Original version in Spanish: El voto del enojo: el nuevo (o no tan nuevo) fenómeno electoral latinoamericano

Theme

Latin America’s intense electoral season has reflected its broad heterogeneity; nevertheless, the recent elections have also revealed the emergence of a cross-cutting phenomenon –the ‘anger vote’– common to the entire region.

Summary

This paper analyses the social, economic, institutional and political cultures that have given rise to the ‘anger vote’, an emerging phenomenon particularly visible in the region’s current election cycle (2017-19). The ‘anger vote’ can be defined as the rejection of political parties, traditional political elites and the record of democratic institutions by the majority of a country’s citizens. It also considers the diverse and heterogeneous features that such voting reveals and the types of leadership it promotes, along with some of the main examples of the ‘anger vote’ recently seen in the region. To conclude, it confirms the phenomenon’s existence, regardless of national variations.

Analysis

Introduction

Latin America is now in the midst of an intense election marathon. From October 2017 to the end of 2019, 14 of the region’s 18 countries will have elected (or in some cases re-elected) their Presidents. The election season is politically reconfiguring the region, challenging its balances and putting to the test the so-called ‘turn to the right’. The elections have demonstrated the region’s wide diversity: the victories of the centre-right have coexisted alongside the successes of social-democratic leaders (like Carlos Alvarado in Costa Rica), even more left-leaning figures (like Andrés Manuel López Obrador, AMLO, in Mexico) and even ‘21st century socialism’ (Nicolas Maduro, after a highly questioned election in Venezuela).

Despite the diversity, most of Latin America’s recent elections have something in common. More as a vote ‘against’ than ‘in favour of’, a significant portion of the region’s angry population has voted to punish the ‘establishment’, including the political elites and institutions. There is a general sense of dissatisfaction with the weak inclusiveness of public policies. Citizens also criticise the functioning of the political system and the working of the institutions, seeing them as ineffective mediators between citizens and a State that has become incapable of guaranteeing rights and basic procedures. In this context, many leaders –facing varying situations and distinct national dynamics– have been able to take advantage of discontent to win elections (AMLO in Mexico) or to move from the margins of the political arena onto centre-stage (the Frente Amplio in Chile and Fabricio Alvarado in Costa Rica).

As explained elsewhere, ‘in general, social fatigue with the democratic political system and its central institutions (the political parties, parliament, the judiciary and government administrations) tends to manifest itself as a vote against the system. With their corresponding national differences, corruption and violence have become the wrecking balls that punish the region and its people. In the recent past it was common to find a certain tolerance for corruption. National variations on the expression, ‘they steal, but at least they get things done’, have manifested themselves over time here and there. But the Odebrecht case –with its high-level political, economic and financial implications– has been a watershed. The patience of the citizenry has reached its limit. And although it is not expressed with the same resounding explicitness as when the Argentines, in the wake of the corralito, demanded that “they all should leave”, the lack of confidence in the region’s political leaders is now near complete’.

The political backdrop to the ‘anger vote’

Twenty years ago, as an expression of a desire extending across the region’s societies, Latin America experienced the emergence of a ‘vote of rage’ that condensed itself into the demand that ‘they all should leave!’ (that is, all the politicians of the moment). During the crisis of the ‘Lost Five Years’ (1997-2002), popular discontent did away with numerous governments. Elections in Mexico in 2000 ended 70 years of PRI domination. In 1999, elections in Venezuela brought an end to 40 years of bipartisan (adeco and copeyano) hegemony. Something similar happened in Uruguay in 2000 when the dominance of the colorados and the blancos came to an end. Meanwhile, ‘street coups’ and social explosions toppled governments in Peru (2000), Ecuador (2000 and 2005), Argentina (2001) and Bolivia (2003).

The end of the economic crisis (2002-04) and the boom of the Golden Decade (2003-13) opened a new chapter in the history of the region, driven by the rise in commodities prices and marked by the emergence of new leadership (including many from the so-called ‘turn to the left’). Political stability, enduring party hegemonies and the rise of charismatic leaders of varied ideology –including Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales, Daniel Ortega, Rafael Correa, Lula da Silva, Alvaro Uribe and the Kirchners– were characteristic of the period.

