Theme

Counter-narcotics cooperation between Spain and the US is of growing importance to both countries but remains limited in scope.

Summary

Flows of illicit drugs transiting the Atlantic into Spain from the Americas are of growing concern to Spain and the US with law enforcement, judicial, military and intelligence agencies intensifying cooperation in an effort to disrupt the global distribution of illicit drugs. This cooperation is described by various Spanish and US officials as ‘excellent’, ‘fluid’ and ‘successful’. At present, the primary focus of cooperation involves interdiction efforts between the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and the Spanish National Police, Guardia Civil and Customs agency. Effective judicial cooperation leading to successful prosecutions of traffickers, while important, is hampered, at times, by differing judicial systems. Judicial cooperation should be intensified to more effectively prosecute traffickers and dismantle criminal networks. Defence cooperation and the role of the US military in counter-narcotics efforts is limited in scope and mostly takes place in the context of multilateral efforts.

Analysis

Narcotics trafficking from the Americas to Spain

Spain has for several years been one of the most important southern entry points for cocaine and other drugs entering Europe and cultivated and processed in Latin America. The flow of illicit drugs into Spain is not only destined to the broader European market1 but also supplies a significant Spanish market for cocaine and other drugs such as methamphetamine. According to data from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Spain has one of the highest rates of cocaine use in the world, falling behind only the UK and Albania. According to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) Drug Markets Report, seizures of illicit drugs in Spain are the highest among EU states.2

The routes used by traffickers to enter Spain have varied over time. In 2006 and 2007 cocaine was entering via transatlantic routes through Western Africa. The drugs, principally cocaine, originated in the Andean region of South America and were smuggled into Venezuela and Brazil, then shipped across the Atlantic into the Western Sahel region of Africa. The Bight of Benin, between Ghana and Nigeria, as well as Senegal and Guinea Bissau, were the main transit points. From there the narcotics were smuggled northwards through the Maghreb region of North-West Africa, across the Mediterranean and into Spain.3

While there is evidence of shifting trends and declining importance of the Africa trafficking routes, these should not be discounted entirely. The use of West Africa as a transit route could increase again if interdiction efforts in the Caribbean force traffickers to shift international drug smuggling patterns.4

The persistence of weak governance capacity and high corruption levels continue to make West Africa an attractive option for trafficking. According to the 2017 United Nations World Drug Report, the decline in cocaine intercepted in Africa in recent years may be the result of ‘poor capacity of detection and reporting rather than a decrease in the flow of cocaine’. The 2018 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) likewise states that Guinea-Bissau’s ‘weak law enforcement capabilities, corruption, porous borders and convenient location make it susceptible to drug trafficking’. While these countries are not a significant source of illicit drugs, they continue to be a significant transit zone for drug trafficking from South America to Europe.5

Furthermore, the existence of state and non-state actors in West Africa that have developed well-established trafficking routes also suggest the region will continue to be an attractive alternative for traffickers. In some cases, terrorist groups such as Boko Haram and al-Shibab have specialised in smuggling illicit drugs into Europe via West and North Africa using both air couriers and vehicles. It is assumed that the involvement of violent extremist organizations (VEO) in the drug trafficking business is intended as a source of financing for other terrorist activities.

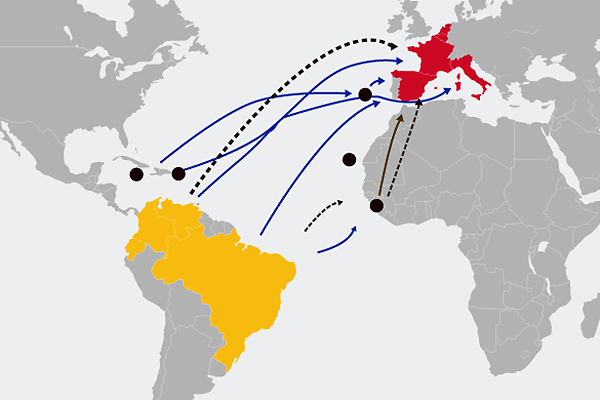

Nevertheless, despite the continued importance of African trafficking routes, several recent reports and data suggest the Caribbean has become the principal trafficking route for cocaine destined for Spain and Europe. Figure 16 below illustrates the variety of routes traffickers use to bring illegal narcotics into Spain and Europe.

