Original version in Spanish: Las relaciones hispano-chinas y el COVID-19: luces y sombras de una cooperación imprescindible para España.

Theme

The COVID-19 crisis may be a turning point for China’s foreign relations. This paper analyses its impact on Spanish-Chinese relations, an issue of particular importance from a European perspective.

Summary1

As to whether COVID-19 will bolster or erode China’s international influence, for the time being there is no qualitative change in Spanish-Chinese relations. This does not mean that the crisis has no bearing on the evolution of bilateral relations, as it has, but rather that it boosts different trends that balance each other out. China has established itself as a key partner for Spain while at the same time certain governance shortcomings and limitations to its cooperation have become apparent. This has increased the perception of China as a threat amongst the Spanish public, which at the same time has come to identify China as its second preferred ally outside the EU. Furthermore, relations with China are entering Spain’s political debate for the first time due to the far-right VOX.

Analysis

The coronavirus crisis has once again shown that China and Spain are two countries that provide help to each other when in difficulties. When the pandemic hit China the hardest, the Spanish authorities sent medical supplies to China twice –at the end of January and in the first week of February–. The aid shipments were jointly arranged with the UK and took place in a context of high-level political support by the Spanish authorities to the Chinese community in Spain, to the people of China and to their leaders.

On 4 February the Spanish Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, met representatives of the Association of Chinese Residents in Spain at the Moncloa Palace to convey his solidarity and support in the face of the health emergency in China and to reject any stigmatisation of the Chinese community in Spain. The following day, the Head of State, King Felipe VI, expressed his explicit support to the measures taken by the Chinese authorities to fight the coronavirus: ‘Spain values very highly the critical efforts and measures put in place by the Chinese government to achieve an effective management of this crisis that affects us all; and it has expressed from the very beginning its willingness to cooperate with China, in whatever is in its power to help contain and overcome it’. Spanish gestures of goodwill to China have been welcomed by both the Chinese authorities and the media and were the prelude to the subsequent cooperation Spain received from China.

Since the second half of March, when the health emergency decreased in China but intensified in Spain, aid flows have been channelled in the opposite direction. China’s central and local governments, the Chinese business sector, as well as the Chinese community in Spain, have all mobilised to assist Spain in its fight against coronavirus. The most significant Chinese public donation –on 22 March– came from the central government and comprised 834 diagnostic kits for 20,000 people, 50,000 face masks, 10,000 gowns, 10,000 protective goggles, 10,000 pairs of gloves and 10,000 pairs of shoe covers. In addition, several Chinese local governments such as Fujian, Gansu and Nanning have donated medical supplies to Spanish local governments with which they have cooperation agreements (respectively Cantabria, Navarra and Murcia).

Among private donations, those of the chairmen of Huawei and the Alibaba group –both with a significant presence in Spain– are particularly noteworthy and have been explicitly praised by Spain’s Royal Family. The volume of Chinese private donations has exceeded public ones and involved direct talks between Chinese business leaders and the Spanish authorities. In addition, the Chinese community in Spain –more than 225,000 people– was actively mobilised throughout the country to make donations of medical supplies, especially to hospitals and law enforcement institutions as shown in many videos and social networks posts. The Chinese community also acted as a liaison between Spanish administrations and Chinese medical providers.

China has been the basic provider of the medical supplies purchased by Spain’s central and regional governments to face the pandemic. The amount of contracts signed to acquire medical material and supplies from China exceeds €726 million, among which stand out the €628 million from Spain’s central government and, among the regional governments (‘Autonomous Communities’), €35 million from Catalonia and €23 million from Madrid. This has made evident both the essential role of China as the only country capable of supplying such a volume of medical material at a time of crisis and the various challenges in doing business in the country. Despite significant monitoring by Spanish officials and authorities, transactions with China have not been without problems, such as shipments of defective products, lack of required technical specifications and the failure to meet deadlines.

