Theme

Spain has changed beyond recognition since General Franco died 40 years ago. The country telescoped its political, economic and social modernisation into a much shorter period than any other European country.

Summary

The changes in all spheres have been profound, even taking into account the prolonged recession that ended in 2014. King Juan Carlos was the engine of reforms during the transition to democracy, sealed in the 1978 Constitution. The economy, the euro zone’s fourth largest, has been fully integrated into the global economy and a bevy of multinationals created. The main black point is the very high unemployment rate. The post-Franco two-party system comprising the conservative Popular Party and the Socialist PSOE, which have alternated in power, has given Spain stability, but is now being challenged by two new parties, the centre-right Ciudadanos and the leftist Podemos. The Basque terrorist group ETA, which killed 857 people in its fight for an independent state, has been defeated by the rule of law, although it has yet to lay down its arms. The most heated issue now is the push for independence in Catalonia.

Analysis

Background1

Forty years ago this month (November 23) a granite slab weighing more than a ton and a half sealed off the embalmed body of the chief protagonist of nearly half a century of Spanish history. General Franco, ‘Caudillo by the grace of God’, as his coins proclaimed, Generalissimo of the armed forces, head of state and head of government (the latter until 1973), was buried at the colossal mausoleum partly built by political prisoners at the Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen), in the Guadarrama mountains near Madrid. José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of the Fascist-rooted Falange, which became the nucleus of Franco’s official party known as the National Movement, is buried on the other side of the altar, and mass tombs hold a small proportion (around 40,000) of the dead of both sides in the 1936-39 Civil War.

Under the guiding hand of King Juan Carlos, appointed Franco’s successor in 1969 when the dictator decided to re-instate the Bourbon monarchy, opponents and moderate elements in the regime came together and negotiated a transition to democracy, sealed in the 1978 Constitution.

Consensus, after so polarised a past, was very much the watchword between the reformist right and the non-violent left. This was epitomised by the Pacto de Olvido (literally, Pact of Forgetting), an unspoken agreement to look ahead and not rake over the past for political reasons. None of the parties had any interest in having the role they played during the Second Republic and the Civil War put under the microscope. The pact was institutionalised by the 1977 Amnesty Law; there was no Chilean-style truth and reconciliation commission.

Spain joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1986 and NATO in 1982 (ratified in a referendum in 1986) and was a founding member of the euro zone in 1999, all of which enabled the country to integrate itself into the world at large after a long period of relative isolation.

According to a survey in 1975, 75% of respondents wanted press freedom, 71% religious freedom (Roman Catholicism was the state religion) and 58% trade-union freedom. The country was ripe for change. Laureano López Rodo, the chief architect of a series of development plans in the late 1960s that began to move the economy away from autarky and towards liberalisation, had rather prophetically said at that time, ‘We shall start thinking about democracy when income per head of the population exceeds US$1,000’. Per capita income crossed the US$500 line in 1963 and US$1,000 in 1971, four years before Franco died. A middle class had been created.

An unprecedented period of modernisation

Over the last 40 years Spain has enjoyed an unprecedented period of prosperity and peaceful co-existence, even taking into account the prolonged recession that ended in 2014. The changes have been profound; the country telescoped its political, economic and social modernisation into a much shorter period than any other European country (see the Appendix):

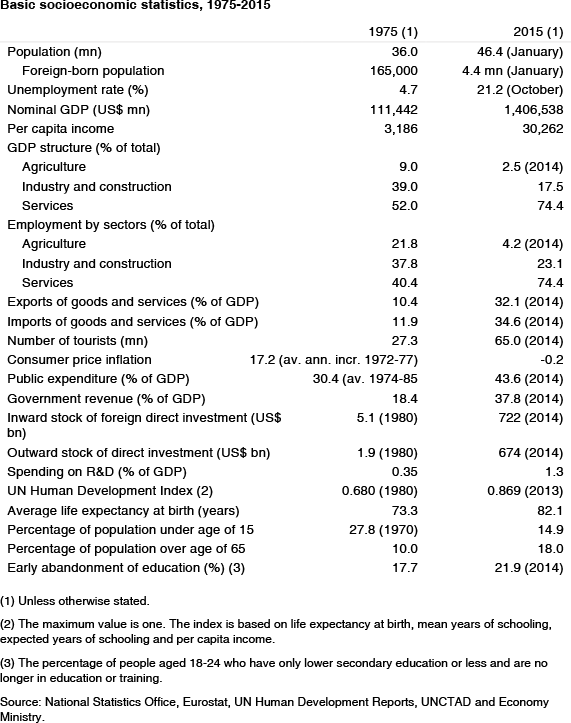

- Economic output increased almost tenfold between 1975 and 2015 to around US$1 trillion.

