Theme

The EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement will have significant effects on the bilateral relation and the international liberal economic order.

Summary

The new Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) between the EU and Japan is the biggest free-trade agreement that the two parties have ever signed. Due to its size it has implications for the rest of the world and for the world trade order. This analysis assesses the prospective magnitude of the EPA and whether it will contribute to revitalise the international liberal economic order.

Analysis

Before analysing the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) it is useful to recall how it came about. In 2013 the governments of the EU member states instructed the EU Commission to start negotiating a free trade agreement (FTA) with Japan. At that time, the negotiations were considered as secondary by both parties to talks with the US: Europe was trying to forge the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and Japan was in the process of finalising the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) with, besides the US, 10 other nations. For both Europe and Japan at least part of the rationale for negotiating an FTA between them was to avoid the TTIP and TPP putting Japanese firms in Europe and European firms in Japan at a competitive disadvantage.

The negotiations were therefore fuelled by the so-called juggernaut theory (Baldwin & Robert-Nicoud, 2015): the negotiation of one FTA increases the incentive for other countries to also negotiate FTAs in order to avoid being crowded out. The result is a network of FTAs that links all relevant trading nations; indeed, under certain conditions (eg, in the absence of restrictive rules of origin) such a network would be as good as universal free trade. So, in 2013 it seemed as if, soon enough, the former Triad powers –the US, Japan and Europe– would be connected through a complete network of FTAs. Some even talked about a novel multilateral order that could emerge from the combination of these three agreements.

In late 2016 the election of Donald Trump as US President halted the process, at least temporarily. This drove the EU and Japan towards a faster completion of their own negotiations. The EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EU-Japan EPA) was formally signed on 17 July 2018 and the ratification process started, with the accord coming into force on 1 January 2019.

How significant is the EU-Japan EPA?

In international trade politics, size matters. When two large economies enact a trade agreement they affect other trading nations through the implied changes in the structure of international trade and through the application of new rules, which may well inspire others to follow.

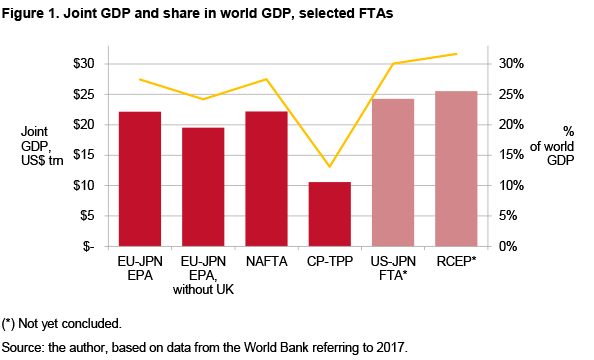

How big is the FTA? One way to measure it is to look at the joint GDP of the signatories. The relevance for the world trade system is best studied using current US$ (or any other currency) instead of measures using purchasing power parities. Through this lens, the FTA certainly is very large: as of 2017 it covers a joint gross domestic product (GDP) of more than US$22 trillion, or 27.5% of the world total (see Figure 1). The EPA is only marginally smaller than the joint GDP of NAFTA, the North American FTA that will, once parliaments have ratified the revised agreement, change its name to USMCA, the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement. The latter is around twice as large as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CP-TPP) that brings together 11 countries including Australia, Canada, Japan and Mexico. The EU-Japan EPA is somewhat smaller than the projected US-Japan agreement, which would account for around 30% of the world’s GDP, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement, which seems almost concluded and would bring the 10 ASEAN (Association of South-East Asian Nations) together with six regional powers, including Australia, China, India, Japan and South Korea. Should the UK leave the EU, the GDP covered by the EU-Japan EPA would drop to US$19.5 trillion. In sum, the EU-Japan EPA is large, but it has important competitors in the global race, some of which have the potential to profoundly influence global trade governance discussions.

In terms of trade volume covered, the EU-Japan EPA is relatively small. Figure 2 shows that in 2017 EU goods exports to Japan amounted to US$67 billion, or 0.5% of the world total; the opposite direction saw a trade flow worth US$77 billion, or 0.6% of world exports. Services exports amounted to US$34 billion and US$30 billion, respectively. In total, the EU-Japan EPA covers trade worth approximately US$209 billion, or 1.2% of world trade, not accounting for intra-EU trade flows.Figure 2. Trade in the Triad

| Exporter | Importer | Goods | Services | All trade | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US$ bn | % of world | US$ bn | % of world | US$ bn | % of world | ||

