Theme: The European EUFOR Chad/CAR mission, in support of humanitarian and police action for the United Nations mission in Chad and the Central African Republic,has been suspended until peace is restored to the region.

Summary: On 28 January 2008, the EU launched the EUFOR Chad/CAR operation to deploy a force in support of humanitarian and police action for the United Nations mission in Chad and the Central African Republic (MINUSTAR). Three days later, the deployment was suspended due to the clashes between government and rebel forces around N’Djamena. Designed as the EU’s most ambitious military mission following the trial run of the Artemis DRC and EUFOR RD Congo operations, the current suspension is due to circumstantial causes, but also reveals a failure to correctly read the situation and reveals that poor quality intelligence was used. Since the missions were designed outside the framework of the cross–border conflict between Chad and the Sudan and the internal armed conflict in Chad, its failures in this regard became evident even as the mission was being launched. French forces efficiently evacuated the European residents in the region, but the impasse raises more questions about the capacity of France, Europe and the United Nations to evaluate their military missions and offer solutions to security problems in a continent which lacks other external suppliers of security. This ARI describes the context in which the intervention was devised, the context in which the concept of crisis management by MINUSTAR was created and the operational plan for EUFOR Chad/CAR, as well as the chronology of clashes on the ground and the options to be considered now that the mission has been suspended: to continue with the mission as soon as the clashes cease, or to review the steps taken so as to avoid making the mission part of the problem itself.

Analysis: When analysing a conflict such as the one affecting Chad, it emerges that, in fact, it is not just one but several different conflicts which mingle and interact, as shown by the assessment of the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London (Strategic Survey 2006). Insecurity in Chad cannot be separated from the insecurity in the Sudan and the Central African Republic (CAR) and neither can the insecurity of the refugees from Darfur be separated from that of Chadians displaced as a result of crime, banditry and the power vacuum inside its borders. This complex pathology is a reflection of the country’s structural complexities. Chad ranks seventh from last in human development (170/177) of the countries analysed by the United Nations, and is the fifth most corrupt country according to Transparency International (150/156). Chad has 10 million inhabitants, half of whom are aged under 15 (many bearing weapons as child soldiers) and 35% of whom suffer from malnutrition in a country where GDP growth was five times that of China in the last few years due to oil revenues. Social fragmentation is revealed by the existence of three official languages, 120 native languages, four religions, nine ethnic groups and no less than 60 political parties.

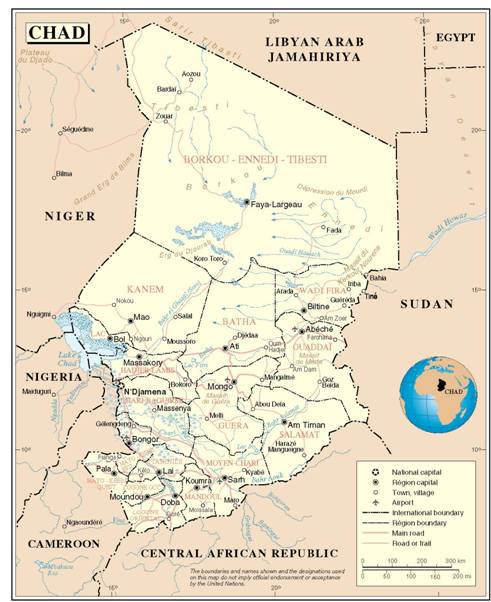

Figure 1.

Source: United Nations.

Democracy and institutions cannot flourish in a system where the Zaghawa minority has power over the remaining 97% of the population. Government, opposition, parties and rebels are virtual identities which mask ethnic, religious and regional groups linked by temporary alliances which chop and change every time one player tries to stand out above the rest. Maintaining the balance of power is a tough task indeed, when internal factionalism tends to become militarised and force is the only way to gain access to power and, more importantly, to retain it. The balance of power began to change in 2004 when petrodollars began to show up, providing the government with a scope to exert influence which it had not hitherto enjoyed. It altered again in 2005 when the current President Idriss Deby forced the constitutional system in order to enjoy a third term in office. Since then, former allies have deserted him, seeking alternatives to gain access to the power that is denied to them, and the rebels’ actions serve to both resolve the internal conflict and to foster the cross–border conflict between the Sudan and Chad.

