paper is jointly published with

Theme

What are the prospective implications of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) on Pakistani development and regional stability?

Summary

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor provides an excellent opportunity for improving the economic and security situation in Pakistan and its neighbouring countries. However, such an outcome cannot be taken for granted. This paper analyses the steps that should be taken to favour this scenario and warns about the consequences that a poorly-managed implementation of the CPEC might have, such as aggravating divisions within Pakistan and heightening tensions between Islamabad and other regional players.

Analysis1

Since its announcement in July 2013, probably no policy initiative is receiving more attention in Pakistan than the CPEC. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has reiterated on several occasions that CPEC could be a game changer for Pakistan and the entire region.2 Along the same lines, Wang Yi, China’s Foreign Minister, has described the CPEC as the ‘flagship project’ of the One Belt, One Road initiative,3 Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy project.4 Moreover, there is a widespread consensus among the Pakistani military, political parties and society at large on the enormous potential of the CPEC for spurring economic growth in the country.

Indeed, the US$46 billion package of projects contained in the CPEC offers an exceptional opportunity to Pakistan for tackling some of the main barriers hindering its economic development: energy bottlenecks, poor connectivity and limited attraction for foreign investors. According to the Agreement on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Energy Project Cooperation between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, signed on 8 November 2014, 61% of the CPEC investment will be allocated to energy projects aiming to improve energy-system capacity and the transmission and distribution network. Thus, Pakistan may be able to terminate with what a Wilson Centre report labelled ‘Pakistan’s Interminable Energy Crisis’,5 which according to their estimates has cost its economy 2% to 2.5% of GDP annually. Only in the early harvest phases (2017-18), CPEC projects are expected to add 10,400MW to the Pakistani energy system.

Up to 36% of CPEC funding will be devoted to infrastructure, transport and communication. It is evident that a greater connectivity will create new opportunities for development in Pakistan, since, according to the Planning Commission, the poor performance of transport sector costs the Pakistani economy 4% to 6% of GDP every year.6 The improvement in communications will be important both for a greater integration of the domestic market and for facilitating Pakistani exports. In addition, the CPEC will help to improve the confidence of international investors in Pakistan, whose image of the country is not always in line with current situations and tends to be more negative than merited by actual conditions. In the words of the former Economic Minister of the Pakistani Mission to the EU, Safdar Sohail, ‘Pakistan has turned a page in terms of terrorism and regional integration and the Chinese investment is a way of sending that message’.

Obstacles

The massive prospective benefits that the CPEC can bring to Pakistan are contingent to its actual implementation, which faces serious obstacles. One of the most obvious is the security situation, despite the improvements experienced on that front during the past two years. The most well-known pro-independence Baloch leaders have denounced the negative impact they believe CPEC will have in Balochistan and some have even warned China ‘to stay away from Gwadar’.7 Beijing’s concerns on this issue made the Pakistani authorities announce, during Xi Jinping’s visit to Islamabad in April 2015, the creation of a 12,000-strong force devoted to protecting Chinese interests and nationals in Pakistan.8 This new Special Security Division is funded by Pakistan, although certain well-informed sources have suggested that China will provide some equipment. Moreover, Rs45 billion is expected to be spent in fiscal year 2016 on raising the security unit and on Operation Zarb-e-Azb.9 This is a key issue, since Beijing has become more sensitive over the past years to attacks against Chinese nationals on foreign soil.

The CPEC’s security is also closely interlinked with regional geopolitics, particularly with India’s stance on the initiative and on the stabilisation of Afghanistan. In India many voices have raised concerns about the CPEC, and even the Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, criticised the project as ‘unacceptable’ during his visit to Beijing in June 2015.10 Indian reservations are mainly related to certain CPEC transport projects crossing Gilgit-Baltistan, part of the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir, and the implications of China’s easier access to the Indian Ocean and how they might affect India’s security and strategic context.11 Various quarters in Pakistan believe that these misgivings have even led to cooperation between Indian security agencies and Pakistani militants, especially following the arrest in Balochistan in March 2016 of an alleged officer of the Research and Analysis Wing.12

This is not to deny that the CPEC can offer incentives for India to improve its relations with Pakistan, since the corridor could facilitate Indian access to Central Asia.13 In other words, the CPEC is not only threatened by security conditions within and without Pakistan, but can also contribute to improving them. The potential contribution of the CPEC to regional stability is more evident at present with regard to Afghanistan. Peace in Afghanistan is a key factor for the success of the CPEC and the reduction of international support for the East Turkestan Independent Movement militants. These are the main reasons of Chinese decision to participate in a joint effort with the governments of the US, Pakistan and Afghanistan to revive the Afghan peace process.14 This direct Chinese involvement in seeking a political settlement to the war in Afghanistan contrasts with Beijing’s avowed policy of non-interference before launching the One Belt, One Road initiative.

