Theme: In the ongoing negotiation of the MFF 2014-2020, Spain has to balance several interests, requiring a flexible position combined with some firm principles.

Summary: If it had not been for the sovereign debt crisis, the negotiation of the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2014-2020 would have been the leading topic during these months.The current negotiation is taking place at a time when budget consolidation requires the limitation of public expenditure, including the EU budget, although the need for growth-oriented policies is increasing. In this respect, the next MFF could be a good opportunity to shape Europe’s future.

The negotiation is also of particular importance to Spain, for several reasons. First, over the past few years Spain has experienced a significant change in both financial and economic terms, which has altered its financial situation in relation to the EU budget. Secondly, the country is in the midst of an economic crisis, in the context of a severe sovereign debt crisis in the Euro Zone countries. This is a new element to take into account in the negotiations: the Spanish position will reflect this transition and will need to strike a balance between different objectives. Hence, Spain’s negotiating position will not be static, but will have to have the flexibility necessary in each stage of the negotiating process. Furthermore, because of its likely new role as a net contributor, Spain’s general position in the negotiation will be based on the objective of achieving an agreement on the revenue system in parallel to the discussions on EU expenditure, and it should try to leave all options on the table.

Analysis

The New Spanish Position: A Balancing Act

The role of Spain within the EU budget has undergone an amazing transformation: from being the largest net beneficiary in absolute terms in the MFF 2000-2006, with net returns of 1.2% of GDP, to being a potential net contributor starting in 2014. As a ‘cohesion country’, together with Ireland, Portugal, Greece and the 12 new member States, Spain has been the leading net recipient of cohesion funds in absolute terms, absorbing almost 25% of the EU budget devoted to regional policy at the beginning of 2000. After 2007 the first place has been taken by Poland, but Spain is still the second largest beneficiary for the period 2007-2013. The reasons for this transformation are various and partly contrary to the recent trends imposed by the economic crisis. In this respect, Spain’s new financial situation in relation to the EU budget is still not very clear and only the final agreement on the MFF 2014-2020 will show to what extent and in which way the Spanish net balance will change.

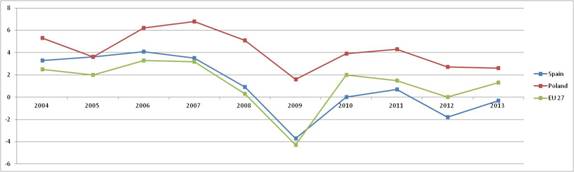

On the one hand, Spain recorded an outstanding economic development up to 2007, with growth rates above the EU average. This made Spain’s budgetary situation one of the best in the Euro Zone and fostered the convergence of the Spanish regions towards the EU average. Another factor, with an impact on the returns from the EU budget, was the ‘statistical effect’, the virtual rise in the EU’s per capita GDP as a result of the incorporation of 12 new member states in 2004 and two new member states in 2007, which now absorb 50% of the EU’s cohesion funds.[1] Due to this effect, Spain managed to obtain a phasing-out process for the Cohesion Fund as well as for some of its poorest regions and maintained its status as a net beneficiary of EU funds even in the context of EU enlargement.

On the other hand, Spain has been one of the European countries to be most heavily affected by the economic crisis and is currently making enormous efforts to consolidate its public finances. The new member States have performed relatively well in recent years due to the resources from the EU budget but also because of their economies’ increasing competitiveness.

Moreover, in this difficult context, the EU budget does not envisage any instruments to take decisive action to help member states overcome situations such as the current crisis, and focuses primarily on investments in less-developed regions and specific sectors, which do not necessarily correspond with Spain’s needs.

Graph 1. Real GDP growth rates in Spain, Poland and the EU-27[2]

Source: Eurostat (2012).

