Theme

The ‘dark side’ of digital diplomacy, that is, the strategic use of digital technologies as tools to counter disinformation and propaganda by governments and non-state actors has exploded in the recent years thus putting the global order at risk.

Summary

The ‘dark side’ of digital diplomacy, that is, the strategic use of digital technologies as tools to counter disinformation and propaganda by governments and non-state actors has exploded in the recent years thus putting the global order at risk. Governments are stepping up their law enforcement efforts and digital counterstrategies to protect themselves against disinformation, but for resource-strapped diplomatic institutions, this remains a major problem. This paper outlines five tactics that, if applied consistently and with a strategic compass in mind, could help MFAs and embassies cope with disinformation.

Analysis

Like many other technologies, digital platforms come with a dual-use challenge that is, they can be used for peace or war, for good or evil, for offense or defence. The same tools that allow ministries of Foreign Affairs and embassies to reach out to millions of people and build ‘digital’ bridges with online publics with the purpose to enhance international collaboration, improve diaspora engagement, stimulate trade relations, or manage international crises, can be also used as a form of “sharp power” to “pierce, penetrate or perforate the political and information environments in the targeted countries”, and in so doing to undermine the political and social fabric of these countries.1 The “dark side” of digital diplomacy, by which I refer to the strategic use of digital technologies as tools to counter disinformation and propaganda by governments and non-state actors in pursuit of strategic interests, has expanded in the recent years to the point that it has started to have serious implications for the global order.2

For example, more than 150 million Americans were exposed to the Russian disinformation campaign prior to the 2016 presidential election, which was almost eight times more the number of people who watched the evening news broadcasts of ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox stations in 2016. A recent report prepared for the U.S. Senate has found that Russia’s disinformation campaign around the 2016 election used every major social media platform to deliver words, images and videos tailored to voters’ interests to help elect President Trump, and allegedly worked even harder to support him while in office.3 Russian disinformation campaigns have also been highly active in Europe4, primarily by seeking to amplify social tensions in various countries, especially in situations of intense political polarisation, such as during the Brexit referendum, the Catalonian separatist vote5, or the more recent “gilets jaunes” protests in France.6

Worryingly, the Russian strategy and tactics of influencing politics in Western countries by unleashing the “firehose of falsehoods” of online disinformation, fake news, trolling, and conspiracy theories, has started to be imitated by other (semi)authoritarian countries, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Philippines, North Korea, China, a development which is likely to drive more and more governments to step up their law enforcement efforts and digital counter-strategies to protect themselves against the ‘dark side’ of digital diplomacy.7 For resource-strapped governmental institutions, especially embassies, this is clearly a major problem, as with a few exceptions, many simply do not simply have the necessary capabilities to react to, let alone anticipate and pre-emptively contain a disinformation campaign before it reaches them. To help embassies cope with this problem, this contribution reviews five different tactics that digital diplomats could use separately or in combination to counter digital disinformation and discusses the possible limitations these tactics may face in practice.

Five counter-disinformation tactics for diplomats

Tactic #1: Ignoring

Ignoring trolling and disinformation is often times the default option for digital diplomats working in embassies and for good reasons. The tactic can keep the discussion focused on the key message, it may prevent escalation by denying trolls the attention they crave, it can deprive controversial issues of the ’oxygen of publicity’, and it may serve to psychological protect digital diplomats from verbal abuse or emotional distress. The digital team of the current U.S. Ambassador in Russia seems to favour this tactic as they systematically steer away from engaging with their online critics (see Fig 1, the left column). This approach stands in contrast with the efforts of the former Ambassador, Michael McFaul, who often tried to engage online with his followers and to explain the position of his country on various political issues to Russian audiences, only to be harshly refuted by the Russia Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) or online users (see Fig 1, the right column).

At the same time, one should be mindful of the fact that the ignore tactic may come at the price of letting misleading statements go unchallenged, indirectly encouraging more trolling due to the perceived display of passivity and of missing the opportunity to confront a particular damaging story in its nascent phase, before it may grow into a full-scale, viral phenomenon with potentially serious diplomatic ramifications.