- Per capita income rose from US$3,000 to more than US$30,000.

- The structure of the economy is very different: agriculture’s share of output dropped from 9% to 2.5%; industry, including construction, from 39% to 23% and services increased from 52% to 74%.

- Employment by sectors has changed even more: only 4% of jobs today are in agriculture compared with 22% in 1975, 14% of employment is in industry and construction, down from 38%, while services employ 76%.

- Exports of goods and services more than trebled to 32% of GDP.

- The inward stock of foreign direct investment in Spain surged from US$5.1 billion in 1980 (the earliest recorded figure) to US$722 billion in 2014.

- The outward stock of direct investment jumped from US$1.9 billion to US$674 billion, with the creation of well-known multinationals.

- The number of tourists rose from 27 million to an estimated 68 million this year.

- There were 123 cars per 1,000 people in 1975 and more than 500 today.

- The population rose by 10.4 million to 46.4 million, mostly over a 10-year period as a result of an unprecedented influx of immigrants. In the decade before the 2008-13 crisis Spain received more immigrants proportional to its population than any other EU country.

- Average life expectancy for men and women was 73.3 years in 1975; today it is 82 years. Spanish women live 85 years, almost the longest in the world.

- Close to 30% of the population was under the age of 15 in 1975; today it is 15%. Those over the age of 65 rose from 10% to more than 18%.

- The average number of children per woman has more than halved to 1.3, one of the world’s lowest fertility rates.

Spain also became one of the world’s most socially progressive countries, a far cry from the rigid and asphyxiating morality of the Franco regime and the strictures of the powerful Roman Catholic Church. In 2005 Spain legalised marriage between same-sex couples. Only three other countries at that time had taken this step –the Netherlands, Belgium and Canada. Fast-track divorces were also introduced that year under which couples no longer had to be separated for a year prior to legal proceedings and there was no requirement to attribute responsibility for the failure of the marriage. Divorce was not legalised until 1981; before then a marriage could be dissolved only through the arduous procedure of ecclesiastical annulment, which was available only after a lengthy series of administrative steps and was thus accessible only to the relatively wealthy.

In a country whose exaggerated respect for masculine values added the word machismo to the English language, women’s position in society has advanced considerably. During the Franco regime a married woman, for example, could not apply for a passport or sign a contract without her husband’s permission.

Women today account for 46% of the working population, up from 30% in 1975. Female university students outnumber male graduates and hold 40% of the seats in parliament. Society is also increasingly secular and less influenced by the Roman Catholic Church, a pillar of the Franco regime until its last years.

In the Basque Country, the terrorist group ETA, which murdered 857 people in its fight for an independent state (95% of them since 1975), has been defeated by the rule of law. The group declared a ‘definitive’ ceasefire four years ago, although it has yet to lay down its arms.

The main black point as regards the economy is the unemployment rate: up from a mere 5% in 1975 to a whopping 22% today, although that low level at the end of the Franco regime was artificial as the economy was protected from the chill winds of competition, and could not have sustained that situation for much longer.

Companies with leading positions in the global market

Few if any Spanish companies were known outside of Spain in 1975, except, perhaps, for Iberia, the flagship airline, and the Real Madrid football club. Indeed, corporate Spain had made little mark on the outside world. Today, there are at least 20 companies with significant positions in the global economy. Santander is the largest bank by market capitalisation in the euro zone and the leader in Latin America, Iberdola is the world’s main wind-farm operator, Inditex, best known for its Zara brand, is the world’s top fashion retailer by sales and ACS/Hochtief is the leading developer and manager of transport infrastructure.

Spain, along with South Korea and Taiwan, has produced the largest number of global multinationals among the countries that in the 1960s had not yet developed a solid industrial base.

