Also available the Spanish version: Objetivo 2030: los flujos financieros ilícitos

Theme

Target 16.4 in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (Agenda 2030) is a global commitment to reduce the level of illicit financial flows and the damage they do. The target stands as a great achievement by civil society organisations, bringing a complex set of issues from the wilderness to the international agenda. But there remain critical challenges, both technical and political, if progress is to be realised.

Summary

‘Illicit financial flows’ is an umbrella term which covers cross-border movements related to tax avoidance, tax evasion, regulatory abuses, bribery and the theft of state assets, the laundering of the proceeds of crime and the financing of terrorism. While international organisations had been somewhat active in relation to grand corruption and money laundering, it was only with the growing drive of civil society organisations from the early 2000s that the focus shifted to reflect the importance of tax-motivated flows.

Because the necessary expertise was also concentrated there, civil society can claim an unusually large degree of credit for two key differences between the Sustainable Development Goals framework and their predecessor the Millennium Development Goals, which ran from 2000 to 2015. While the latter completely overlooked any role for taxation in development, the new Agenda 2030 not only includes a target devoted to reducing illicit financial flows but also establishes the importance of tax as the primary target in goal 17, related to the overall implementation.

Target 16.4 is not the end of the story, however. Perhaps because of a lack of deep expertise among policymakers and international organisations, both the target and the outline indicator on illicit financial flows suffer from poor drafting. The indicator is likely to be among the last to be confirmed in the entire framework and substantial technical challenges remain. But there are now concrete proposals on the table and an active process underway to test and confirm their potential.

Analysis1

This brief paper aims to provide a background to the Sustainable Development Goals target 16.4. To that end, it contains three main sections. The first explains the rise of the tax justice movement and of the related umbrella term ‘illicit financial flows’ as a case study in both civil society influence and Southern leadership in international policymaking. Evidence on the scale and impact of illicit flows is also briefly surveyed here.

One of a number of key successes has been the achievement of target 16.4 itself; but this has also brought to the surface a series of technical and political challenges that are yet to be fully resolved. The second section addresses these challenges.

Finally, the third section presents the proposed indicators for target 16.4 which are currently under discussion in the UN process. Despite the inevitable difficulties of providing summary indicators for such complex phenomena, and of doing so in such a way that policy progress can be meaningfully assessed and policymakers held accountable, there are reasons to be broadly optimistic. The success of the tax justice movement over the past 15 years has laid the grounds for the necessary transparency.

(1) The rise of tax justice and IFF: a brief history

(1.1) The roots of tax justice

When the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were under discussion in the late 1990s, tax was a sorely neglected issue in international development research and policy analysis. On top of that, there is some truth in the caricature of the MDGs as entirely donor-led, so the complete absence of tax from the framework eventually adopted was neither altogether surprising nor seriously contested. But the MDGs did, however, contribute to a powerful dynamic that the next time –if there was to be one– there would have to be genuine ownership among countries at per capita income levels.

By the time of the MDGs’ launch in 2000, however, a progressive agenda around tax had begun to emerge. This was most obvious in the UK, where Oxfam published the first paper on the threat posed to development by ‘tax havens’, estimating a revenue loss of US$50 billion a year, and the still-new government of Tony Blair released a white paper on globalisation which highlighted variously the importance of taxing multinationals, ‘an important mechanism for sharing the gains from globalisation between rich and poor countries, and for reducing poverty’ (p.57), that offshore financial centres ‘can offer cover for tax evasion, capital flight and the laundering of illegally acquired funds that can be particularly harmful to developing countries’ (p.58), and identifying transparency as an important part of the solution.2

Over the next few years, discussions grew in intensity internationally, not least via the European Social Forum. As a direct result, in 2003, the Tax Justice Network (TJN) was formally established as a network of experts and activists in all walks of tax and policy life: economists, lawyers, accountants, political scientists and more, many of whom had professional experience in public policy, academic research and campaign activism. The set of related concerns is a wide one, but at its core are three overlapping issues: (1) the scale of tax evasion and tax avoidance; (2) the pivotal role of tax havens; and (3) the resulting damage to human rights and human development, globally.3

By 2005,4 TJN had laid out the core policy platform that would, 10 years later, become the entire basis for the global policy agenda –that was initially written off as utopian and unrealistic–. This platform is the ABC of tax transparency:

- Automatic, multilateral exchange of tax information.

