Theme: The growth in foreign direct investment in Spain in 2013 underscores the increased international confidence in an economy that is beginning to recover from a five-year recession, albeit weakly.

Summary: Gross foreign direct investment (FDI) increased 8.8% in 2013 to €15.8 billion and net investment after deducting divestments was 36.3% higher at €11.9 billion. Both figures exclude special purpose entities (SPEs) and hence are productive investment.[1] FDI has long played an important role in the economy, and investment opportunities are growing.

Analysis

The importance of foreign investment in the economy

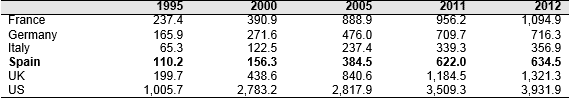

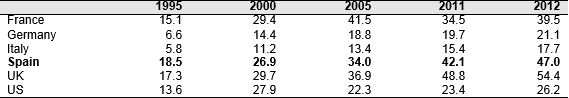

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has long played a prominent role in the Spanish economy, particularly since the 1959 Stabilisation Plan, which ended the policy of autarky that followed the 1936-39 Civil War and began to open up the economy. The inward FDI stock stood at US$634.5 billion at the end of 2012 (latest comparative figure according to UNCTAD), up from US$110.2 billion in 1995 (see Figure 1). Among the world’s 15 largest economies, Spain’s FDI stock in GDP terms (47%) is higher than the US’s, France’s, Germany’s and Italy’s (see Figure 2). FDI inflows have ranged from a high of 26.4% of gross fixed capital formation in 2000, when the economy was in the middle of a long boom period, to a low of 3% of GDP in 2009 (10.8% in 2012), when the economy entered a five-year recession that ended in 2014.

Figure 1. Inward FDI stocks by selected countries (US$ billion), 1995-2012

Source: World Investment Report 2013, UNCTAD.

Figure 2. Inward stock of FDI (% of GDP), 1995-2012

Source: World Investment Report 2013, UNCTAD.

Inward FDI surged after Spain joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1986; at times it seemed as if the country was up for sale. Liberalisation opened up opportunities for foreign companies in a country with a sizeable domestic market, growth potential and the possibilities of using Spain as a platform for exports. These factors assumed as much if not more importance than wage levels, where the gap relative to the then EEC-15 had been narrowing fast until devaluations in 1992 and 1993 began to restore competitiveness.

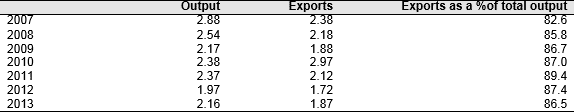

Spain’s motor industry, the world’s 8th-largest producer of cars, which generated 14.5% of merchandise exports in 2013, has been entirely owned by multinationals since 1986 when Seat, founded in 1950 with Fiat’s assistance, was sold to Volkswagen (see Figures 3 and 4). Multinationals are also strong in cement (Portland and Lafarge Asland), an industry in the doldrums since 2008 because of the collapse of the property sector, steel (ArcelorMittal), electrical appliances (Sony, Philips and Electrolux), electronic components (Siemens and Robert Bosch), electronics (Philips and Honeywell), information technology (IBM and HP) and some consumer products (Unilever and Procter & Gamble). Barclays, Citibank and Deutsche Bank have retail networks, but their share of the market is small. The foreign presence in insurance (Allianz, Axa, Aviva and Generali) is larger than in banking. The French Auchan (known in Spain as Alcampo) and Carrefour groups led a revolution in Spanish retailing, opening hypermarkets that lured customers away from traditional corner shops.

Figure 3. Top-15 car producers, 2013 (millions of units) (1)

(1) Excluding commercial vehicles.

Source: OICA.

Figure 4. Output and exports of cars and industrial vehicles (million), 2007-12

Source: Anfac.

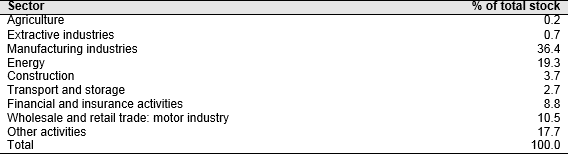

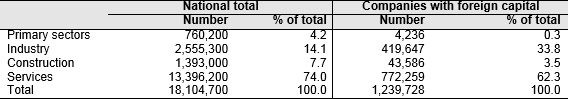

In 2011 (latest figure available), 36.4% of the stock of foreign investment in Spain was in manufacturing industries (see Figure 5). Companies with foreign capital provided employment to 1.23 million people in 2011 out of a total of 19.3 million jobholders (see Figure 6). The annual turnover of foreign affiliates in Spain is around €400 billion (40% of GDP).

