Original version in Spanish: Las elecciones legislativas de Marruecos de 2016: contexto y lecturas

Theme

On 7 October 2016 the Justice and Development Party revalidated its victory in the Moroccan parliamentary elections.

Summary

After four years at the head of a coalition government existing in a state of subordinate cohabitation with the Moroccan Monarchy, the Justice and Development Party (PJD) emerged victorious once again from the parliamentary elections with a simple majority of the votes cast. The electoral campaign was polarised between the victors and the Party of Authenticity and Modernity (PAM), which had the support of the Monarchy and defined itself as the liberal, secular alternative to the conservative, Islamist model represented by the PJD. Having been charged with forming a government as the party with the highest number of votes, the leader of the PJD is encountering difficulties forging a coalition, in a process that should help gauge the correlation of forces between the Islamist party and the Monarchy.

Analysis

On 7 October 2016 Morocco held parliamentary elections to choose the 395 members of the Chamber of Representatives, the lower house of the Moroccan Parliament, who are elected by universal suffrage. The importance of the ballot in the political life of the country is, however, fairly relative, given that the decision-making centres that govern the legislative sphere continue to lie (as they have since the 2011 Constitution) outside the parliamentary institution itself.

Nevertheless, in light of the singular coexistence of different powers, the nature of the players involved and the role of the country itself in its relationship with the EU and the West in general, the situation in Morocco merits an in-depth analysis.

First, the international, regional and domestic context in which the 2016 elections took place was very different from that of 2011, when the world was still reeling from the aftermath of the ‘Arab spring’. At a regional level, the wars in Syria and Yemen, the emergence of Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State) and the chronic instability in Libya place security issues (refugees and the fight against terrorism) and the search for stability firmly at the centre of the region’s agenda.

Within Morocco itself, the Monarchy has managed to neutralise or at least limit the impact of many of the concessions it was forced to make in response to the 20-F movement (named after the spontaneous demonstrations that sprang up in the country on 20 February 2011). On the eve of the previous elections, the movement demanded a constitutional, parliamentary monarchy in which the Head of State would reign without governing and there would be a true rule of law, demands which the 2011 Constitution failed to satisfy. This climate of change and demands paved the way for the victory of the Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD), which won a percentage of seats that was almost unheard of in the country’s electoral history. The PJD had been growing in popularity and votes since its emergence onto the political scene in 1997, as a result of King Hassan II’s initial attempts to integrate political Islam into the parliamentary workings of the country.

The PJD in government: subordinate cohabitation with the Monarchy

Having won 107 seats and beaten its closest rival (the Istiqlal Party, IP, which won 60 seats) in 2011, the PJD became the leader of a coalition government, as established by the new Constitution which had entered into effect just a few months before. In order to do so, the PJD was obliged to forgo engaging in an open interpretation of the new Constitution, which increased the prerogatives of the Executive while at the same time limiting those of the King.

Throughout the whole term, the leader of the PJD, Abdelilah Benkirane, accepted de facto the pre-eminent role of the Monarchy, and even echoed this position publicly and explicitly in statements and interviews, asserting that ‘leading the government is not synonymous with holding power’ and defining his relationship with the monarch as one ‘based on cooperation and collaboration’. As Prime Minister, Benkirane opted to make concessions in order to gain the King’s trust, rather than to assume a more conflictive stance by launching head-on attacks against the system.

At the beginning of his term, and in keeping with his electoral promises and the climate that characterised that crucial year, 2011, Benkirane did indeed make an attempt to denounce inequalities and corruption (for instance, by publishing the list of transport licences, which reflected a privilege-based system). However, he preferred to deal with these issues as individual cases and prudently avoided going any further, never, for example, denouncing the structural flaws of the rentier state system, which would have clashed with the Palace, the King’s business interests and Benkirane’s own political entourage.

For its part, the Monarchy restructured the Royal Cabinet, appointing royal advisers from among the King’s closest circle to act as a behind-the-scenes government. It also gradually regained control of almost all the ‘ministries of sovereignty’, with the exception of the Justice Ministry, which was assigned in 2011 to Mustafa Ramid, from the PJD. Following the prolonged governmental crisis of 2013, triggered by the IP abandoning the coalition, the Palace regained control of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs (through Salaheddine Mezouar, leader of the National Rally of Independents, RNI), Education (Rachid Belmokhtar) and the Interior (Mohamed Hassad), appointing ministers that reported directly to the King. Meanwhile, economic portfolios (Finance, Fishing, Industry and Trade) found their way into the hands of technocrats from the RNI.