- Beneficial ownership (public registers for companies, trusts and foundations).

- Country-by-country reporting by multinational companies (public).

At the same time, the ‘4Rs of tax’ had begun to be established as a framing of the positive benefits that effective and just tax systems can provide:5

- Revenue: the central importance of tax in ensuring that governments can provide administrative functions and core public services.

- Redistribution: tax, along with the direct and indirect transfers that tax revenues provide for, is the key mechanism by which societies can limit gross inequalities in income, wealth and opportunity facing individuals and also groups (including by gender, ethnolinguistic group and disability).

- Re-pricing: the potential of effective tax systems to ensure that market prices fully reflect social costs and benefits (eg, of tobacco consumption or carbon emissions).

- Representation: perhaps least appreciated but most important is the role of tax in building the social contract between citizens and with the state. The share of tax revenues (and direct taxes most of all) in government expenditure is one of the few indicators consistently associated with improvements in governance. When states increase their reliance on taxing citizens, the prospects are not only of more revenue but –crucially– that the revenues will be better spent, reflecting social preferences through enhanced political representation.

(1.2) A new umbrella term: illicit financial flows

In 2005 the US businessman Raymond Baker published a book about his experience of blatant tax abuses by multinational companies during his many years working in Nigeria and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa.6 The NGO he established, Global Financial Integrity (GFI), went on to popularise the term ‘illicit financial flows’ to refer to the wider range of phenomenon that the UK white paper had bracketed together: tax abuses, corruption and the laundering of the proceeds of crime. Crucially, Baker argued that the ‘old’ agenda of corruption as a problem of lower-income countries was responsible for just a limited percentage of the overall total –while tax-related behaviour, including trade price manipulations by multinational companies, was the greatest part–. In this way, and through GFI’s subsequent estimates of around US$1 trillion a year of illicit financial outflows from lower-income countries, the umbrella term IFF came to popular usage.

Inevitably, such estimates are associated with a high degree of uncertainty: (1) because they attempt to quantify phenomena which are by their very nature deliberately hidden; (2) because they seek to estimate a wide range of phenomena with a single methodology; and (3) because they rely on publicly available information which is unfortunately limited.7 But they have clearly contributed to keep illicit flows in the spotlight.

Alternative approaches have tended to focus on individual IFF types. Estimates of undeclared offshore assets have ranged from around US$8 trillion to as much as US$32 trillion, with associated revenue losses conservatively estimated to approach US$200 billion annually. The greatest research focus has been on the tax avoidance of multinational companies, with estimates by IMF and Tax Justice Network researchers of around US$500 billion to US$600 billion annually, of which around US$200 billion is suffered by lower-income countries –representing a disproportionately large share of their actual tax revenues–.8

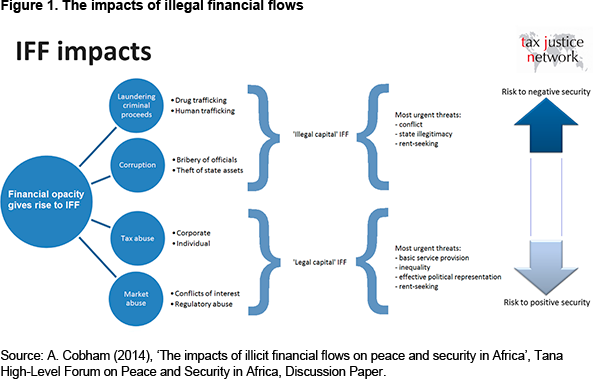

The impacts of illicit financial flows are many and varied, but the common element is that IFF are corrosive to the state’s legitimacy and capacity to act, which in turn undermines the achievement of human rights and development. Figure 1 above highlights just some of these effects, and two key categories can be identified.