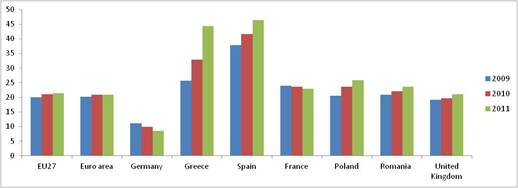

Furthermore, within the debate on a more proactive role for the EU in overcoming the crisis, a growing number of member states are resisting further austerity demands and would prefer to focus the MFF 2014-2020 on growth and job creation.[3] This new role for the EU budget could be of special interest to Spain, if it can address the problems affecting growth and employment –particularly youth unemployment–.

Graph 2.Youth unemployment in EU Member States

Source: Eurostat (2012).

In the worst-case-scenario, Spain will become a net contributor during the MFF 2014-2020. However, its likelihood depends not only on the final agreement but also, among other factors, on the data used to calculate the GNI of eligible regions. In this respect, the Spanish government has already requested that the most recent data be used in order to adequately reflect the impact of the crisis on the country and its regions.

The Spanish government’s preferences are therefore different from those it put forward in the negotiations for MFF 2007-2013 and it will have to manoeuvre between calls for stronger commitments in Cohesion Policy, on the one hand, and fiscal consolidation, on the other. Spain has to balance the arguments of a net contributor, which aims to minimise the ‘national’ contributions to the EU budget, with the demands of a beneficiary, which defends EU spending. In any case, the Spanish government will try to avoid becoming an ‘excessive’ net contributor and will probably continue to defend the principles of ‘gradualism in changes’ and ‘proportionality in effort’.

Maintaining such a balance will also be evident in Spain’s negotiating strategy. While in the negotiation of the MFF 2007-2013 Spain participated proactively in the ‘friends of cohesion’ group, in the current negotiations it has been cautious and only recently committed to the group.[4] Conversely, Spain has not taken part in the net-contributors’ initiatives or participated in the new ‘friends for better spending’ group.[5] The Spanish government is alert to any changes that might be introduced in terms of spending and revenues and is attempting to keep all its options open.

Hence, the Spanish negotiating position is likely to be dynamic, not static, and to evolve according to the negotiation process. The government rejects the ‘salami theory’, pursued by the Danish EU Presidency: the salami (the MFF 2014-2020) is cut into slices and the entire salami is impossible to see.[6] This means that all budgetary headings should be open until specific figures are on the table and until the final agreement is negotiated. According to this theory, an agreement on the revenue system should be reached in parallel to the discussions on expenditure.[7]

The State of Negotiations

During the past months considerable efforts have been expended in approximating the member states’ positions. While the Polish EU Presidency mostly pursued a ‘bottom-up’ approach, the Danish EU Presidency was more proactive and presented for the first time its MFF 2014-2020 ‘negotiating box’ at the General Affairs Council meeting on 26 March. The ‘negotiating box’ outlines the main elements and options for the MFF negotiations, including the question of own resources, but leaves open the most important conflicting issues. During the first semester of 2012 the General Affairs Council has discussed all headings of the expenditure side and intends to start the debate on own resources. The General Affairs Council of 29 May held a first discussion on a consolidated version of the ‘negotiating box’ covering all elements of the MFF negotiating package. Ahead of the EU summit, on 28-29 June, the European Council’s President, Herman Van Rompuy, sent a questionnaire to the member states on the MFF 2014-2020 in order to frame the debate around the role the EU budget should play for growth and job creation. However during the European Council the MFF was far from being the focal point of attention. The discussions did not advance and concentrated primarily on the overall size of the MFF 2014-2020. Finally, the EU leaders reaffirmed their ambition of reaching an agreement before the end of the year. Nevertheless according to the results of questionnaire, the idea that the MFF 2014-2020 should play an important role in stimulating growth appears to be gaining ground.[8]

Although the Danish Presidency made some progress, the member states are still divided on several key elements of the European Commission’s proposals.[9] Two broad groups of opinion can be identified: the ‘friends of cohesion policy’[10] and the ‘friends of better spending’. The debate between the two will dominate the following months. While the first focuses on the fact that the Commission’s budgetary proposals for MFF 2014-2020 constitute an absolute minimum, the second insists on the need to limit public spending and considers that the quality of spending is the key to creating additional growth, even with a limited budget. In order to reach a deal before the end of 2012, the MFF will be discussed by the member states during the European Councils in October and December. In addition, the Cyprus Presidency has already scheduled an informal General Affairs Council on this issue for 30 August.