The two governments accuse each other of supporting the rebels that harass them. N’Djamena accuses the Sudan of backing the Union of Forces for Democracy and Development (UFDD) by providing weapons and logistical support which they receive from the janjaweed militia and offering them sanctuary on the other side of the border in their attempts to overthrow President Deby. For its part, the Sudanese government accuses its Chadian counterpart, and in particular its President, of destabilising Sudanese territory by supporting the Justice and Equality Movement and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, which comprises members of his own Zaghawa ethnic group who live on both sides of the border. Rebel groups move around Darfur and cross the border between the Sudan and Chad to attack the other side either at their own initiative or under orders of one of the two governments, blurring the line between the internal and cross–border conflicts. And as if that weren’t enough, the presence of oil companies (mainly from the US, Indonesia and China) since early 2000 makes energy a frontline issue (the Doba oil fields make Chad Africa’s eighth–largest oil producer, at 249,000 barrels per day, while the Sudan is its sixth–largest, at 363,000). Oil revenues, far from alleviating the situation of need, actually feed the armed conflict. In August 2006, to tackle a likely onslaught by rebels, President Deby requested advance payments from Chevron and Petronas, which agreed to pay some US$300 million, which nevertheless did not exempt them from a unilateral revision of their operating contracts.

Caught up in this web of overlapping conflicts are some 200,000 refugees from Darfur and 150,000 Chadian displaced persons, housed in 10 camps all located some 60 km from the eastern border, plus another 200,000 displaced in the Central African Republic (CAR) who are seeking sanctuary from the plundering of local bandits and the constant attacks by insurgents against President Fran?ois Bozize. The insecurity of these people is at the centre of the humanitarian crisis which the international operations by the United Nations and EU are seeking to curtail. This is, broadly speaking, the security issue which the EU hopes to alleviate by launching a military operation (EUFOR Chad/CAR) to protect the police and humanitarian action spearheaded by the United Nations (MINURCAT). The EU’s global projection is making its debut in this African scenario where it does not normally have a presence or clear, hard–nosed power to impact decisively on the situation. If so far its influence was backed by its substantial financial aid (some €50 million in development aid and another €30 million in humanitarian aid in 2007, plus another €10 million in 2008 to support the MINURCAT and EUFOR Chad/CAR missions), from now on its €90 million per year can hold little weight with a government that is receiving €1.4 billion in fixed oil revenues. This being the case, the EU can facilitate a modification of the Electoral Law, but it cannot enforce it.

France has a greater influence, and the only European embassy in the region, and it supports Deby’s regime, although it does have periodical disagreements with him in regard to democratisation and –most notoriously and recently– the episode involving the NGO Zoë’s Ark and the attempt to sneak children from the region into Europe. French political support is not unconditional, but it does view any alternative to the current regime as worse, and this view is shared by the US, which sees the hand of Islamic extremists in any action taken by the Sudan. Its military presence is limited, although significant (1,500) compared with the local forces (some 5,000 regular soldiers and as many insurgents), and although it can lend intelligence and air support to the governments of Chad and the Central African Republic it is not strong enough and open enough to definitively tip the military balance in N’Djamena’s favour or to prevent a large–scale conflict.

