Theme[1]

What impact has Russia’s presence and influence in the Southern Neighbourhood had on the resilience of countries in the region and the Atlantic Alliance?

Summary

Russia has a strategy of destabilising Europe’s Southern Neighbourhood.[2] The strategy is opportunistic, practical, instrumental and articulated through the prism of the war in Ukraine. The Kremlin’s strategy is instrumental in four ways: (1) Moscow is fulfilling the objective of provoking the dispersion of Western attention and resources in the context of the war in Ukraine; (2) it supports authoritarian regimes in the Middle East, North Africa and the Sahel through defence agreements; (3) it uses disinformation campaigns based on narratives about how the ‘Global Majority’ (the ‘Global South’) is oppressed by the ‘Collective West’ (the US, the EU and NATO); and (4) the Kremlin’s instrumental strategy is identified with a form of alignment and strategic partnership with other revisionist powers, such as Iran, China and North Korea.

Russia has encountered solid deterrence and containment on the Atlantic Alliance’s eastern front and has intensified its presence in the Southern Neighbourhood in search of opportunities to increase its political and military influence. US non-intervention in Syria (in 2013, over the use of chemical weapons by Bashar al-Assad’s regime) and the US withdrawal from Afghanistan (2021) were perceived by Moscow as a US weakness in the region and a lack of deterrence.

Russia’s presence and influence in the Southern Neighbourhood is part of the ‘Great Game 2.0’. The Great Game of the 19th century pitted Britain against Russia. The 21st century’s Great Game 2.0 includes many more players and takes place mainly in Africa, Latin America and Asia.

Analysis

The Middle East, North Africa and the Sahel: some commonalities

There are many differences between North Africa, the Middle East and the Sahel in terms of the broader geopolitical context and what kind of threat they pose to NATO, but they share some common features, as the regions are undergoing a profound process of transformation of the regional order, shaped by the crisis of central authority and state legitimacy, while the autocratic state model is unsustainable and the path to democracy is tortuous. The consequences of the crisis of legitimacy are numerous: (a) the decomposition of several states (Syria, Libya, Iraq and Yemen); (b) the emergence of ‘sub-states’ whose legitimacy is based on ‘blood loyalties’ (tribes, ethnic/religious groups, clans, etc); (c) the progress of different radical jihadist groups; and (d) the fracturing of Sunni jihadism into two main opposing factions, al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS). The gradual withdrawal of the US, France and the EU from the regions has fostered a power vacuum that is being filled by Russia and China, as well as by Turkey, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Moreover, North Africa and the Sahel have become new theatres of tension and geostrategic competition between the great powers, as has been the case in the Middle East for a long time.

Russia’s global geopolitical goals

Since 2007, when Vladimir Putin at the Munich Security Conference publicly defined the US and NATO as the greatest threats to Russia’s security and defence, Russian politicians have made no secret of the goals of their geopolitical agenda: to create a post-liberal (‘post-Western’ or ‘multipolar’) world order, ie, to undermine US and Western power and leadership; to regain great power status in order to control and protect its economic and natural resources; and, since the war in Ukraine (2014), to upstage the failure of Western attempts to isolate Russia internationally.

Russia’s presence and influence in the Southern Neighbourhood is part of the ‘Great Game 2.0’. The Great Game of the 19th century pitted Britain against Russia. Beyond the immediate battlefield of Afghanistan, the question was: who will dominate Central and South Asia, from the Caspian Sea to the Himalayas and the road to India? It was classic geopolitics. The ‘Great Game 2.0’ of the 21st century involves many more players and takes place in many more territories.

It is a game of rivalry between liberal democracies that seek to protect the international liberal order and revisionist powers that seek to change or destroy it. The structure of the Great Game 2.0 is triangular:[3] it consists of a competition between Westerners and revisionists for power and influence in African, Latin American and Asian countries. These countries, which reject the idea of belonging to a single bloc –whether led by the US or by a growing alignment between China and Russia– are in a position to diversify their partners and allies. The ‘Great Game 2.0’ is who will be more capable of building alliances in Eurasia, Africa and Latin America: the liberal democracies or the revisionist powers?