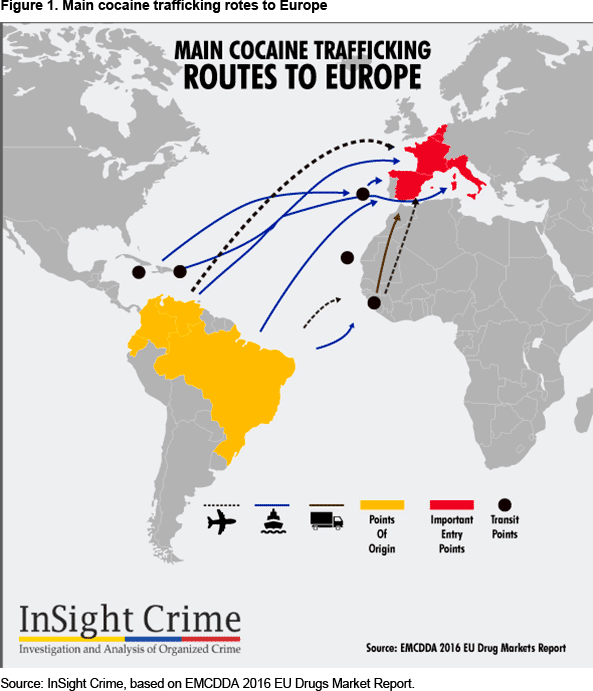

The 2016 EMCDDA report further highlights the importance of Caribbean maritime routes. It notes the relatively porous border between Colombia and Venezuela and the ease with which cocaine can be transported on ‘go fast’ boats between Venezuela and Caribbean island nations, particularly Jamaica and the Dominican Republic.

A recent study by InSight Crime suggests there may be multiple reasons for the shift to Caribbean routes.7 Venezuela’s economic collapse means that there are fewer commercial flights and less commercial shipping between Venezuela and Europe or Africa. As a result, the island nations of the Eastern Caribbean offer a convenient alternative because of their geographic proximity. Furthermore, the Dominican Republic, and to a lesser extent Jamaica, offer a convenient stopover for drugs because of the high volume of tourists, which contribute to local demand, and the well-developed tourist infrastructure that attracts travellers from the US and Europe, including Spain. Furthermore, both the Dominican Republic and Jamaica have well-established criminal networks with significant trafficking expertise built up over time. Figure 2 shows these newer routes.8

It should be noted, however, that the bulk of cocaine (on average 90%) is destined for the US and is entering the US market via the Central American and Mexico corridor. Nevertheless, the dramatic increase in the cocaine supply in Colombia has resulted in the Caribbean becoming an important, albeit lesser, route. In this context, the Dominican Republic in particular has become an important hub for cocaine heading for Europe.

Operational success based on law-enforcement cooperation

Given the importance of Spain as a consumer market for illicit drugs, and its importance as a supply route feeding the broader European market, the urgency of counter-narcotics cooperation between Spain and the US has increased in recent years. Over the past five years the US government, as well as the Spanish and international press, have reported numerous cases of successful narcotics interdiction that have resulted from stepped-up US-Spain counter-narcotics cooperation.

This cooperation has led to numerous important seizures of illicit drugs –primarily cocaine– and is the by-product of ‘fluid communication and collaboration’ between both countries, according to one Spanish official. The US Department of State has characterised bilateral cooperation with Spain similarly stating that it maintains ‘excellent bilateral and multilateral law enforcement cooperation (with Spain)’9 in the annual International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR).