A decade later, such ways of conducting politics began to lose ground. In part, this was a result of the economic slowdown (beginning in 2013) and a growing fatigue among voters with both old and new leaders. Popular unrest re-emerged to form the backdrop to the coalescing ‘anger vote’ which had a treble origin: a rejection of the existing political and institutional frameworks (clientelism, corruption and bad administrative practices); a questioning of the economic model (given the crisis and the slowdown); and ongoing social discontent (reflected in a fall in expectations for intergenerational improvements and a fear of losing achieved status, especially among the heterogeneous middle classes).

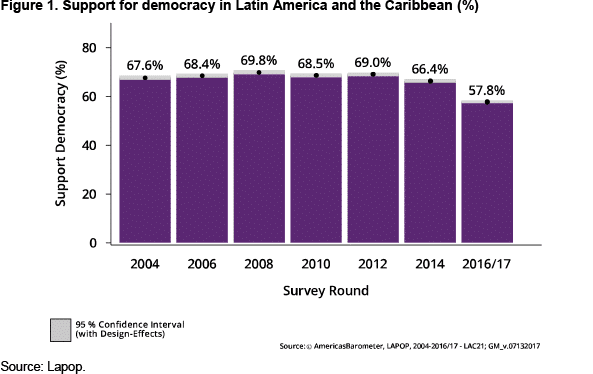

Various opinion surveys confirm this. For the past six years, Latinobarómetro has reflected the growing disaffection in Latin American societies with democracy, the political class and republican institutions. However, the problem is not unique to the region: it also plagues the EU and the US. Furthermore, such sentiment has grown in the wake of the expansion of the region’s middle classes and their growing citizen demands –now perceived to be increasingly ignored–. The Latin America Public Opinion Project (Lapop) reveals a decline in public support for democracy of 12 percentage points in only five years: from 69% in 2012 to 57.8% in 2017.

Democracy itself has seen an in its effectiveness, as have the leaders in charge. The change in the economic cycle made clear the bankruptcy of the official classes, whose governments had fewer and fewer resources as exports fell. Some elites were defeated at the polls because their middle-class societies demanded better-functioning public services and they made their discontent felt in their votes.

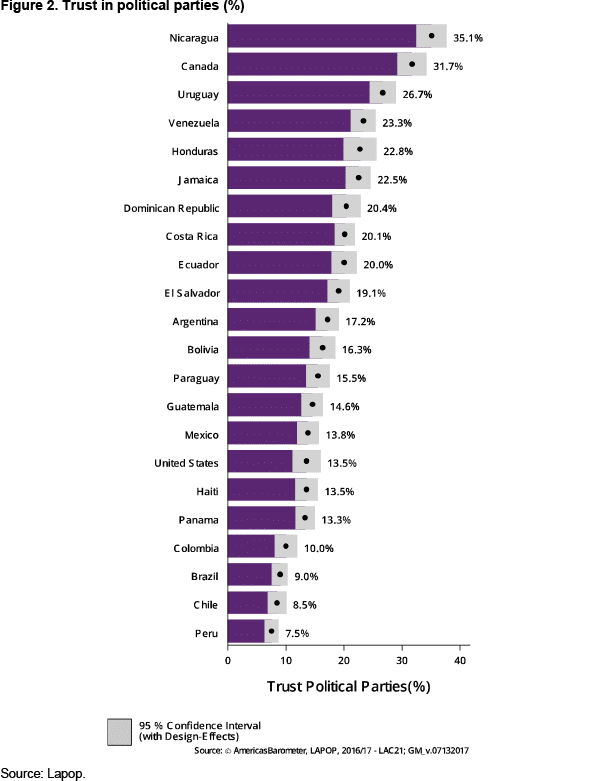

The region’s public has indicted their public institutions and political parties: indeed, many of them no longer believe in democracy. What is more, according to a Lapop survey in 2017, support for democracy is even weaker if considering the public’s opinion of related democratic institutions, like political parties. Across the region as a whole, the highest level of public confidence in national political parties (only 35%) is found in Nicaragua (see Figure 2).

The widespread inefficacy and inefficiencies of Latin American public administrations in the provision of adequate public services has mobilised the middle classes and eroded presidential popularity. Over the course of the past decade the process has taken root across the region. In 2011 the Chilean middle classes took to the streets to demand better public education. In 2013 and 2014 the same classes swarmed the streets of Brazil seeking improvements in transport and other public services. And in 2015 corruption prompted the Guatemalan middle classes into taking action, leading to the fall of Otto Pérez Molina. All these cases had much in common: in a context of anaemic economic growth, the state maintained neither adequate citizen security nor sufficient public services (health, education and transport), showing signs instead of widespread corruption. This caused intense social protest led by the middle classes.