The Spanish Government’s Priorities in the Negotiations on the MFF 2014-2020

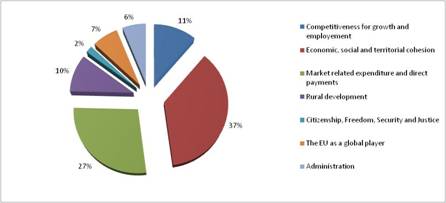

(1) The new Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). In the European Commission’s MFF proposal, the amount of expenditure devoted to the CAP remains on the downtrend as adopted at the previous MFF and will tend to be equivalent to the expenditure on Cohesion Policy.

Spain is the second-largest recipient after France in the MFF 2007-2013 and receives nearly €7,500 million per year from this budget heading. In the future MFF the CAP will also be an important element (even more so than Cohesion Policy) in improving the country’s net balance and the aim is to continue to receive at least the amounts initially proposed by the European Commission. A further reduction of the CAP would mean a clear loss in direct payments and market expenditure and, as a result, directly affect the living conditions of farmers. On the contrary, the Spanish position highlights the CAP’s ‘multi-functionality’, which impacts positively on environmental and market issues. The new CAP should improve the sector’s competitiveness and include effective measures to strengthen the position of both producers of agricultural goods and the food industry. The CAP must ensure the future for European agriculture and offer clear prospects for farmers, supporting the production of agricultural products. Related to this, Madrid also called for the continuation of aid within the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund for adjusting fishing-fleet capacities and modernising vessels.

In addition, the reformed CAP should contribute to the goals of the EU 2020 strategy, as indicated by the Spanish EU Presidency in the European Council of March 2010. In this respect, the proposed increase in funds for R&D in agriculture is welcome.

During the last few years Spain has made significant efforts regarding the ‘greening’ of agriculture and feels prepared to implement the new requirements without difficulties. Nevertheless, the obligation to link 30% of direct aid to the implementation of new environmental measures is set too high. Spain has traditionally been, and continues to be, against the renationalisation of aid, especially against proposals to co-finance the ‘first pillar’.[11]

Graph 3. MFF for the EU-27

Source: COM(2011) 500 final.

(2) The Cohesion Policy and EU 2020. From being the largest recipient of EU regional aid, at around 25% of the total for the 2000-06 period, in 2007-13 it will fall to second place, behind Poland, and account for 12% of total funds.

The Spanish government considers it a priority to have a Cohesion Policy that is a continuation of the current system but that also introduces improvements. The EU 2020 strategy is an essential element for the design of all future EU policies and should especially be a criterion for allocating funds to the Cohesion Policy. In this respect, there are arguments in favour of giving a greater importance to unemployment criteria (especially youth unemployment) and to additional criteria such as the technology gap, innovation rates and the rate of immigration.

Nevertheless, the main priority is to establish fair gradual exit strategies for the Spanish regions that are leaving behind the Convergence Objective. For these regions the Spanish government demands specific transition periods in order to avoid abrupt changes in the funding they receive, to guarantee financial stability and to allow them to continue to converge with the more prosperous regions.

Furthermore, the Spanish government reiterated its traditional demands for a specific treatment within the Cohesion Policy for the Canary Islands, as an ultra-peripheral region, as well as for Ceuta and Melilla, as remote border towns, as was achieved in previous negotiations.

According to the Spanish government, which insists on more simplification and transparency in funding, the proposed provisions related to the conditionality of funds are considered to increase the system’s complexity. The new conditionality mechanisms will link the national budgetary performance to the receipt of the funds. Hence, the beneficiaries will be subject to pre-conditions –to be met even before any funds are distributed– and post-conditions, which, if met, will reward states with additional funds.