Another difficulty is the lack of experience in mutual economic cooperation, since Pakistani-Chinese relations have been traditionally limited to political and military factors. This scant economic interaction is illustrated by trade and investment figures. The value of bilateral trade was below US$1 billion until 2001 and China ranked among the three main foreign investors in Pakistan during only one fiscal year (2006/07) in the previous decade.15 Therefore, it can be argued that the CPEC incorporates an economic pillar to this long and consolidated bilateral relationship and both sides are now learning how to co-operate in this field.

Scenarios

The CPEC consists of three layers including early harvest, medium term and long term projects. First two stages are in working position, whereas the long-term project will end till 2030. At the moment it is at an early phase, and its projects are expected to be completed in 2017 and 2018. This is the first of the four phases that make up the CPEC, the other three being the short-term (2020), medium-term (2025) and long-term (2030) phases. At the outset it would be difficult to assess CPEC’s impact on Pakistan, however this should be borne in mind that this is the most pertinent question with far reaching consequences.

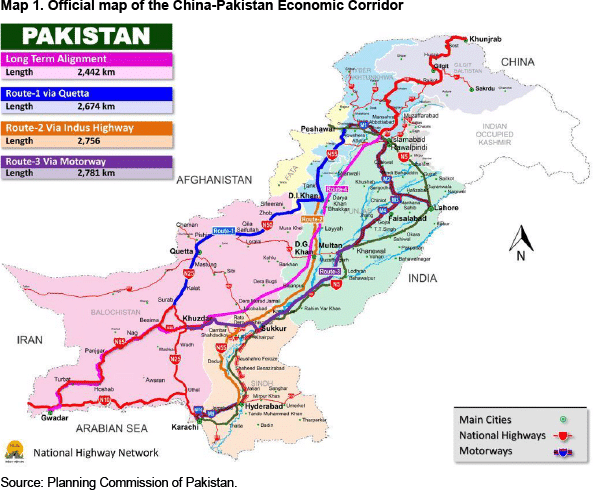

It could be argued that even if the China-Pakistan corridor has been officially described as an economic corridor, its final nature is still far from being determined and will depend to a large extent on decisions made in Beijing and Islamabad. Three different scenarios can be envisioned: (1) a transit corridor; (2) an economic corridor; and (3) a development corridor. The China-Pakistan corridor influence on the socio-economic development of Pakistan will be determined by the kind of corridor it will become. Since Pakistan is a diverse country and the CPEC will have several different alignments (see Map 1) running through different areas, it is quite possible that its influence will vary from one area to another.

Transit corridor

A transit corridor connecting China’s western province of Xinjiang with the Indian Ocean port of Gwadar in south Balochistan was first proposed in 2006 by the then President General Pervez Musharraf.16 The corridor’s completion would serve Beijing’s interests in many ways. On the economic front, the cost of western and central China’s international trade with Central Asia, the Middle East, Europe and Africa will be reduced. For instance, China would save around US$2 billion every year if it were to use the CPEC to import 50% of its current volume of oil supplies.17 In addition, better connectivity and easier sea access will favour the development of Xinjiang, which the Chinese authorities considers as paramount for reducing terrorism in the region. Moreover, the transit corridor has significant geostrategic value, making China less vulnerable to US rebalancing towards Asia and an eventual blockade of the Malacca Strait. It will also facilitate the projection of China’s influence in the Indian Ocean and in Eurasia.18 Therefore, both the maritime and the land silk roads are expected to converge in the port of Gwadar.