Russia’s goals, strategies and tools: the Middle East and North Africa

The turning point for Russia’s presence in the Middle East was its military intervention in Syria in 2015. The Kremlin’s intervention was intended to fulfil several objectives at the regional level: increasing its arms sales, preserving internal security in the country while preserving security in its periphery, and becoming a power broker between the West and the region and among the countries of the region. The most important goal was to support and maintain Bashar al-Assad’s regime in power, an objective that Russia has more than fulfilled. The Kremlin justified its intervention in Syria on the grounds that Assad had asked for its help, but above all by the ‘need’ to bring order to the chaos that US interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, and its support for ‘terrorists’ (the opposition to Assad’s regime)[4] had provoked. The war in Ukraine played the role of a catalyst that accelerated some old processes in Russia’s relations with the region, but today (2024) Moscow’s geopolitical goals at the global and regional level are the same as in 2015, with one important addition: Moscow is fulfilling the goal of provoking the dispersion of Western attention and resources in the context of the war on the Eastern front of the Alliance.

Russia does not have a grand strategy for the region in the sense of a coherent long-term plan to order national interests and devise realistic methods to achieve them. But as a deeply opportunistic geopolitical actor, Moscow has a clear vision of its interests in specific situations within the region. This approach to regional politics acts as a practical and instrumentalist strategy, consisting of the ability to improvise and adapt quickly to changing circumstances. The evolving relationship between Russia and Iran is a good example of the Kremlin’s instrumental strategy.

The strategic alliance between Russia and Iran

Russia’s military intervention in the Syrian war in 2015 accelerated military cooperation between Russia and Iran against US targets. Russia was then coordinating its Armed Forces (AF) and the Wagner Group paramilitaries with Hezbollah. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has turned their relationship into a strategic partnership. In the ‘Great Game 2.0’, Iran and Russia, together with China, are part of a united front (though not physically) against the US and the West, as can be seen in the wars in Ukraine and Gaza and in the strategic rivalry between China and the US in the Indo-Pacific over the status of Taiwan. United by a common enemy (the US), the trio is not an alliance and they do not use the same tools to achieve their goals (Iran and Russia use conventional military force, while China’s tools are mainly economic), but they are aligning their foreign policy. All three aspire to create a multipolar world order that is not dominated by the US and thus fulfil their ambition to become the hegemonic powers in their respective regions. All three countries are members of the BRICS. Bilateral trade between them is growing; plans are being drawn up for tariff-free blocs, new payment systems –de-dollarisation– and trade routes that bypass Western-controlled locations.[5] Western sanctions, first on Iran and then Russia, have led these two countries plus China to create an alternative oil market, where payments are denominated in Chinese currency. This oil is often transported by ‘dark fleet’ tankers that operate outside maritime regulations and take steps to conceal their operations.[6]

Moscow, which joined the sanctions regime against Tehran in the 2010s in an effort to curtail its nuclear programme, has begun to protect Iran diplomatically and boost its investment in the country’s economy. In the past two years, Moscow has intensified its ties with the network of Iranian partners and proxies that stretches from Lebanon to Iraq. Since the start of the Gaza war, Russia has stepped up its diplomatic support for Hamas, Hezbollah and Yemen’s Houthis, defending their actions at the UN and blaming the US for their attacks. Moscow tries to handle this diplomatic support delicately, because it aspires to maintain ties with the Persian Gulf Arab countries as well as Israel, so it cannot afford to offer Iranian-linked groups unlimited backing. Russia continues to invest heavily in its ties with Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which have provided significant economic benefits to the Kremlin, but have a hostile relationship with their Iranian proxies.