Most simply, IFFs weaken state revenues. Global estimates of the losses to multinational tax avoidance and individual tax evasion through undeclared offshore assets run into the hundreds of billions of US dollars each year. While the losses are likely greatest in absolute terms in the richest economies, the losses are most intensely felt in lower-income countries. To be specific, the losses are estimated to account for a systematically higher proportion of current tax revenues in lower-income countries.9 Since these are also the countries with lower per capita spending on crucial public services such as health and education, it is likely that in addition the losses translate most directly into forgone human development progress. Non-tax IFF will also aggravate the impacts, through the diversion of economic activity into illegal markets when they generate hidden profits and through the diversion of public assets for private gain. More broadly, markets will work less well, rent-seeking activities will proliferate at the expense of productive activities and so economic growth is also likely to be inhibited.

The second category of IFF impact is on governance –and therefore on the likelihood of any given revenues being well spent–. The damage here occurs in multiple ways. Illegal market IFFs such as those related to drug trafficking are also associated with a loss of state control and even legitimacy, as criminal actors become more powerful. Grand corruption moves a state along the spectrum from a broad-based provision of public benefits to private capture. Tax-related IFFs compound the issue. IFFs militate against effective taxation and against direct taxation in particular –thus undermining the most important of the four Rs of tax, a representative state. The evidence shows, for example, that governments more reliant on tax revenue are not only likely to spend more out of each dollar of revenue on public health, but that independently of the financing level public health systems are also likely to achieve greater coverage.10

And so, countries facing higher IFF are likely to exhibit higher inequalities, weaker public services, poorer governance, lower growth and –above all– markedly worse prospects for the progressive realisation of human rights.

(1.3) Southern leadership and a new consensus

In this context, it was perhaps surprising that the post-2015 framework has come to differ so sharply from the MDGs. There are at least three major differences between the MDGs and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These can be summarised as ownership, implementation and inequality.

In terms of ownership, the MDGs were caricatured as a creature of the donors, a plan to spend aid for the achievement of limited improvements in some basic human outcomes. While not entirely unfair, such a characterisation does not do justice to the substantial progress that was achieved over the period on extreme poverty measures –nor to the growing ownership among lower-income country policymakers over the period–. Nevertheless, the frustration of many was clear, and it was evident before the post-2015 discussions began in earnest that no repeat would be permitted. The SDGs would reflect much more than a limited donor agenda of meeting basic needs.

This shift is reflected clearly in implementation. Where the MDGs contained no verifiable targets for higher-income countries, neither in terms of their own human development progress nor in terms of their contribution to others, the SDGs are universal in coverage and include clear measures reflecting both national and international implementation responsibilities. And where tax was not even mentioned in the MDGs, it provides the very first target in implementation goal 17.1. This also reflects the logic of aid-recipient-countries’ determination to exert greater ownership.

Finally, the topic of inequality was almost entirely absent from the MDGs. Arising at a moment when the progressive challenge to the World Bank’s extreme-poverty focus was the UNDP’s Human Development Index (fighting to ensure extreme lack of income was at least joined by consideration of extreme lack of health and education), the MDGs inadvertently incentivised an approach that targeted the easiest first. The greatest progress could be made by shifting the members of a population nearest the poverty line in question, above it –while those furthest away could be left for some later time–.

The SDGs, in contrast, speak of inequalities in every breath. The mantra of ‘leave no one behind’ is resoundingly backed by a framework that, for many goals, rewards no progress that is not fully shared by the most marginalised groups. While proposed targets on individual inequality were heavily diluted or excised, the issue remains central: and with it, a hugely important and as yet unmet commitment to ensure the data are available to hold policymakers accountable.11

Within this set of shifts, Southern leadership was perhaps most powerfully demonstrated in the issue of IFFs. In the early MDG period at least, ‘corruption’ featured as a reason why aid was not more effective. The Corruption Perceptions Index came to great prominence despite its reliance on the perceptions of a small, international elite and its high correlation with per capita incomes –to say nothing of giving top marks to the likes of Switzerland and Singapore, now rightly seen as providing financial secrecy that drives corruption elsewhere–.12

The crucial moment in establishing IFFs on the international development agenda came with the formation of a high-level panel under the auspices of the UN Economic Commission for Africa and of the Africa Union, and chaired by former South African President Thabo Mbeki.13 The report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows out of Africa, delivered after three years of evidence gathering and political engagement, does not shirk from identifying national and regional responsibilities but is also explicit about the critical roles played by financial secrecy jurisdictions such as Switzerland and by multinational companies, and hence about the international responsibilities of each.

