Theme: The crisis and the reforms introduced by the Lisbon Treaty are a double-edged weapon. They entail opportunities for the true Europeanisation of the elections to the European Parliament in May 2014, but also significant risks.

Summary: Five years ago neither had the Eurozone crisis started nor had the changes introduced to the Treaty entered into force. For these two important reasons, the forthcoming elections to the European Parliament (EP) in May 2014 will be very different to the previous ones in 2009. Elections to the EP were traditionally a set of separate national polls presented by national political parties as second-rate versions of domestic elections. Issues affecting the EU and its policies were rarely the key issues under discussion. However, the current crisis in Europe has brought the EU and its policies to the centre of the political debate in all of the EU’s member states, without exception. Furthermore, for the first time since the first direct elections to the EP in 1979, European citizens in May 2014 will be electing a Parliament whose composition will eventually determine who is elected head of the Commission, the so-called EU executive. Some commentators expect the changes to eventually mobilise the electorate and produce the sort of legitimacy the Union has failing to achieve since its creation. Constraints and opportunities will have to be balanced if the EU is to engage its citizens in a truly pan-European electoral process that will boost its legitimacy. But the process will not be without its share of technical difficulties. First, it is not that simple to obtain candidates to ‘fight’ the elections. Secondly, a highly EU-centred political campaign in the context of the current crisis could give rise to highly Europhobic parliament. Thirdly, while it is expected that politicising the elections by linking them to the election of the President of the European Commission will make them more ‘interesting’ to the voters, both the EP and the Commission may see their institutional role undermined and/or put to question.

Analysis

The crisis and the Lisbon Treaty: two decisive factors for a ‘different’ type of elections

For years the elections to the European Parliament (EP) have been considered second-rate events. It was understood that little if anything was at stake. The perception was not entirely ill-founded as the election results influenced had no influence on the appointment of the President of either the European Commission or the Council –the two institutions that set the course of the EU’s political direction–. Additionally, national parties had so far refused to focus their campaigns on issues related to EU integration, preferring to give the priority to issues related to national politics.

Given this background, it is hardly surprising that the elections to the European Parliament have stubbornly shown two distinct trends.

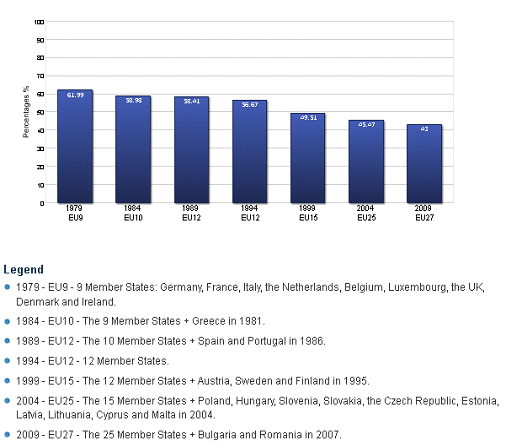

Graph 1. Turnout at European elections, 1979-2009

Source: European Parliament Website.

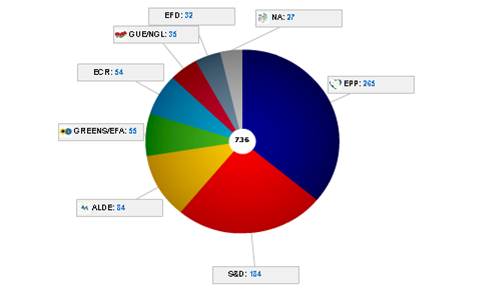

First, as shown on Graph 1, turnout has decreased dramatically, to the extent that voter participation in EP elections has dropped from 62% in 1979 to a record-low 43% in 2009. Secondly, voters have used these elections to punish parties in government or to vote for parties that they would not otherwise vote for in national elections. This explains, in part, why minority parties –including Europhobic parties– gain considerably better results in European elections than in national ones. As shown on Graph 2, a significant number of the seats in the 2009 EP were held by MEPs from political parties other than the European Peoples Party (265) and the European Socialists (184). However, the 2014 European elections are taking place in a substantially different context to all previous ones. Hence, the trends prevailing up to now might come to an end.

Graph 2. Composition of the Constituent 2009 European Parliament

Source: European Parliament Website.

For the first time, electors will indirectly choose the person who will lead the European Commission. This is because the President of the European Commission will be chosen according to the terms of the Lisbon Treaty, which provides that it will be the responsibility of the EP. Thus the head of the ‘EU Executive’ is elected on the basis of a proposal made by the European Council taking into account the European elections (article 17, paragraph 7 of the TEU). This is a significant improvement since the Treaty of Nice only provided for the EP to approve the designation of the President of the Commission.