Figure 5. Distribution of foreign direct investment in Spain by sector, 2011 (% of total) (1)

(1) Excluding special purpose entities. See the definition at http://glossary.reuters.com/index.php?title=SPV.

Source: Registry of Foreign Investments.

Figure 6. Employment by sectors

Source: National Statistics Office (INE) and Registry of Foreign Investments.

Improved international confidence

International investor confidence in the Spanish economy has improved significantly. This is reflected in the sharp drop in the risk premium on 10-year government bonds over the benchmark equivalent German bonds –to below 200 bp this year (177 bp on 24 March), down from a peak of 637 bp in July 2012–, and the exit in January from the €41 billion bailout of some banks by the European Stability Mechanism. Government bond yields are at less than half the level they reached in 2012. The current account was in surplus last year (0.7% of GDP) for the first time in 27 years, thanks to a significant degree, to the continued growth in exports.[2] The deficit reached 10% in 2007. In recognition of the re-balancing of the economy, Moody’s upgraded Spain’s sovereign credit rating one notch to Baa2 in February with a positive outlook.

There have been several landmark investments in recent months: the acquisition by Berkshire Hathaway, run by Warren Buffett, of Caixabank’s life insurance business for €600 million, the purchase by Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, of a 6% stake in the construction giant FCC for €113.5 million and the €7.2 billion purchase of the broadband company ONO by Vodafone, the world’s second-largest wireless carrier.

Emilio Botín, the chairman of Banco Santander, the euro zone’s largest bank by market capitalisation, told reporters while on a visit to New York last autumn, ‘We are living a fantastic time, money is arriving from everywhere’.

The labour market is more flexible, as a result of the government’s reforms in 2012. Spain’s staggeringly high unemployment rate of 26% (more than double the euro zone average) is due not only to an unsustainable economic model, excessively based on the construction and property sectors, but to higher firing costs and the dual and dysfunctional labour market split between insiders (those in a privileged situation on permanent contracts) and outsiders (those on fixed-term contracts). The reforms have lowered firing costs for workers on permanent contracts and given companies greater flexibility to negotiate their own deals with their workers and not be bound by centralised sector-wide collective bargaining agreements, A new permanent contract has also been introduced for companies employing fewer than 50 people (95% of total employment in Spain).

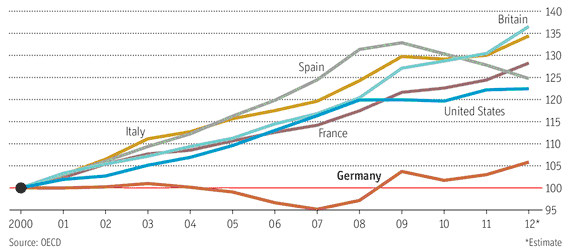

Unit labour costs (ULCs), a component of cost competitiveness, have been on a downward trend since 2008 (see Figure 7). They declined 0.4% in the fourth quarter of 2013 over the third quarter, with the fall outpacing the decrease in productivity. ULCs in the OECD area increased 0.1%. Spain has regained around half of the competitiveness it lost before the crisis.

Figure 7. Unit labour costs (2000 = 100)

The government has also halted the fragmentation of the domestic market. Parliament approved the law to guarantee the unity of the market last December. This enables companies to operate throughout Spain with a single licence as they no longer need permits to operate in each of the country’s 17 regions, as could happen in the past. Different regions imposed different rules on companies, deterring them from expanding outside their home market. In one of the more absurd examples cited as a reason for the new measure, a company making slot machines had to manufacture 17 different models in order to meet the requirements of each regional government.

There is little room, however, for triumphalism: the unemployment rate will not return to the pre-crisis level of 8% (high by the standards of countries such as the US) until 2025, according to the research department of BBVA. The previous economic model, excessively based on bricks and mortar, was labour intensive but unsustainable. When the property bubble burst, jobs were quickly destroyed. The challenge is to move toward a more sustainable and knowledge-based model, but this will take a very long time.

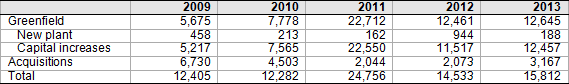

Gross investment in 2013, second highest in last five years

Gross investment in 2013 was 8.8% higher at €15.8 billion, the second-highest figure in the last five years (see Figure 8). Net investment after deducting divestments was 36.3% higher at €11.9 billion, as a result of a drop of 82% in divestments (from €22.7 billion to €4.0 billion).

