Theme

This analysis unravels the key elements of the complex monetary and exchange-rate policy framework of Argentina’s stabilisation plan, as well as looking at its achievements and challenges.

Summary

The monetary and exchange rate policy of Argentina’s stabilisation plan, implemented under the government of Javier Milei, is a complex work of financial engineering. The framework combines an official exchange rate (with a preannounced monthly devaluation rate of 2%) with a floating exchange rate in the parallel market. It also incorporates traditional monetary policy tools such as interest rates and quantitative targets on monetary aggregates, alongside exchange controls (known as the cepo) and interventions in the parallel (blue) dollar exchange-rate market.

The plan has been implemented in three main phases: (a) an initial phase of severe monetary contraction (December 2023-April 2024), an increase in dollar purchases and in the central bank (BCRA) reserves, a flat blue exchange rate, and the narrowing of the gap with the official rate; (b) a phase of monetary easing (April-July 2024), spurring a nascent economic recovery, but also leading to a renewed widening of the exchange-rate gap between the parallel and official rates, while the BCRA’s dollar purchases dropped to negligible levels; and (c) a phase where monetary expansion came to a halt (July-October 2024), the exchange rate gap was nearly eliminated and international reserves were strengthened.

The plan’s achievements have been significant: aligning devaluation expectations with the BCRA’s policy of 2% monthly devaluation, virtually eliminating the exchange-rate gap, accumulating international reserves and sharply decelerating inflation to levels consistently below market expectations.

These advances, however, came at a cost: a sharp decline in incomes and an initial contraction in economic activity –an expected effect in stabilisation programs that start with severe monetary tightening– which led to a significant increase in poverty levels.

The challenge now is to dismantle capital controls and transition to a monetary and exchange rate regime that consolidates these achievements, advances the normalisation of the economy, and drives a robust recovery. The effectiveness of the hybrid monetary-exchange rate framework in anchoring market expectations and impacting key macroeconomic variables offers insights into the post-cepo monetary and exchange rate regime.

Analysis

There is room for debate about whether the fiscal adjustment under Milei’s administration was the result of the dilution of the real value of nominal commitments (a rise in nominal expenditure below the increase in the price level) or of the ‘chainsaw’ (a reduction in public expenditure). One could also debate whether the fiscal adjustment is sustainable over time or whether the interest on government debt is properly accounted for (given that the Letras del Tesoro Capitalizables, or LECAPs, capitalise their interest, it is not recorded in the fiscal balance). Everything is open to debate, and as usual, economists are doing so. However, the great advantage of fiscal accounts is their simplicity: expenditures – revenues = fiscal balance.

This is not the case with monetary policy. Even in a context without multiple exchange rates, without capital and exchange controls, without dollarisation or a de facto bi-monetary economy, and without a Central Bank that pays interest on its liabilities (or where these are borne by the Treasury, and the Central Bank ensures liquidity for the Treasury’s debt instruments), monetary policy remains one of the most complex areas of macroeconomics to understand, describe and analyse.

It is complex even in the absence of all these factors. Yet Argentina has them all. The analysis below aims to unravel the key elements of the monetary and exchange-rate policy of Milei’s stabilisation plan and to assess its impact on key macroeconomic and financial variables.

1. Nominal anchors

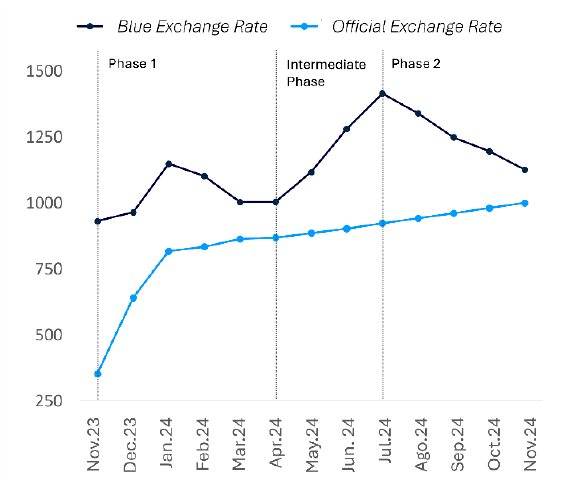

The nominal anchor of Argentina’s stabilisation plan is a hybrid scheme that combines elements of a fixed exchange rate regime and a floating rate regime, with a predetermined floor and, above that floor, a floating regime without an explicit ceiling (see Figure 1).