One of the new elements of the European Commission’s proposal for the MFF 2014-2020 is the Connecting Europe Facility, which will help improve the existing patchwork of European transport, energy and digital networks and create cross-border links where they are missing. The government expressed its concern that this new instrument could undermine the member states’ priorities for the trans-European transport network. Another issue of concern is the increased co-financing rates proposed by the European Commission for this new instrument. In times of fiscal austerity it is very difficult to co-finance projects with 60% or 80% of the total costs and it would be helpful to reduce the rate of co-financing in the first few years of the MFF and increase it progressively thereafter.

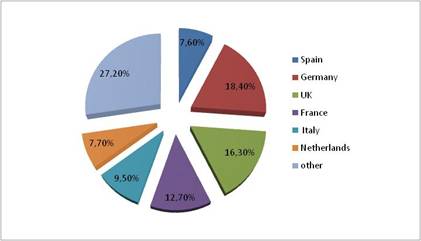

(3) R&D policies. The resources for projects related to R&D have been growing over the past few years. Spain could increase its share in the EU Framework Programme and –in the first four years of the 7th Framework Programme (2007-10)– the sixth-largest recipient of funds for R&D in the EU-27.

Graph 4. Structure of participation in the 7th Framework Programme (2007-10)

Source: CDTI (2012).[12]

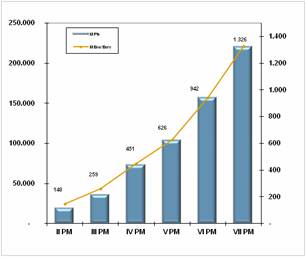

Graph 5. Spanish participation in the Framework Programmes

Source: CDTI (2012).

During the negotiation of the MFF 2007-2013, the Spanish government made a special emphasis on the so called ‘digital or technological gap’ between member states and on the need to promote capacities for innovation not only with the R&D policy but also with the regional policy. Although the situation has improved, the gap between EU member states is increasing. Hence, the Spanish government also wants the negotiation of the MFF 2014-2020 to introduce into the EU budget some instruments to close the technological gap.

The Spanish government has repeatedly stressed the importance of financing innovation-oriented policies and research within the EU as the key to the success of the EU 2020 strategy, and supports the promotion of SMEs both in the future Framework Programme (Horizon 2020) and in the programme for the competitiveness of enterprises and SMEs (COSME). There is also a special focus on tourism projects in the new COSME instrument, as it is one of the Spanish economy’s vital sectors. However, support should not only be based on criteria of ‘excellence’, which provide a static picture of the actual situation, but also on a broader idea of ‘convergence in R&D’ across the EU. In this respect, the Spanish position is to demand criteria that will allow countries that are making a significant effort –but which have not yet reached excellence– to access the funds in order to enhance their R&D capacities.

(4) Additional issues. With regard to the heading ‘security and citizenship’, the government has said that a common security and defence policy, as well as police and judicial cooperation (specifically Frontex and Eurojust), need more financial resources in order to function effectively according to their mandates. The EU should also increase its efforts on issues related to immigration. The proposal to create a single instrument for integration and asylum questions has been considered a positive step.

With regard to heading 4 (Global Europe), the Spanish position criticises the reduction in funds for bilateral cooperation with Latin America, which has been a traditional priority. According to the government, several Latin American countries, such as Peru, Colombia and Ecuador, are more vulnerable than other geographical regions, and this is not adequately taken into account by the new EU Instrument for Cooperation with developed countries.

The EU’s external action is considered a priority by the Spanish government, which stresses the importance of the European External Action Service, as well as the efforts to fight poverty and fulfil the commitments on climate change. In line with the general consensus among member states, the Spanish government also supports the idea that the European Development Fund (EDF) should remain outside the MFF.