Tactic #2: Debunking

In the post-truth era, fact-checking is “the new black” as the manager of the American Press Institute’s accountability and fact-checking program neatly described it.8 Faced with an avalanche of misleading statements, mistruths and ‘fake news’ often disseminated by people in position of authority, diplomats, journalists and the general public require access to accurate information in order to be able to take reliable decisions. It makes thus sense for embassies and MFAs to seek to correct false or misleading statements and to use factual evidence to protect themselves and the policies they support from deliberate and toxic distortions. The #EuropeUnited campaign launched by the German MFA in June 2018 in response to the rise of nationalism, populism and chauvinism, is supposed to do exactly that: to correct misperceptions and falsehoods spread online about Europe by presenting verifiable information about what European citizens have accomplished together as members of the European Union.9Fig 2: #EuropeUnited campaign by the German MFA

„Our answer to ‚America First’ can only be #EuropeUnited.“ Foreign Minister @HeikoMaas on the US decision to impose punitive #tariffs on #steel and #aluminum. pic.twitter.com/B8HKzhPkVu— Germany in the EU (@GermanyintheEU) 31 de mayo de 2018

Desinformation ist eine große Herausforderung, die Staaten nicht alleine lösen können. Für EU-weites ?? Engagement bildet der “Aktionsplan gegen Desinformation”, der gestern angenommen wurde, eine sehr gute Basis. @eu_eeas #EuropeUnited https://t.co/lr5SWIXEqx— Auswärtiges Amt (@AuswaertigesAmt) 14 de diciembre de 2018

Source: @GermanyintheEU and @AuswaertigesAmt on Twitter.

The key question, however, is whether fact-checking actually works and if so, under what conditions? Research shows that misperceptions are widespread, that elites and the media play a key role in promoting these false and unsupported beliefs10, and that false information actually outperforms true information.11 Providing people with sources that share their point of view, introducing facts via well-crafted visuals, and offering an alternate narrative rather than a simple refutation may help dilute the effect of disinformation, alas not eliminate it completely. While real-time fact checks can reduce the potential for falsehoods to ‘stick’ to the public agenda and go viral, direct factual contradictions may actually strengthen ideologically grounded beliefs as disinformation may make those exposed to it extract certain emotional benefits.12 This is why using emotions in addition to facts may prove a more effective solution for countering online disinformation, although the right format of fact-based emotional framing arguably varies with the context of the case and the profile of the audience.

Tactic #3: Turning the tables

The jiu-jitsu principle of turning the opponent’s strength into a weakness may also work well when applied to the case of counter-disinformation strategies. The use of humour in general, and of sarcasm in particular, could be reasonably effective for enhancing the reach of the message, deflecting challenges to ones’ narrative without alienating the audience, avoiding emotional escalation, and undermining the credibility of the source.13 The case of the Israeli embassy in the US using a “Mean Girls” meme in June 2018 to confront Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s hateful tweet about Israel being “malignant cancerous tumour” that “has to be removed and eradicated” is instructive: it was widely shared and praised on social media and proved effective in calling attention to Israel’s plea for a harsher international stance towards Iran. In a slightly different note, the sarcastic tweet of the joint delegation of Canada at NATO in Aug 2014 poking fun at the statements of the Russian government about is troops entering Crimea by “mistake”, showcased Canada’s commitment to European security and the NATO alliance and further undermined the credibility of Kremlin in the eyes of the Western public opinion.Fig 3: Using humour to discredit opponents and their policies

Our stance against Israel is the same stance we have always taken. #Israel is a malignant cancerous tumor in the West Asian region that has to be removed and eradicated: it is possible and it will happen. 7/31/91#GreatReturnMarch— Khamenei.ir (@khamenei_ir) 3 de junio de 2018

Geography can be tough. Here’s a guide for Russian soldiers who keep getting lost & ‘accidentally’ entering #Ukraine pic.twitter.com/RF3H4IXGSp— Canada at NATO ?? (@CanadaNATO) 27 de agosto de 2014

Source: @khamenei_ir, @IsraelinUSA and @CanadaNATO on Twitter.

While memetic engagement is attracting growing attention as a possible tool for countering state and non-state actors in the online information environment, one should also bear in mind the potential risks and limitations associated with this tactic.14 It is important, for instance, to understand well the audience, not only for increasing the effectiveness of the memetic campaign, but more critically for avoiding embarrassing situations when the appeal to humour may fall flat or even backfire thus undermining one’s own narrative and standing. The overuse of memes and humour may also work against public expectations of diplomatic conduct, which generally revolve around associations with requirements of decorum, sobriety and gravitas. Most importantly, memetic engagement should not be conducted loosely, for entertaining the audience, but with some clear objectives in mind about how to enhance the visibility of your positions or policies and/or undermine those of the opponent.