The official exchange rate is predetermined, with a preannounced monthly devaluation rate of 2% and exchange controls (commonly referred to as the cepo in Argentina). At the predetermined exchange rate, the Central Bank (BCRA) commits to buying all the dollars being offered, thereby establishing a floor for the parity between the official exchange rate and the dollar. By committing to purchase all dollars offered at the predetermined official rate, the BCRA is obligated to issue national currency to meet that demand if the market seeks pesos and sells dollars to the Central Bank to obtain them.

However, the BCRA does not commit to selling all the dollars demanded at the official exchange rate, as would typically be the case in a conventional fixed-exchange rate regime. This is because the BCRA lacks sufficient reserves to effectively maintain the official exchange rate parity without rationing dollar demand (for imports of goods and services, repatriation of dividends and other uses) or forcing exporters to sell dollar revenues to the BCRA at the official rate. In this way, exchange controls de facto play the role that international reserves would play in a conventional fixed exchange rate regime without such controls.

Figure 1. Hybrid exchange rate regime (average monthly exchange rate, Argentine pesos per dollar)

The exchange rate floats above the floor established by the official rate, without an explicit ceiling. As such, the parity with the dollar within the floating range is determined by the market and is referred to as the ‘blue dollar’ exchange rate.

The monetary control instruments in the floating range of the exchange rate available to the BCRA are as follows:

- Intervention in the parallel (or blue) exchange market: the BCRA can sell (or buy) dollars in this market to withdraw (or inject) pesos into the economy.

- Interest rate on BCRA liquidity control instruments (LeFi): the BCRA can raise (or lower) this rate to withdraw (or inject) pesos into the economy.

- Exchange controls: exchange controls aim to prevent accumulated (and, in principle, unwanted) stocks of national currency –mainly generated by unrepatriated dividends during the implementation of the cepo– from being suddenly converted at the official exchange rate to be transferred abroad.

These monetary regulation instruments in the floating range enable the BCRA to control liquidity in the economy (and even set a quantitative target for the Monetary Base).

2. Monetary policy: impact on macroeconomic and financial variables

Since the launch of the stabilisation plan, the BCRA’s monetary policy has gone through three distinct phases:

- Phase 1: marked by a severe contraction of the economy´s liquidity (December 2023-March 2024).

- Intermediate phase: characterised by monetary easing and liquidity expansion (April-July 2024).

- Phase 2: a sudden halt in the pace of monetary expansion (July-October 2024).

Below we analyse the impact of these monetary policy phases on a key group of macroeconomic variables: the blue exchange rate, the exchange rate gap, international reserves, inflation and economic activity.