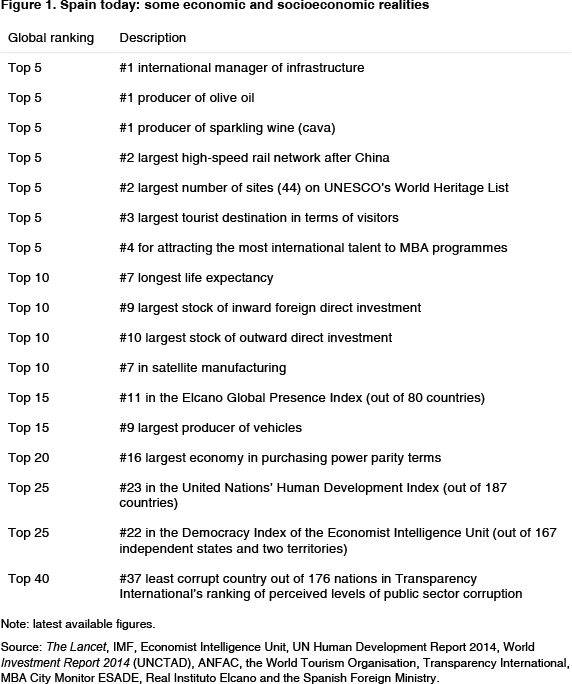

Spain has also attained leading positions in areas such as solar energy, high-speed rail network and MBAS programmes (see Figure 1).

From economic miracle to crisis

Spain’s rapid economic progress was almost too true to be believed, and it came to an end in 2008, following the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the US and the collapse of Lehman Brothers, which almost brought down the world’s financial system and led to a credit crunch. The more than decade-long period of what Spaniards called las vacas gordas (fat cows) was mainly fuelled by the labour-intensive, debt-fuelled and oversized construction and property sectors. The number of housing starts in 2006 was 865,000 –more than Germany, France and the UK combined–. Such frenetic building was only made possible by the influx of immigrants (3.6 million between 2000 and 2007) and created a lopsided economy. The housing stock increased by 5.7 million during the boom, the equivalent of almost 30% of the existing stock. The impact on employment was dramatic: between 1995 and 2007 eight million jobs were created.

The economy was going so well that José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the Socialist Prime Minister between 2004 and 2011, adopted a football metaphor and proclaimed in September 2007 that Spain ‘has joined the Champions’ League’. That same year he also called Spain’s economic model ‘an international model of solvency and efficiency’. The truth is that Spain’s boom was a false bonanza as it was built on unsustainable foundations.

Jobs were shed almost as quickly as they had been created during the boom. The jobless rate more than trebled to a peak of 27% in 2013. Due to much lower firing costs, the first people to lose their job were those on temporary contracts, particularly males, in the construction sector, many of whom had left school at 16. Nowhere was this more rife than in Villacañas, which became the door-making capital of Spain. At the height of the boom, this town of 10,000 inhabitants had 10 door manufacturing plants employing 6,000 people and producing 11 million doors a year, 60% of the national total. Hardly anyone stayed on at school. One bright lad saw the writing on the wall and stopped working in one of the factories so he could complete his education. He did so well that he won a place at the London School of Economics and went on to work for the Bank of Spain.

The early school-leaving rate peaked at 31% in 2009, more than double the EU average. It was down to 22% last year, still very high, as students had no option but to continue their education. These unqualified workers form a ‘lost generation’.

The European Central Bank’s one-size-fits-all monetary policy produced asymmetric effects. The policy was too loose for Spain and led to negative real interest rates. This distorted rational behaviour of economic agents and promoted excessive indebtedness, the accumulation of imbalances (the current account deficit hit close to 10% of GDP in 2007) and significant competitiveness losses. At one stage Spain accounted for one quarter of the euro zone’s total lending and also for around one quarter of the total number of €500 notes in circulation in the then 12 euro zone countries –much higher than what corresponded to the country’s economic size (10%)–.

Savings banks, in particular, were hard hit as they were saddled with unpaid mortgages from people who had lost their jobs and real estate developers that went bust. Some of them had to be bailed out by the EU.