During the commodities boom, the middle classes grew and poverty declined. From 2003 to 2013, between 70 and 95 million people rose in socioeconomic terms. But this is a highly diverse social segment: its lower fringe is exposed to the vulnerability of dropping back to its previous social stratum given the lack of adequate social coverage or of any protective cushion. The middle segment fears losing its current status and previously acquired purchasing power. Slow economic growth (between 1% and 2% of the average regional GDP) is insufficient to attend to rising expectations and therefore threatens previously consolidated social gains. Nor do current growth rates suffice to reduce poverty or to generate enough quality jobs. On the contrary, anaemic growth now combines with rising inequality.

Characteristics of the ‘anger vote’

The rejection vote has been in the making for years now (at least since the end of the boom in 2013), undermining traditional political systems and parties, and challenging the historical political class. Rejection is aimed at ineffective public administrations and demands a strategy for the improvement of public services. Discontent has deep historical roots but has become more acute over the past five years. Its precedents go back to the beginning of the transition in the 1980s. From 2015, however, and especially today in 2018, its principal manifestation has become the ‘anger vote’. And if it is true that the electoral trend is now spreading across many Latin American countries, the phenomenon’s characteristics are quite diverse, particularly given the region’s heterogeneity and the various political and electoral processes underway.

The ‘anger vote’ is a cathartic act which responds to the deep and widespread unrest and discontent with national institutions and representatives. The electorate seeks alternatives to the traditional parties and leaderships and tends to support figures who present themselves as ‘outsiders’, although they rarely really are. The major exception in this regard is the Guatemalan Jimmy Morales, an actor who plunged into politics as a stranger to the traditional political classes. Others in the group have held positions of responsibility as governors or mayors (AMLO and Petro), as ministers (Juan Diego Castro) or as parliamentary deputies (Jair Bolsonaro and Fabricio Alvarado). Others have had a place within the parliamentary opposition (the Chilean ‘Broad Front’) but without wielding any power or responsibilities at the national level.

After occupying posts below the national or ministerial levels, these leaders have become the opposition. They are not sustained by the large parties but rather draw on support from the political margins. For instance, Bolsonaro is the candidate of the tiny Social Liberal Party, while Fabricio Alvarado was the candidate of the National Restoration Party (which until 2018 had no more than a single deputy in the national parliament). Others have always been in the opposition (like MORENA, in the case of AMLO, despite his early passage through the PRI) and have integrated recently into newly created coalitions (the ‘Broad Front’ in Chile) or have contested elections backed by platforms without links to the traditional parties (as in the case of Gustavo Petro).

These leaders do not seek a reform of the political system but rather to transmit a message of total rupture. They want to sweep away the current system (Juan Diego Castro), push for its refoundation (AMLO) or do away with certain ways of conducting politics (Petro and the so-called ‘marmalade’). This emerging electorate is linked to the formation of what specialists have called the new ‘cleavages’ (Kirchnerism versus anti-Kirchnerism, Uribe-ism versus anti-Uribe-ism, Chavismo versus anti-Chavismo and PRI-ism versus anti-PRI-ism) which are characterised by intense political –as opposed to ideological– polarisation. The phenomenon co-exists with the progressive fragmentation of the political spectrum and the party system, and alongside forces located within the ‘anti’ versus ‘pro’ dynamic. And if AMLO and Petro veered towards pragmatism and moderation during their campaigns, both back re-foundational projects. AMLO has reiterated that he will undertake the fourth transformation of Mexico –following Independence, the Reform and the Revolution– and that he wants to go down in Mexican history like Juarez, Madero and Lázaro Cardenas.

The ‘anger vote’ is neither linear nor monolithic; rather it is diverse and heterogenous. Nor is it highly defined, given those who embody it and express its meaning. It is more a vote ‘against something’ than a vote ‘in favour of somebody’ –more a vote ‘against the system’ than an ‘anti-system’ vote. For this reason, it is carried forward by strong leaders, although they are often of different political tendencies. They range from Bolsonaro on the extreme right to Petro and the Chilean ‘Broad Front’ on the left; they include the nationalist demands of AMLO and Fabricio Alvarado’s mobilisation of the ultraconservative evangelical vote in defence of traditional values. Beyond the nuances that separate Bolsonaro (with his authoritarian, sexist, xenophobic, racist and homophobic messages) from Petro (equal rights for women and homosexuals), they share an anti-establishment and anti-party idiosyncrasy which is fed by the frustrated middle classes in the face of governments overwhelmed by popular disaffection and unrest, given their subpar administrative management and the lack of adequate public policies.

