Theme: After initial failure in June, the European Council has managed to close the EU budget for 2007-13.

Summary: The agreement on the EU budget for 2007-13, reached by the European Council on Saturday, December 17, may be assessed from two standpoints: its necessity and its value. Coming on the heels of the fiasco of the constitutional referendums in France and Holland in May and June, and the European Council’s failure in June to reach a budgetary agreement, the December agreement was essential. The mere existence of an agreement is the best possible news for the Union. However, our contentment should not blind us to the fact that this is an especially ungenerous agreement in terms of the needs of the Union and, above all, the needs of its new members. Therefore, although the agreement may close one of the EU’s many open fronts and thus help break the deadlock in the process of ratifying the European Constitution, these negotiations clearly show that the method used up to now to negotiate the budgets no longer works in the interests of the Union as a whole. This paper concludes that we must use the available time ahead of us to lay the groundwork for a new budget-making process that properly represents the interests of the European Union as a whole when the European Council conducts its negotiations behind closed doors.

Analysis

Agreement the Second Time Around

The agreement reached in the European Council in the wee hours of last

Saturday puts an end to negotiations among member states on the Union’s long-term budget (the financial perspective 2007-13). The agreement will (presumably) now be ratified by the European Parliament, which can only approve or reject it, but cannot make any amendments. The negotiations were carried out in the expected atmosphere: prior threats of vetoes, semi-bellicose language, total uncertainty until the last moment, a profusion of bilateral negotiations in hallways and offices, and finally, a last-minute, late-night agreement. As could be expected, unanimous satisfaction expressed by the leaders has been followed by the inevitable flood of criticism at home and familiar arguments about the real magnitude of the concessions and the resulting sacrifices.

The early morning hours of December 17 will rightly go down in EU history –a history in which budget negotiations have played a major role–. What we see is that the conditions for a budget agreement remain the same as in Berlin in 1999 and Edinburgh in 1992: everyone wins something, everyone loses something and, in accordance with the etiquette of negotiations, only the most inexperienced claim total victory in public. The result of the dynamics of the negotiations –which had an entirely national tone– is that there was more discussion of what is at stake for member states than what is at stake for the European Union as a whole. It is therefore useful to consider the agreement in European terms before going on to assess it in national terms, which will be done specifically in a separate analysis: The European Union’s Financial Perspective for 2007-13: A Good Agreement for Spain (II).

Ye Shall Know them by their Budgets

The EU took in ten new members in May 2004, which made it necessary to find additional funds in the 2004-06 budgets to finance the enlargement. However, the financial perspective for 2007-13 is the first one designed by the 25-member Union. For sceptics who disbelieve political rhetoric and maintain that the only true measure of the intentions and goals of a political body are its budgets, the enlarged 25-member EU, in which we will live until 2017, has set its spending at 862 billion euros.

As usual, two main items on the European budget are direct subsidies to farmers, which will take approximately 34.5% of the budget (293 billion euros), and spending on structural and cohesion policies, which will absorb another 35.2% (299 billion euros). The rest of the budget will be used to support the rural and fishing sectors (77.7 billion euros); foment growth, employment and innovation, in accordance with the Lisbon Agenda (72 billion euros); maintain the EU’s presence in the world (50.3 billion euros); and finance citizenship, freedom, security and justice policies (10.3 billion euros). Meanwhile, the much reviled bureaucracy in Brussels will consume 50.3 billion euros over seven years (only 5.8% of the budget).

This is, therefore, a budget that continues the trend that began in 1992 with agricultural policy reform and which became firmly entrenched in 2002 with the decision to undertake annual reductions in agricultural spending through nominal stabilization (see Elcano Royal Institute, ARI nr 88/2002, Las claves de un acuerdo sorpresa, at ARI 88-2002). It is a way of progressively reducing price-related interventions in the agricultural market and strengthening the social component of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) by increasing direct subsidies to farmers (not linked to production) and by increasing rural development funds.