Figure 8. Gross foreign direct investment in Spain, 2009-13 (€ billion) (1)

(1) Excluding special purpose entities.

Source: Registry of Foreign Investment.

Almost 80% of the gross investment were capital increases, while new ventures only accounted for 1% and acquisitions the rest. Investment was concentrated in four sectors: financial and insurance activities (€3.1 billion, +42%), manufacturing industries (€2.6 billion, -38.5%), real estate (€1.7 billion, +66.7%) and construction (€1.4 billion, -21.7%) accounted for 57% of the total.

Investment funds have been snapping up at bargain prices real estate repossessed by banks or in the hands of the ‘bad bank’ Sareb, set up to absorb the souring assets of eight lenders. Property prices have fallen on average by more than 30% since the bursting of the property bubble in 2008. Sareb’s first sale was made last April when the private equity firm HIG Capital acquired around 1,000 homes valued at €100 million. Hedge fund managers George Soros and John Paulson have both taken a €92 million stake in a new property investment vehicle called Hispania.

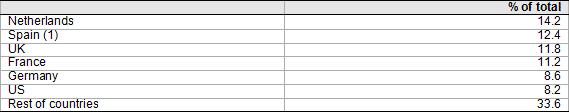

The main investor country was the Netherlands with 14.2% of the total (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Foreign direct investment in Spain by country of ultimate origin in 2013 (% of total)

(1) Investment by Spanish companies via their subsidiaries abroad or jurisdictions such as Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

Source: Registry of Foreign Investments.

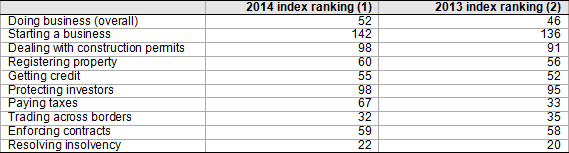

Spain’s lower position in the World Bank’s annual Ease of Doing Business does not seem to have affected investment. Spain dropped to 52nd out of 189 countries in the 2014 index from 46th position in the 2013 index (see Figure 10). There has, however, been a marked improvement in the maximum number of days required to satisfy the requirements to start a business –to 23 from 47 in 2005–. Yet this is still far more days than Germany (14) and France (6), however. Companies, however, often are up and running in less than 23 days.

Figure 10. Ease of doing business Index: Spain’s rankings

(1) Out of 189 countries, benchmarked to June 2013.

(2) Out of 185 countries, between June 2010 and May 2011.

Source: Doing Business reports, World Bank.

Prospects

The motor industry is moving into a higher gear, judging by the spate of recent announcements such as General Motors’ decision to invest €210 million in its plant in Zaragoza, the company’s largest in Europe, following an investment of €170 million in 2013. The plant will start producing this year the Mokka SUV. GM workers agreed a wage freeze for 2013 and 2014 to help the plant compete better with others in Europe. The Michelin group is to invest €25 million in its factory at Valladolid, in addition to the €30 million being invested in its plant at Aranda del Duero, while Germany’s Bayer invested €6 million in its plant in Asturias so that it can produce the entire global aspirin output. In one of the first industrial investments in Spain by China, the industrial holding Boer Power acquired Temper, an electrical equipment company that was immersed in insolvency proceedings.

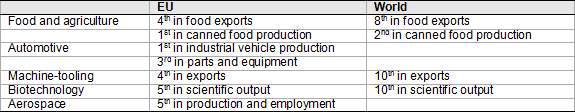

The Consejo Empresarial para la Competitividad (Business Council for Competitiveness) has identified six sectors which are particularly promising for foreign investment as they are not only internationally competitive but have proved to be more resilient to the crisis than others, thanks to their growing international focus, innovation and highly-qualified personnel in a context of lower labour costs compared to competitors. They are: the automotive sector, biotechnology, food and agriculture, ICTs and audiovisual, aerospace and machine-tooling (see Figure 11). These added value sectors generate around 35% of exports and employ more than 2 million people.

Figure 11. International positioning of key Spanish sectors

Source: Business Council for Competitiveness.

Conclusions: The good foreign investment news follows record exports in 2013, helping to put Spain back on the road to recovery. The challenge is to maintain the momentum and remain competitive.

William Chislett

Associate Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute and author of three books on Spain published by the Institute. Oxford University Press published his latest book on Spain last September

[1] See the definition at Financial Glossary Reuters .

[2] See the author’s report Spain’s exports: the economy’s salvation.