Although the wars in Ukraine and Gaza are very different from each other, they have three points in common: (1) both Russia and Iran are revisionist powers that aspire to change the international liberal order, and become the hegemonic powers in their regions; (2) the US supports Ukraine and Israel militarily (arms and intelligence); and (3) Iran supports Russia and Hamas, Hezbollah, the Yemeni Houthis and various radical militias fighting Israel and US targets in Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Pakistan and the Red Sea in the same way.

Iran’s supply of Shaheed attack drones for use in Ukraine has received much attention. But what Russia is providing Iran –Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets and helicopters– deserves at least as much attention. Iran remains a major threat to the Gulf states, and supplying Su-35s to Iran would shift the military balance within the region in Iran’s favour. But even if the deal does not materialise, a trend of strategic cooperation has already emerged, including bilateral Russian-Iranian and multilateral Russian-Chinese-Iranian exercises, a pattern that goes back at least five years.

Tools

The Russian presence in the Southern Neighbourhood is part of a combination of synchronous actions: the reactivation of networks established during the Cold War, political and business diplomacy in the nuclear and natural resource sectors and ‘military diplomacy’: defence agreements, the incorporation of the paramilitary Wagner Group (now the ‘African Corps’) into the Russian armed forces and disinformation campaigns.

Sahel

Since 2012, when the Tuaregs rebelled for the fifth time against the government in Bamako (Mali) with the help of al-Qaeda Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and other jihadist groups, the central Sahel region has been the scene of political violence, armed conflicts and civil clashes leading to seven military coups: between 2020 and 2021 in the Sudan, Guinea and Mali (two coups), Chad (2021), Burkina-Faso (two coups in 2022), Niger (2023) and Gabon (2023).

This extreme political instability is the result of a confluence of several factors: poverty, population displacements caused by climate change, tribal rivalries between sedentary, nomadic and semi-nomadic communities, the dominance of organised crime mafias, the weakness and crisis of legitimacy of state institutions, the consolidation of jihadist and other terrorist groups, drug trafficking and endemic corruption.

Regional and international mechanisms, such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), whose mission ends in September 2024, and the two EU missions –EUCAP (EU Capacity Building Mission) and EUTM (EU Training Mission), which end in May 2024 without a consensus among European countries for renewal–, as well as the bilateral actions of France (the counter-terrorist Serval and Barkhane operations) and the US in Niger (an airbase in Agadez) have failed to prevent instability from spreading. Sahelian countries share an anti-French sentiment, but not all are anti-Western.

Following the coups, military juntas in Mali and Burkina Faso have asked France to withdraw its troops, and Niger, in March 2024, has done the same with the US. France’s counter-terrorism approach, which was intended to be comprehensive in stabilising the region, did not prevent, for instance, the collapse in parts of Burkina Faso and Mali of essential services (including health care and education), nor some of the bloodiest inter-ethnic fighting.

The Russian penetration in the region began as a consequence of the French decision to withdraw its forces from CAR in 2017, at a time when armed groups remained active and controlled much of the territory. Russia obtained several military and economic agreements with the CAR government as a ‘stabilising force’, and then perpetuated this model in the Sahel.

The presence of several Islamist terrorist groups in the Sahel –the largest in Mali are al-Qaeda in Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)), the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM); while in Burkina Faso it is Ansaroul Islam (AI) and in Niger ISGS and Boko Haram that are present– is the consequence of two main developments: (1) the civil war in Libya that has been going on since 2011, with the country, as a failed state, exporting weapons and radicals; and (2) of the West’s successful fight against terrorism in the Middle East and North Africa. Defeated in these regions, radicals have moved south to the Sahel.

Jihadism had flourished in the Middle East and North Africa because it has found a favourable cultural and political context (Arab communities, a literate population, a wealth of natural resources and religious fanaticism). In the case of the Sahel, there is no favourable context: there is much poverty and a large illiterate population (who cannot read the Koran). As a result, jihadists identify their radicalisation targets with the various ethnic groups and clans and are thus become directly involved in inter-ethnic conflicts. Their relative success is due to their strategy of ‘owning’ the goals of local ethnicities, presented as partners in a win-win relationship.