The coalition government headed by Benkirane found its hands tied by the existence within its own ranks of parties with directly opposing ideologies, such as the RNI1 which joined the government after the IP’s withdrawal in 2013. Despite being a member of the government coalition, after the regional elections held in 2015 the RNI supported the main opposition party, the Party of Authenticity and Modernity (PAM), helping it to attain the presidency in five of the country’s 12 regions, even though it had received fewer votes than the PJD.

The PJD has had no choice but to admit that, from inside the government and ministries not under its party’s control, measures have been adopted that go directly against the ideas set out in its electoral programme. These measures include a project to generalise the French baccalaureate (the bac) and put an end to the Arabisation of the school syllabuses, a movement launched by the Minister of National Education within the framework of the instructions given by the King as part of the country’s educational reform. The name of the subject ‘Islamic education’ has also been changed to ‘religious education’. Moreover, the Rural Development Fund has also slipped through the Prime Minister’s fingers, and is now managed directly by Aziz Akhannouch, Minister for Agriculture, whose department is every day becoming more and more like a ‘ministry of sovereignty’, controlled by the Palace.

As regards foreign policy, through the instructions that he gives in his speeches, the King continues to establish the country’s strategic directives in relation to issues such as the Western Sahara, infrastructures and the COP22 Climate Change Conference. The monarch also intervenes in the daily management of the government with his tantrums about the inefficacy of the administration, which the pro-establishment media quickly make public.

Nevertheless, and despite his acceptance of the status quo regarding the Monarchy, Benkirane has somehow managed to remain immensely popular. This is mainly due to his new brand of politics, characterised by his warm, open speaking style, his run-ins with ministers from the royal circles, his use of dialect and his frequent speeches to both Parliament and the media.

Unlike that which occurred during the 1990s and early 21st century during the period of alternance, the PJD has managed to avoid the wear and tear that so often comes with governing. And it has done so despite the heavy cost of reforms such as putting an end to the hiring of civil servants who have not sat a competitive examination, the raising of the retirement age for civil servants and cuts in oil price subsidies. The party’s triumph in the municipal and regional elections of 2015, its clear victory in the major cities and its increasing presence in rural areas attest to the fact that the situation described above has done little to undermine its popularity.

A polarised electoral campaign

In this context, the electoral campaign for the parliamentary elections of 7 October 2016 was polarised between the PJD and the PAM, which, holding the presidency of five of the country’s regions, defined itself as the liberal, secular alternative to the PJD’s Islamist model, using an anti-Islamist discourse that, to a certain extent, was reminiscent of that espoused by the Tunisian party Nidaa Tounes during the 2014 elections in that country.

The PAM focused its attention on the rural areas and the north of the country, through a network of dignitaries with good connections in the administration and a pro-monarchist discourse promising stability. For its part, the PJD, which is a much more militant party, focused on large urban conglomerations and medium-sized cities, in which its popularity is on the rise.

Some months previously, at the beginning of February, the Council of Ministers chaired by the King approved a move to appoint a large number of walis and provincial governors that affected 22 provinces. The newspaper Akhbar al Yom claimed that the move was clearly politically motivated, since the Ministry of the Interior (from whence the proposal had originated) used it as an excuse to promote governors who had previously been appointed to provinces in which the PJD had obtained limited results, installing them instead in ‘large rural provinces in which the PJD had emerged victorious in the local and regional elections’. A serious rift began to emerge between Mohamed Hassad, Minister of the Interior, and Prime Minister Benkirane. It was a rift that would deepen over the following months, becoming evident in gestures such as the repeated demands by the government that the Ministry of the Interior publish a detailed breakdown of the results of the local and regional elections held in September 2015. This information was not made public until June 2016. The rift was also noticeable in the resignation of the Justice Minister Mustafa Ramid from the Electoral Supervision Committee, after accusing his fellow minister Hassad of tampering with the electoral process.

On 18 September, shortly before the start of the campaign, an anti-Islamist protest was organised in Casablanca through the social media. The protest was attended by several thousand people and in its timing certain media organisations claimed to see ‘the concealed hand of the authorities’. With no ‘identifiable organiser’, protesters from the silent, archaic segment of Moroccan society, most of whom arrived in well-organised transports, chanted slogans against the incumbent Prime Minister, Abdelilah Benkirane.

