Theme

The situation on the Korean peninsula remains highly volatile and upcoming events could have a significant impact on the region. The EU and its member states should stand ready.

Summary

It would be both an analytical and a political mistake to believe the situation in the Korean Peninsula is stable and lastingly improved thanks to the diplomatic efforts initiated in 2018. Despite the political stage-setting, the very problems on the Peninsula remain: inter-Korean relations are not improving and agreements reached in both Panmunjom and Pyongyang are not implemented while cooperation and even communications are at a standstill; North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile programmes are ongoing and have significantly strengthened North Korean capacities while negotiations are at a dead-end. The upcoming 2020 US presidential election in November and the 8th Congress of the Workers Party of Korea (WPK) in January 2021 will be two major events shaping the coming events. It is essential for the EU and its member states to be more proactive, and move from a strategy of critical engagement to implementing a strategy of credible commitments.1

Analysis

Typhoon Bavi, which hit the Korean peninsula at the end of August, may only be an omen that after the relative calm of just under three years a storm may be about to hit again. Recent inter-Korean tensions and North Korean declarations could be a preview of what could come in early 2021 in the Korean Peninsula. With a likely new US Administration and a new North Korean national strategy supposedly to be presented next January, the risk of renewed tensions is real , the lack of trust remains an overarching element of relations and the fundamentals that are destabilising the peninsula remain.

While the last few years were marked by relative calm and a partial resumption of dialogue at the highest level –especially compared with the tensions of 2017– it is important to avoid two misapprehensions. The first would be to believe that because of the high-level meetings in 2018/2019 and the exchange of courtesies between leaders, the situation on the Korean peninsula has been permanently stabilised. The truth is quite the opposite. As President Moon expressed at the opening of 21st National Assembly last July, ‘managing inter-Korean and US-North Korea relations is still akin to skating on thin ice’. The second would be to think that because North Korea has not conducted a nuclear test since September 2017 or a long-range ballistic missile test since November 2017, the North Korean nuclear and ballistic missile programs are on hold. On the opposite, the North Korean nuclear and ballistic missile crisis is the most serious proliferation crisis the international community currently face on the world stage.

From moonshine to sunset policy: inter-Korean relations at a standstill

On 16 June, the North Korean authorities demolished an inter-Korean liaison office in the border city of Kaesong. Temporarily closed since 31 January amid fears of the spread of the COVID-19 virus, the office had been opened in 2018 to facilitate dialogue between the two Koreas. Pyongyang violently criticised Seoul, asserting that ‘the south side has systematically breached and destroyed the Panmunjom Declaration, Pyongyang Declaration and agreements between the north and the south while openly doing all sorts of hostile acts including war exercises against the north’.2 While the absence of a military escalation between the two Koreas is to be welcomed, it must be acknowledged that the recent hopes symbolised by the three inter-Korean summits are now a long way off. This deterioration in relations should not come as a surprise for at least three reasons.

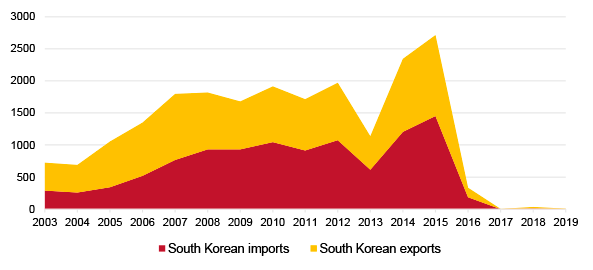

First, there is a growing frustration in both Pyongyang and Seoul since the two main goals –improving inter-Korean relations and denuclearising North Korea– are now fully intertwined because of sanctions, limiting the possibility of the former to be reached without concrete progress with the latter. In the early 2000s, the Sunshine Policy and its successor was an unconditional strategy of engagement, enabling more than 350,000 South Korean tourists to visit Mount Kumgang and inter-Korean trade to reach US$1.8 billion in 2007 despite the first nuclear test in 2006. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, inter-Korean trade was initially partly preserved despite nuclear tests in 2009 and 2013, but in 2016 Seoul decided to close the Kaesong inter-Korean industrial complex while a new set of UNSC resolutions in 2016 and 2017 made any cooperation between the two Koreas much more constrained.3 The recent June incident in Kaesong, which was a direct provocation to South Korea, while calibrated and limited –a very symbolic provocation but on North Korean territory, non-military and not threatening the security of the South Koreans and undoubtedly targeting Seoul and not Washington–, may be only the beginning if by the end of the year the North Koreans consider that Seoul can no longer contribute to the improvement of inter-Korean relations and that Pyongyang has nothing to expect any longer from Seoul.