The EU, led by France, and the US have not translated their considerable economic investment into an equivalent political and military influence.[7] This is because local actors have embraced their own role in the ‘Great Game 2.0’ by adopting a strategy of diversifying their diplomatic, economic and, above all, military alliances. Local leaders’ perception that Russia has largely succeeded in protecting Bashar al-Assad and his regime in Syria and that it has been successful in fighting the Islamic State in the Middle East has sparked their interest in asking Moscow for the same favour. These developments, along with Moscow’s disinformation campaigns on colonialism and neo-decolonisation, have facilitated Russian penetration in the region. Russia and China are filling the vacuum left by the West thanks to the strategies of local actors to diversify their partners. Russia has gained ground mainly in the military and diplomatic spheres, while China has strengthened its position as a dominant economic power, investing in infrastructure, natural resources and other economic projects.

Russia’s objectives, strategies and tools in the Sahel

The Sahel is not a priority for Russia’s national security, but it is a priority for its foreign policy, because it is part of the ‘Great Game 2.0’. Its main objective is to support its clients, the military juntas of Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad, which have requested its assistance. Diplomatically, Russia’s overall goal is to win more support for its vision of a multipolar world order. At the UN, Moscow lobbies its African allies for favourable votes on issues such as the Ukraine conflict and works to sow distrust in UN peacekeeping missions and other multilateral efforts.

Russia has no political preferences in the Sahel. Its strategy is instrumental and its main aim is ‘to go against the West’. Moscow’s goals and strategies in the region are the same as in the Syrian war: regime protection and the fight against terrorism/political opponents and against US and European interests.

To go against Western interests is Russia’s main strategy, by way of a discrete plan of defence agreements with the countries of the region. This is its modus operandi: first it arranges military deals and arms sales, then it sends technicians to maintain weapons, subsequently it provides ‘military advisors’ and, finally, it attempts to close economic deals. For now, there is no evidence of economic deals in the Sahel, but Russia’s ambition is most likely to profit from Mali’s and Niger’s minerals (respectively lithium and uranium).

Russia’s main tools in the Sahel are military: the Armed Forces, Spetsnaz (Special Forces), the GRU (Military Intelligence Service), the Wagner Group (now known as the ‘African Corps’) and disinformation campaigns. Russia’s economic investment in the region is very low; its presence and influence in the region is neither broad nor deep, but its relative success is due to historical ties dating back to the Soviet era, Russia’s ‘peer’ treatment of local actors (Moscow does not lecture on democracy, human rights or democratic reforms as a condition for its support), but above all because of local leaders’ perception of the Westerners’ failure to solve their problems of poverty, corruption, famine and, above all, inter-ethnic conflicts that overlap with jihadist violence.