Over previous months, Benkirane had attempted to reposition the PJD as an opposition party to the so-called al-tahakkum system (literally the ‘hidden or de facto powers’ which pull the strings of the government behind the scenes) and the risks posed by the system to the transition towards democracy. This constituted a change in relation to the 2011 slogan: ‘against tyranny and corruption’ (did al-istibdad wa-l-fasad). Despite his position as Prime Minister, Benkirane intimated in his speeches that Morocco had in fact two governments: an elected one and another one controlled by a ‘hidden’ faction. By presenting himself as a victim, he managed to keep his management of the administration out of the spotlight of the electoral debate, while at the same time counteracting the narrative put forward by the PAM, which argued that the division so evident in Moroccan society was between conservatives and modernists. For Benkirane and his political partners, the divide was between democrats and advocates of an authoritarian system, embodied by the PAM.2

This discourse was not well received by the Monarchy. Mohammed VI himself questioned the anti-tahakkum rhetoric in his Speech of the Throne, admonishing those who believed that the King had any preference for any one political party and warning politicians to abstain from ‘exploiting the figure of the King for their own ends’.

Nevertheless, this ideological polarisation cannot quite conceal the convergence between the programmes of the two opposing political parties in economic matters. In this field, the main difference is the PAM’s call for the legalisation of kief, which would ensure the party an overwhelming victory in the provinces in which it is grown, which are precisely those located in the Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, governed by the PAM’s General Secretary, Ilyas El Omari.

However, any ideological debate about the electoral programmes was conspicuously absent from a campaign plagued by leaks and scandals which each contender used to try to discredit his opponents. Some of the scandals that came to light included the import of waste from Italy during the run-up to the COP22 Climate Change Conference; the sale of publicly-owned plots of land in Rabat at knock-down prices to government officials (including Laftit, wali of Rabat; Hassad, Minister of the Interior; and Boussaid, Minister of Finance) and members of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP), such as Malki and Lachgar, in what was considered by Hassad to be a settling of accounts orchestrated by the PJD; and a sex and urfi customary marriage scandal involving two leaders of the MUR, the ideological parent organisation of the PJD.

The PJD has openly accused the Ministry of the Interior of a lack of neutrality during the electoral process, and the ‘Deep State’ of colluding with the PAM. Examples of this, according to the PJD, include the protest in Casablanca –mentioned above– against the Islamisation of society and the ‘exploitation of religion’, which while not expressly authorised by the Ministry of the Interior was nevertheless tolerated by it; the holding up of infrastructure projects in municipalities governed by the PJD; the mobilisation of votes in favour of the PAM in certain areas; and the exclusion of the Justice Minister from the preparations for the elections. Benkirane made his right to form a government in the event of winning the elections crystal clear, yet fearing manoeuvres designed to undermine his position and in an attempt to anticipate the problem of being unable to find the support required to make up a majority, he called for the repetition of the vote should his party fail to forge the necessary coalition.

The problem of the electoral register

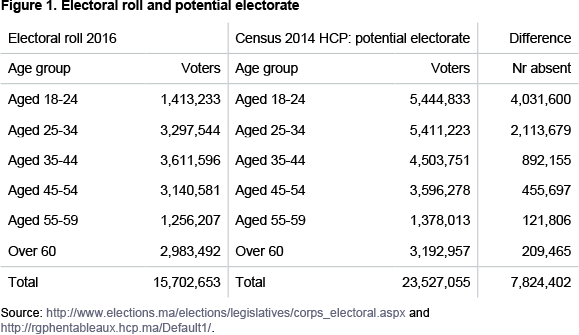

A number of articles3 have pointed out the huge gaps in Morocco’s electoral register, which fails to include 30% of those entitled to vote. According to the general population census conducted in 2014, the country had 33,610,084 inhabitants, of which 23,527,055 were aged over 18. Even excluding those that have died in recent years and those who are not entitled to vote due to their position as soldiers, convicts or certain members of the civil service, such as judges, for example, the potential number of eligible voters is estimated at around 22,874,625.