In order to fully implement the spirit of the Lisbon Treaty and to make full use of its new prerogatives, the EP approved a resolution [1] urging the political groups to nominate candidates for the Presidency of the Commission. The candidates are expected to play a leading role in the electoral campaign and are expected to present the political programmes of their respective groupings in each member state. This is a historic change. For the first time there is ‘something’ at stake in the elections to the EP and, furthermore, something that can easily be understood in terms of political choices for the electorate. Voters will be able to ‘put a face’ on their vote. For the first time political parties in the member states are expected to make it clear to the electorate which European political family they belong to and which candidate they are supporting.[2] This means that for the first time in the history of the elections to the EP it will be possible to see a truly pan-European campaign.

Many analysts argue that the changes could play a role in boosting public awareness and interest in the EU elections. Indeed, according to the Eurobarometer,[3] 73% of Europeans believe that more information about candidates’ European political affiliations would encourage people to vote, while 62% think that having party candidates for the Presidency of the Commission and a single voting day would help boost the turnout. In addition to linking the results to the election of the Commission’s President, the Lisbon Treaty has significantly improved the EP’s position in the EU’s political architecture. The so-called co-decision procedure will become the ordinary procedure in almost all initiatives, making the EP and the Council co-legislators. The EP will also decide on the entire EU budget together with the Council. However, these powers are unlikely to attract more electors to the polling stations.

In addition to the changes brought about by the Lisbon Treaty, the 2014 European elections will take place in a very particular context. The current crisis has brought the EU and its policies to the centre of the political debate in the member states and the ‘debate over Europe’ is likely to stay there during the next European campaign. Unlike previous elections, the EU and its future policies are likely to dominate the campaign. Additionally, national parties have been asked[4] to nominate their candidates ahead of the elections so as to allow the candidates to mount an EU-wide campaign that concentrates on European and not on national issues, as was the case in previous elections. This is a novelty for a type of elections that for years have been fought in national terms and have excluded issues regarding European integration and/or European policy choices, including the type of European integration supported by the various contenders. However, it is still unclear whether or not there will be a truly pan-European debate on the EU’s political choices, including the type of European integration to be pursued during the new parliament’s five-year term.

Will the 2014 EU elections be so different?

In the forthcoming elections the electorate will be able to clearly identify the different political options available and ‘put a face’ (the future President of the European Commission’s face) on the different political options. Thus, it should be easier for Europeans to choose their preferred model of European integration. This challenges the previously perceived ‘irrelevance’ of the elections to the EP in terms of political choices. In addition, the various bailouts and subsequent austerity measures have put EU policies on the political agenda of every member state. Voters are increasingly realising how decisions taken in ‘Brussels’ affect specific policy choices in their own member states. In this context, the current crisis provides an opportunity for establishing the necessary political dialogue in every democratic polity between electors and those to be elected. Unfortunately, the crisis has also generated a discourse that sees the EU as part of the problem rather than as part of the solution. Even worse, there is a feeling that democratic policies in the EU have been bypassed and the crisis has aggravated the trend. As an example, the EU’s finance ministers met in May 2010 and as a result the Union’s economic governance was reshaped overnight. Many historic decisions followed, including the creation of a €750,000 stability mechanism for the Euro. In the meantime, several member states –particularly Greece and other countries in the Eurozone periphery– were asked to apply austerity measures.

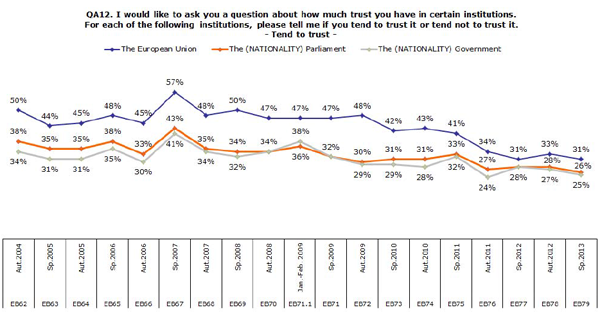

This is the paradox of the EU crisis. On the one hand, the relevance of the EU’s political choices have been clearly revealed; on the other, some see the EU as the villain of the piece, dictating unpopular economic policies to its member states. According to a recent Eurobarometer survey,[5] the level of trust in the EU’s institutions has fallen to a historical low of 60%. This is part of a general trend of decreasing levels of trust in political institutions, as shown on Graph 3. The idea that sharp cuts in public spending have been ‘imposed’ by the EU, together with the increasing distrust towards the EU, provides ammunition for the Europhobic parties to run successful campaigns that encourage voters to cast an anti-EU ‘protest’ vote. Another possible scenario is that alienated voters will simply choose not to vote.