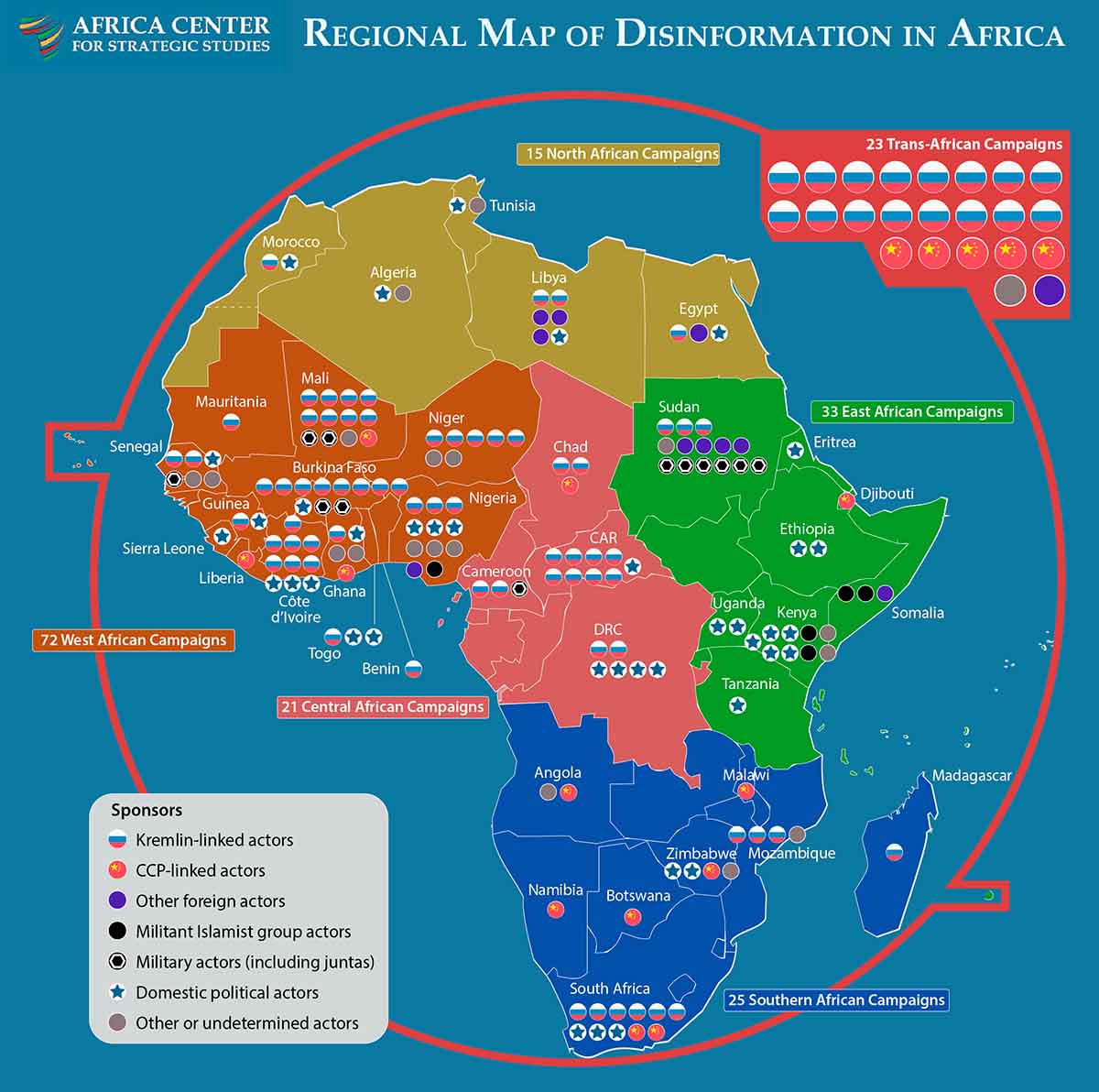

Russia’s impact on the resilience of countries in the Southern Neighbourhood

According to the dictionary of the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language, the word ‘resilience’ connotes ‘the ability of a living being to adapt to a disturbing agent or an adverse state or situation’. The consequence of the ‘adaptation’ of the countries of the Southern Neighbourhood to the disruptive role of both Russia and terrorist groups has been the expulsion of Western countries from the region. Moscow, by providing military and political support to the military juntas and through disinformation campaigns on the role of former colonialist powers and the US in the region, climate change, and the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, is expanding its influence, sowing confusion and anti-Western sentiment. There is a strong link between the extent of disinformation and the instability it has caused. Disinformation campaigns have promoted and validated military coups, intimidated members of civil society into silence and served as smokescreens for corruption and exploitation. Nearly 60% of disinformation campaigns on the continent are sponsored by foreign states, with Russia, China, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia and Qatar being the main sponsors. Russia remains the main provider of disinformation in Africa, sponsoring 80 documented campaigns targeting more than 22 countries. This accounts for almost 40% of all disinformation campaigns in Africa.[8]