With wider G77 and civil society support, the report created an irresistible basis for the inclusion of IFF in the post-2015 framework. The UN Secretary General’s own High Level Panel, co-chaired by the heads of state of Indonesia, Liberia and the UK, discussed illicit flows including multinational tax avoidance at length, and recommended an explicit, if vague target:

‘Reduce illicit flows and tax evasion and increase stolen-asset recovery by $x’.14

In the absence of any noticeable dissent, and with the energetic support of G77 members and many civil society organisations, the proposal was carried unopposed into the final SDG framework.

(2) Technical and political challenges: defining IFF

Regrettably, perhaps, the broad support for the thematic focus on illicit flows led to a failure to challenge the specific framing of the proposed target. The final target agreed globally, SDG 16.4, combined references to other illicit activity but kept the key features –namely, the emphasis on reducing the dollar scale of IFFs and the failure to disaggregate the umbrella term into its component parts–:15

16.4. By 2030, significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organized crime.

16.4.1. Total value of inward and outward illicit financial flows (in current United States dollars).

The direct result of this is that there are now significant technical challenges to establishing an agreed methodology for the single IFF indicator, 16.4.1 (or indeed to create space for additional indicators). To construct a single dollar-value indicator for all IFFs raises three problems.

First, such an approach requires consensus on a single methodological approach (and data sources) for a group of quite distinct phenomena that are unified only by the fact that they are deliberately hidden by using a range of financially opaque channels. All estimates are inevitably subject to some uncertainty and so reaching a consensus is inevitably fraught with difficulty.

Secondly, addressing the target and indicator to the umbrella term hampers the possibility of using more robust approaches to the estimates of some of the underlying components –potentially adding to the difficulty of reaching consensus on an estimation approach–.

Third, and perhaps most importantly for the prospect for progress, targeting the level of IFFs at a global level only risks having no meaningful accountability. Which policymakers, after all, can be held responsible for the global IFF trend? If outflow estimates can be disaggregated to the national level, there may be more meaningful accountability for the countries that suffer IFF –rather than those that are ultimately responsible for the financial secrecy and the multinational companies that drive IFF–. The following section lays out proposals currently under consideration in the UN process, which seek to address the technical challenges.

An important political challenge also exists. The indirect result of failing to disaggregate the umbrella term is that lobbyists have identified the potential to subvert the target, specifically by seeking retrospectively to remove the multinational avoidance element. This lobbying has been visible in the positioning of various OECD and EU countries in related UN processes, prompting conflict with G77 members and others.16 In the technical discussions of the SDG 16.4 indicators held in Vienna in December 2017, for example, the representative from a lobby group for multinationals, the International Tax and Investment Center, called repeatedly for the exclusion of avoidance.17

Some supporting voices have challenged the inclusion of avoidance on the grounds that the definitions used are sometimes unclear or contradictory,18 but that is to ignore the history of the term’s emergence and the pre-eminence given to avoidance in both the high level panels’ reports that underpinned the SDG agreement and the underpinning development of tax-justice issues.19 A contemporaneous independent expert analysis by the U4 Anti-Corruption Centre confirms the central role of counter-avoidance measures in the illicit flows discourse at the point the SDG target was agreed.20

We might try to construct an alternative view, in which the repeated emphasis on combating avoidance in the context of the post-2015 framework was somehow not intended to lead to the inclusion of avoidance in the IFF target. If we rule out the possibility that the high-level panels and many others were highlighting avoidance in order for it not to be included anywhere, then the remaining possibility would be that it was intended for avoidance to be addressed elsewhere in the framework. The only logical alternative to 16.4 would seem to be target 17.1, which addresses the level of tax in general:

17.1. Strengthen domestic resource mobilisation, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection.

17.1.1. Total government revenue as a proportion of GDP, by source.

17.1.2. Proportion of domestic budget funded by domestic taxes.

To the best of my knowledge, however, there was never a serious proposal by member states or a UN body, even for the level of disaggregation necessary to treat corporate tax here21 –to say nothing of revenue losses to multinational avoidance–. It is impossible, therefore, to conclude that the intention of the high-level panels and the subsequent member-state agreement was anything other than for multinational tax avoidance to be included under SDG 16.4.