Secondly, Seoul has no more aces up its sleeves in dealing with Pyongyang and has almost reached the limit of what South Korea can do without violating international sanctions, causing additional tensions in the US-ROK alliance, or bearing too big a political cost. In terms of diplomatic strategy and political communication, the Moon administration played well all the cards it had from sport and cultural diplomacy to inter-Korean summits, from military to military cooperation to railways field surveys, etc. Yet, in 2019, the dynamic stopped brutally. Despite the landslide victory of the Democratic Party and its satellite, the Platform Party, at the 2020 South Korean legislative election last April, there is not much President Moon can do.

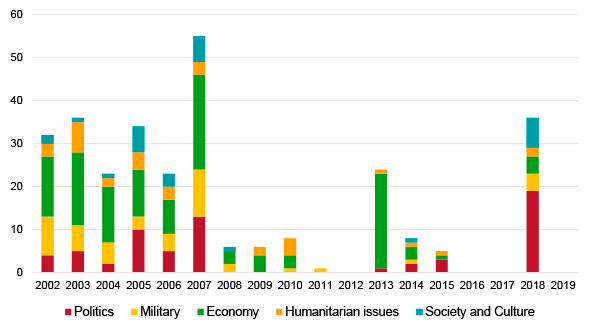

While 36 inter-Korean meetings were organised in 2018, as much as in 2003 at the height of the Sunshine Policy of President Kim Dae-jung, no meetings were organised in 2019 and so far in 2020. Inter-Korean trade is also de facto non-existent, North Korea being more dependent than ever on its trade with China, and the recurring attempt from Seoul to authorize South Korean tourists to go back sightseeing to North Korea never materialized. Even the sugar-for-liquor barter deal presented by the South Korean Ministry of Unification in August 2020 was scrapped after a North Korean company involved in the process was found to have been flagged under international sanctions. This is even more regrettable since Seoul tried several months ago to take advantage of the pandemic to strengthen health cooperation with Pyongyang, which North Korea does not seem at all ready to accept.

Thirdly, Pyongyang and Seoul no longer share the same priorities and interests for each other, Pyongyang’s motives being mostly instrumental regarding Seoul. While South Korea played a central role in the diplomatic process initiated in 2018, facilitating the resumption of dialogue between North Korea and the US and the organisation of the Singapore and Hanoi summits, the country now plays a secondary role. President Moon’s willingness to formalise all the outcomes of previous inter-Korean summits by the National Assembly and to stage the first-ever inter-Korean parliamentary meeting would not change North Korea’s current lack of interest. Indeed, North Korea now needs no intermediary either to communicate with the US or to organise a high-level meeting. Instead, the main problem for Pyongyang is the likely political alternation in Washington, which could bring to power a Democrat Administration far less inclined to make political concessions, let alone concrete ones. On the other hand, since South Korea is not able to bring the economic benefits so long awaited by North Korea, the latter is turning to China, Russia and the countries of South-East Asia. That strategy was set in motion in 2019 but undermined by the COVID-19 pandemic which has made it impossible to inaugurate and open the tourist complex of Wonsan or that of Samjiyon to foreign tourists, or render the long-awaited recent connection of the bridge built by China at Dandong several years ago with the North Korean road network unnecessary.