Because of Spain’s importance as a consumer market and transit point into Europe for cocaine originating from South America, Spanish law enforcement agencies have played a critical role in interdiction efforts. According to the INCSR and numerous press accounts, the Cuerpo Nacional de Policía de España and the Guardia Civil have implemented several effective strategies to interdict drugs before they enter Spain and the rest of Europe. These strategies included ‘strong border control and coastal monitoring, sophisticated geospatial detection technology, domestic police action, anti-corruption and internal affairs investigations, and international cooperation’ in 2017.10

The following table highlights some of the recent successes in U.S.-Spain law enforcement cooperation including arrests and seizures, combining data from INCSR reports as well as international news sources.Figure 3. Recent reported successes for US-Spain counter-narcotics cooperation

| Date | Arrest/seizures | Joint-cooperation description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| November 2017 | 40 people arrested and nearly 4 tons of cocaine seized | Long-term anti-drug cooperation between the Cuerpo Nacional de Policía de España, along with Moroccan domestic intelligence and intelligence cooperation with the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and German and Italian security services | North Africa Post |

| October 2017 | 3.7 tons of cocaine seized from a vessel in the Atlantic | Joint-cooperation between the Aduana Española and the Cuerpo Nacional de Policía de España in conjunction with the US DEA and UK National Crime Agency (NCA) under the overall coordination of the Maritime Analysis and Operations Centre-Narcotics (MAOC-N) | BBC |

| July 2017 | Spanish citizen entering Spain arrested for carrying 600 grams of cocaine | Cooperation between the Aduana Española and US Homeland Security | INCSR |

| May 2017 | Seven crew members in the Atlantic Ocean on board a ship under the Venezuelan flag arrested and more than 2 tons of cocaine (2400 kg) seized | Operation of the Cuerpo Nacional de Policía de España along with intelligence cooperation with the US DEA, UK National Crime Agency (NCA) and the Portuguese Police | Reuters, Business Insider |

| April-September 2017 | 950 kg of cocaine and over €10 million in bulk cash seized, destined for a cocaine supplier in South America | Joint operation of the Spanish authorities with the US Drug Enforcement Administration and US Immigration and Customs Enforcement | INCSR |

| February 2017 | 24 members of a Colombian drug trafficking organisation operating in Spain arrested and 2.45 tons of cocaine seized | Cooperation with the Cuerpo Nacional de Policía de España and the US DEA | INCSR |

| January 2016 | Vehicle in Southern Spain intercepted, leading to the seizure of 3 tons of cocaine | Joint-Cooperation between the Cuerpo Nacional de Policía de España along with the US DEA and the UK NCA | United Press International |

Source: US State Department 2017 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) and various news sources such as North Africa Post, Reuters, United Press International and the BBC.

The mechanics of law-enforcement cooperation

As these examples suggest, cooperation has been primarily law-enforcement based –between the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and three Spanish law enforcement agencies: the Policía Nacional, the Guardia Civil and the Aduana Española. Many of the reported joint interdiction cases are based on intelligence information developed by US sources and brought to the attention of Spanish officials by DEA liaison officers stationed at the US Embassy in Madrid. Other cases are the result of intelligence gathered and analysed at fusion centres in Florida or Portugal.

It is noteworthy that there is no formal agreement and no formal Memorandum of Understanding to define or guide current counter-narcotics cooperation between the two countries. Instead, cooperation occurs in the context of existing accords such as extradition agreements and international conventions to combat illicit drugs and is often based on case-by-case requests that result from specific intelligence brought to the attention of law-enforcement authorities.

The kind of US counter-narcotics assistance overseen by the Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL), and typical in US-Latin American cooperation, is inexistent in US-Spain counter-narcotics efforts. INL works in more than 90 countries to counter crime, illegal drugs and instability. Nevertheless, Spain is among a list of nations that are precluded from receiving INL assistance because they are deemed sufficiently developed and possess adequate institutional capacity, rendering unnecessary the kinds of institutional strengthening INL normally provides.