If the CPEC is finally merely a transit corridor, its potential for fostering socioeconomic development in Pakistan will be severely limited. Even if China is offering financing through the CPEC to Pakistan in a volume and under conditions unmatched by other creditors, these are loans, not grants, and therefore Pakistan will be expected to repay them.19 The total value of China’s loans has not been disclosed, but should be quite significant, since the US$11 billion granted for infrastructure purposes will be added as a substantial share of the US$35 billion investment announced for the power sector. For instance, US$820 million of the US$2 billion committed for the Thar coal project are provided by a syndicate of Chinese banks, including the China Development Bank, the Construction Bank of China and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.20

The massive transport facilities that are being – and shall be – created, extended and renovated within the framework of the CPEC will demand a notable disbursement in security and maintenance once they are completed. Security will be particularly problematic in the western alignment, as will maintenance under the severe weather and geographical conditions of the Pakistani side of the Karakorum Highway and of Balochistan. This may aggravate by its expected heavy use by lorries.

The growing Pakistani exports, the development of roadside services and transit fees could offset these financial obligations. Traditional exports such as textiles, agro-food, sporting-goods and mining are likely to benefit from the improvements in connectivity. However, more detailed sectoral analyses are needed, since some areas of the Pakistani economy, mainly the manufacturing industry, could suffer due to higher Chinese competition brought on by the CPEC. It also demands more exhaustive studies to be conducted in order to gain enough information to embark precisely on the cost-benefit analysis that should inform CPEC-related decisions: for instance, the feasibility of transit fees for Chinese oil shipments and trade traffic and the eventual volume of income they could generate.

Economic corridor

Unlike transit corridors, economic corridors are explicitly designed to stimulate economic development. In order to overcome its energy crisis, Pakistan needs to articulate an industry and trade boosting programme to gain from the CPEC in terms of additional business opportunities, apart from temporary jobs. The fact that the lion’s share of CPEC-related investment will be allocated to projects in the energy sector, to help Pakistan overcome its chronic energy crisis, is a solid indication that the China-Pakistan corridor honours its official designation as an economic corridor. Most of the energy projects are being financed under a build-own-operate model. In this scenario, Chinese investors are entering the Pakistani energy market as independent power providers with special protection guarantees. Chinese independent power-providers are assured an 18% return on their investment, whereas the rest are getting a 17% return for their equity; and some complain that this would distort the level playing field. This, like the establishment of exclusive Chinese special economic or industrial zones should be managed with extreme caution in order to avoid potential sinophobic feelings that might hinder the implementation of the CPEC. In any case, if the energy projects are implemented and the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority is able to set prices that are acceptable to investors and consumers, the spillover effect on the Pakistani economy will be colossal.

How the CPEC favours the mobilisation of Pakistan’s industry and trade sectors is not clear at present. The Government of Pakistan has proposed the creation of 29 industrial parks and 21 mineral zones, 27 of them to be granted the status of Special Economic Zones (SEZ).21 The most advanced of these projects is the 9 km2 Gwadar SEZ, expected to be fully functional by the end of 2017 , which will accommodate industrial units for mines and minerals, food processing, agriculture, livestock and energy.22 It is hoped that these initiatives might attract Chinese investment, technology and know-how, which will translate into greater and more diversified Pakistani exports. The two projects, joint cotton biotech laboratory and a joint marine research centre, which are already agreed upon can contribute to achieve these objectives.23

However, the traditional perception in the Pakistani business community is that Chinese investors are neither interested in investing in Pakistan as an export base nor in generating profits from Pakistan through joint ventures of private foreign ownership.24 Indeed, Pakistan-China Industrial Cooperation Committee is not yet established and the absence of concrete financial commitments for most of the announced industrial parks and mineral zones are not very promising signs.

Development corridor

There are three routes (Western, Central and Eastern) of the CPEC, after it enters Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa from the Khunjerab Pass and Gilgit-Baltistan. Through the first (Western) route the CPEC will enter Balochistan via Dera Ismail Khan to Zhob, Qila Saifullah, Quetta, Kalat, Punjgur, Turbet and Gwadar. The second (Central) route goes from Dera Ismail Khan to Dera Ghazi Khan and onwards to Dera Murad Jamali, Khuzdar, Punjgur, Turbet to Gwadar. The third route (Eastern) enters the Punjab province from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, going through Lahore, Multan and Sukkur, from there it takes the traditional highway to enter Balochistan, passing through Khuzdar, Punjgur, Turbet and Gwadar. An alternate route is to go from Sukkur to Karachi and from there take the coastal highway to Gwadar.25 It is important to adopt additional measures to so that all the regions of the country reap the gains from CPEC.