The leaders and movements riding upon this popular anger do not exercise any particular political pedagogy on their electorates. They merely feed the sense of exhaustion and disaffection. They have undoubtedly stoked a ‘revolution of rising expectations’, promising profound and rapid change while simplifying the content of their discourse. To capture the majority of the votes, their proposed solutions are direct, simple and not over elaborate. AMLO is a good example: regardless of his turn towards moderation during the campaign, the message that took hold among the people exhibited such characteristics. The simplicity of AMLO’s message transmitted the idea that only one factor was responsible for poverty, inequality, corruption and anaemic economic growth, summed up by the term the ‘mafia of power’: ‘No, things will not be allowed to continue. We will not play old-school politics according to the traditional political model. This brand of politics was shattered on 1 July. People no longer will tolerate corrupt, lying and high-handed politicians who are nothing more than false puppets’.

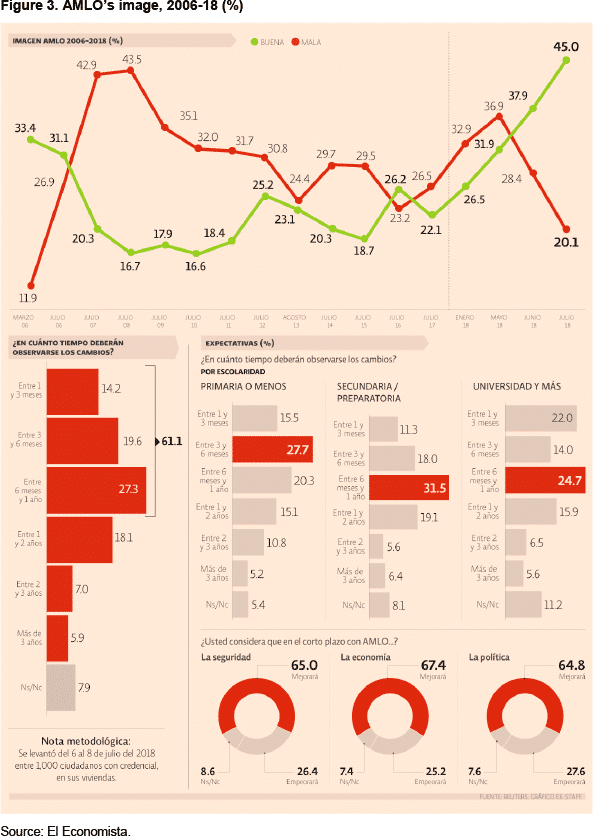

In AMLO’s message there is a rapid and simple solution to the structural problems of Mexico: the end of corruption, the origin of all problems. With AMLO’s election victory, Mexican society now has heightened expectations that the new government will enact policies in the short-run to improve the country’s economy and security. According to an opinion survey (‘Mexico after the elections’) by Mitofsky Consultancy, nearly seven out of every 10 Mexicans (67.4%) believe that with AMLO the economy will improve in the short term. Some 65% said that that he would improve security, while 64.8% believed that he would also improve politics in general. More than three-fifths (61.1%) think that the changes initiated by the new government will begin to make themselves felt during its first year.

The ‘anger vote’ has emerged in societies marked by the growing lack of both interpersonal trust and trust in public institutions. This gives rise to scepticism, high and demanding standards, and –ultimately– the creation of hypercritical individuals, unleashing a cycle of ‘distrust-scepticism-demand-criticism’, as Antoni Gutierrez-Rubi has argued.

Latin America is the most mistrustful region in the world. Eight of every 10 Latin Americans do not trust each other –in stark contrast to the Nordic countries, where 80% of citizens do trust each other–. However, Latin Americans trust their institutions even less. Trust in political parties is at the very bottom of the list: only 15% of Latin Americans trust their country’s political parties. This intense mistrust generates a society of sceptics, with political and institutional consequences. Support for democracy, according to Latinobarómetro, ‘has fallen from 61% in 2010 to 53% in 2017, while one in every four Latin Americans (25%) is indifferent to the form of their political regime’.