Intelligence fusion centres

An important element of US and Spanish counter-narcotics cooperation is the two fusion centres where intelligence is gathered, analysed and shared between the US military and representatives from multiple US government agencies, as well as foreign countries.

For the US, the most important of these is the Joint Inter-Agency Task Force-South (JIATF-South), an intelligence fusion centre and part of the US military’s Southern Command. Based at the Naval Air Station in Key West in the state of Florida, JIATF-South’s mission is to conduct ‘detection and monitoring (D&M) operations throughout their Joint Operating Area to facilitate the interdiction of illicit trafficking in support of national and partner nation security’.11

As a fusion centre, its primary purpose is to gather, analyse and produce actionable intelligence for the US and partner nations. For instance, JIATF-South gathers real-time radar and intelligence information to track an average of 1,000 targets a day. It also provides a space for coordination (or fusion) between the US military and multiple civilian law enforcement and intelligence agencies such as the Justice Department (DOJ), DEA, FBI, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and its Customs and Border Protection (CBP). Additionally, it has a multilateral function in which Country Liaison Officers (CLOs) from 13 other countries, including Spain, are stationed there.12

In addition to detecting and monitoring targets, JIATF-South will also ‘find and deploy assets’ to interdict the targets. One such operation, with the code-name Martillo, is a multinational effort employing military and law-enforcement units from 14 participating countries, including Spain, in an effort to ‘deny transnational criminal organisations the ability to exploit these trans-shipment routes for the movement of narcotics, precursor chemicals, bulk cash and weapons along Central American shipping routes’. As the description suggests, JIATF-South’s priority is to stop the flow of drugs into the US. Nevertheless, the increasing use of Caribbean routes and the importance of the Dominican Republic as a transfer point to Spain suggests that the fusion centre also tracks transatlantic trafficking. Since its inception in January 2012, Operación Martillo has resulted in the seizure of 693 metric tonnes of cocaine, US$25 million in bulk cash, 581 vessels and aircraft detained and the arrest of 1,863 suspects.13

A second fusion centre is the Europe-based Maritime Analysis and Operation Centre-Narcotics, known by its acronym MAOC-N. With its headquarters in Lisbon, its operations are very similar to those of JIATF-South. MAOC-N member states include Spain, the UK, Ireland, France, the Netherlands, Italy and the host country, Portugal. The agency is co-funded by the EU’s Internal Security Fund and serves as a base for multi-lateral cooperation to combat illicit drug trafficking both by sea and air, with the aim of intercepting shipments before they arrive in West Africa and Europe. MAOC-N coordinates multi-lateral criminal intelligence and information exchanges between the partner countries to support police action with naval and law-enforcement agencies.

Like JIATF-South, MAOC-N is staffed by Country Liaison Officers (CLOs) including police, customs, military and maritime authorities from its member states. Though the US does not have a CLO at the MAOC-N, a permanent US observer from the DEA is stationed at the centre. There are also several additional observing parties at MAOC-N, including the European Commission, EUROPOL, UNODC, EMCDDA, the European External Action Service (EEAS), the European Defence Agency (EDA), EUROJUST and FRONTEX.

The centre has conducted several successful operations since its launch in 2007, having ‘supported the coordination and seizure of over 116 tons of cocaine and over 300 tons of cannabis’ between its inception and 2016.14

Judicial cooperation and prosecutorial challenges

While Figure 3 above offers a partial catalogue of successful law-enforcement counter-narcotics cooperation between the US and Spain, the successes are primarily operational in nature and, at times, do not result in judicial prosecutions. As a result, bilateral counter-narcotics operations have led to the seizure and removal of illicit drugs from the supply chain, as well as many arrests, but have not always generated the successful prosecution of traffickers and criminal networks.