Tactic #4: Discrediting

A stronger version of the jiu-jitsu principle mentioned above is the tactic of discrediting the opponent. The purpose in this case is not to undermine the credibility of the message, but of the messenger itself so that the audience will come to realise that whatever messages come from a particular source, they cannot be trusted. This tactic should be considered very carefully, and should be used only in special circumstances, as it would most likely lead to an escalation of the online info dispute and would probably trigger a harsh counter-reaction from the opponent. The way in which this tactic may work is by turning the opponent’s communication style against itself: amplifying contradictions and inconsistencies in his/her message, exposing the pattern of falsehoods disseminated through his/her channels of communication, and maximising the impact of the counter-narrative via the opponent’s ‘network of networks’.Fig 4: FCO campaign to discredit Russian MFA as a credible source

The nerve agent came from Sweden,

Ukraine did it to frame Russia,

It was contamination from the UK’s own research facility…

Instead of providing an explanation for the Salisbury incident, Russia has launched a campaign of disinformation pic.twitter.com/dZQMXgnAFp— Foreign Office ?? (@foreignoffice) 20 de marzo de 2018

Source: @foreignoffice on Twitter.

Following the failed assassination attempt of Sergei Skripal and his daughter in March 2018, pro-Kremlin accounts on Twitter and Telegram started to promote a series of different conspiracies and competing narratives, attached to various hashtags and social media campaigns, with the goal, as one observer noted, to confuse people, polarise them, and push them further and further away from reality.15 In response to this, the FCO launched a vigorous campaign in which it took advantage of the Russian attempt to generate confusion about the incident by forcefully making the point that the 20+ different explanations offered by Kremlin and Russian sources, including the story that the assassination might have been connected to Mr Skripal’s mother in law, made absolutely no sense and therefore whatever claim Russian sources might make, they could be trusted. While the campaign proved effective in further undermining the credibility of Kremlin as a trustworthy source and convincing partners to back up U.K.’s position in international fora, it should nevertheless be noted that the bar set by Russian authorities after the invasion of Crimea and the shooting down of MH17 was already low. In addition, while the tactic of discrediting the opponent may work well to contain its influence online, it may do little to deter him/her from engaging in further disinformation as long as the incentives and especially the costs for pursuing this strategy remain unaltered.

Tactic #5: Disrupting

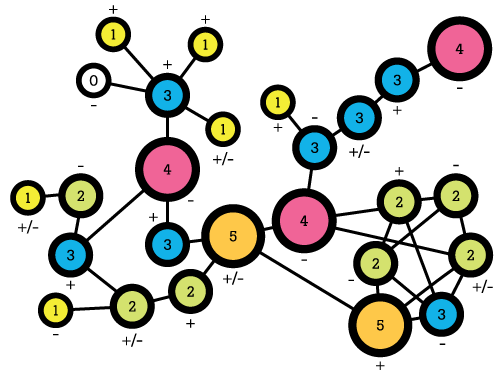

One way in which the costs of engaging in disinformation could be increased is by disrupting the network the opponent uses for disseminating disinformation online. This would imply the mapping of the network of followers of the opponent, the tracing of the particular patterns by which disinformation is propagated throughout the network, and the identification of the gatekeepers in the network who can facilitate or obstruct the dissemination of disinformation (e.g., nodes 4 and 5 in the network described in Fig 5). Once this accomplished, the disruption of the disinformation network could take place by targeting gatekeepers with factual information about the case, encouraging them not to inadvertently promote ‘fake news’ and falsehoods, and in extreme situations by working with representatives of digital platforms to isolate gatekeepers who promote hate and violence.

The Israeli foreign ministry has been one of the MFAs applying this tactic, in this case for stopping the spread of anti-Semitic content. Accordingly, the ministry starts first by identifying gatekeepers and ranking them by their level of online influence.16 It then begins approaching and engaging with them online, with the purpose of making them aware of the fact that they sit an important junction of hate speech. The ministry then attempts to cultivate relationships with these gatekeepers so that they may refrain from sharing hate content online. In so doing, the ministry can effectively manage to contain or quarantine online hate networks and prevent their malicious content from reaching broader audience.