Chinese public policy in action

The Chinese authorities are well aware that the COVID-19 crisis may have a significant impact on the country’s position within the international community. The scale of the threat and its possible origin in Wuhan have led multiple players within and outside China to question the role of the Chinese authorities in the origin and management of the crisis, stressing governance shortcomings such as an ineffective regulation of the consumption of meat from wild animals and the lack of transparency.

In this context, Chinese public diplomacy is being very proactive in sharing a narrative about the coronavirus crisis that improves China’s international image. That is the case in Spain, where Chinese diplomacy stresses the speed and effectiveness of the sanitary and economic measures adopted in China to face the crisis caused by the coronavirus, quoting the support received from various international institutions such as the World Health Organisation and the International Monetary Fund.

In Spain, when referring to the coronavirus, Chinese public diplomacy had a prominent defensive orientation until March, as shown by the items published by the Embassy of China in Spain on its website and social media and by interviews with Chinese diplomats over the period. The Embassy’s communication efforts during the first two months of 2020 sought to prevent the stigmatisation of Spain’s Chinese community, restrictions on transport and communications with China, and criticism of the Chinese authorities for their role in the origin and spread of COVID-19.2 On the latter point, the Chinese official narrative aims to avoid an association between the consumption of the meat of wild animals without adequate sanitary controls and the origin of COVID-19, and the regime’s lack of transparency in regard to the spread of the disease.3

Once China had passed the peak of the pandemic and the latter’s epicentre moved to Europe, Chinese diplomacy became more assertive. From March, the Chinese official discourse started to emphasise China’s contribution to stop the spread of COVID-19, both through domestic measures it had adopted and through the assistance it could now provide to other countries in terms of medical material and good practices to fight against the disease. China is presented as a top scientific and medical power capable of developing and producing state-of-the-art vaccines, medicines, health protocols and medical equipment. The contrast between these defensive and assertive phases was made clear with great clarity in the two interviews with Yao Fei, Charge d’Affaires of the People’s Republic of China in Spain, in one of the most popular Spanish morning radio shows on 24 February and 17 March 2020.4 This enhanced confidence also translated into an extensive coverage from the official Chinese news agency, Xinhua, of the telephone conversation between Foreign Minister Arancha González Laya and her Chinese counterpart on March 15, in contrast with the brief news published by the EFE Press agency.

On March 21 Xi Jinping sent a message of solidarity and support to King Felipe VI similar to those sent by the Spanish authorities to China a month and a half earlier. The main difference is that President Xi offered China’s experience in ‘prevention and control, [as well as] diagnosis and treatment plans’ and used core concepts of Chinese diplomacy such as ‘mutual benefit’ and the ‘community of a shared future for mankind’. This explicit link between the fight against the coronavirus and some key concepts of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy had already been promoted by the Embassy of China in Spain, which published a statement of the Chinese Foreign Minister on its website: ‘Resolutely winning the battle against the epidemic and promoting the construction of the community of shared future for mankind’. This connection between fighting the Sars-CoV-2 and the ‘community of a shared future for mankind’ was also echoed by the Consulate General of China in Barcelona.

The public diplomacy carried out by the Chinese Consulate General in Barcelona placed a greater emphasis on the assistance provided by the Chinese community,5 in comparison with the Chinese Embassy in Madrid, which remained more focused on the official and business dimensions.6

Regarding the concerns expressed by the European External Action Service (EEAS) about Chinese disinformation on COVID-19, on 20 March the official Twitter account of the Embassy of China in Spain forwarded a message from Hua Chunying, spokeswoman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, which generated confusion about the origin and spread of COVID-19 from the US. However, beyond this instance, the Embassy of China and the Consulate General of China in Spain had not explicitly confronted the advantages of the Chinese model with those of other countries, nor explicitly discredited the EU or Spain’s traditional allies. Rather, the Chinese authorities have deployed various joint initiatives between China and those actors to combat the coronavirus.7

Spanish perceptions of China’s role in the COVID-19 crisis

Chinese assistance, cooperation and experience have been positively regarded by Spain’s Head of Government and by the King of Spain but not rated above those of other players or used to criticise the response of other countries inside or outside its borders. To date, the Spanish authorities have not changed their position, unlike the governments of other European countries –and France– by publicly requesting the Chinese authorities to provide more detailed information on the onset of COVID-19 in China.