This is clearly a move towards an agricultural model that is more compatible with EU development policy, more in accord with EU commitments within the World Trade Organization (WTO) framework and with the Union’s own environmental policy, and less onerous for European consumers. Many feel that headway is being made too slowly. However, in contrast to frequent criticism that the European budget allocates too much money to agriculture (and too little, for example, to innovation), it must be kept in mind that since this is a continent-wide policy, European agricultural spending accounts for all agricultural spending in the EU. In other words, member states are free to spend as much money as they want on research and development through their national budgets, but not on agriculture, where there is no possibility of national co-financing.

At the same time, the new budget reflects the growing importance of structural and cohesion policies, especially since the latest EU enlargement, as well as the Union’s new priorities in: research, development and innovation (R&D and innovation); foreign policy and security and freedom; security and justice. However, if any criticism can be made of the coherency of the British presidency, it must surely focus on the deep cuts in EU funding to improve European competitiveness (Lisbon Agenda): of the 121 billion euros requested by the European Commission, only 72 billion was finally approved at the request of the presidency (proving that member states continue to prefer the national framework for R&D and innovation investment). These very significant cuts stand in sharp contrast to Primer Minister Blair’s rhetoric, both in his speech to the European Parliament in June and at the October Hampton Court summit, which was entirely devoted to improving the competitiveness of the European economy in the context of economic globalisation. Likewise, the presidency’s planned cuts in EU foreign policy spending are questionable, since the Union’s development and neighbourhood policies are certain to require additional resources until 2013.

The Size of Europe

From the European perspective, the size of the budget is what matters most. The enlargement in 2004 brought in ten new members, all with extraordinary financing needs in terms of structural and cohesion policy. Enlargement to Romania and Bulgaria will also soon be upon us, so that in less than five years the European Union will have increased its population by more than one hundred million people –the immense majority of whom (practically 90% of the citizens of the new member states) will be living in regions with income levels not only far below the community average, but also below the threshold of 75% of this average which qualifies a region to receive structural funds–.

In the enlarged Union, the income gap will widen dramatically: while the ten richest regions in the EU will have an average income equivalent to 189% of the community average (EU-25 = 100), the income of the ten poorest regions will stand at 36%. The Union will have added millions of new farmers and thousands of new kilometres of external borders, while nearly doubling the number of member states. However, this huge task is being undertaken with the same financial resources as those available to the EU in 1985, before Spain and Portugal joined.

Table 1. A Dwindling Budget

| € mn | European Commission January 2004 | European Parliament June 2004 | Luxembourgian Presidency June 2005 | British Presidency December 2005 | Final Agreement December 17 2005 |

| Sustainable growth | 457,995 | 446,930 | 381,604 | 368,910 | 380,129 |

| Competitiveness | 121,687 | 110,600 | 72,010 | 72,010 | 72,010 |

| Cohesion | 336,308 | 336,330 | 309,594 | 296,900 | 308,119 |

| Management of natural resources | 400,294 | 392,306 | 377,800 | 367,464 | 370,854 |

| Direct subsidies | 301,074 | 293,105 | 295,105 | 293,105 | 293,105 |

| Citizenship | 14,724 | 16,053 | 11,000 | 10,270 | 10,270 |

| Security, justice | 9,210 | 9,321 | 6,630 | 6,630 | 6,630 |

| Citizenship | 5,514 | 6,732 | 4,370 | 3,640 | 3,640 |

| Europe in the world | 62,770 | 63,983 | 50,010 | 50,010 | 50,010 |

| Administration | 57,670 | 54,765 | 50,300 | 49,300 | 50,300 |

| Equalization | 800 | 800 | 800 | 800 | 800 |

| Total | 994,253 | 974,837 | 871,514 | 846,754 | 862,363 |

| Commitment ceiling (% GNI) | 1.24 | 1.18 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.045 |

Source: European Commission and British presidency. Data on appropriations for commitments (€ million).