It is generally believed that in the early project stage priority is given to the eastern route at the expense of the western one and to local conglomerates such as the Dawood Group at the expense of small and medium enterprises.26 In this scenario, it is believed that CPEC could lead to growing inequality and materialise into local discontent. Therefore, additional measures are needed to make the most out of the CPEC and to ensure that the economic opportunities opened up by the initiative should translate into development opportunities for wide strata of Pakistan’s population and help foster a more cohesive country. There are great expectations throughout Pakistan on the potential benefits of the CPEC, but if no sense of ownership is given to local governments and communities the situation could change. Influential voices, such as, Maulana Fazlur Rehman, the leader of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, initially criticised the CPEC assuming that the project would not benefit their constituencies.27 These precedents require a more committed participation by local actors in the CPEC through consultation and engagement.

To address these reservations, the Federal Government and major political parties in a meeting on May 28, 2015 discussed these routes and agreed to build the first route, which is the shortest, on a priority basis. This route passes through very underdeveloped areas that have security problems. However, road building and infrastructure development in these areas will contribute to their socio-economic development.28 Moreover, under the principle of ‘One Corridor, Multiple Passages’, diffusing the controversy, the Pakistani leadership reaffirmed that there would be multiple options for transportation through different roads but Western alignment of the corridor passing from Balochistan and KP would be completed on priority basis. The deadline set for the completion is July 16, 2018. It is important to note that it will be a four-lane road in the first phase to be upgradeable to a six-lane motorway. It was also agreed that sites of economic zones would be finalised in consultation with provinces and facilities required for these zones would be a shared responsibility of federal and provincial governments. The main critic of different aspect of CPEC, the Chief Minister of Khyber Pakhtunnkhwa, Pervaiz Khattak, ‘I am not at all against any route and all routes will bring prosperity to Pakistan’.29

Another key measure is investing in education in order to entitle local communities to exploit the opportunities that CPEC offers. Even if the infrastructure, logistics and regulatory framework are right, industrial parks will demand skilled workers. Establishing vocational schools is an excellent way to increase the educational improvement of the local labour force. Although this point is not completely neglected, as US$10 million Pakistani-Chinese technical and vocational institute is scheduled to open its doors in Gwadar by December 2017, a bigger commitment on this front would be very welcome. Furthermore, the Federal government should also provide industrial policies and commerce and trade experts to provincial governments to develop local capacities in these areas and avoid a disconnection between the policies of the central government and local economic sectors. Meanwhile, the financial sector should give more attention to small and medium-sized enterprises, which faces difficulties in obtaining finance in Pakistan.

The implementation of these measures in Pakistan’s less developed areas (such as Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) participating in the CPEC, would not only improve the living standards of the local populations but would bring about enormous gains for Pakistan in terms of security and stability. This will ensure the social and economic wellbeing of the people who have to endure very harsh living conditions in certain backward areas –in some cases there is a roughly 50% prevalence of malnutrition in children and the expansion of the militant economy where the military is conducting operations against the militants–. New economic opportunities could help reduce criminal activity and make local communities into stakeholders in the success of the CPEC and therefore make them more willing to ensure security.

Conclusions

The CPEC provides an opportunity to reinvigorate Pakistan’s economic structure, particularly through the development of its energy sector and by fostering a greater connectivity. Unfortunately, the huge potential of the CPEC for promoting socioeconomic development in Pakistan has sometimes led to over expectations and to an uncritical approach to the project. The CPEC is at a very early stage and it is impossible to confirm at present the actual impact of the project. In this context, this paper presented different scenarios of the eventual impact of CPEC on Pakistan in order to promote a debate on ways and means to maximise its benefits in terms of prosperity and stability.