As for the controversies over the quality of some medical supplies purchased in China, in particular rapid diagnostic tests, and the motivations of Chinese assistance to Spain, the Spanish government has adopted a conciliatory attitude. The interview given by Spain’s Foreign Minister Arancha González Laya on the CGTN programme The Point is a clear example. The Minister explained that China and Spain are countries that help each other in times of need and that ‘in exercising generosity, you [China] in a way project soft power. This is true for China as it is true for the US and for Europe’. She also acknowledged that the malfunctioning testing kits were bought through a Spanish contractor, not through direct agreements with the Chinese authorities, and that the issue had been solved with new shipments.

Likewise, although Pedro Sánchez himself said that ‘it is as important and necessary to buy abroad as it is to be self-sufficient and buy domestically’, and whereas the difficulties in purchasing healthcare equipment and materials in China’s overcrowded market have been acknowledged, there have been no publicised concerns about overdependence on China. In any case, the issue has become an internal question within the public administration and many Spanish companies, and it remains to be seen how it will be resolved in the medium term.

In Spain, the strongest criticism of the Chinese government’s management of the coronavirus crisis arose in two sectors: on the one hand, non-governmental organisations that consider COVID-19 within the context of their causes, be they press freedom, wildlife preservation or the protection of human rights protection; and, on the other, conservative and liberal politicians and media groups critical of the Spanish government that have not only condemned domestic measures in China but also China’s cooperation with Spain.8 The most critical political leaders with China are members of VOX,9 whose message echoes not only the traditional Spanish far right but also the US ‘alt-right’ with which it has significant connections, and, to a lesser extent, those of the moderate-conservative Popular Party. Senior officials of these two parties have referred to COVID-19 as the ‘damned Chinese viruses’ or ‘the Chinese plague’, have described the Chinese market as a chaotic ‘bazaar’ and have spread conspiracy theories about the origin of COVID-19.

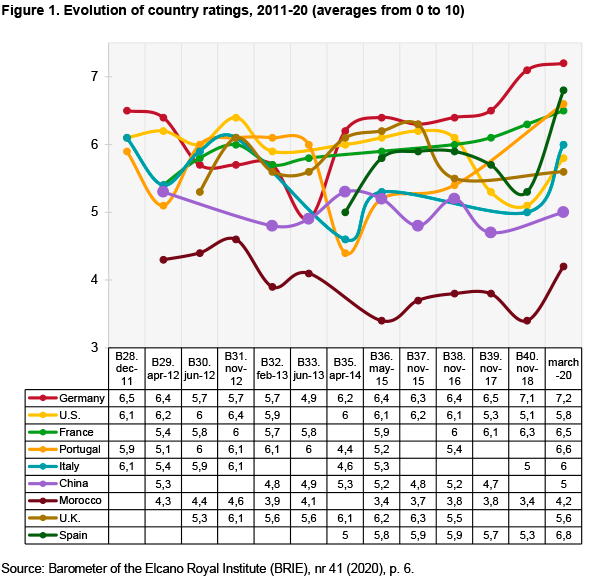

The 41st wave of the Barometer of the Elcano Royal Institute can be useful to assess how this has affected the image of China in Spain, although the collected data should be considered with caution as the study’s fieldwork was carried out on 2-19 March 2020. In other words, at the time of the survey many interviewees had not been meaningfully exposed to the events analysed in this paper. In any case, from the data in Figure 1 it could be tentatively noted that by mid-March the coronavirus crisis had neither skyrocketed or sunk the image of China in Spain. Between April 2012 and March 2020 China’s rating has ranged from 4.7 to 5.3, reaching a valuation of 5 points in March of 2020.