Political factors were also very much at the root of Spain’s crisis, particularly the degeneration of key institutions (the judiciary, regulatory bodies, the Court of Auditors, etc) that were colonised (along with the savings banks) mainly by the two largest parties, the Popular Party and the Socialist PSOE, and consequently failed to fulfil their accountability role. In the process, these institutions were discredited and lost legitimacy and the political class was perceived as an extractive elite. An effective system of checks and balances would have gone a long way towards reducing the scale of crony capitalism and hence the crisis.

Corruption flourished, particularly in the interface between politicians and the construction sector. Spain, however, never sank to the level of Italy (ranked 69th out of 175 countries in the latest corruption perception index by the Berlin-based Transparency International, compared with Spain’s 37th position). Even the monarchy was tarnished. King Felipe’s sister the Infanta Cristina was indicted as part of a four-year probe into her husband, Iñaki Urdangarín, who faces charges of money-laundering, fraud and embezzlement through a non-profit foundation he set up. They will stand trial in January.

From crisis to recovery

Spain is now out of a long recession and is growing at one of the fastest rates in the EU, but from a low base as it has yet to recover the pre-crisis level of economic output. Jobs are being created, albeit mainly precarious ones, partly thanks to the 2012 labour-market reforms, exports continue to steam ahead and the tourism sector is enjoying another bumper year. Yet the unemployment rate is still more than 20%.

In the German government’s eyes, Spain is something of a poster boy for the benefits of orthodox austerity measures, which it certainly is compared with basket-case countries like Greece. Pensions have been cut, social expenditure reduced, public sector wages frozen and income taxes and VAT increased. German Chancellor Angela Merkel hailed Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy as ‘the prime minister of one million jobs’ at the European People’s Party congress in Madrid last month.

The budget deficit is finally heading towards the EU threshold of 3% of GDP next year, compared with 10.3% in 2012, although the European Commission recently asked Spain to re-do its numbers as it thought they were too optimistic. The size of the public debt, however, has ballooned to 100% of GDP, three times the level in 2007. This is an albatross around Spain’s neck.

Breaking the mould of post-Franco politics

Not surprisingly, massive unemployment, austerity and corruption are impacting politics. Two new upstart parties at the national level, the centre-right Ciudadanos (Citizens) and the anti-austerity leftist Podemos (We Can) are challenging the conservative Popular Party and the Socialists, the two parties that have alternated in power since 1982. For the first time since then, the general election on 20 December will be a four-horse race, and the opinion polls show none of them will win an absolute majority. Spain is one of the very few countries in the EU not to have had a coalition government in the last 40 years. This is an important challenge.

Podemos, born out of the month-long occupation in May 2011 by thousands of mainly young people of the Puerta del Sol square in the heart of Madrid, became a political party in January 2014. In last May’s municipal elections Podemos and its allies took control of the Madrid and Barcelona town halls. Its founders come from the faculty of political science at Madrid’s Complutense University, well known for its long-standing commitment to far-left ideology. Pablo Iglesias, the 36-year-old pony-tailed leader of Podemos still lives in a modest flat in Vallecas, one of Madrid’s poorest areas, in a graffiti-daubed 1980s estate of apartment blocks. ‘Defend your happiness, organise your rage’, reads one graffiti slogan.

Podemos was riding high in the voter intention polls until January of this year when its share of the votes peaked at 28%, ahead of the Popular Party and the Socialists, and last month it was down to 14%. The party and its allies did badly in September’s election in Catalonia, billed as a referendum for independence, winning only 9% of the vote. In an unconvincing U-turn, Podemos began to pitch itself earlier this year as a Nordic-style social-democrat party. The party seems to be trying to be all things to all men.

Ciudadanos, on the other hand, is on a roll. Its support has risen (from 8% in January to 21%) almost as much as Podemos’s has declined, and it will probably be the kingmaker, getting into bed with either the Popular Party or the Socialists in a coalition government, depending on which one gets the most votes. The Popular Party is betting on voters returning it to office because of the turnaround in the economy –the number of unemployed has dropped below 5 million for the first time since 2011–.