(3) Concrete proposals for concrete progress

As things stand, the indicator/s for 16.4 will be among the last to be set. While lobbying pressure to exclude avoidance may not gain further traction, the technical challenges posed by the loosely drawn target remain substantial. A range of alternatives are discussed in our paper prepared for UNCTAD (with Petr Janský).22 Within the constraints of the current design we propose two indicators that reflect the breadth of tax-related IFFs and also include one major outcome of illegal market IFFs also (undeclared offshore wealth).

It is interesting to note that both indicators depend on data only now becoming available, following the work of civil society to promote the policy platform established in the early 2000s. Specifically, the two indicators rely on data generated by the ‘A’ and ‘C’ of the Tax Justice Network’s ABC of tax transparency.

(3.1) Profit shifting: SDG 16.4.1a

For IFFs related to multinationals’ avoidance of corporate income tax we propose an indicator of misaligned profits based on OECD country-by-country reporting data. A clear advantage of this approach is that the data should provide a precise measure for all multinationals above the OECD reporting threshold of the misalignment of profit away from the locations of real economic activity. Issues of estimation can therefore be set aside completely. Since profit shifting is made up of lawful and unlawful avoidance, along with criminal evasion, this will inevitably contain a degree of lawfully achieved profit misalignment. Since the agreed aim of the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting process (BEPS) was to curtail the degree of misalignment, however, it is uncontroversial to embed this direction of travel in the SDGs (while reflecting that the value of the indicator consistent with IFF elimination need not be absolute zero).

The misaligned profit indicator is defined as the value of profits reported by multinationals in countries for which there is no proportionate economic activity of MNEs. It is defined for each jurisdiction and it can be summed across some or all countries, allowing both the global number required by the SDG indicator and also the disaggregation that will support accountability for individual governments –whether they obtain profit shifting or suffer it–.

(3.2) Undeclared offshore assets: SDG 16.4.1b

This policy measure is intended above all to address offshore tax evasion by individuals. The category of undeclared assets, however, –and hence the proposed indicator– should include the results of the great majority of illicit flows except those related to avoidance. With only certain exceptions, maintaining the success of the illicit flow will require continuing not to declare ownership of the results of offshore assets to the home authorities.

The proposal is to use aggregate data gathered under the OECD Common Reporting Standard (CRS), which requires financial institutions to confirm the citizenship of accountholders in order to exchange individual data with the home-country authorities. The undeclared offshore assets indicator is defined as the excess of the value of citizens’ assets declared by participating jurisdictions under the CRS, over the value declared by citizens themselves for tax purposes –in other words, the total offshore assets undeclared–.

Assuming participation by countries to report aggregate data, the indicator would also allow both a global total for SDDG reporting, and a country-level and bilateral breakdown to support accountability of policymakers, both in countries suffering tax evasion and in jurisdictions holding the underlying assets. In this paper we explore the potential of the two indicators if the UN framework requires a single indicator only –although separation is clearly desirable if allowed–.

Conclusions

The last two decades have seen the emergence of a powerful tax justice movement globally, led by civil society expertise and increasingly by policymakers of the global South. One significant marker of progress has been the establishment of a target to address illicit financial flows, including offshore tax evasion and the tax avoidance of multinational companies, as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. While technical and political challenges remain, progress on civil society’s policy platform for tax transparency means that the data is available to construct robust indicators with the potential to drive change by ensuring accountability at the national level –including the many jurisdictions that benefit from facilitating tax abuses and corruption elsewhere–.