| EU | World | 2,123 | 15.2 | 935 | 24.6 | 3,057 | 17.3 |

| EU | Japan | 67 | 0.5 | 34 | 0.9 | 102 | 0.6 |

| EU | US | 419 | 3.0 | 241 | 6.4 | 660 | 3.7 |

| Japan | World | 698 | 5.0 | 174 | 4.6 | 872 | 4.9 |

| Japan | EU | 77 | 0.6 | 30 | 0.8 | 107 | 0.6 |

| Japan | US | 135 | 1.0 | 44 | 1.2 | 179 | 1.0 |

| US | World | 1,546 | 11.1 | 752 | 19.8 | 2,299 | 13.0 |

| US | EU | 283 | 2.0 | 231 | 6.1 | 514 | 2.9 |

| US | Japan | 68 | 0.5 | 44 | 1.2 | 112 | 0.6 |

| World | World | 13,929 | 3,792 | 17,721 |

Note: services trade is ‘total services’; goods trade pertains to 2017; services trade to 2016; and intra-EU trade is excluded.

Source: WTO.

To the extent that the EU-Japan EPA has implications not just for the bilateral but also for the overall trade of its signatories –for instance, because it implies changes to governance structures which apply multilaterally– it has systemic relevance. If it only concerns bilateral market access, its systemic relevance is likely to be minor, since, as we have seen, relative to world trade, EU-Japan trade flows are small. Some elements of the agreement have implications for EU and Japanese exports to the entire world. Looking at total EU and Japanese exports to the entire world, the EPA appears to be quite relevant systemically: the EU accounts for around 15% of world goods exports and 25% of world services exports, while Japan accounts for around 5% in both goods and services exports.

Moreover, both regions are important sources of foreign direct investment (FDI). According to the EU Commission in 2016 the Japanese FDI stock in the EU was worth around €206 billion. The EU’s FDI stock in Japan stood at €83 billion. Thus, the EU accounted for around 34% of total Japanese outward FDI while European investment in Japan, at 1.1% of the total, is relatively negligible as a share of total European outward FDI.

The numbers suggest that the EU and Japan follow different modes of servicing foreign markets. European firms serve the Japanese markets primarily via exports while Japanese firms have strong production capacities in Europe.

How innovative is the EU-Japan EPA

Clearly, how influential the FTA is for the world trade order depends not only on the combined size of the partners but also on the ambition in the text. Moreover, the extent to which the agreement matters systemically depends on whether its provisions are bilateral in nature (ie, bind each party only with regard to the other) or multilateral (ie, affect the way business is conducted relative to all trade partners).

There is no doubt that the agreement is among the most modern and most comprehensive to have recently entered into force. Its text has 23 chapters and a long list of annexes. Felbermayr et al. (2019) argues that the EU-Japan EPA shares textual, contextual and substantive similarities with the EU-Korea FTA, which entered into force in 2011; this view is also that of Chowdhry et al. (2018) and Dreyer (2018). While this means that the agreement is relatively standard in many of its provisions, it also offers the opportunity to predict its possible effects because the EU-Korea agreement has been studied extensively.

However, the EPA goes beyond classic areas of market access. The careful analysis of Chowdhry et al. (2018) concludes that the agreement ‘establishes an ambitious framework to further liberalize and better organize trade, covering goods, services, intellectual property and investment, tariff- and non-tariff measures, and regulatory cooperation’. Indeed, due to the sheer size of the partners, and given its depth and breadth, one can expect the agreement to project its size onto the world trading system. This is particularly true in the areas of corporate governance, SMEs and climate change, where the parties have broken new ground by implementing new provisions. The latter apply multilaterally, ie, not exclusively on the bilateral relationship but to all trade partners. Therefore, it is correct when Chowdhry et al. conclude that the ‘EPA is set to become a benchmark for future trade agreements’.

However, there is, as always, room for further improvement. In particular, this is true in the areas of investment protection and data flows. Undeniably, the agreement was concluded under substantial political pressure due to the US termination of the TPP process and the stalemate reached between the EU and the US over the TTIP.

The agreement contains provisions to promote and facilitate bilateral investment, eg, commitments on national and MFN treatment. It also forbids an extensive list of performance requirements as conditions for establishing or operating enterprises in the goods and service sectors. However, the agreement does not include the new Investment Court System (ICS) that the EU uses to replace the traditional Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) tribunals. Had Japan accepted the new European model, the ICS would have registered an important boost that would have resonated in many parts of the world. However, talks about investment protection continue.

Many services are very data intensive. This is true for financial services, telecommunications and logistics, where trade flows between the EU and Japan are very substantial. In July 2018 the EU and Japan concluded talks to recognise each other’s personal data protection regimes as equivalent. This mutual adequacy decision is important in ensuring that the EU’s new data protection rules under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) do not disrupt the Union’s services trade with Japan. The mutual recognition agreement (MRA) was deliberately separated from the trade agreement; nonetheless, its existence is crucial as services trade and data flows are strongly complementary; without the MRA, the EU-Japan EPA would be void in many service industries.