The Underlying Conflict and International Missions

The insecurity on the border with the Sudan, where the Sudanese refugees fleeing the Darfur conflict are living in camps, or the power vacuum in Chad, are fundamentally policing and humanitarian issues requiring aid which can only be given with sufficient military backing. The blockading of international organisations heightens the guilty conscience generated by the situation in Darfur and exerts pressure on governments to do something about the human catastrophe rooted on the border between Chad and the Sudan and, by extension, the region of Darfur and the north–west of the Central African Republic. The United Nations considered that an international force of at least 20,000 troops would be required to stabilise the Darfur region and prevent both Chad and the Sudan from using it as the launching pad for their rebel groups to oppose each other. The Sudan, in particular, has always opposed the presence of an international force such as the one proposed. In June 2007, the French Foreign Minister, Bernard Kouchner, tried in vain to convince his Sudanese counterpart, Lam Akol, to participate in the meetings of the Contact Group in Paris to prepare the deployment of 12,000 soldiers on Sudanese territory to set up a humanitarian corridor and alleviate the situation in Darfur. He had more luck persuading President Deby to accept a force comprising French and European troops. The authorisation, conveyed to the Security Council by Secretary General Ban Ki–Moon in his report S/700/488 dated 10 August, reflected Chadian consent for the mission, but there was no consent from the Sudan, which continues to be suspicious of any military presence in the region.

Based on this preference, the UN Security Council began designing an international mission supported by three components: humanitarian, police and military. The United Nations would handle the first and Chad the second, with UN backing. The mission would be rolled out in the areas where refugees and displaced persons from eastern Chad and the north–eastern Central African Republic are located, but there would be no military presence on the border. In parallel, the EU began to prepare to take charge of the military component of the mission and its Council meeting of 23–24 July approved its involvement in the UN mission. The 12 September meeting approved the concept of crisis and the Secretary General and High Representative of CFSP reported five days later to the Secretary General of the United Nations that the EU was willing to take charge of the operation’s military component during the first 12 months.

UN Security Council Resolution 1778/2007, of 25 September 2007, authorised this multidimensional mission in the Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT). Its military component is authorised to act under Chapter VII of the Charter, which allows the use of force if necessary, even acting ‘with all necessary measures’, which in UN resolution terminology affords a considerable degree of discretion to whichever party it is empowering. According to the concept agreed for the mission, MINURCAT seeks to alleviate the humanitarian problem in the region, but does not act against its structural causes or its instigators. The efficiency of its therapeutic effect depends objectively on the police stabilisation and humanitarian assistance provided, but it also depends subjectively on how this is perceived by the parties involved. With so many different groups and such complex dynamics, it will be difficult for any humanitarian mission to be perceived as neutral and it runs the risk of becoming an additional focus of conflict. The duty to protect humanitarian forces in such a complex and volatile scenario will directly affect the balance of power or the struggle to alter it, and will impact indirectly if the parties believe that the mission undermines their interests. Control of the region occupied by refugees might help facilitate humanitarian action, but could also compromise it if any of the governments in the region perceive that the area is becoming a haven for rebels who act in their territory.

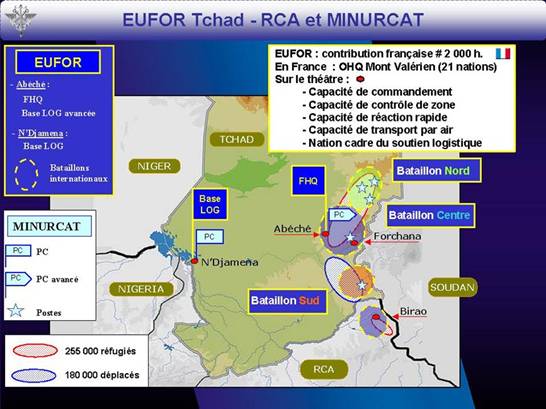

Against this backdrop, the EU began planning the operation in July 2007 to take charge of security in the refugee camps, a similar mission to that carried out in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Operation Artemis in 2003. Backed by UN Security Council Resolution 1787, approval of which would not have been possible without the backing of Europe and, in particular, France, the EU approved the subsequent joint action in EU 2007/677/PESC, dated 15 October, to launch the operation. The European component of MINURCAT, operation EUFOR Chad/CAR, comprises 14 nations and 3,700 troops (of whom 2,100 are French). The chain of command depends on the Irish general Patrick Nash, as commander of the operation, which is directed from the French operational headquarters of Mont Valérien, and with a ground force commander who is also French, namely general Jean–Philipe Ganascia. The mission is not designed to be permanent, and is limited to 12 months from its operational launch date, and subsequently the plan is to hand over to African forces, as in Operation Artemis.