From summits to renewed threats: no progress on the nuclear and ballistic issue

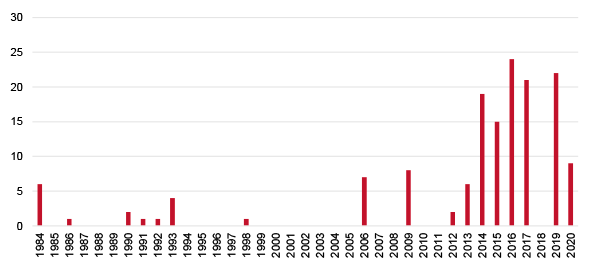

For decades North Korea has remained uncompromising in its objective to develop nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles and other weapons of mass destruction in the face of various international negotiation strategies based on sanctions and incentives, in bilateral or multilateral formats. Despite the very limited hopes following the historic summit in Singapore, it must be acknowledged that there has been no progress on the denuclearisation of North Korea, quite the contrary. Not only have negotiations stalled, North Korea has ended its moratorium on nuclear and long-range ballistic missile tests, and has tested a total of 30 short range missiles and submarine-launched ballistic missile in 2019 and 2020 so far, but Chairman Kim also guided a meeting of the Central Military Commission of the Workers Party of Korea (WPK) last May to and set forth ‘new policies for further increasing the nuclear war deterrence of the country and putting the strategic armed forces on a high alert operation’.4

Indeed, all phases of North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme are currently continuing, including efforts to further miniaturise its nuclear warheads and improve their deliverability, reliability, safety and security. North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile programmes are inseparable, and it should be noted that they have accelerated considerably in recent years. As the tests have multiplied, many new systems have been tested, significantly increasing the potential range and survivability of North Korean ballistic missile capabilities. North Korea is increasing its tactical and strategic ballistic missile capabilities, seeking to protect its territory while developing new capabilities in-theatre. This could potentially lead to a conventional rebalancing and allow greater military flexibility of action, greater accuracy for short- and medium-range targets and greater certainty regarding effects. There could also be better capacities to defeat or degrade the effectiveness of missile defences in the region, as well as a new capacity to manage a potential crisis on the peninsula. This increases the risk of proliferation of missiles and the dissemination of technologies even more given the historical precedents, particularly with regard to Middle Eastern countries. If such capabilities were ever to be present in certain theatres of operations closer to Europe, such as in the Sahel, European states would face unprecedented challenges in terms of force projection and military operations.

The institutionalisation of the possession of nuclear weapons by the North Korean regime and the continuation of its nuclear and ballistic missile programmes in the face of international negotiating strategies mean that the greatest caution is required in the current negotiations. However, current negotiations have stalled after the failures of the Hanoi summit and the Stockholm meeting in 2019. If a top-down approach was and still is essential, partly due to the political nature of North Korea, negotiations at the working level are also crucial to move towards a comprehensive and technical agreement. Yet the depth of recent negotiations seems shallow. In addition, while there has been no concrete progress, even the staging of the destruction of the entrance tunnels to the Punggye-ri nuclear test site being only symbolic, it is very unlikely that there will be any announcement before the US presidential elections in November 2020, as North Korea is no longer even a major issue in US foreign policy compared with 2017 and 2018. It should also be underlined that the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of the country’s borders make any negotiations between North Korea and its partners even more complicated. Not only are North Korean diplomats no longer able to leave the country, including to visit Europe, but many foreign diplomats are leaving the country, as are the British, Germans and even Swedes, who have been playing a key role for several years.

The main risk is precisely that this relative calm in the coming weeks could ultimately result in increased tensions depending on the election results. During the last two political alternations in the US in 2008/2009 and 2016/2017, the pattern has been quite consistent. Upon the arrival of the Obama Administration and the Trump Administration, Pyongyang conducted long-range nuclear and/or ballistic missile tests to put pressure on the new Administration and put itself in a strong position for the upcoming negotiations. In early 2009 North Korea scrapped all military and political deals with the South, launched a long-range rocket in April and carried out its second underground nuclear test in June. In early 2017 North Korea was said to be in the final stages of developing long-range missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads in January, assassinated Kim Jong-un’s half-brother Kim Jong-nam in Malaysia in February, and conducted a successful test of an intercontinental ballistic missile in July. It is therefore highly likely that North Korea will seek to negotiate with the current Administration (if Trump is re-elected) or the next Administration (if Biden is elected) from a position of strength and thus remind the US of the reality of its nuclear and ballistic capabilities. In either case, because of Trump’s lack of interest in a deal or Biden’s willingness to appear less conciliatory than his predecessor, North Korea may seek to return to the international agenda by conducting nuclear, long-range missile or satellite launch tests while securing partial Chinese support in an ever-intensifying Sino-US confrontation.

The eighth congress of the WPK: eight as a lucky or unlucky number?