Figure 1. Regional map of disinformation in Africa

Russia’s impact on the Atlantic Alliance’s resilience

Russia’s expanding influence in Africa and the Middle East threatens Europe’s stability. Ongoing instability in these regions fuels a steadily growing arms market, which could prove beneficial for Russia in circumventing Western sanctions. Angola, Algeria, Egypt, Syria, Libya and the Sudan are the largest recipients of Russian arms exports on the continent, but the number of African countries buying arms from the Kremlin has been growing over the past two decades. Russia has asserted its influence in three major conflict zones: Syria, Libya and the Sahel. When combined with Russia’s access to Middle Eastern ports, including the Syrian port of Tartus, Russia’s unbridled influence in Libya and its growing presence in the Sahel, including the Sudan, give it a stronger position from which to disrupt NATO’s maritime movements in times of crisis. By securing access to African ports along the Red Sea through the Port of Sudan, and with prospects of securing access to the Libyan port of Tobruk, Russia would be in a position to disrupt naval and maritime passage along the central and eastern Mediterranean and to establish coastal airfields that would enable the global transit of Russian aircraft, including military aircraft. With greater influence in Libya and the Sahel, Russia also gains access to two key migration and human trafficking routes in Africa, which so far there is no evidence it has used. This puts Russia in a stronger position to provoke humanitarian and political crises in Europe in times of hostility.[9]

However, Russia is not the main threat to the Alliance in the Southern Neighbourhood. Its presence and influence is part of the ‘Great Game 2.0’. Russia is a geopolitical threat from which the Alliance’s security problems derive. The main threat in the Middle East is Iran and its ambition to become a hegemonic power in the region, as well as its alignment with other revisionist powers, notably China and Russia. The biggest threat in North Africa is the unlikely but not impossible conflict between Morocco and Algeria. Although the two countries are the most stable in the region, tension between them is growing (they broke off diplomatic relations in 2021, have a conflict over the Western Sahara and have had closed borders since 1994). The main threat in the Sahel is that the whole region could become a huge failed state and/or the base for a new Islamic State.

Conclusions

Some recommendations

There is a clear asymmetry between the scale and character of the threats to NATO’s security in the East and South. The threat on the Eastern front is determined by Russia and is conventional and hybrid. NATO’s Southern Neighbourhood has not left behind its structural vulnerability. Transnational phenomena such as terrorism, organised crime, small arms proliferation and irregular migration flows can be expected to remain among the main factors of instability and insecurity in the South.[10] As Luis Simón has pointed out, NATO’s objectives in the South have not changed substantially in terms of promoting stability in the neighbourhood, considered a fundamental key to Euro-Atlantic security. What has changed is the strategic context and the nature of the threats and challenges emanating from the South. The character of NATO’s strategy for the South therefore needs to be readapted through at least three avenues: (1) a 360-degree deterrence; (2) ‘advanced resilience’; and (3) a transatlantic division of labour for crisis management.[11]

A hypothetical Hamas victory in the Gaza war would be the starting point for a reconfiguration of the regional order, making it all the more important for the US, Israel and Arab allies (mainly Saudi Arabia and Jordan) to maintain a balance of regional power and prevent an Iranian victory. A hypothetical war in North Africa, or the conversion of the Sahel into a major failed state/Islamic State, would increase the impact of the aforementioned instability factors and risks for the Alliance in the Southern Neighbourhood. NATO must be prepared for worst-case scenarios.[12]

Simón suggests that NATO needs to embrace a transition to a more indirect role in stability projection. This reality relates to the emerging concept of ‘forward resilience’, which involves strengthening the capabilities of NATO’s partners to resist pressures from adversaries and address challenges such as terrorism, organised crime and the effects of climate change. The forward resilience strategy must prioritise and give a prominent role to NATO’s partners, including in this new paradigm both regional actors and other relevant entities, and especially the EU. Partners’ local needs transcend the security domain. NATO must move away from its uniform approach to partnerships and adopt a more tailored, flexible and bilateral framework of interactions with countries in the region.[13]