The market-friendly Ciudadanos, led by the 35-year-old Albert Rivera, started life in Catalonia eight years ago. Few outside of the region had heard of the party. It began to be better known after campaigning for a ‘no’ vote in the non-binding referendum on independence held a year ago in defiance of a ban by the Constitutional Court. In last September’s Catalan election, Ciudadanos won 18% of the vote, double the share of Podemos and making it the second-largest party in the region, ahead of both the Popular Party and the Socialists.

Rivera says the difference between his party and Podemos is that whereas Ciudadanos wants justice, Podemos wants revenge. The latter’s short-lived rise was something of a paradox. Spain’s ideological self-placement scale has changed little over the last 20 years, rarely dropping below 4.5 where 5.0 is the centre (with 0 being extreme left and 10 extreme right).

Spaniards do not want a rupture with the recent past (just as they did not when Franco died), with what a Podemos ideologue calls the ‘regime of 1978’ in reference to the democratic constitution of that year. What Spaniards want is for the system to work fairly and equally, without privileges and impunity for the political class.

The monarchy has served Spain well. It has been tarnished by the corruption scandal in the royal family and is under scrutiny. But the institution –and it is to be hoped the country as whole– is demonstrating a capacity to regenerate itself. The least of Spain’s problems is whether to revert to a republic, or keep the monarchy. A Socialist or a Popular Party President would not be above the political fray in partisan Spain as much as King Juan Carlos I was or his son Felipe VI (Juan Carlos wisely abdicated in his favour last year) is proving to be. Felipe has not put a foot wrong in his first year on the throne and enjoys high approval ratings –far higher than those of any other public figure–.

The challenges ahead

The most heated problem facing Spain is the issue of Catalan independence. The parties campaigning for independence, an unholy alliance of conservative nationalists, radical republicans and anti-capitalists, won 48% of the vote in September’s election and 53% of the seats in the regional parliament. This is hardly a clear mandate to move towards a separate state, as the Catalan parliament has announced it will do.

Franco would have solved the problem, not that it could have risen in his very centralised dictatorship, by sending in the tanks. The central government is using some of the democratic weapons it has at its disposal to rein in the independence movement, such as summoning Artur Mas, the Prime Minister of Catalonia, to testify in court for holding a symbolic non-binding referendum in 2014 on the issue of a separate state in defiance of the Constitutional Court.

There is no knowing how this saga will end; whatever solution there is will not come until after the December general election and could result in reforms to the constitution. Spaniards desire the kind of consensus that existed during the transition years.

In the economic sphere, Spain has yet to rebalance its productive model and make it more knowledge-based and sustainable and less reliant on the construction sector. There are two constraints here: construction is labour-intensive, and Spain urgently requires jobs, and the education system needs to be greatly improved.

The other problem is the sustainability of the social security system, despite pension reforms which are gradually extending the retirement age from 65 to 67, increasing the number of years required to qualify for the maximum pension and no longer automatically indexing rises to annual inflation. Social security spending, swelled by unemployment benefits, during this government has exceeded revenues (depleted by the massive number of jobless) by more than 3% of GDP. Pensions have been paid by raiding the reserve fund created in 2000 and built up during the boom years. The reserve rose from €35.8 billion in 2006 to a peak of €66.8 billion in 2011 and then fell to €39.5 billion in June 2015 (3.7% of GDP). If this pace of drawing down the reserve were to continue and no measures taken, it would run out in 2019.

Franco famously said that he had left his regime and its institutions ‘tied up, and well tied up’. The knots were unravelled successfully and peacefully. One, however, has proved to be very difficult and sensitive, and that is how to openly confront Spain’s recent past, unlike, most notably and admirably, Germany. Perhaps the wounds caused by a civil war, and with the victors rubbing their triumph into the noses of the losers during the Franco regime, are the most difficult to heal and so, this argument goes, better left as they are.

There is still no consensus on what to do with the contentious Valley of the Fallen monument, which in no way can be called a site of reconciliation. The failure to agree on how to confront the past makes it difficult to find an accord over an uncertain future.

William Chislett

Associate Analyst, Elcano Royal Institute | @WilliamChislet3

Appendix

1 William Chislett covered Spain’s transition to democracy for The Times between 1975 and 1978. He is the author of Spain: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press). The Real Instituto Elcano will publish his new book on Spain in early 2016.