Despite having available up to 1.27% of community GNI, the 2005 budget, recently approved by the European Parliament, sets the Union’s projected spending at 1.01% of GNI (in appropriations for payments). In practice, since a part of the budget is not spent in the end, due to difficulties with planning and implementation, real budget expenditures for 2006 will likely be below 1% (as was already the case in 2004, when it ended up at 0.98%). By comparison, in 1985, immediately before Spain and Portugal joined, EU spending stood at 0.92%.

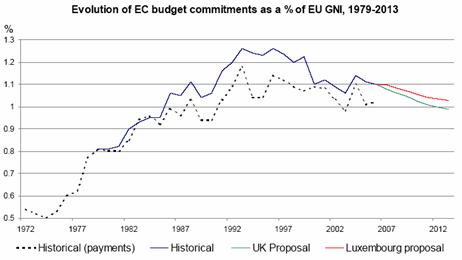

For 2007-13, this situation is now consolidated, since the commitment ceiling is 862 billion euros (1.045%), while the Commission had proposed a ceiling of 994 billion (1.24%). In short, 131 billion euros have been saved. This is highly paradoxical: the 25-member EU plans to maintain a spending ceiling similar to the one established for the 10-member Union. European leaders are obviously satisfied with this, as the chart distributed by the British presidency on December 5 proves (Graph shown below). The British proposal is indeed characterised by its austerity.

Graph 1. More Europe with Less Money

The Reason for the Cuts

There are two reasons for this budgetary minimalism: one reasonably acceptable, the other unjustifiable. The first one has to do with the poor economic situation in some of the countries that contribute most to the budget, especially France and Germany. With economies on the verge of recession for several years, and under constant pressure from the Commission to keep the budget deficit below 3% (in order to abide by the Stability and Growth Pact), it is perfectly understandable that many countries want to reduce their contributions to the European budget as a way of reducing national budgetary imbalances. However, the need for financial discipline, though understandable, has led to a focus on the European budget that is overly focused on contributions, even at the cost of sacrificing budgetary rebates which, under other conditions, would not be so lightly overlooked. This has revealed a triumph of the logic used by the typical finance minister: European budgets mean only expenditures, but never direct income (since the beneficiaries are farmers, workers, universities and others in each country). This makes finance ministers reluctant to consider any new contributions, regardless of the benefits to their own countries.

The second source of cuts has to do with the widespread idea of ‘net balance’, which is entirely unjustifiable in terms both of fairness and practicality. The net balance focus means measuring the costs and benefits of EU membership for each member state, in terms of the size and sign (positive or negative) of its budgetary balance with the Union –as if all the costs and benefits of EU membership could be expressed in a budget–. It also means ignoring European citizens, who ultimately finance the European budget through their taxes, and who should reap its benefits.

This focus on net balances –which has spread like wildfire since Britain managed in 1984 to receive a rebate for two thirds of its contribution to the EU budget– has been extremely harmful to the Union as a whole, since it has undermined the legitimacy of European spending in the eyes of citizens in the most prosperous countries by appearing to validate the incredible assertion that EU membership is costly. Hiding the fact that contributions to the EU budget are strictly equitable (since payment is made based on the size of the economy), the so-called ‘net contributors’ (Germany, Britain, France, Holland, Austria and Sweden) have been cooperating since December 2003 to reduce the EU’s total spending and even generalize the British rebate mechanism to the rest of the member states (see the ‘Letter of the Six’, December 15, 2003, proposing a 1% spending ceiling, and the irritated response from the president of the Commission, Romano Prodi, Commission IP/03/1731).

How the Deadlock was Broken

In line with this philosophy, Germany (which makes very large contributions to the EU budget) has not sought an agreement on how to allocate funds for 2007-13, but rather has set out first of all to impose a low spending ceiling for the entire period, with the idea of later becoming more flexible. However, the December 16-17 negotiations showed that a spending ceiling as low as the one proposed by the British presidency (1.03%) causes such great conflict over distribution that no agreement is possible.