3. Phase 1: devaluation, dilution and liquidity contraction (December 2023-April 2024)

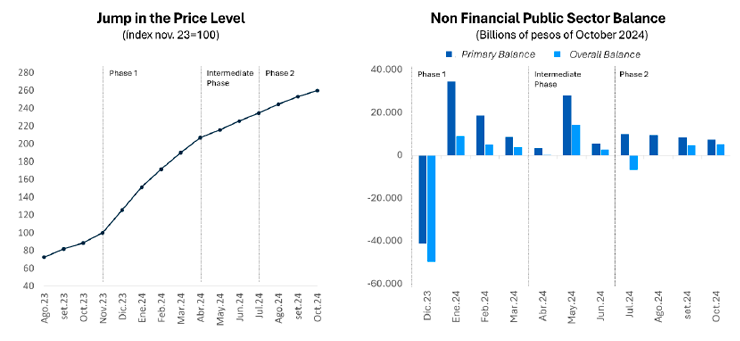

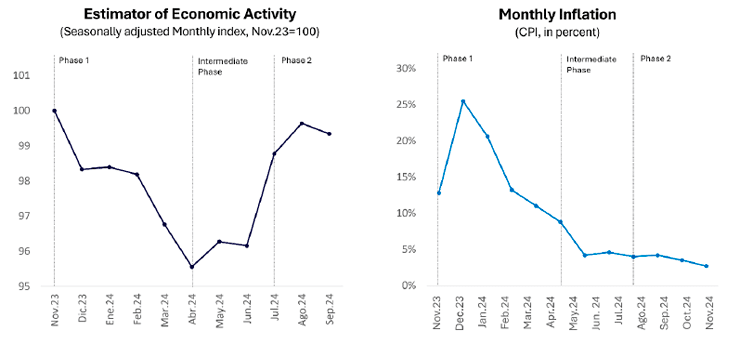

The stabilisation plan began in December 2023, just days after President Milei took office, with a 100% devaluation of the official exchange rate, a simultaneous adjustment of public utility rates and the liberalisation of controlled prices. These measures triggered a surge in the price level: the Consumer Price Index (CPI) doubled in just five months, between December 2023 and April 2024 (see Figure 2).

As shown in Figure 2, these price adjustments were accompanied by an extremely severe fiscal adjustment, partially facilitated by the dilution of the real value of primary expenditure resulting from the jump in the price level. As a result, the fiscal balance of the non-financial public sector shifted from an annual deficit of nearly 5% of GDP in 2023 (Milei took office on 10 December 2023) to a surplus by January 2024. The surplus has been maintained to date and is expected by the markets to persist through 2025.

Figure 2. Jump in the price level and fiscal adjustment

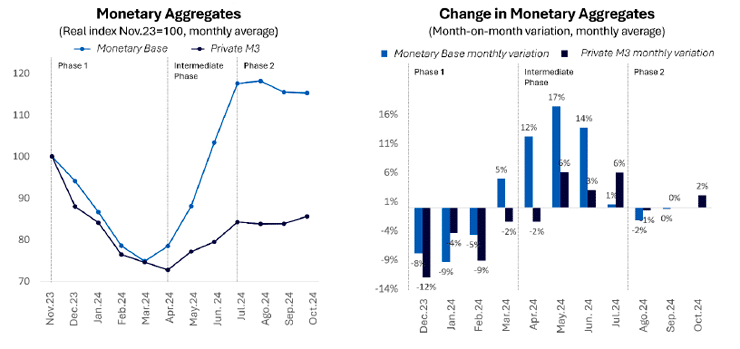

The surge in the price level also led to a sharp reduction in the liquidity of the economy. Between December 2023 and April 2024 the BCRA’s base money contracted by 35% in real terms, while secondary money (measured by M3) decreased by 27% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Liquidity of the economy

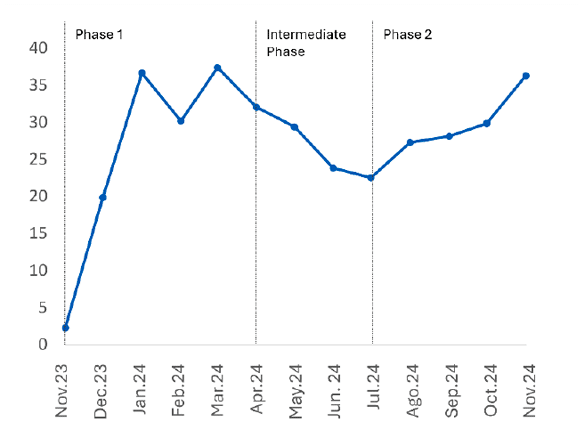

The contraction in liquidity triggered a dramatic increase in the opportunity cost of holding liquid money (which, in our view, is the conceptually correct measure of market liquidity).[1] The spread between the interest rate charged by banks on personal loans and the rate on the BCRA’s liquidity management instruments rose from an average of 2 percentage points (200 basis points) in November 2023 to an average of 30 percentage points (3,000 basis points) between December 2023 and April 2024.