Figure 2. EUFOR Chad–CAR and MINURCAT

Source: French General Military Defence Staff.

The Current Conflict, or How Local Reality is Overlooked by International Plans

While the operation was being launched there were continued clashes in the eastern border regions of Ouaddi and Wadi Fira, to the point where the Chadian government was forced to declare a state of emergency in mid–October. Libyan mediation managed to secure a compromise on 25 October between the Presidents of Chad, Idriss Deby, and the Sudan, Omar al–Bashir, and the leaders of the rebels belonging to the Movement for Resistance and Change, the National Accord of Chad and both factions of the UFDD. However, on 26 November 2007, the media announced that clashes had resumed between the Chadian forces and some rebel groups which had taken part in the October ceasefire. The clashes took place in the eastern cities of Farchana and Abeche and lasted for several days. Each side accused the other of having broken the ceasefire and said it was willing to reinstate it, but the situation continued to deteriorate. The fighting took place while the mission was being prepared and expert security analysts (Paul–Simon Handy, ISS, 5/XII/2007) already began to question whether the arrival of foreign troops might remedy or worsen the conflict, because the mission could potentially be caught up between the two sides or be associated with one or other side. Accordingly, for example, these analysts predicted that it would be difficult to distinguish the forces on the EU humanitarian mission from the UN peacekeeping force, and to distinguish the two chains of command acting in the same area. They also warned that, given France’s support for President Deby, the European mission ran the risk of being perceived as a covert prolongation of the military assistance which France provides to the N’Djamena regime via other means.

Like a self–fulfilling prophecy, sure enough, on 30 November, UFDD rebels declared ‘war’ on the foreign forces, a risk which President Sarkozy took on and which, in his opinion, justified the deployment of troops with the European mission. The Chadian government took the declaration as an attempt at bribery to prevent the European deployment and from then on pressured the EU not to delay the mission to stop the imminent rebel attacks leading to civil war. This time, forces from the UFDD, Mahamat Noure –former Defence Minister in the Deby government–, the Rally of Forces for Change (RFC) under Timane Erdimi –Deby’s former Chief of Staff–, and the UFDD spin–off led by Abdelwahid Aboud joined together. The group’s cohesion is based on its aversion to Deby; the first two leaders left his government and its militant groups include Gorane and Zaghawa, which makes it a truly inter–ethnic coalition. Furthermore, the clashes spread to the Central African border.

On 8 January, the Chadian Air Force attacked rebels operating between the camps of Goker and Wadi Radi, some 30 km inside the Sudan, crossing the porous border which ground–based actions cannot seal. While the EU was generating forces to do so, the fighting inside and outside these areas intensified. The tensions forced a summit, hosted by Libya in Tripoli, between Presidents Deby and al–Bashir, together with other regional leaders on 27 January, prior to the meeting of the African Union in February. The next day, the EU operation was launched and on 31 January the rebel forces advanced towards the town of Ati –450km from N’Djamena– and forces loyal to the government went out to meet them. The 5,000 members of the Republican Guard could not contain the aggressive attack using more than 300 vehicles and 1,500 insurgents with light weapons. Neither the helicopters nor the forces deployed could prevent the rebels from advancing towards N’Djamena and taking up positions some 200 km from the Chadian capital, after the clashes in Massakory (200 km) and Massaguet (60 km). In the end, the rebel troops entered the capital and attacked the government forces holed up in their nerve–centre inside the presidential palace to the south–east of the city. The deteriorating situation led the French government to send 150 troops from Gabon to reinforce the French forces in Chad as part of Operation Epervier and evacuation commenced, but they were not sent to enter directly into combat but to provide intelligence and advice to the Chadian forces. Both the concentration of residents and the airlift between N’Djamena and Libreville, and from there to European destinations, worked well, and in a few days 881 people of 27 nationalities were evacuated.