Both governments favour prosecutions and, in fact, some important successes have occurred. For example, in a sentence handed down by the Tribunal Supremo, Sala de lo Penal, in February 2016, the court recognised the role of the DEA and established a limited principle that foreign police forces cannot be held to Spanish legal standards. An excerpt from the Court’s decision follows:

‘En el ámbito de la cooperación penal internacional en el que se juega el enfrentamiento contra los graves riesgos generados por la criminalidad organizada trasnacional, y en el que nuestro país tiene asumidas notorias obligaciones adaptadas a un mundo en el que la criminalidad está globalizada (Convención de las Naciones Unidas de 1988 sobre estupefacientes, entre otras), no pueden imponerse las reglas propias determinadas por problemas legislativos internos a los servicios policiales internacionales, por lo que ha de respetarse el ordenamiento de cada país, siempre que a su vez respete las reglas mínimas establecidas por los Tratados de Roma o Nueva York. De la misma manera que no es posible ni exigible imponer a otros sistemas judiciales la autorización judicial de las escuchas, tampoco lo es imponer a otros servicios policiales las mismas normas que la doctrina jurisprudencial ha establecido para los servicios policiales españoles.’15

Nevertheless, judicial cooperation in counter-narcotics efforts will require further deepening to ensure greater effectiveness.

Differences in judicial cultures, norms and practices has been a primary challenge in effective judicial cooperation. This is not surprising since judicial practices such as the rules of evidence and norms for establishing case facts vary from country to country based on the legal history and practices developed in a particular country over time. Furthermore, the commonly used practice of using confidential informants in the US is less well accepted in Spain, which can contribute to difficulties in effective prosecution. These experiences are not dissimilar to those of US-Mexico judicial cooperation, so it should be no surprise that Spanish and US law enforcement and legal systems experience similar challenges.

A recent decision handed down by the Tribunal Supremo de España provides some insight into the challenges both countries experience in effective judicial cooperation. According to the Tribunal’s finding from 12 March 2018, the US DEA conducted covert operations to track a small fishing vessel on the high seas it believed to contain between 300 to 500 kilos of cocaine hidden in its interior. Intelligence on the shipment suggested that its intended destination was Spain and that its organiser was Luis Alberto Moreno Ruiz, a Colombian citizen and legal resident of Spain. Moreno was known to act as an intermediary between Colombian cocaine suppliers and buyers in Spain and throughout Europe. Using phone records, the court record shows that the DEA tracked down Luis Henry Restrepo Morales, who would be coordinating the delivery arriving in Spain.

Based on court documents, it appears that the DEA seized the Boston Whaler, a smaller fishing boat inside the catamaran, with support from the US Coast Guard and subsequently transferred it to the US territory of Puerto Rico. The Boston Whaler, with cocaine allegedly hidden in its hull, remained in a warehouse in Puerto Rico for nearly a month between June and July 2014. At the end of that time, the boat, with cocaine still on board, was transported to Spain on a USAF plane, where it entered the custody of the Policía Nacional de España. At this point, the boat’s hull was broken open, revealing 240kg of cocaine.

In the original lower court ruling of 17 May 2017, the National court ruled that the defendants –Luis Henry Restrepo Morales, Julián del Prado Montero, Gloria Efigenia Echeverry Mesa, Yaneth Betancur Gómez and Juan Carlos Dámaso Halfhide– were not guilty (given a sentencia absolutoria) because there was no way of determining with full certainty that the boat sent by the US Coast Guard to Spain in July 2014 was the same as that seized on the high seas by the DEA the month before. A year after the National Court’s decision, the public prosecutor (ministerio fiscal) appealed the case in March 2018 to the Tribunal Supremo de España on the following grounds:

‘Esta sala ha visto el recurso de casación num. 1496/17 interpuesto por el Ministerio Fiscal, por infracción de ley e infracción de precepto constitucional, contra la sentencia absolutoria dictada por la Audiencia Nacional (Sección Tercera) en fecha 17 de mayo de 2017, en causa seguida por delito de tráfico de drogas’… ‘Sostiene el Fiscal que la conclusión recogida en este último párrafo del relato de hechos probados se sustenta en una motivación arbitraria e irrazonable, y como tal vulneradora del artículo 24.1 CE.’16