This mistrust and scepticism give rise to more demanding societies with respect to the functioning of a system that does not meet their expectations for the deepening of democracy. Latin Americans, especially the middle classes, are now more demanding in general. What was once acceptable at the turn of the century (corruption, inequality, violence etc.) is now no longer tolerated, since the traditional clientelism has become incapable of satisfying social expectations. ‘Dissatisfied democrats’ have emerged in diverse social sectors. These are citizens who support democracy but who are not satisfied with its functioning. Such higher demands lead to a more critical society: 73% believe that democracy is governed for the benefit only of a few powerful groups.

These new middle-class social players make new demands (citizen security, transparency, an efficient state, adequate public services and a solid economic expansion) that have not been channelled by a political class still essentially traditional (party-dominated and clientelist) in cultural and political terms. In such a climate of distrust and dissatisfaction, new players appear and prosper, offering alternatives to the parties and their historic leaderships.

These new actors are now capable of winning elections at the national level, or of influencing their outcome. Some of them are outsiders, emerging from beyond the traditional political system, wielding anti-party styles and discourses. They participate in elections without the support of a strong national party, and they have developed their careers beyond the traditional political channels. Their irruption on the scene modifies the structures of clientelist, territorial and historical power, bringing out business magnates and technocrats (Duque), evangelical pastors (Fabricio Alvarado), athletes and showbusiness personalities (Morales) as candidates.

Examples of the ‘anger vote’ in Latin America

During the current electoral cycle, emerging discontent has made itself felt in the ‘anger vote’. It emerged in 2017 in Chile and Honduras, and in 2018 in Costa Rica, Paraguay, Colombia and Mexico, and it is now rearing its head as a possibility in the upcoming Brazilian elections in October. In Chile, the ‘anger vote’ favoured the rise of the leftist ‘Broad Front’ (Frente Amplio) which captured 20% of the vote in the first round of the presidential elections, taking advantage of discontent with the Concertación government since 1990. Not only did it reject the government of Michelle Bachelet (2014-18) and that of Sebastian Piñera (2010-14), it also aimed its critical attack at the Post-Pinochet transition and the path of reform and continuity taken by Concertación since the dictatorship. Beatriz Sánchez, the ‘Broad Front’ candidate, accuses the Socialists and the Christian Democrats of being very unambitious and overly prudent in dealing with the country’s military legacy.

Where did the Chilean ‘anger vote’ come from? It was represented in previous elections by Marco Enriquez-Ominami (2009) and Franco Parisi (2013), and it grew in parallel with the slow and unequal economic growth rate, the corruption scandals, the deficiencies in public services and the growing disconnection between the party system and the electorate. The disaffection towards the political parties continued to grow, along with discontent over the political system and the public administrations and spread to many layers of society. The former President Ricardo Lagos reflected on this phenomenon in an interview with La Tercera. The long quote below sums up the political and ‘sentimental’ moment that Chile and Chileans are currently experiencing:

‘We are facing a grave institutional… crisis. This is not because the institutions no longer function… But they are losing their legitimacy. And this can be seen in the reaction of the citizens to the institutions of the Presidency, the Parliament, the Judiciary… We are not referring to the political parties. I think this is the worst (crisis) that Chile has ever experienced, at least in my memory. Although I leave aside the collapse of our democracy in 1973, when the country split in half. I am speaking exclusively in terms of legitimacy… What we have here is a crisis of legitimacy linked to a crisis of confidence. The citizens no longer trust the institutions or the political actors. We are all being questioned: all of us, whoever occupies positions of high responsibility. While collusion has dragged down the private sector, it is difficult not to speak of the capture of the state apparatus when the distribution of pensions is arranged in a back-handed way. The Church, which had formed part of the moral reserve of the country, has been severely damaged by its scandals involved the abuse of the minors under its charge. Who can be trusted? Where should we begin to rebuild? You will all certainly realise that to fight collusion, corruption, abuses and the privileged castes, we can no longer use a left-wing or a right-wing agenda. Rather we must respond to the need to convoke a great national encounter among all of us –yes, everyone– to regain mutual trust.’