If properly implemented, this tactic could indeed significantly increase the costs of disseminating disinformation as opponents need to constantly protect and by case to rebuild their network of gatekeepers. They may also have to frequently re-configure the patterns by which they disseminate disinformation to their target audiences. At the same time, this tactic requires specialised skills for successful design and implementation, which might not be available to many embassies or even MFAs. The process of engineering the disruption of the disinformation network also prompts important ethical questions about how to make sure this tactic is not abused for stifling legitimate criticism of the ministry or the embassy.

Conclusions

As argued elsewhere, digital disinformation against Western societies works by focusing on exploiting differences between EU media systems (strategic asymmetry), targeting disenfranchised or vulnerable audiences (tactical flexibility), and deliberately masking the sources of disinformation (plausible deniability). The five tactics outlined in this paper may help MFAs and embassies better cope with these challenges if applied consistently and with a strategic compass in mind. Most importantly, they need to be carefully adapted to the context of the case in order to avoid unnecessary escalation. Here are ten questions that may help guide reflection about how to decide what tactic is appropriate to use and in what context:

- What type of counter-reaction would reflexively serve to maximise the strategic objectives of the opponent?

- What are the risks of ignoring a trolling attack or disinformation campaign?

- What type of disinformation has the largest potential to have a negative political impact for the embassy or the MFA?

- To what extent giving the “oxygen of publicity” to a story will make the counter-reaction more difficult to sustain?

- What audiences are most open to persuasion via factual information? What audiences are less open to be convinced by facts?

- What type of emotions resonate with the audience in specific contexts and how to invoke them appropriately as a way of introducing factual information?

- What type of humor works better with the target audience and how to react to situations when humor is used against you?

- How best to leverage the contradictions and inconsistencies in the opponent’s message without losing the moral ground?

- Who are the gatekeepers in the opponent’s network of followers and to what extent can they be convinced to refrain from sharing disinformation online?

- Under what conditions is reasonable to escalate from low-scale counter-reactions (ignoring, debunking, ‘turning the tables’) to more intense forms of tactical engagement (discrediting, disrupting)?

Corneliu Bjola

Head of the Oxford Digital Diplomacy Research Group (#DigDiploROx) | @CBjola

1 Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig, “The Meaning of Sharp Power”, Foreign Affairs, November 26, 2017.

2 “The dark side of digital diplomacy”, in Countering Online Propaganda and Extremism, Corneliu Bjola and James Pamment (Eds.), Routledge (2018).

3 Craig Timberg and Tony Romm, ‘New Report on Russian Disinformation, prepared for the Senate’, The Washington Post, December 17, 2018.

4 Corneliu Bjola and James Pamment, “Digital containment: Revisiting containment strategy in the digital age”, Global Affairs, Volume 2, 2016.

5 Robin Emmott, ‘Spain sees Russian interference in Catalonia’, Reuters, November 13, 2017.

6 Carol Matlack and Robert Williams, ‘France Probe Possible Russian Influence on Yellow Vest Riots’, Bloomberg, December 8, 2018.

7 Daniel Funke, ‘A guide to anti-misinformation actions around the world’, Poynter, October 31, 2018.

8 Jane Elizabeth, ‘Finally, fact-checking is the new black’, American Press Institute, September 29, 2016.

9 Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, ‘Courage to Stand Up for Europe’, Federal Foreign Office, June 23, 2018.

10 D.J. Flynn, Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler, ‘The Nature and Origins of Misperceptions’, Dartmouth College, October 31, 2016.

11 Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Rai and Sinan Aral, ‘The spread of true and false news online’, Science, Volume 359, March 9, 2018.

12 Jess Zimmerman, ‘It’s Time to Give Up on Facts’, Slate, February 8, 2018.

13 Stratcom laughs: in search of an analytical framework, NATO Stratcom, March 17, 2017.

14 Vera Zakem, Megan K. McBride and Kate Hammerberg, ‘Exploring the Utility of Memes for U.S. Government Influence Campaigns’, Center for Naval Analyses, April 2018.

15 Joel Gunten and Olga Robinson, ‘Sergei Skripal in the Russian disinformation game’, BBC News, Sep. 9, 2018.

16 Ilan Manor, ‘Using the Logic of Networks in Public Diplomacy’, Centre on Public Diplomacy Blog, Jan. 31, 2018.