Yet the EPA text contains no language guaranteeing the free flow of data, allegedly because the EU’s members were unable to agree on a common position. This potentially puts EU businesses at a disadvantage as the recently concluded CP-TPP agreement between Japan, Canada and many other members of the Asia-Pacific contains such provisions. Moreover, the adequacy decisions are unilateral and can be revoked at very short notice: there is no real legal certainty.

Effects on insiders and outsiders

Free-trade agreements such as the EU-Japan EPA are often criticised because they may give rise to potential trade diversion effects that harm trade partners. This is a serious argument that goes back to Jacob Viner’s book The Customs Union Issue of 1952. However, as discussed in the introduction, it is exactly the threat of trade diversion that gives rise to a juggernaut effect: other countries face incentives to conclude FTAs; the denser the global network of bilateral trade agreements, the closer the world is to multilateral free trade.

In order to assess the effect of the EU-Japan EPA on third countries, one has to turn to quantitative impact assessments. A number of studies have provided insights. The EU’s Directorate General for Trade published a quantitative study in 2010 conducted by Sunesen et al. (2010) that assessed the impact of bilateral barriers to trade and investment between the EU and Japan. The assumed trade cost shocks were mainly informed by expert judgments, while the more recent study by Felbermayr et al. (2019) employs a more rigorously data-driven approach. Benz & Yalcin (2015) stress the importance of intra-industry trade and labour market frictions, but they have little to say on third-country effects. The European Commission (2016) presented yet another study, which relies strongly on dynamic gains from trade, where substantial uncertainties pertaining to model choice and calibration exist, so that the effects are likely to define upper bounds. There is also a quantification conducted by the Cabinet Office of Japan (2017). Its CGE model considers TFP increases by trade liberalisation, labour supply in response to real wage and capital accumulation by investment. Again, given the reliance on dynamic gains from trade, the results may identify upper bounds. Finally, Kawasaki (2017) uses the GTAP model to measure the impact under the assumption that tariff rates go to zero immediately and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) are reduced by 50%.

The following discussion draws on the results of Felbermayr et al. (2019), whose qualitative predictions are comparable to other studies. The advantage of Felbermayr et al. (2019) is that the work has been through the peer-review process of an international academic journal. The study finds that the largest gains for Europe are to be found in the agri-food sector, while in Japan various manufacturing sectors are bound to benefit the most, followed by services. In absolute terms Japan and the EU reap very similar welfare gains, but relative to the baseline Japan’s gains are three times as large as Europe’s. The study also finds that the structure of Japanese regional value chains changes as firms source more from Eastern Europe but less from ASEAN countries. This, in turn, implies that some ASEAN countries could lose out as a consequence of the agreement.Figure 3. Real income changes by regions (%)

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.31 | Europe, n.e.c. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| UK | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.11 | India | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| RoEU | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | Middle East | -0.00 | -0.00 | -0.00 |

| Germany | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | Africa | -0.00 | -0.00 | -0.00 |

| France | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | Latin America | -0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Italy | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | ASEAN, n.e.c. | -0.00 | -0.00 | -0.01 |

| Vietnam | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | Malaysia | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.01 |

| Rest of World | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | China | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.01 |

| Oceania | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Singapore | -0.01 | -0.00 | -0.01 |

| Philippines | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | South Korea | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.01 |

| US & Canada | 0.00 | 0.01 | -0.00 | Thailand | -0.02 | -0.02 | -0.02 |

| Indonesia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Taiwan | -0.03 | -0.02 | -0.03 |

| World | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

Note: S1 simulates the EU-JPN EPA taking the global trade governance system as given by 1 January 2018; S2 simulates the EU-JPN EPA under the assumption that the UK separates from the EU under a hard Brexit; and S3 simulates the EU-JPN EPA based on a world with a ratified CP-TPP.

Source: Felbermayr et al. (2019).

Figure 3 shows how the real income (ie, real GDP per capita) of various countries and regions is affected by the EU-Japan EPA. It shows three scenarios: S1 reflects the state of the world as of 1 January 2018; S2 modifies the baseline by assuming that a hard Brexit has occurred and that the UK is no longer part of the EU; and S3 does not assume a Brexit but allows for the CP-TPP deal to be fully implemented. There are a number of important insights. First, the EU-Japan EPA increases real income in Japan and in the EU, regardless of the scenario. Secondly, the quantitative effects are relatively small. Real per capita income is expected to rise by around 0.3% in the long-run. This is a permanent income gain, but it is clear that other trade agreements such as the TTIP for the EU or the full TPP (ie, including the US) would have boosted income by more. Third, the agreement does hurt outsiders, in particular in Asia, but the effects are small and, most likely, not statistically distinguishable from zero.