Such words make clear that since the turn of the century the social, political, economic and even cultural environment in Latin America is increasingly influenced by a citizenry that is increasingly vocal and clear in its message that it does not feel represented in public decisions or policies, and that it feels further and further removed from the government and traditional political leaders. The gap between them and the different elites has only widened to the point of creating two parallel worlds with their backs to each other and with very few points of contact. The frustration with the last government stemmed from a failure to meet very high public expectations in the wake of Bachelet’s electoral victory. With respect to political institutions and the public administration, there has been a loss of confidence and a growing recognition of the very poor implementation of policies, inefficiency and poor management, along with a lack of transparency and corruption.

Although in a different way from Chile, Honduras also experienced a rise in the ‘anger vote’ in 2017. It took the form of a reaction to the decadent bipartisan model. The ‘anger vote’ also criticised the status quo, which from 2013 was incarnated by the predominant National Party, led by President Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH). Discontent was channelled by the ‘Opposition Alliance against the Dictatorship’, an unnatural coalition between the Liberty and Refoundation Party of former President Manuel Zelaya and the Anti-Corruption Party of Salvador Nasralla, which is opposed to the re-election project of JOH. Polarisation (zelayismo versus antizelayismo, and between backers and detractors of Hernández) began to take root in 2009 and then became entrenched between 2013 and 2017. Some of the slogans bandied about in the campaign were very revealing: Zelaya, the coordinator of the Alliance, demanded openly to ‘remove the Devil’ from the presidency. For his part, JOH appealed to the fear vote, warning the electorate that an opposition victory would lead not only to government misrule but also to the end of his social policies. His party published a press release challenging rival candidates Nasralla and Luis Zelaya to stop ‘spreading hate’.

After a vote count lasting for weeks, and overshadowed by suspicions, irregularities, tensions and disturbances, the Electoral Supreme Court declared Hernández the winner by a narrow margin: 42.95% to 41.2%. The process wounded Honduran institutions, given the government’s co-optation of the electoral institutions and Nasralla’s accusations of fraud: ‘It is clear that there was fraud committed before, during and after the elections… The President… is an imposter, and the people… know it’. All of this weakened Honduran society, democracy and its party system.

In 2018 fresh examples of the ‘anger vote’ emerged in Costa Rica, Colombia, Paraguay and Mexico (leaving to one side, for now, Venezuela). The elections of 2018 in Costa Rica (like those in 2014) implied a break from political and electoral history, ending an era that had begun in the 1990s and undermining the bipartisan domination of the National Liberation Party (NLP) and the Social Christian Unity Party (USCP). In 2014, for the first time since 1953, an unrelated party (Citizen’s Action Party, CAP) reached the presidency by defeating the NLP, the pre-eminent political force in the country since the 1950s (but especially since 2006).

The victory of Luis Guillermo Solís (CAP) in 2014 responded to a desire for change and social fatigue with traditional alternatives. Solís was the candidate of an emerging party, established in 2002 out of a division within the NLP. He had the image of a new leader, closer to the citizens and well-prepared (as a university professor). He promised a profound change at a moderate pace (an advantage compared with the radical break proposed by the leftist ‘Broad Front’). Solís was a different kind of candidate and he channelled the vote of discontent by prompting higher expectations.

The elections of 2018 were overshadowed by the issue of corruption. In Costa Rica the phenomenon took on the name of the cementazo and hammered Solís’s party, but also other traditional powers and institutions. Corruption infected the previous administrations (NLP and USCP) as well as the CAP, weakening the party system, the executive and the judicial and legislative powers.

During the last Costa Rican election campaign, the electorate sought a candidate that expressed a rejection of the parties, the institutions and the political class. Juan Diego Castro initially led the polls with his anti-party message. ‘He dreams of direct democracy, without parties or corrupt politicians’, was a phrase that appeared in the personal biography on his website in 2016. By the end of 2017 he led the polls, but then in January he slid out of the contest and the evangelical, Fabricio Alvarado, finally emerged. For Alvarado, ‘politics is not for the Devil. I believe that there are people possessed by the Devil that have entered politics. This I believe and unfortunately we have often voted for such people and we have placed them in the position to govern’. A protestant pastor summed up why Fabricio Alvarado and his ultraconservative message based on traditional values had such success, passing on to the second round to receive nearly 40% of the vote: ‘I believe the Church has awoken; the people are also waking up and telling the traditional politicians that no longer can it be more of the same because we want a change’.