Nevertheless, the defendants offered a statement from Sr Rebullido Lorenzo, a Spanish naval engineer, maintaining that the DEA would not have been able to intercept a boat on the high seas with that amount of cocaine loaded inside it without a significant number of people, docking it or using a crane to raise it. Sr Rebullido’s statements created doubt in the veracity of the sequence of events and chain of custody while the boat was held by the DEA. Based on the naval engineer’s statement and evidence from the original ruling, the Tribunal Supremo de España dismissed the public prosecutor’s appeal, siding with the National Court and upholding the original not guilty ruling. Though a significant amount of cocaine was seized, no one was convicted in this case.

Fortunately, the kinds of challenges in judicial procedures, such as those related to chain-of-custody issues, can be overcome when judicial cooperation is central to overall law-enforcement efforts from the outset. Integrating judicial and prosecutorial aspects into counter-narcotics operations can ensure that seizures and interdiction efforts have a longer-term impact through effective prosecutions of traffickers. This has certainly been the case between Mexico and the US, where effective judicial cooperation has deepened and law-enforcement agencies in both countries are increasingly aware of the judicial standards in the other country. There is no reason to doubt that Spain and the US can achieve this type of effective cooperation over time but it will require building greater trust to ensure that effective prosecutions and the dismantling of criminal networks are the result. This process can begin by making the most of specialised units within the Spanish Prosecutor’s Office, such as the Spanish Antidrug Prosecution unit and inter-regional stakeholders such as the Ibero-American Network of Antidrug Prosecutors.

Another step in building greater trust is in the presence of a judicial liaison officer (magistrado de enlace judicial) stationed at the Embassy of Spain in Washington DC. The scope of this position is much broader than counter-narcotics cooperation and includes issues related to common crime, extradition and terrorism. Given the variety and complexity of judicial issues between both nations, one simple recommendation might be to increase the number of liaison officers assigned to each capital and include a specialised judicial officer focused specifically on counter-narcotics cases.

Broader US-EU cooperation

Finally, it should be noted that US-Spain counter-narcotics cooperation also takes place in the broader multilateral setting, especially in the context of US-EU cooperation. UNODC implemented a project on law-enforcement and intelligence cooperation against cocaine trafficking from Latin America to West Africa and into Europe. The programme is supported by the European Commission and has facilitated the signing of several bilateral agreements to encourage joint investigations and the timely exchange of operational information between law-enforcement agencies to promote intelligence-led investigations for intercepting drugs in participating countries.

Another example of multilateral cooperation is the AIRCOP programme (also supported by the European Commission) and implemented jointly by INTERPOl and the World Customs Organisation (WCO). Its primary goal is to strengthen cooperation and intelligence exchange between airports in the three continents.

Defence cooperation

As suggested above, the US military play an important support and coordination role in Trans-Atlantic counter-narcotics efforts with European governments and Spain in particular. This is particularly the case with US Southern Command and in the context of JIATF-South, as we have seen. Additionally, the US Department of Defense (DOD) Intelligence Resource Program lists Spain as one of several Partner Nations (PN) that work closely with the US to disrupt the production, transport and distribution of illicit drugs, as well as money laundering operations associated with this activity.17

In addition to the operational support and coordination with Spain, the US DOD has provided Spain with some limited funding from its ‘counter drug assistance’ programme known as Section 1004.18 Figure 4 reflects the various security aid programmes and assistance from the US DoD to Spain over the past decade. Programmes during that time have included: the Combatting Terrorism Fellowship Program, which educates and trains mid- and senior-level partner defence and security officials;19 Section 1004 Counter-Drug Assistance, which includes counter-drug activities and counter narcotics training; and Excess Defense Articles, which transfers excess defence equipment to partner nations to modernise their forces.20Figure 4. Security aid programmes and assistance from the US DoD to Spain, 2007-16

| Year | Programme | Amount (US$) | Item |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Combatting Terrorism Fellowship Program | 18,000 | |