However, the official electoral register for the 2016 elections included only 15,702,592 potential voters, which means that 7,172,033 Moroccan citizens –almost half the voting population– were excluded from going to the polls. And this does not even take into account the 3 million or so Moroccans living abroad (RME), of whom only the small minority who were present in the country when the register was compiled in 2014 are included. The RME community can only vote by proxy, and only a meagre few chose to use that option in the last elections. This is a major shortcoming that needs to be addressed in future elections in order to lend credibility to the results, since the number of people excluded is extremely high.

The voter turnout in the parliamentary elections of 7 October was officially estimated at 43%, but in truth, if we take those not included on the electoral register into account, the real figure is no higher than 29.5% of potential voters, even without counting Moroccan nationals resident abroad.

The Ministry of the Interior published the electoral register percentages on the official election website, in accordance with age group. Comparing these same age groups with the general population census of 2014, it can be seen that the highest numbers of absences are found among the youngest members of the voting population, ie, those aged between 18 and 24. In this group, a total of 4,031,600 potential voters are not included on the electoral register (see Figure 1). The number of absences drops as we move up the age groups, until the final figure of seven million is reached.

The underrepresentation of urban areas

Morocco has, since colonial times, been a country moving at two different speeds. The composite society to which Paul Pascon referred in his writings was comprised by a modern world centred mainly along the more developed Atlantic coast, and an archaic, intensely rural one, upon which the established power structure relied for its continued dominance. This gaping divide between the urban and rural worlds continued unabated even after the country gained its independence, and its political tradition was characterised by what the late Rémy Leveau termed in his classic work from 1976 Le fellah marocain défenseur du Trône (‘The Moroccan Fellah –farmer–, defender of the throne’). The urbanisation process advanced at a slower pace in Morocco than in other countries in the region, mainly due to a policy designed to limit the rural exodus, which was implemented during the era of Driss Basri, Hassan II’s powerful Minister of the Interior. According to the 2014 census, 40% of the population still lived in rural areas. The political commentator Omar Saghi once wrote in an article that the protesters belonged to ‘that 40% of the population that eke out a living from sub-productive and sub-monetarised subsistence farming, a people enslaved by their native land, illiterate and (as yet) silent. A population that talks with the voice of its master; caidal control combined with the habit of obedience mixed with mistrust of the central power structure’.

This deeply rural Morocco is overrepresented, as evident in sparsely populated electoral districts such as Jerada, Figuig, Bulman and Ifrane, which have between 46,000 and 77,000 inhabitants per seat, whereas the national mean is 110,196 inhabitants per seat.4 At the other extreme, highly urbanised electoral districts such as the prefectures of Casablanca, Fez, Marrakesh and Salé are underrepresented (having between 128,000 and 147,000 inhabitants per seat). The case of the three Saharan regions is particularly telling. In Guelmim-Oued Noun, Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra and Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab the inhabitant-to-seat ratios are just 54,176, 40,775 and 35,516 (respectively), the lowest in the entire country. There can be no doubt that these discrepancies have an impact on the final results in each electoral district.

Analysis of voter turnout and election results

Turnout in these last elections was amongst the lowest in the country’s history, with only 43% of those on the electoral register casting their votes, 1.5% fewer than in 2011. This is extremely worrying, since in addition to the fact that one out of every three Moroccans does not even bother to register to vote, over half of those that do register never actually take the trouble to go to the polls. Moreover, there is also a very high rate of invalid and blank ballots (something which is now traditional in Morocco’s electoral history). These ballots totalled around 1 million during the latest elections, although it is something that the Ministry of the Interior has chosen not to make public on this occasion, thus undermining the credibility of the results.

The extremely polarised electoral campaign, with the PJD at one end and the PAM at the other, coupled with the support provided to the latter party by certain media outlets and official sources, turned the struggle to convince voters into the closest race in the country’s history since 1963, when Hassan II failed to win the parliamentary majority he sought. Article 47 of the 2011 Constitution stipulates that the King must appoint a Head of Government ‘from the political party that wins the most votes in the elections to the Chamber of Representatives’. The contest was between Benkirane and Ilyas El Omari, Secretary General of the PAM and an increasingly influential figure due to his proximity to the Throne.

