

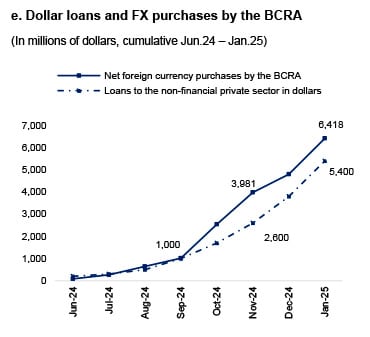

The carry trade is today the main source of doubt about the plan’s viability. It is a financial operation by which investors convert their dollars into pesos and invest them in short-term financial assets in local currency (eg, Treasury Bills) at very high yields. With nominal annual interest rates of 29% and a preannounced devaluation of 1% per month, the expected return in dollars reaches 19% per year, attracting short-term speculative capital (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The carry trade and net dollar purchases by the BCRA

This sale of dollars induced by the expected high yields of local currency instruments generates a transitory demand for financial assets in pesos, keeps the parallel exchange rate artificially appreciated, increases the purchase of dollars and the Central Bank’s reserves, and reduces the country risk, all of which gives a false sense that things are going well.

However, critics warn that the strategy is not sustainable. Interest rates so high in relation to the announced pace of devaluation inevitably lead to fiscal collapse. And its corollary, an artificially appreciated exchange rate, makes local production uncompetitive in export and import-competing sectors (including services, such as tourism).

Sooner rather than later, they argue, the ‘financial merry-go-round’ will come to a halt and speculative capital will run towards the exits, precipitating a disorderly devaluation and another crisis. The artificially appreciated exchange rate (the ‘sweet money’ as this phenomenon is known in Argentina, and which gave rise to a magnificent film by Fernando Ayala) is only the most visible symptom of the programme’s inconsistency.

2. The IMF agreement: the key factor

How can we distinguish, then, whether we are facing one or the other scenario: the ultimate success or an inevitable crisis? Both optimists and sceptics present strong arguments. To reconcile both positions, it is necessary to introduce the time dimension and a key factor: the agreement with the IMF.

The sceptics’ fears could materialise if excessively high interest rates and their corollary, an artificially appreciated exchange rate, were to continue for a sufficiently long period.

And this is where the agreement the government is negotiating with the IMF comes into play, the key to transforming the current scheme into an orderly transition to a sustainable model. An agreement with the IMF, and the inflow of fresh funds to strengthen the reserves position, would allow interest rates to be reduced without generating capital flight, and exchange rate stability could be maintained even without the carry trade. Seen from this perspective, a policy of temporarily high interest rates to buy time, keep the dollar stable, protect international reserves, and consolidate the decline in country risk and inflation, may be an optimal strategy, a transitory bridge towards a post-IMF agreement scenario, with much greater financial leeway.

Unlike other negotiations with the IMF, this one does not seek to control a crisis, but to consolidate a comprehensive stabilisation plan already underway. Argentina has carried out on its own a fiscal adjustment of 5% of GDP to balance public accounts, a clean-up of the BCRA’s balance sheet (transferring interest-bearing liabilities to the Treasury and dismantling contingent liabilities by issuing BOPREAL and repurchasing puts), which has allowed the BCRA to regain the use of the interest rate as an instrument of monetary policy, a capital amnesty programme that resulted in the repatriation of more than US$20 billion (doubling private-sector bank deposits denominated in dollars), and the implementation of a pro-market and pro-investment structural reform agenda, led by the new Ministry of Deregulation and Transformation of the State, together with a regime for the promotion of large investments (RIGI).[4],[5],[6]

However, the country also badly needs external financing to strengthen its international reserves, to gradually lift exchange-rate controls smoothly, and to return to the international capital markets, thus unlocking the remaining obstacles to the arrival of investments in strategic sectors such as mining, energy and renewables, putting Argentina on a path of stability and sustained growth. This configuration would make the optimists’ view viable.

Conclusions

The Argentine stabilisation plan divides the waters between the optimists who see it as the prelude to an economic take-off and the sceptics who consider it as another mirage destined to collapse. Exchange rate stability, the fall in inflation, the strengthening of international reserves and the fall of country risk, the recovery of the economy and wages, are exhibited as achievements by the government and the supporters of the plan, but the spectre of the exchange rate overvaluation and the reliance on short-term speculative capital resulting from the carry trade, feed the doubts of the critics, who maintain that the plan is unsustainable.

In this scenario, the agreement with the IMF emerges as the great turning point: if it materialises and injects the necessary international reserves so that Argentina can return to the international capital markets and gradually lift exchange rate controls, it would allow the reduction of interest rates without generating capital flight, and exchange-rate stability could be maintained even without the carry trade, consolidating the programme and opening the door to a period of stability and sustained growth.

It is true that Argentina’s economic history is packed with episodes of boom and bust of failed stabilisation plans. It is also true that, with the achievements already made and with the support of the IMF, this time it may be different.

[1] The author would like to thank Tomás Sanguinetti for his excellent work as a research assistant in the preparation of this paper. Tomás is an economist from the University of Montevideo (Uruguay) and is currently pursuing a degree in Data Science.

[2] The author would also like to thank Pablo Ottonello, associate professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Maryland, for his excellent comments and suggestions on the first version of this paper. Furthermore, Pablo provided the data for Figure 3.

[3] This analysis is an expanded version of the column published in the Madrid daily El País on 15 February 2025.

[4] Bonds for the Reconstruction of a Free Argentina (BOPREAL) are financial instruments issued by the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) that may be purchased in pesos for importers to regularise outstanding debts for imports of goods and services registered until 12 December 2023.

[5] Put options are contracts that grant the holder the right, but not the obligation, to sell an asset at a predetermined price within a specified period of time. The BCRA issued these instruments so that banks could sell public debt securities to the BCRA in case of liquidity needs or in the event of a fall in the value of such securities. However, the existence of these puts represented a potential source of monetary expansion, since, if the banks exercised their right to sell, the BCRA had to print pesos to purchase the securities. To mitigate this risk and reduce monetary policy uncertainty, the BCRA decided to buy back a significant portion of the puts.

[6] The Incentive Regime for Large Investments (RIGI) is a programme established by Law No. 27,742 in Argentina, aimed at promoting large investments in key sectors such as agribusiness, infrastructure, forestry, mining, oil and gas, energy and technology. It offers tax, customs and exchange rate benefits to projects exceeding US$200 million, providing stability and legal certainty for 30 years.