Graph 3. Evolution of trust in national governments and parliaments and in the EU (August 2004 to September 2013)

Source: European Commission, Eurobaromerter Public Opinion in the EU, July 2013.

In both cases, the EPmight find itself facing problems of a different nature. The European elections might see a strong mobilisation of voters in favour of radical nationalist and anti-EU parties. A recent Gallup poll[6] highlighted that Euroscepticism is on the rise even in traditionally pro-EU countries like France, where a third of respondents said they would vote to leave the EU in the event of a referendum being held. Another study,[7] based on public opinion data gathered from all 28 EU member states in July-August 2013, found that overall as many as every seventh MEP could be a right-wing Eurosceptic.

In addition, two potential risks should be considered when linking the results of the EP elections to the election of the President of the Commission. First, from an institutional point of view, politicising the EP’s elections by linking them to the appointment of the President of the European Commission may not be the most obvious way of preserving the Commission’s institutional role or the EP’s. The Commission’s role as an impartial ‘guardian of the Treaties’ will undoubtedly be questioned if its President is elected on the basis of an ideological campaign. However, in any case, the President’s cabinet will continue to be determined by a delicate bargaining process between member states and political groups. Conversely, the EP’s role as the body entrusted with providing parliamentary control might eventually be questioned if a majority in the Parliament is seen to be trying to protect ‘its’ President. Secondly, it might not be easy to find the ‘right’ political figures to run for President of the European Commission. This might lead Europe’s citizens to have to elect the parties’ ‘second choices’. In theory, it should not be very difficult for each political group to choose a candidate. However, so far only the Party of the European Socialists and the Party of the European Left have declared their choice. The reticence of the other parties might have to do with the fact that it is not clear why ‘top political figures’ will take the risk of presenting themselves to be elected President of the European Commission while the positions of President of the European Council, President of the EP and President of the Eurogroup, in addition to High Representative/Vice-President of the Commission, will be chosen in a less politically risky manner, probably beyond public scrutiny.

Conclusion: The forthcoming elections to the EP in May 2014 will be different to all of its previous elections since its establishment in 1979. On the one hand, the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon has changed the rules of the game. Electors will be voting for both the EP’s membership and the President of the European Commission. Furthermore, candidates are expected to present their programmes in every member state. This change in the rules provides an enormous opportunity for the development of EU-wide political campaigns based on issues related to European integration, which could break the tendency of European elections being treated by both political parties and electors as second-rate elections where ‘nothing’ is at stake. In addition, the current economic crisis has already brought the ‘issue of Europe’ to the political arena in all member states and it is likely remain there at least until the elections. National parties have a great opportunity to run well-structured and well-thought-out political campaigns that could provide the necessary debate on the ‘political choices’ they would like to see in the EU. In other words, Europe’s citizens can have the possibility of choosing –for the first time– what type of European integration model they would like to see implemented during the next five years.

Parties might accept the challenge but it still seems a very risky business for ‘top politicians’, especially when the other ‘top EU jobs’ will be assigned in a more secretive manner in which the ‘losers’ will not be disclosed. The rising Euroscepticism generated by the crisis and the perception that the EU is more part of the problem than a solution might not encourage national parties to risk annoying their traditional voters with a highly EU-centred political campaign. However, the risk of not doing so is to leave a free rein to the Europhobic parties. Thus, both the crisis and the reforms introduced by the Lisbon Treaty are a double-edged sword. If used carefully, knowing the danger involved, they might not only boost voter turnout but also serve to explain ‘Europe’ to its citizens and to break the trend of European elections mainly being an excuse for national parties to practice their political campaigns for the next national elections while an apathetic public choose to either ‘experiment’ with their vote or simply ignore the ‘noise’.

Daniel Ruiz de Garibay

PhD candidate at the Department of Politics and International Relations of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

[1] European Parliament Resolution of 22 November 2012 on ‘The elections to the European Parliament in 2014’(2012/2829(RSP)).

[2] European Parliament Report of 12 June 2013 on “Improving the practical arrangements for the holding of the European elections in 2014”, (2013/2102(INI)).

[3] European Commission, Flash Eurobarometer 364 – TNS Political & Social, March 2013

[4] European Parliament Report of 12 June 2013 on “Improving the practical arrangements for the holding of the European elections in 2014”, (2013/2102(INI)).

[5] European Commission, Eurobarometer Public Opinion in the European Union, July 2013

[6] Gallup 2014 EU Election – The French and the EU June 2013

[7] See Policy Solutions’ analysis: The left could win next year’s EP elections. Access 11.11.13