Alex Cobham

Chief Executive, Tax Justice Network and Visiting Fellow, King’s College, London | @alexcobham

1 The contents of this paper were discussed at an Elcano Royal Institute seminar in April 2018, sponsored by the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation. The author would like to express his gratitude to the seminar participants for their comments, particularly Iliana Olivié and Aitor Pérez, and to the discussants Raquel Cabeza and Antonio del Campo.

2 Oxfam (2000), ‘Tax havens: releasing the hidden billions for poverty eradication’, Oxfam GB Policy Paper; and HMG (2000), ‘Eliminating world poverty: making globalisation work for the poor’, White Paper on International Development, HM Government, London.

3 Brief history of the Tax Justice Network.

4 TJN (2005), Tax Us If You Can, Tax Justice Network, London.

5 A. Cobham (2005), ‘Taxation policy and development’, Oxford Council on Good Governance: Economy Analysis 2.

6 R. Baker (2005), Capitalism’s Achilles Heel: Dirty Money and How to Renew the Free-Market System, John Wiley, London. See also http://www.gfintegrity.org/about/.

7 A current TJN project is the open writing of a book devoted to providing a comprehensive critique of the methodologies and data of the leading estimates of illicit financial flows.

8 See TJN (2017), ‘Tax avoidance and evasion: the scale of the problem’, Tax Justice Network Briefing.

9 A. Cobham & L. Gibson (2016), ‘Ending the era of tax havens: why the UK government must lead the way’, Oxfam Briefing Paper.

10 P. Carter & A. Cobham (2016), ‘Are taxes good for your health?’, UNU-WIDER Working Paper, nr 171.

11 A. Cobham (2014), ‘Uncounted: power, inequalities and the post-2015 data revolution’, Development, vol. 57, nr 3-4, p. 320-337.

12 A. Cobham (2013), ‘Corrupting perceptions’, Foreign Policy.

13 United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, & African Union (2015), Report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa.

14 United Nations (2013), ‘A new global partnership: eradicate poverty and transform economies through sustainable development’, Report of the High Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. Note that while publication of this report preceded that of the UNECA/AU panel report, the early discussions and public documents of the former had already set the tone.

15 See https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg16.

16 For example, the UNCTAD Intergovernmental Group of Experts on Financing for Development (November 2017) saw a prolonged debate among member states before finally agreeing policy recommendations that include avoidance as part of IFF: ‘[The Group] Stresses the need for redoubling of efforts to substantially reduce illicit financial flows by 2030, eliminating them, including by combating tax evasion and corruption through strengthened national regulation and increased international cooperation, to reduce opportunities for tax avoidance and considering inserting anti-abuse clauses in all tax treaties, to enhance disclosure practices and transparency in both source and destination countries, including by seeking to ensure transparency in all financial transactions between Governments and companies, with respect to relevant tax authorities, and to make sure that all companies, including multinationals, pay taxes to the Governments of the countries where economic activity occurs and value is created, in accordance with national and international laws and policies’.

17 The organisation (ITIC) has published plans, co-authored by the representative in question, to promote a tax agenda for lower-income country policymakers that focuses attention away from multinationals. The report was recently taken down from their website but can be found at Archive.org. ITIC is, however, perhaps best known for its years of tax lobbying on behalf of tobacco companies.

18 M. Forstater (2018), ‘Illicit financial flows, trade misinvoicing and multinational tax avoidance: the same or different?’, CGD Policy Paper, nr 123.

19 See, eg, A. Cobham (2017), ‘The significance and subversion of SDG 16.4: multinational tax avoidance as IFF’, remarks delivered at ECOSOC Forum on Financing for Development follow-up.

20 U4 (2014), ‘Combating illicit financial flows: the role of the international community’, U4 Expert Answer.

21 Related suggestions were made by civil society, including in the global thematic consultations, but to no avail. On 17.1 and the separation from the IFF target, see also this discussion from the time.

22 A. Cobham & P. Janský (2017), ‘Measurement of illicit financial flows’, UNCTAD Background paper for UNODC-UNCTAD Expert consultation on the SDG Indicator on Illicit financial flows, nr 12-14, December.