The anger was first channelled by Castro, but then later by Alvarado, as Jorge Vargas Cullel points out:

‘… the available data point to the fact that in our country the majority of the people support democracy as the best system of government and they still believe in the promise that, without an army, the country has the capacity to raise the population’s level of well-being. People are increasingly angry with the system. Analysts inform us that the poor performance of governments and institutions end up, with time, undermining the foundations of democracy… The citizens are tired with the fact that democracies seem to generate increasingly unequal societies. Many believe that the same people always win the lottery while the majority always loses.’

Colombia is another particular case. The elections of 2018 yielded a protest vote aimed at the official sector –in power since 2010 and embodied by Santos–. It came both from the right (Uribe’s supporters) and from the left (Petro and his backers). The two candidates that criticised the government of Juan Manuel Santos –by going too far (Uribe’s block thought that Santos conceded too much to the FARC) and by not going far enough (for Petro, the Santos government had been too timid with structural reforms of a social nature)– passed on to the second round. Both Uribe’s movement, led by Duque, and the left, under Petro, sought the votes rejecting the President’s record and the disenchantment with a system plagued by high levels of corruption and clientelism (including the infamous ‘marmalade’ case in which political support was traded for access to financing). Despite his achievements in the peace process with the FARC, Santos had very high disapproval ratings (nearly 80%).

To vote for Duque or for Petro implied two ways of punishing the official caste and the parties. The Uribe front lined up behind the former President himself, but under the auspices of a party created in 2012 (the Democratic Centre). Petro, a hero in the fight against corruption and the ‘marmalade’, was not the candidate of a party but rather of the Progressive movement. Both represented something new –a renovation of the older and traditional frameworks– although with subtle differences. Petro has been in politics since the 1990s and served both as Bogota’s Mayor and as a Senator; Duque is a young man and a technocrat with a short political career as a legislator. However, Duque’s professional ‘godfather’ is Uribe, the strong man of Colombian politics since 2002.

In all of Latin America, AMLO has been the leader who has most fully expressed the sentiments of this ‘anger vote’. He brings together all of the characteristics of the disaffected electorate. He is a charismatic leader with a long political track record and he is backed by a peripheral party of recent creation with an anti-elite and anti-party discourse. He emerged within a context of disaffection and rejection of the current political classes, and of discontent with the inefficacy of the public policies of inefficient state apparatuses.

AMLO has channelled the anger of voters and established a special relationship with the young, despite his age (62) and the fact that he has been in politics since the 1980s. During the latest campaign he toned down some of his more polemical positions, holding in check his demagogic and populist tendencies. As Agustin Basave has pointed out:

‘… elections usually are won more on sentiments than on ideas. What happened… on the first of July occurred because society feels bad; it is enraged by inequality, insecurity and above all corruption. All of this is incarnated in Enrique Peña Nieto, whose disapproval rating now approaches 80%. And it has been Andrés Manuel López Obrador who has capitalised on practically all of this social indignation.’

Without going into many of the details of his programme, or how to implement it, AMLO centred his discourse on a rejection of the political class (the ‘mafia of power’) and the fight against corruption. His simple and direct proposal was to bring down corrupt politicians, which would allow the resolution of the country’s problems. Like Duque, he was not supported by a traditional party (unlike 2006 and 2012 when he was a candidate of the PRD), but rather by a recently created one, forged in his own image: MORENA. The growing feeling of overall social malaise and citizen fatigue with the traditional parties and elites that has come with the ‘revolution of expectations’ created by AMLO carried him to an overwhelming victory. With more than 50% of the votes, he doubled the vote count of his closest rival.

The ‘anger vote’ has many precedents since the return of democracy to the region: Alberto Fujimori (Peru 1989), Fernando Collor de Melo (Brazil 1989), Abdala Bucaram (Ecuador 1996) and, more recently, Chavez, Evo Morales and Correa (between 1998 and 2005), and then Jimmy Morales (Guatemala 2015). The next example of the ‘anger vote’ could manifest itself in Brazil, where the polls have Bolsonaro leading –excluding Lula da Silva– with around 20% of the intended vote. He is a figure who incorporates certain constant features of the ‘anger vote’: a politician of the system –not an outsider– and parliamentary deputy since 1990, Bolsonaro has never been in power and he aspires to an electoral victory with the support of a small party (the Social Liberal Party) and a Manichean and demagogic discourse that feeds on citizen discontent, particularly among the middle classes, with corruption and the breakdown of security, transport, healthcare and education. His discourse is of the ‘radical right’ (perhaps even extreme right, given his attacks on homosexuals and blacks, and his homophobic and male-chauvinistic messages), and he eschews the pragmatism and ‘shift to the centre’ of AMLO, Petro or even in some respects Fabricio Alvarado. However, Bolsonaro has difficulties in forging alliances with other parties to compensate for his weak regional strength.