(5) EU Own Resources. With regard to financing, the approach will be to equip the EU with sufficient resources to meet future challenges and demand a financing structure that is based on the principles of fairness and transparency. This is coherent with Spain’s position in previous MFF negotiations, where it has traditionally defended a ‘progressive’ GNP resource, based on GNP per capita, which would mean higher payments for richer countries. The government has also been traditionally critical about VAT, which is considered to be regressive in nature. Within the negotiation on the MFF 2014-2020 the Spanish government supports a financing structure of the EU budget based only on Traditional Own Resources and GNP, eliminating all compensation and correction mechanisms, and has recently shown support for a new European resource, the Financial Transaction Tax, as proposed by the European Commission. Spain is in favour of the proposed reform of own resources and of the introduction of new own resources. According to the European Commission, a financial transaction tax, if adopted as a new own resource for the EU budget, could reduce member-state GNI-based contributions by 50% in 2020 –an outcome which would be favourable for Spain, regardless of whether or not the country becomes a net contributor or a net beneficiary by that time–.

Conclusions: In the ongoing negotiation of the MFF 2014-2020, Spain has to balance several interests. This will require a flexible position combined with some firm principles. It will probably need to include different elements into its position, such as R&D policy and the EU 2020 strategy, but on the other hand will have to take into account the specific characteristics of the Spanish economy, such as the emphasis on small and medium-sized enterprises and the agricultural sector, as well as the impact of the economic crisis, a new factor that was not present in previous negotiations. It may need to leave aside its traditional character of ‘cohesion’ country and become a ‘competitiveness’ country, focusing its efforts on the ‘transition regions’, which will gradually move away from fulfilling the conditions for receiving structural funds from the EU budget.

In this respect, the traditional Spanish position on policies such as CAP and Structural Funds will have to be updated and modernised, while bearing in mind that both policies are the main source of funds from the European budget. At the same time, the main objective should also be to avoid becoming an excessive net contributor and to maintain a gradualist approach in any changes in financial position as regards Europe. The specific situation of the Spanish economy, in the midst of a deep economic crisis, will also be a new and important factor. In moments of crisis, financial negotiations are even more important and the funds from the EU will be even more valuable.

Mario Kölling

García Pelayo Fellow, Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales, Madrid

Cristina Serrano Leal

PhD in Economics

[1] C. Serrano Leal & M. Kölling (2009), ‘Spain and Budget Reform in the EU’, Working Paper nr 12/2009, Real Instituto Elcano.

[2] Data for 2012 and 2013 are Eurostat estimates.

[3] M. Kölling & C. Serrano Leal (2012), ‘Austerity vs Stimulus: The MFF 2014-20’s Role in Stimulating Economic Growth and Job Creation’, ARI nr 24/2012, Real Instituto Elcano.

[4] A group of countries formed in 2004 to defend the important role of Cohesion Policy and comprising the new member states plus Portugal, Greece and Spain.

[5] Austria, Germany, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden.

[6] ‘Intervention of the Spanish Secretary of State for European Union Affairs, I. Méndez de Vigo y Montojo, at the Joint Committee for European Affairs of the Spanish Parliament’, 17/IV/2012, DSCG, Comisiones Mixtas, nr 17.

[7] C. Serrano Leal (2011), ‘Capítulo 9. Financiación: El Presupuesto’, in Beneyto, Maillo & Becerril (Coords.), Tratado de Derecho y Políticas de la Unión Europea, Aranzadi Thomson Reuters, vol. III, p. 492-993.

[8] Two questions were been put to the EU’s leaders in order to streamline the debate at the European Council: ‘How can the different policies in the new MFF best contribute to the creation of growth and jobs and enhance the quality of EU spending?’ and ‘How should we prioritise spending among the different policy areas and better align it with the Europe 2020 strategy?’. ‘Van Rompuy Frames Debate around Growth and Targeted Spending’, Europolitics, 26/VI/2012.

[9] Kölling & Serrano (2012), op. cit.

[10] The following countries signed the ‘friends of cohesion’ statement: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Rumania, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and Slovenia.

[11] Méndez de Vigo y Montojo, op.cit.

[12] CDTI (2012), Informe de la participación española en el VII PM (2007-2010).http://www.cdti.es/index.asp?MP=7&MS=39&MN=3&TR=C&IDR=60&IDP=54&IDS=6.