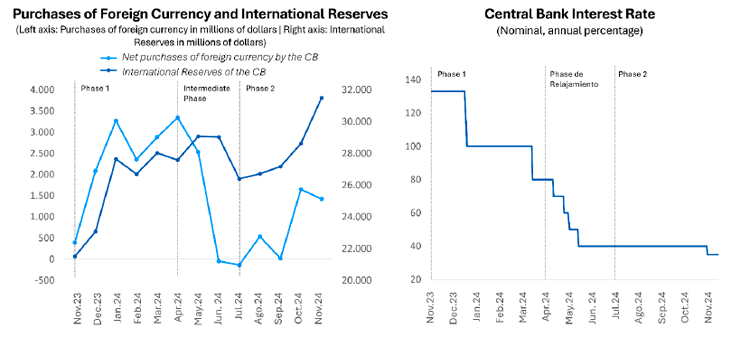

Figure 4. Opportunity cost of holding money (spread between personal loan rate and the BCRA’s interest rate, in %)

The severe contraction of peso-denominated liquidity not only led markets to sell dollars to the BCRA in exchange for pesos, resulting in a significant increase in international reserves during the first phase of the plan (gross reserves rose from US$22 billion in November 2023 to US$28 billion in April 2024, an increase of 28%), but also allowed the BCRA to reduce the interest rate it paid on its interest-bearing-liabilities at the time (from a 133% nominal annual rate to 80% between December 2023 and April 2024). The reduction was possible because the now-scarce liquidity of the Central Bank (of which its interest-bearing-liabilities are a part) became more valuable.

Figure 5. International reserves and BCRA interest rate

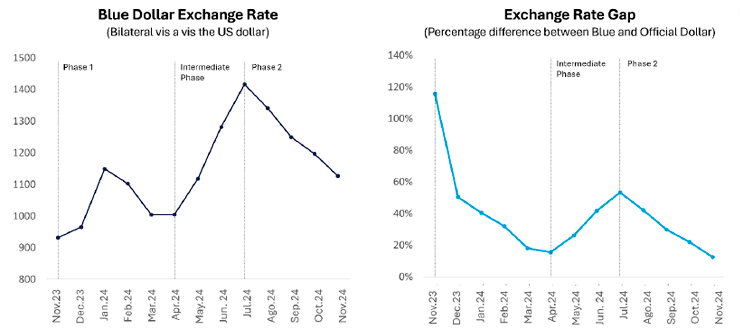

The severe illiquidity of the economy resulted in the stabilisation of the blue exchange rate and a sharp reduction in the exchange rate gap between the blue dollar and the official dollar, which decreased from an average of 120% in November 2023 to 20% in April 2024.

Figure 6. Blue exchange rate and exchange rate gap

Meanwhile, the contractionary fiscal and monetary policy triggered a sharp decline in economic activity and the inflation rate. The Monthly Economic Activity Indicator (EMAE), an index that anticipates quarterly GDP growth rates, dropped by 4% between November 2023 and April 2024. At the same time, inflation fell from 13% in November 2023 to 4.2% monthly in May 2024.

Figure 7. Macroeconomic outcomes

4. Intermediate phase: monetary easing (April-July 2024)

Between April and July 2024 there was a period of monetary easing and a significant liquidity expansion, as measured by base money and M3 (Figure 3).

This may have been driven by the rapid series of interest-rate cuts by the BCRA (from 80% nominal annual rate at the end of April to 40% by mid-May 2024) and the initiation of the replacement of BCRA interest-bearing-liabilities (pases) for LECAPs, as the cancellation of BCRA’s interest-bearing/-liabilities was not perfectly synchronised with the absorption of those pesos through the placement of LECAPs.

During this intermediate phase, the opportunity cost of holding liquid money fell by 10 percentage points (1,000 basis points). Monetary easing resulted in a sharp surge in the parallel dollar exchange rate (reaching 1,600 pesos per dollar in July) and the exchange rate gap (which rebounded to 60%), an abrupt drop to nearly zero in BCRA dollar purchases, a weakening of international reserves and an interruption in the inflation reduction process, which remained above 4% until July 2024.