On the second day, as the fighting, pillaging, displacement of the population and personnel from governmental and non–governmental agencies stopped and started amid rumours of peace talks, the rebels opened another front in the town of Adre, near the conflictive Sudanese border with Darfur. Only the swift arrival of the rebel forces from the Justice and Equality Movement from the Sudanese border managed to shore up President Deby’s military position, but not so his political position, since he could no longer continue to allege that he had no links with groups acting against the Sudan.

At the emergency meeting of the UN Security Council on 3 December, the use of force for seizing power was condemned, reflecting that the nature of the conflict is that of an internal civil war and that it is qualitatively different from isolated hostile activities. The French Ambassador to the United Nations, Jean-Maurice Riport, sought to lend President Deby all the necessary support, but the Russian veto on including the expression ‘all necessary means’ in the final declaration made France’s request for more specific support for Deby’s government a vague appeal for non–interference in Chad according to the principles of the United Nations Charter. The rejection of the French proposal sidelined any debate as to who would be in charge of using all the necessary force: the EUFOR Chad/CAR, another UN force or France itself. The African Union summit went further and condemned the rebel attack, and its President, Tanzanian Jakaya Kikwetelleg, threatened to expel Chad if the government was overthrown by force. A statement along these lines might have been useful three days earlier, when regional leaders met in Libya to prepare the summit in Ethiopia on 31 January, but after the firm declaration the only action taken was to refer the problem to the mediation of Libya, which, by the way, has become a facilitator of consensus thanks to the regional conflict.

Conclusion

What Now? Lessons Learned?

Whatever the result of the actions underway, it will be far from a mere setback and the delay in the operation should be used to reflect on what has happened. Regarding Chad, events should be taken into account not so much because of the military result of the conflict but because of its political and strategic significance. On the day this analysis was completed, the rebels had withdrawn –defeated according to the Chadian government, and as a tactical measure according to the rebel leaders– from N’Djamena and less intense clashes continued in certain outlying areas. However, it is the second time the rebel forces risk trying to seize control of the capital. While in April 2006 the government easily fended off the UFDD rebel presence in the capital, this time it was not a single rebel group, but a coalition, which managed to actually enter the capital, force the evacuation of foreign residents and show sufficient determination to take up arms in order to resolve the power struggle. President Deby would do well to learn from this experience and warm to the idea of power sharing before he loses it entirely at the next attempt. As in the political struggle, the military fight is still a dead–heat and neither party is able to clearly defeat the other. This time around, the rebels are unlikely to be co–opted, as they were in 2006 when Mahamat Noure was offered the post of Defence Minister, and the rebel forces were offered integration into the Chadian Army payroll, to secure the ceasefire of October 2007. Neither does it appear that the weapons purchased with petrodollars have given Deby an operating advantage over the rebel forces which receive equipment from the Sudan, also purchased with oil revenues. Just as in the political struggle, neither side is in a position to claim a clear victory, and if Chadian forces were unable to keep rebel troops out of N’Djamena, neither did the rebels manage to occupy the capital and overthrow President Deby. However, if the monopoly on power is the cause of armed clashes, they will continue for as long as power is not shared, and it may be a case of ‘third time lucky’.