The conclusion, therefore, is that the EU-Japan EPA does not hurt outsiders in any substantial way, but it does benefit the insiders. From that perspective, it rather incentivises further free trade agreements, such as a deepening of Asian integration through RCEP and the conclusion of FTAs between ASEAN countries and the EU. In sum, it revitalises the liberal world trading system rather than undermining it.

Beyond the EU-Japan EPA

However, despite the positive symbolism of the new agreement and its very real economic benefits, one might question how eager the parties to the EPA really are to uphold the liberal international order. With regard to the EU, one cannot but notice the difference between the official communication and actual trade policy actions. Only recently a number of initiatives have made it harder for Asian exporters, including Japan, to serve the EU market. One particularly blatant example is the new safeguard tariffs on steel and aluminium imports, matching the infamous tariffs that US President Trump has imposed by claiming national security concerns and relying on US ‘Section 232’ –albeit for imports above recent historical levels–. The EU applies its duties on all trade partners, without exception, even if it has free-trade agreements in place as with Korea and Japan.

Secondly, Brussels’ new directive for renewable energy (RED II) risks holding up trade talks with ASEAN, a fast-growing region and an important backyard for the Japanese economy. The threat of indiscriminate banning of sustainable biofuels from palm oil produced in ASEAN countries will almost certainly trigger legal actions against the EU before the WTO.

Third, a technical piece of regulation called the Goods Package is quite likely to increase the cost of exports to the EU from all over the world and to provoke new trade disputes. The drafting of the new legislation has the laudable intention of protecting EU consumers against ‘unsafe’ products, but by assuming that all locally produced goods are safe and all imports are unsafe, it is directly discriminatory. The point is that the Goods Package, if it becomes law, will subject almost every parcel to meaningless inspections even with compliant importers. This will be particularly painful for small-scale exporters, which the EU-Japan EPA tries to activate.

These issues and many more –such as the recent imposition on shaky grounds of anti-dumping duties on rice or on e-bikes by the EU– dilute the message of the EU-Japan EPA. Indeed, since 2013 EU imports have grown from €2193 billion to €2494 billion (a 14% rise), while tariff income as recorded by the EU Commission has grown from €20.2 billion to €25.4 billion (a 26% increase). The weighted average tariff is still low, but it has risen over the past few years despite the new trade agreement.

The overall message is therefore that the EU is pushing landmark deals, such as the one with Japan, but at the same time is becoming more inward-looking and protectionist itself. Thus, while the EU-Japan EPA certainly contributes to reaffirming the EU as an active player in the world of international trade that is able to conclude important trade agreements, there are other actions that continue damaging the EU’s credibility as a defender of the liberal international economic order.

Conclusions

The EU-Japan EPA is one of the largest FTAs ever signed and ratified. Both parties benefit economically while the effects on outsiders are very small. However, the more important point about the EPA is that it sends a strong signal in favour of a rules-based international order that places cooperation and a positive-sum logic above a transactional zero-sum approach.

While the agreement is an achievement to celebrate, one should not shy away from some sobering facts that invite further action. First, the agreement covers a very substantial share of world GDP but it will very soon be overtaken by yet bigger regional trade agreements. Secondly, the parties must continue to work on innovative rules for global governance. This is particularly true in the areas of investment and data flows.

Gabriel Felbermayr

Director, ifo Center for International Economics | @GFelbermayr

References

Baldwin, R., & F. Robert-Nicoud (2015), ‘A simple model of the Juggernaut effect of trade liberalisation’, International Economics, nr 143, p. 70-79.

Benz, S., & E. Yalcin (2015), ‘Productivity versus employment: quantifying the economic effects of an EU-Japan Free Trade Agreement’, The World Economy, nr 38, p. 935-961.

Cabinet Office of Japan (2017), ‘Economic analysis on the impact of Japan-EU EPA (Nichi- EU EPA tou no Keizai Kouka Bunseki)’, technical report, Cabinet Office of Japan.

Chowdhry, S., A. Sapir & A. Terzi (2018), ‘The EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement’, European Parliament.

Dreyer, I. (2018), ‘EU-Japan EPA text analysis – Easy on the ambition?’.

European Commission (2016), ‘Trade sustainability impact assessment of the Free Trade Agreement between the European Union and Japan, Final Report’, technical report, European Commission.

European Commission (2018), ‘The economic impact of the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA)’.

Felbermayr, G., F. Kimura, T. Okubo & M. Steininger (2019), ‘Quantifying the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement’, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, forthcoming.

Kawasaki, K. (2017), ‘Emergent uncertainty in regional integration – Economic impacts of alter-native RTA scenarios’, GRIPS Discussion Paper nr 16-27.

Sunesen, E., J. Francois & M. Thelle (2010), ‘Assessment of barriers to trade and investment between the Eu and Japan. Final report prepared for the European Union (DG Trade)’, technical report.

Viner, J. (1950), The Customs Union Issue, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, New York.