Last August, the 7th Central Committee of the WPK decided to convene the 8th Congress of the WPK next January, earlier than expected. Chairman Kim notably underlined ‘the deviations and shortcomings in the work for implementing the decisions of the 7th Party Congress’ and so acknowledged that the economic objectives were not reached. If the Congress officially aims to put ‘forward a correct line of struggle and strategic and tactical policies on the basis of the new requirements of our developing revolution and the prevailing situation’, the timing is no coincidence since it could be held few days before or after the inauguration of the US President, planned (if there is no delay in the election results) on 20 January 2021. The objective seems to be clear, to give Kim some elbow room whatever the outcome of the US presidential election by giving him the possibility of adapting to a political alternation, but also to set in motion a new diplomatic sequence, potentially linked to new military or other provocations.

Be that as it may, this tactical flexibility on the part of North Korea in the implementation of its policy, as well as in the definition of the major concepts at the heart of international negotiations, is symptomatic of the regime’s need to adapt to its external environment while defending its interests. The same seems to be true of Chairman Kim’s sister, Kim Yo-jong, who now seems to be playing an important role in relations with the US and South Korea, not so much in the ability to make decisions but rather in her role as a messenger and a sounding board for the policies decided by her brother, while at the same time allowing the latter to blame others should she decide to change these policies. The Congress will be interesting in this respect because it will be associated with a renewal of a part of the elite at the head of the Party allowing to confirm, or to deny, the role played by each other, from Kim Yo-jong to Choe Ryong-hae, from Ri Pyong-chol to Pak Myong-sun, and so on.

Conclusions

Reinvigorating the EU’s strategy: from critical engagement to credible commitments

While all the players on the Korean Peninsula seem to be looking forward and eagerly awaiting the election results in the US, it is essential for Europeans to prepare for all the scenarios for 2021, including the most pessimistic ones. Many observers agree that the strategy of critical engagement the EU’s member states have pursued for the past several years towards North Korea –a combination of both incentives and pressure– has been a partial failure. However, what is needed is not just dialogue or idealistic and impractical policies, but rather agreement on concrete and detailed actions that should be taken to advance common European interests.

We argued in a recent policy paper published by the European Consortium on non-proliferation and disarmament that the EU should pivot from a strategy of critical engagement to implementing a more proactive strategy of credible commitments in four areas: political engagement, non-proliferation, implementation of restrictive measures and engagement with the North Korean people. Such a renewed strategy should be highly coordinated, built on the many initiatives already being taken and facilitated by the appointment of an EU Special Representative on North Korea. Indeed, the EU and its member states rightly affirm on a regular basis that their interests are at stake: the fight against nuclear weapon proliferation and maintaining stability on the Korean peninsula and prosperity in Asia. To defend these interests, such a renewed strategy is essential.

Also, the engagement with the North Korean people is all the more important since the country suffers directly and indirectly from the COVID-19 pandemics . With humanitarian workers leaving Pyongyang and the closure of borders making the arrival of humanitarian aid even more difficult than before, it is the EU and its member states’ moral and political obligation to promote the well-being of the North Korean population. Seoul’s recent proposal to focus on human security as well as health cooperation could be a starting point to further discussion between the Europeans and the South Koreans on how a collective approach to the North Korean issue could be revised. The COVID-19 pandemic, which is already having considerable economic consequences, should not make us forget its strategic but also its humanitarian consequences.

Antoine Bondaz

Director of the FRS-KF Korea Program and Assistant Professor at Sciences Po | @AntoineBondaz

1 Antoine Bondaz (2020), ‘Reinvigorating the EU’s strategy toward North Korea: from critical engagement to credible commitments’, 38 North, 16/IV/2020.

2 ‘KCNA commentary on height of impudence’, KCNA, 17/VI/2020.

3 Antoine Bondaz (2017), ‘Kaesong, caught between two Koreas’, Books and Ideas, June.

4 ‘Supreme leader Kim Jong Un guides enlarged meeting of WPK Central Military Commission’, KCNA, 5/V/2020.

5 Antoine Bondaz (2020), ‘From critical engagement to credible commitments: a renewed EU strategy for the North Korean proliferation crisis’, EU Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Paper nr 67, SIPRI, February.

The Demilitarised Zone between North and South Korea. Photo: Stephen_AU (CC BY-ND 2.0)