The eleventh-hour proposal by German Chancellor Angela Merkel to raise the spending ceiling to 1.045% was one of the keys to breaking the deadlock in the negotiations. The new ceiling put an additional 13.06 billion euros on the table to reach agreements and consensus (on December 14, the British presidency had raised the previous December 5 ceiling to 849 billion euros). Since contributions in the EU are proportional to the size of each country’s economy, Germany will have to add approximately one fifth of that amount to its own contribution. Merkel’s proposal is therefore a courageous one and reflects both great leadership and great self-confidence on the domestic front, since criticism was to be expected. It also shows that there is considerable truth to the idea that ‘Europe is when everyone agrees and Germany pays’.

Britain provided the other important key to breaking the deadlock in the financial perspective. It was Tony Blair who finally gave in and accepted that his country would chip in its full part to finance the costs of enlargement. Blair has given up his demand for a radical overhaul of the CAP and has settled for exempting Britain from the Union’s agricultural spending in new member countries. However, Britain will naturally have to contribute its share to the EU’s enormous spending on cohesion in these countries over the next several years. This is earning him great criticism in Britain, which shows –as in Merkel’s case– that leadership does not consist of imposing sacrifices on others, but in taking them on oneself. In this case, Britain will have to contribute an amount similar to that promised on Germany’s behalf –approximately an additional 2.5 billion euros–. In the end, the British rebate will continue to exist, but it will not automatically grow in proportion to EU spending. Therefore, although Britain will continue to receive a rebate of two thirds of its net contribution to the community budget, this will not include the spending on cohesion that the Union will carry out in the new member countries.

Along with Merkel and Blair, Chirac also deserves some critic. He has kept a low profile, avoiding open confrontation with Blair, but has categorically rejected various British proposals that would involve a commitment to make new reductions in agricultural spending during the period of the current financial perspectives. As always, France finds itself in an enviable situation in terms of European construction: nothing is possible without or against France and, as a result, EU agricultural policy –which benefits France above all, but Spain as well– remains stable.

Conclusion: Europe is the only negotiating forum where a bad agreement is always preferable to no agreement. This is because the Union is itself an ongoing negotiating system in which all issues are interrelated. In negotiating terms, a ‘shadow of the future’ effect relativises the value of present agreements and disagreements in light of foreseeable future agreements and disagreements.

All in all, the main problem facing Europe is not the difficulty in reaching agreements. As has been demonstrated, agreement is possible because there are always areas in which concessions made by one party may intersect with those made by others. Agreement has therefore been possible because Germany has agreed to pay a little more and Britain a little less, and France has not ruled out a further adjustment of the agricultural policy in the future.

As a result, the real problem is not to accommodate national interests, but to accommodate European interests. It is easy to imagine what would happen in Spain if the national budgets were prepared by the regions (known as ‘Autonomous Communities’) in the framework of mandatory unanimous agreement by the Conference of the regional premiers. Negotiations would focus on the fiscal balances of each autonomous community, not on the real needs of citizens or collective interests. The national budget would reflect the relative power and negotiating skill of each autonomous community, at the cost of the coherency of budget design and the integrity of the goals pursued.

Something similar occurs now in the European Union: the Commission and the Parliament can propose whatever they consider to be the ideal spending level for the Union, but it is the member states who make the final decision. This makes for a vicious circle, since the Commission and Parliament do not directly collect the contributions they receive, nor are they truly responsible to citizens for the policies they propose. At the same time, since member states are responsible to public opinion at home, they bring unbalanced positions to the negotiating table, to the detriment of the interests of the Union as a whole.

In 1765, the American colonies resisted a law that taxed printed paper (the Stamp Act) with the argument that they lacked the capacity to elect and therefore to control the representatives who decided the taxes that American citizens had to pay. Since then, ‘no taxation without representation’ has become a basic concept of democracy. The European Union has a similar problem: as long as the EU does not collect its own taxes, responsibility for managing them will remain mainly at the national level, which will inevitably subject European budgets to a national bias.

José Ignacio Torreblanca

Senior Analyst, Europe, Elcano Royal Institute