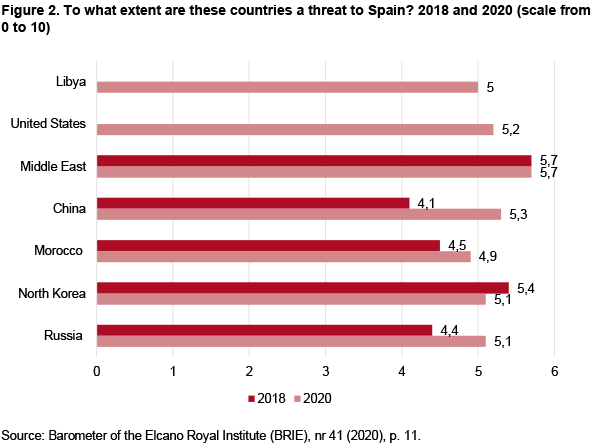

However, among the Spanish public the perception of China as a threat has indeed increased significantly (Figure 2), to the extent that China is the country whose perceived threat has increased the most since 2018 and only Middle Eastern countries were identified as the biggest threat to Spain in March 2020.

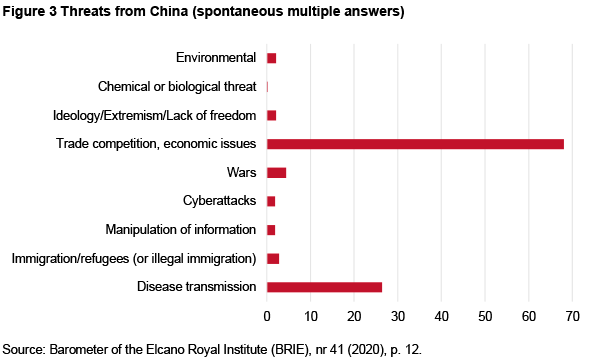

This is partly linked to COVID-19 since traditionally the perceived threat from China was exclusively associated with economic factors, while today more than 25% of Spaniards who identify China as a threat cite the diseases originating from the country (Figure 3). It is very likely that perceptions of China as a source of threat to Spain, especially with regard to disease transmission, have increased since the fieldwork of the survey was carried out: the state of emergency was not declared until 14 March and the health emergency the country was facing was not fully evident until later.

Implications for bilateral relations

Faced with the threat posed by the coronavirus, the Spanish authorities have followed a diversified foreign policy and defended multilateralism as the most effective way to deal with the crisis. This suggests they will continue to bet on maintaining close relations with China. Among other factors, the health emergency has highlighted China’s role as a provider of medical equipment and supplies to Spain and the reinforcement of multilateralism that Spain defends requires the active participation of China.10 On the latter point, it is evident that any coordinated response by the international community to face the socioeconomic crisis caused by the pandemic will be more effective if it includes the second-largest economy in the world rather than if it does not.

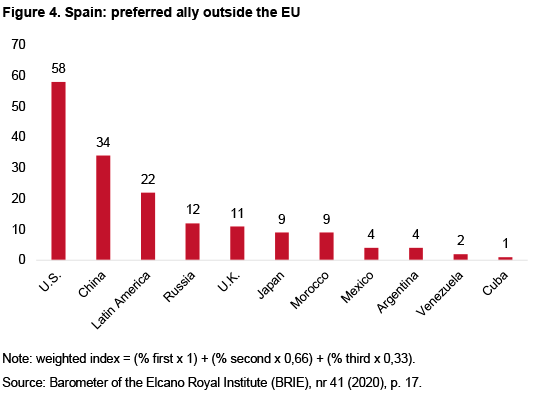

This is in line with Spanish public opinion, which identifies China as Spain’s second-preferred ally outside the EU (Figure 3).