The United Nations and the EU should review the pivotal concepts of the operation because the weakness of the humanitarian effort against armed action has been demonstrated. If previously missions were not launched due to the existence of armed conflicts and the reluctance of regional leaders to accept an international presence, now the missions underway have proved to be as vulnerable as they were then. As well as the humanitarian risk, there is a risk of civil war inside Chad and a risk of cross–border war between Chad and the Sudan, albeit via opposing rebel groups. These conflicts interact and feed each other and humanitarian protection cannot be separated from the risk of war. As long as tensions between Chad and Sudan are not defused, Darfur will continue to be a breeding ground for rebellion and suffering. The situation has changed and the launch of a humanitarian operation in the wake of a local agreement was followed by a clash between the parties which alters the framework of the MINUSTAR and EUFOR Chad/CAR operations because it deprives them of the consent of the parties involved. Of course the operation will be supported by the Chadian government and the groups which oppose the Sudan –as long as they do not consider that the troops deployed are offering protection to their rivals– but it will be opposed by the rebel forces –who have already made a show of force to warn of their opposition– and the spectre of French support for the questioned Deby regime raises doubts about the EU’s partiality and places it in the sights of rebel destabilisation, whether supported by the Sudan or not. International missions are still indispensable and there have been attempts to take advantage of the opportunity, but that window of opportunity has closed and now is the time to take another look at how to open it without letting the UN troops get their fingers caught in the process.

The vulnerability might be reduced if there were stronger military forces, but the process of generating forces has again showed that the resources shape the will to help. Power and force have certain codes in that pre–modern Chadian security area that westerners and in particular Europeans should try to understand before rushing in with solutions that are miserly in terms of both time and resources. Twelve months of European mission is little time to stabilise the area, and the regional resources do not appear to be plentiful enough for a handover once that period has ended. As for the resources used, Europe’s difficulties in generating forces caused a delay in the initial deployment, which had been scheduled for November 2007, for the same old reasons: lack of sufficient critical resources such as helicopters and hospital equipment, which were not solved until an additional contribution by France on 11 January 2007 allowed an operational plan to be drafted.

The quality of available intelligence must also be reviewed. When the operation was being proposed, alarm bells sounded constantly regarding clashes and the rejection of rebel groups of a foreign presence. French intelligence should have predicted the rebels’ uprising to prevent stabilisation of the border from hampering their ability to cross it and jeopardising their havens. Furthermore, the mission’s planners should have known about the precedent in October 2006 when UFDD forces occupied the towns of Am Timan and Goz Beida, to the south east, and threatened to march on into N’Djamena. At that time the mobilisation of rebel forces loyal to President Deby and French support were enough to quell the movement, but it was a first attempt at using force to overthrow the current government, and the pattern has recurred. Preventing what happened seems to be a matter of common sense, and within the grasp of forces deployed on the ground and equipped with air surveillance resources. It is true that the reconnaissance mission headed by general Nash took place between 21 and 24 October, when the ceasefire was in force, but it is also true that the ceasefire fell apart two days later and that at the press conference on 29 January to unveil the operation general Nash admitted that there had been recent hostile activities. Nevertheless, the deployment of 70 troops sent in to prepare the launch of the operation went ahead. However, only two days later rebel forces took the Chadian –and European– forces by surprise by mobilising 2,000 insurgents and 300 vehicles, which progressed 1,000 kilometres under a unified leadership. As a result of this faulty intelligence, on 31 January the arrival of the first aircraft carrying special forces from Ireland to cover the EU deployment was aborted and another Austrian aircraft with equipment had to turn around and return to Tripoli. If there is a fault, the operation will need to be resumed once this fault has been ironed out, and not when the clashes cease, as seems to be the intention of those in charge.

The European EUFOR Chad/CAR mission has been suspended until calm is restored, but the EU can do little to restore it. Meanwhile, it should review its management concepts and the operating plan in place to remedy the planning errors made evident by the clashes in February 2008. However much the EU might wish otherwise, there is no such thing as a bargain mission (bonne, jolie et pas ch?re, as the French version affirms).

Félix Arteaga

Senior Analyst for Security and Defence, Elcano Royal Institute