| 2015 | Excess Defense Articles | 500,000 | Aircraft spare and repair parts F/A-18, P-3 |

| Section 1004 Counter-Drug Assistance | 94,000 | ||

| Combatting Terrorism Fellowship Program | 6,749 | Four students received counter-terrorism training in Greece and other locations at the Center for Civil-Military Relations and the US Special Operations Command | |

| 2012 | Combatting Terrorism Fellowship Program | 30,615 | National Defense University (NDU) and Special Operations Command (SOCOM) |

| 2011 | Combatting Terrorism Fellowship Program | 19,098 | George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (GCMC) and Defense Institute of lnternational Legal Studies (DIILS) |

| 2009 | Combatting Terrorism Fellowship Program | 14,948 | Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies (CHDS) and George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (GCMC) |

| Section 1004 Counter-Drug Assistance | 12,000 | Training in intel analysis | |

| 2008 | Combatting Terrorism Fellowship Program | 2,575 | George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (MC) |

| Section 1004 Counter-Drug Assistance | 10,000 | Training in intel analysis | |

| 2007 | Section 1004 Counter-Drug Assistance | 116,000 | EUCOM CN operational support |

| Section 1004 Counter-Drug Assistance | 40,000 | JIATF-South |

Source: Spain Security Aid Data, Security Assistance Monitor.

As Figure 4 makes clear, the amount of resources expended by DOD for counter-narcotics activities with Spain are minimal. Nevertheless, coordination with at least three combatant commands (Southern, Europe and Africa) are at varying degrees related directly or indirectly to counter-narcotics cooperation with Spain. With SOUTHCOM cooperation is more direct through JIATF-South, but with EUCOM and AFCOM it is either in the context of broader multilateral efforts (EUCOM) or more indirect in the case of AFCOM.

In the case of AFCOM, three of its five ‘Lines of Effort’ (LOEs) have some connection to counter-narcotics activities that are relevant to Spain. In two instances the focus is on degrading violent extremist organisations (VOE) in the Sahel and Maghreb regions, and to contain and degrade Boko Haram and ISIS-West Africa. In both cases the VOE’s are known to engage in narcotics trafficking as it enters West Africa. In a third LOE the priority is to ‘Interdict Illicit Activity in Gulf of Guinea and Central Africa’.21

According to testimony by AFCOM’s commander, US Marine Corps General Thomas Waldhouser, ‘In addition to the VEO threat throughout Africa, criminal and smuggling networks remain a persistent danger within the Gulf of Guinea and Central Africa. US Africa Command supports our African partners who work with international and interagency partners to interdict and to disrupt illicit trafficking and smuggling networks that finance trans-national criminal organizations’.

Furthermore, ‘US Africa Command (executes) the African Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership (AMLEP) and support the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, a strong regional framework for information sharing and operational coordination. In 2017, under the AMLEP, US Coast Guard and Cabo Verde security personnel embarked a Senegal Navy ship for joint patrol operations in Senegal and Cabo Verde waters’.

To the extent that narcotics trafficking to Spain includes routes in West Africa and Cabo Verde, then the work of AFCOM is relevant to Spanish counter-narcotics efforts and contributes indirectly to their success.

Conclusion

Spain’s geographically strategic location and its large consumer market make it one of the principal gateways for illicit drugs entering Europe and originating in South America, transiting via the Caribbean and West Africa. This puts Spain in a unique position of having to confront the transatlantic drug trade coming from multiple directions and using a variety of trafficking techniques. Spain’s success depends not only on its own capacities but the support and coordination it receives from many partner nations.

US counter-narcotics coordination with Spain is an important element of this strategy and, to date, has shown some important successes. Cooperation is both strong, fluid and growing, but remains limited in scope. This reflects, in part, the priority the US places on reducing the flow of drugs into the US, leaving transatlantic trafficking as an important but less vital aspect of the overall US strategy against illicit narcotics trafficking.