What is not so clear, in such an uncertain context, is whether this crisis will strengthen bilateral relations in the way the Chinese government wishes. The press release by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the talks between Pedro Sánchez and Xi Jinping on 17 March 2020 stated that ‘it is believed that, following the epidemic, relations between the two countries will develop even further’. This will probably depend on three interrelated issues. The first is how the Spanish authorities assess the impact that a further rapprochement with China might have on Spain’s relations with its traditional allies. The second factor will be to what extent Spanish political authorities and companies want to depend on Chinese suppliers in such sensitive sectors as medical supplies and 5G communication networks. The third is how Spanish domestic politics evolve. Multiple statements by the leaders of the far-right VOX suggest that if they were to be part of the government the consensus on the advisability of maintaining privileged relations with China, that the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) and the Popular Party (PP) had upheld for almost four decades, could break down.11

Mario Esteban

Senior Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute and Professor at the Autonomous University of Madrid | @wizma9

Ugo Armanini

Research Assistant at the Elcano Royal Institute

1 This is a free translation by the authors of an ARI originally published in Spanish.

2 ‘Debemos trabajar juntos para combatir la epidemia’, People’s Daily, 6/IV/2020; Embassy of China in Spain, Twitter, 29/IV/2020; Khadija Bousmaha, ‘La Embajada de China critica la discriminación a su población en España: “A nuestros hijos les llaman coronavirus”’, 20 minutos, 4/IV/2020; Gu Xin, ‘Vlogger español defiende a China contra maliciosos cibernautas’, People’s Daily, 6/II/2020.

3 Between 11 February (https://twitter.com/ChinaEmbEsp/status/1227200676402470913) and 23 March 2020 (https://twitter.com/ChinaEmbEsp/status/1242043834047004672) the Embassy of China in Spain published 40 reports on the evolution of COVID-19in China on its Twitter account.

4 At that time, Yao Fei was the highest-level Chinese diplomat in Spain after the ending of Ambassador Lyu Fan’s mission in Spain. ‘Yao Fei: “En China estamos pensando en enviar equipo de médicos y expertos en coronavirus a España”’, Onda Cero, 17/III/2020; ‘Yao Fei, ministro consejero de la Embajada china en Madrid: “Algunos gobiernos han actuado de forma muy excesiva ante el coronavirus’”, Onda Cero, 24/II/2020.

5 Consulate General of China in Barcelona, Twitter, 5/IV/2020; Consulate General of China in Barcelona, Twitter, 2/IV/2020; Consulate General of China in Barcelona, Twitter, 25/II/2020; Consulate General of China in Barcelona, Twitter, 21/II/2020; Consulate General of China in Barcelona, Twitter, 14/II/2020.

6 Embassy of China in Spain, Twitter, 8/IV/2020; Embassy of China in Spain, Twitter, 7/IV/2020; Embassy of China in Spain, Twitter, 27/II/2020.

7 Embassy of the PRC in Spain, Twitter, 13/IV/2020; Embassy of the PRC in Spain, Twitter, 6/IV/2020; Embassy of the PRC in Spain, Twitter, 5/IV/2020; Embassy of the PRC in Spain, Twitter, 27/III/2020.

8 Alberto Rojas, ‘Un Chernobyl en Wuhan’, El Mundo, 9/IV/2020; David Alandete, ‘Estados Unidos pone a Sánchez como ejemplo de lo que no hay que hacer’, ABC, 9/IV/2020; Mar Llera, ‘Pekín ofrece ayuda sanitaria a España contra el coronavirus virus pero, ¿a qué precio?’, El Confidencial, 21/III/2020; Mario Noya, ‘China es culpable’, Libertad Digital, 22/III/2020.

9 VOX is a far right-wing populist party that has the third largest number of seats in the Spanish parliament.

10 Arancha González, ‘Cómo una sanidad pública global puede reactivar el multilateralismo’, Project Syndicate, 15/IV/2020; Mario Villar, ‘España cree que la respuesta al coronavirus puede marcar el futuro de la ONU’, El Heraldo de Aragon, 3/IV/2020.

11 The two parties have governed Spain alternately since 1982.

Chinese Embassy in Madrid, Spain. Photo: Luis García (CC-BY-SA-3.0-ES)