Conclusions

On the eve of the current electoral cycle, it was widely believed that Latin America was about to experience a ‘shift to the right’, as a new defining political characteristic of the region. Nevertheless, the various elections that have taken place since then have ruled out the idea, at least in part. From the end of 2017 to the present, the results have been quite varied, with victories for very dissimilar candidates situated all along the ideological spectrum: the extreme left (Maduro), the left (AMLO), the centre-left (Carlos Alvarado), the centre-right (Piñera and Mario Abdo Benitez) and the right (Duque).

In reality, the current electoral moment is marked by many distinguishing features in each country, as well as by other characteristics which are common across the region, but the ‘shift to the right’ is not one of them. Latin America is now revealing a series of other traits: for instance, high levels of diversity across the electoral processes, a growing fragmentation of the party system, the persistence of populist and demagogic options, the decline of the traditional left-right cleavage and a trend towards political polarisation.

The common elements that cut across the entire region include the use of elections by the citizens to punish the traditional parties and political classes for the poor functioning of democratic institutions. It is a ‘vote of anger’ against the system –as opposed to an ‘anti-system’ vote– which is cast more ‘against something’ than in ‘favour of someone’. These voters approach the polls with irritation, fatigue and discontent to metaphorically pound their fists on the table and perhaps bring traditional hegemonies to an end. What has intrinsic value for the Latin America voter is that the election might give rise to a change, irrespective of its quality or characteristics.

The ‘anger vote’ is explained by multiple causes but, above all, it is rooted in the profound social change experienced by Latin America since the turn of the century (especially the consolidation and expansion of the heterogeneous middle classes). This has also been accompanied by a cultural change linked to the technological revolution, newly emerging forms of communication and the expansion of social networks. It is in this change that the seed of disaffection giving rise to the ‘anger vote’ can be found.

The ‘anger vote’ prospers in the current socio-cultural context in which the middle-class citizenry is trapped in a vicious cycle by the reigning mistrust of institutions and the spreading mistrust between individuals. Mistrust leads to scepticism, to increasingly demanding standards and finally to hypercriticism, which simply reignites the cycle of ‘mistrust-scepticism-excessive demands-criticism’.

Mistrust, scepticism, high demands and harsh criticism feed the ‘anger vote’. This translates into high levels of citizen disaffection with the political class, the workings of the public administrations and existing democratic institutions. At present, such disaffection is spreading and deepening. In contrast with the past, this sentiment has not resorted to abstention or apolitical behaviour; rather it has begun to shape an electorate in search of a leader to channel its discontent. The malaise has grown, fed by a political and socioeconomic context influenced by economic slowdown, a consolidating and increasingly empowered middle class, the high visibility of corruption scandals and the eroding capacity of states to maintain minimum standards of decently functioning public services.

The ‘anger vote’ has been reactivated by growing citizen malaise and fatigue. The electoral phenomenon will persist as long as economic growth remains weak and expectations for social improvement are unmet. It has fixated on leaders (more than parties or movements) with broad track records within the traditional political system. But while they are not outsiders, neither are they politicians with previous experience in high positions of responsibility at the national level. They attract discontented sectors with demagogic messages from different ideological angles, generating demanding expectations that will be difficult to meet, given party fragmentation, scant fiscal resources and a lack of experience or even sufficient political support.

In circumstances like Mexico’s today, the electorate has chosen to be guided by its anger at the status quo rather than by its fear of the abyss that could open up as the result of pursuing a change that is still shot through with uncertainty. In the words of Luis Rubio, ‘the anger at the status quo –in reaction to the growing evidence of corruption, a closed system of government and a complete disconnect between the citizens and their governors– has won’.

Carlos Malamud

Investigador principal, Real Instituto Elcano | @CarlosMalamud

Rogelio Núñez

Profesor colaborador del IELAT, Universidad de Alcalá de Henares