Nevertheless, US-Spanish counter-narcotics cooperation is occurring at many levels and in various contexts would appear to be growing and deepening. Law-enforcement cooperation, especially between the DEA and the Spanish Policía Nacional, Guardia Civil and Aduanas is the principle venue for addressing narcotics trafficking. Several successful and impressive seizures of cocaine have occurred as a result and led to a temporary market disruption. However, the growing volume of cocaine processed in Colombia suggests that the challenges of cocaine interdiction headed for Spain will only increase.

Judicial and prosecutorial cooperation are a second important element in bilateral counter-narcotics cooperation. Here there have been important successes, but also some setbacks in part because of differing judicial systems, norms and procedures that set varying standards for prosecution. These are not insurmountable challenges, but they do require continued close cooperation and effective learning by the judicial authorities from both countries. One helpful suggestion may be to fully integrate judicial authorities, such as prosecutors, in law-enforcement operations from the outset so as to avoid potential legal challenges in the prosecution phase and contribute to degrading criminal organisations through successful prosecution.

Ultimately, US-Spanish counter-narcotics cooperation is on a strong footing but has room to grow and expand further. The question remains whether new leadership in Spain and the US will prioritise this relationship.

Eric L. Olson

Deputy Director of the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program and Senior Advisor to the Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute | @Eric_Latam

Nina Gordon

Research Assistant at the Mexico Institute

1 In 2016 it was estimated that the cocaine market in Europe was valued at between €4.5 billion and €7 billion. See Europol (2016), EU Drug Markets Report: Strategic Overview, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, p. 8.

2 European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2017), Spain Country Report 2017.

3 See Ross Eventon & Dave Bewley-Taylor (2016), ‘An overview of recent changes in cocaine trafficking routes into Europe’, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; and United Nations (2016), International Narcotics Control Board Report 2016, p. 92.

4 Congressional Research Service (2009), Illegal Drug Trade in Africa: Trends and US Policy.

5 US Department of State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (2018), International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) Volume I: Drug and Chemical Control. March, p. 181.

6 The map is reproduced by InSight Crime and originally appeared in EMCDDA (2016), ‘2016 EU Drug Markets Report’.

7 Insight Crime (2018), ‘The Dominican Republic and Venezuela: cocaine across the Caribbean’, Venezuela Investigative Unit, 24/V/2018.

8 Ibid.

9 US Department of State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (2018), op. cit.

10 Ibid.

11 JIATF-South’s Area of Responsibility is 42 million square miles, 12 times the size of the US.

12 See Global Sentinel (2017), ‘8 notable security influencers in the Western Hemisphere, 1/II/2017; Department of Defense, Defense Department Intelligence and Security Doctrine, Directives and Instructions, FAS Intelligence Resource Program; and Forum of the Americas (2011), MAOC-N Nets Drugs on the High Seas, Diálogo Digital Military Magazine, 1/I/2011.

13 Description provided by US Southern Command.

14 Forum of the Americas (2011), op. cit.; and Maritime Analysis and Operations Centre (MAOC N).

15 Tribunal Supremo, Sala de lo Penal (2018), ‘Sentencia número 673/2016. Fecha de sentencia: 25/02/2016’.

16 Tribunal Supremo, Sala de lo Penal (2018), ‘Sentencia número 117/2018. Fecha de sentencia: 12/03/2018’.

17 Department of Defense, Defense Department Intelligence and Security Doctrine, Directives and Instructions, FAS Intelligence Resource Program.

18 Section 1004 refers to the section of law that authorises the US military’s involvement in counter-narcotics efforts.

19 Department of Defense (2017), ‘Historical Facts Book FY 2016’, Washington, 30/IX/2017.

20 Department of Defense (2017), ‘Defense Security Cooperation Agency, Excess Defense Articles online database’, accessed 20/XI/2017.

21 For a full explanation of AFCOM’s LOE see ‘United States Africa Command 2018 Posture Statement March 6, 2018’.