Should the CPEC become a development corridor for most of Pakistan it would increase employment generation, alleviate poverty, help to maintain law and order by engaging youth in commercial activities and improve the socioeconomic outlook and indicators. Strengthening the weak links between Pakistan’s domestic commerce and its exports should boost both exports and investment, and foster innovation in products and services. All of this would significantly increase the country’s GDP and have a multiplier effect on taxation besides making room for increased expenditure on social sectors such as education, health and basic amenities. In this context, the CPEC could even contribute to improving security in Pakistan, indirectly through incentives for regional stability and better relations with India, and directly through development opportunities for Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Such an ideal scenario is by no means guaranteed. The CPEC can not only mitigate some of the main barriers hindering Pakistan’s economic development but also increase its already heavy external debt. Greater transparency is essential to allow a detailed cost-benefit analysis that at present is not possible. The State Bank’s Governor has publicly asked for details on the structure of the CPEC’s deals, which is essential to fulfilling his duty as the supervisor of the country’s macroeconomic stability. To bridge the gap between the most and the least developed regions of Pakistan, a greater implication of Pakistani society and comprehensive measures to increase local capacities in vulnerable regions are needed.

Furthermore, taking into account that the CPEC is the most advanced part of the Belt and Road Initiative, it might be possible to acquire a deeper understanding of the New Silk Road by looking at how the CPEC develops and impacts Pakistan and its neighbouring countries.

Mario Esteban

Senior Analyst, Elcano Royal Institute | @wizma9

1 This paper is jointly published by the Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI) and the Elcano Royal Institute. The author would like to thank the ISSI for its support during his fieldwork in Pakistan.

2 Game changer: All provinces will reap benefits of CPEC, says PM, The Express Tribune.

3 People-to-People, Political and Parliamentary Exchanges to induce impetus to existing warms Pak-China Relationship: Sardar Ayaz Sadiq, National Assembly of Pakistan.

4 Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, National Development and Reform Commission of China.

5 Pakistan’s Interminable Energy Crisis: Is There Any Way Out?, Wilson Center.

6 Connectivity, Framework for Economic Growth, Pakistan.

7 Only American Guarantees Acceptable in Baloch-Islamabad Conflict Resolution: Brahumdagh Bugti, The Baloch Hal; China Pakistan Economic Corridor: Ultimate loser is Balochistan, News Bharati.

8 Economic corridor: 12,000-strong force to guard Chinese workers, The Express Tribune.

9 Budget 2016 preview: For every rupee paid in taxes, 26 paisas will go to defence, The Express Tribune.

10 China-Pakistan Economic Corridor ‘unacceptable’, Modi tells China, The Express Tribune.

11 The Need for Haste on Pakistan-occupied Kashmir: China Pakistan Economic Corridor Needs a Counter Strategy, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses.

12 India accepts ‘spy’ as former navy officer, denies having links, Dawn.

13 The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: India’s Options, Institute of Chinese Studies (ICS).

14 What does China want from the Afghan peace process?, DW.

15 Fazal-ur-Rahman, Pakistan-China trade and investment relations.

16 Musharraf vows to make Pakistan energy corridor for China, Economic and Commercial Counsellor’s Office of the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

17 PRIME Institute (2015), China Pakistan Economic Corridor: A Primer.

18 http://opinion.huanqiu.com/opinion_world/2012-10/3193760.html.

19 The loans include both concessional and commercial credit at an interest rate ranging from 1% to 3% and from 5% to 6%, respectively.

20 Thar coal project achieves $2bn financial close after govt guarantee, Dawn.

21 Govt proposes 29 industrial parks, 21 mineral zones under CPEC, The News; 12 sites proposed for special economic zones in Balochistan, K-P, The Express Tribune.

22 Gwadar to get first SEZ under CPEC, Dawn.

23 Biotech research to be established by China in Pakistan, The Nation.

24 Fazal-ur-Rahman, Pakistan-China trade and investment relations.

25 Hasan Askar Rizvi, The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Regional Cooperation and Socio-Economic Development.

26 Western route of CPEC to be completed by 2018, Dawn, and List of Agreements/MoUs Signed during visit of Chinese President.

27 The long road: Politicians warn of disharmony over CPEC, The Express Tribune.

28 Hasan Askar Rizvi, The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Regional Cooperation and Socio-Economic Development.

29 Ahmad Noorani (2014), CPEC Route Controversy Routed, 16/I/2014.

30 Pakistan should be more transparent on $46 bn China deal, state bank head says, Reuters.