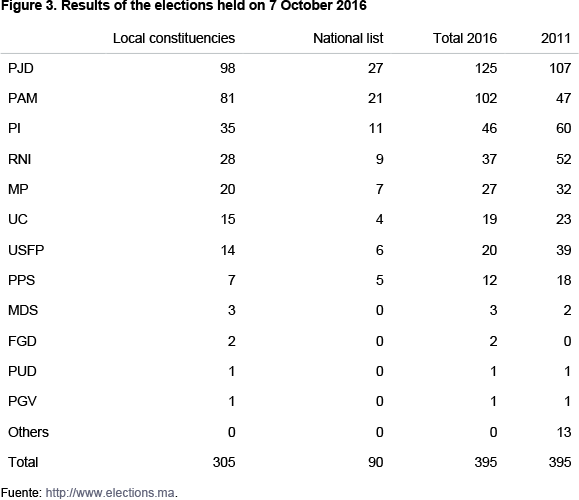

However, in the end, the PJD emerged victorious, demonstrating once again, as in the 2015 elections, that the party’s time in government had done little to undermine its popularity, despite it having adopted a number of extremely unpopular measures. In the local constituencies5 the PJD won 1,571,659 votes, practically the same number as in the previous regional elections, whereas the PAM only won 1,205,444, around 100,000 fewer than in 2015. Both parties improved on their results in the previous parliamentary elections in 2011 (1,080,914 for the PJD and 524,386 for the PAM). All the other parties came in far behind the two frontrunners, since third place went to the Istiqlal Party with 621,280 votes, and the RNI came in fourth, with just 558,875. The results in terms of the seats won are shown in Figure 3.

Conclusions

The PJD won the Moroccan parliamentary elections of 2016, obtaining 16 seats more than in 2011. This result attests to the fact that the party has managed to avoid paying the political price of its subordinate cohabitation with the Monarchy, and its decision not to explore in more depth the possibilities offered by the 2011 Constitution as regards changing the balance of power between the Palace and the elected government. As leader of the winning party (having gained a simple majority of the votes), Abdelilah Benkirane was charged by the King to form a government, an undertaking that will necessarily require the formation of a coalition with other parties.

The negotiations are proving laborious and the outcome will constitute a true test that will help gauge the correlations of forces between Morocco’s leading political party and its Monarchy. Once the PAM (considered by many to be the King’s party) has been defeated at the polls, the Palace is trying to preserve its influence in the government through the actions of a block of ‘administrative’ parties (RNI, UC and MP), under the leadership of Aziz Akhannouch, whose conditions include the exclusion from any future government of the Istiqlal Party. This manoeuvre, described by Benkirane as an ‘attempted putsch against the results of the ballot’, has deadlocked the process and may well lead to a political crisis centred around what the winning party should do in the event of being unable to form a government, a circumstance not contemplated in the Constitution.

Bernabé López García

Emeritus Professor of Arab and Islamic Studies and researcher at the Mediterranean International Studies Workshop (TEIM), Autonomous University of Madrid

Miguel Hernando de Larramendi

Director of the Study Group on Arab and Muslim Societies, University of Castilla-La Mancha | @mhlarramendi

1 A member of what became known, in the lead-up to the 2011 elections, as the G8, a coalition of administrative parties and other smaller groups of a diverse nature.

2 Note that the ex-communist PPS also adopted this approach. Party leader and Minister of Housing Nabil Benabdallah was even admonished in a communiqué published by the Royal Counsel for having identified the tahakkum with the PAM and its founding member, the royal counsellor Fouad Ali El Himma, in one of his speeches.

3 Bernabé López García (2013), ‘La question électorale au Maroc: Réflexions sur un demi siècle de processus électoraux au Maroc’, Revue Marocaine des Sciences Politiques et Sociales, vol. VI, nr 4, February, Rabat, p. 35-63.

4 This figure, calculated using the data published in the Official Gazette of 23 April 2015, would have been much more interesting if the number of people registered in each electoral district had been made public beforehand. The lack of transparency in the publication of previous data and results is one of the main pitfalls of Morocco’s electoral system. It is shocking that the Ministry of the Interior failed to publish the breakdown of the results of the municipal and regional elections until eight months after the vote was held, even after having been repeatedly called upon to do so by the Prime Minister himself. In past eras, although data were often manipulated and were rarely reliable, they were at least published promptly.

5 A total of 305 seats are elected in local constituencies, which correspond to provinces or smaller electoral districts in the case of highly populated cities. The remaining 90 seats are elected through national lists made up by 60 women and 30 young people, as a positive discrimination measure designed to boost the participation in the government of these two groups. In the national list, the PJD won 1,618,963 votes, while the PAM won 1,216,552.