On the other hand, this period of monetary easing coincided with the beginning of the recovery in economic activity (see Figures 4 to 7).

5. Phase 2: ‘closing the taps’

The government announced Phase 2 of its economic plan in late June and implemented it throughout July. In addition to reaffirming its commitment to fiscal balance and maintaining the 2% monthly devaluation of the official exchange rate as well as exchange controls, the goal of the phase’s policy measures was to tighten monetary policy by closing all remaining sources of monetary expansion:

- Elimination of BCRA interest-bearing-liabilities. These were swapped for LECAP and LeFi, transferring the responsibility for interest and principal payments to the National Treasury.

- Buyback of the stock of puts held by the financial system. These represented a ‘sword of Damocles’, a contingent claim on BCRA’s base money and a potential source of monetary expansion.[2]

- Sterilisation of peso issuance resulting from BCRA dollar purchases in the official exchange market. This was achieved through dollar sales in the Cash with Settlement market (Contador con Liquidación or CCL in Spanish), which has a similar rate to the blue dollar.[3]

The combination of a fiscal surplus, the shutting down of all other sources of monetary expansion by the BCRA and a high monetary policy interest rate (40% at the start of Phase 2, later reduced to 35%, and most recently to 32%) relative to the 2% monthly devaluation rate created an extremely attractive dollar yield on peso-denominated instruments (for instance, a 35% nominal annual interest rate combined with a 2% monthly devaluation of the official exchange rate guarantees an annual dollar yield of 12%). This set of measures completely halted the growth liquidity, whether measured by base money or M3 (see Figure 3).

The consequences of halting liquidity growth were immediate: the opportunity cost of holding liquid money rose by almost 15 percentage points (1,500 basis points) between July and October 2024, the BCRA resumed dollar purchases in the official market and increased its international reserves (which now exceed US$30 billion), the blue exchange rate dropped significantly, reducing the gap with the official rate to nearly zero, inflation fell below 4% monthly in September and below 3% monthly in October, and the pace of economic expansion slowed despite the growth in bank credit to the private sector.

While acknowledging the influence of other factors (expectations of a new agreement with the IMF, trends in international markets, etc), this brief monetary-exchange rate history of Argentina’s stabilisation plan suggests that, supported by a fiscal surplus, the monetary and exchange rate policy has been effective both in anchoring expectations and influencing key macroeconomic variables.

Conclusions

The monetary and exchange rate policy of Argentina’s stabilisation plan is a complex work of financial engineering that combines a predetermined official exchange rate with a floating exchange rate in the parallel, or blue, market. It integrates traditional monetary tools, such as the BCRA’s interest rate and quantitative monetary targets, with exchange rate controls.

This framework, supported by a fiscal surplus and a cleanup of the BCRA’s balance sheet and the elimination of the quasi-fiscal deficit, has achieved key objectives: aligning devaluation expectations with BCRA’s announcements, reducing the exchange-rate gap between the parallel and official exchange rates to nearly zero, the accumulation of international reserves and a drastic reduction in inflation –consistently outperforming market projections–.

However, these achievements have come at a cost: a significant reduction in incomes and an initial contraction in economic activity (typical of stabilisation programmes that begin with severe monetary tightening), which has led to an increase in poverty levels.

The challenge now is to dismantle exchange controls and transition to a monetary and exchange-rate regime that consolidates the gains achieved, advances the normalisation of the economy and drives a robust economic recovery. The effectiveness of the hybrid monetary and exchange rate framework of the stabilisation plan, both in anchoring market expectations and influencing key macroeconomic variables, provides valuable insights into the post-cepo monetary and exchange rate regime.

[1] The authors thank Pablo Ottonello for having pointed this to them.

[2] The holder of a put has the right to sell (although not the obligation) Treasury Bills and Notes to the BCRA at a given price and for a predetermined period if their value falls below the price established in the put contract. To have an idea of magnitudes prior to the voluntary exchange operation, if all banks simultaneously exercised their right (something they can do at any time within the period established in the put contract) the BCRA would have had to issue the equivalent of an entire monetary base.

[3] The BCRA can handle this form of sterilisation at its discretion.