The keys to a future Western presence in the Sahel region should focus on four points:

- Unity of action: any comprehensive and consensual approach to the new Sahelian reality must harmonise the interests of the countries on NATO’s southern borders and at the multilateral and European Atlantic (NATO) levels. This action could start with bilateral contacts by countries that have a good image in the region (Germany and Spain in particular) as EU and UN missions come to an end this year. The main objectives of renewing the European presence in the region should be to support local democratic forces, to improve intelligence sharing, and to have a pragmatic approach to the region by finding a balance between the demands of democratic values and the local realities of poverty and conflict, which are often more urgent to resolve. This means creating a mechanism to control investments that disappear due to corruption. In the case of the Middle East, minilateralism (ad hoc local alliances) could work as demonstrated by the united response of the US, France, the UK, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Israel to Iran’s attack.

- Reconciliation and dialogue: with a view to restoring political and security stability, the West should promote national processes of dialogue and reconciliation between communities and ethnic groups/clans.

- Endogenous development: there is a need to promote endogenous capacities for economic development, with financial and investment support mechanisms tailored to local needs.

- Fight for hearts and minds: before any successful strategy to fight Islamist terrorism and organised crime mafias, as well as the malign influence of Russia and other actors, it is necessary to win the support of the local population.

It is important to find ways to maintain the Western presence in the region, because it will be very difficult to return if expelled from the region, but above all because it is the key to the resilience of regional countries and NATO, as well as to the Alliance’s 360º deterrence.

[1] This paper is based on a broader analysis presented by the author to the Resilience Committee at the HQ NATO (unclassified meeting) on 19/IV/2024.

[2] On the concept of the Southern Neighbourhood see Luis Simón & Vivien Pertusot (2017), ‘Making sense of Europe’s Southern Neighbourhood: the main geopolitical and security parameters’, Elcano Royal Institute, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/making-sense-of-europes-southern-neighbourhood-main-geopolitical-and-security-parameters/.

[3] Robin Niblett describes the competition between the US and China for the Global South as triangular in his book The New Cold War. How the contest between the US and China will shape our century, Atlantic Books, London, 2024.

[4] More details on Russia’s role in Siria in:Mira Milosevich-Juaristi (2017), ‘La finalidad estratégica de Rusia en Siria y las perspectivas de cumplimiento del acuerdo de Astaná’, Elcano Royal Institute, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/analisis/la-finalidad-estrategica-de-rusia-en-siria-y-las-perspectivas-de-cumplimiento-del-acuerdo-de-astana/.

[5] ‘How China, Russia and Iran are forging closer ties’, The Economist, 18/III/2024, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/03/18/how-china-russia-and-iran-are-forging-closer-ties.

[6] ‘The axis of evasion: behind China’s oil trade with Iran and Russia’, The Atlantic Council, 28/III/2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-axis-of-evasion-behind-chinas-oil-trade-with-iran-and-russia/.

[7] Mira Milosevich-Juaristi (2023), ‘Rusia en África y las posibles repercusiones para España’, Policy Paper, Real Instituto Elcano, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/policy-paper/rusia-en-africa-y-las-posibles-repercusiones-para-espana/

[8] Africa Center for Strategic Studies (2024), ‘Mapping a surge of disinformation in Africa’, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mapping-a-surge-of-disinformation-in-africa/.

[9] Daniel Kim (2024), ‘Arms race alert: world military spending hits record $2.4 trillion’, https://viewusglobal.com/world/article/61178/.

[10] Luis Simón & Piere Morcos (2022), ‘La OTAN y el Sur tras Ucrania’, Real Instituto Elcano, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/analisis/la-otan-y-el-sur-tras-ucrania/.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.