Theme

This paper presents the main results of the 2022 edition of the Elcano Global Presence Index.

Summary

The latest edition of the Elcano Global Presence Index shows an acceleration of globalisation in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite global economic tensions and the war in Ukraine. The structural trend towards the rise of Asia and, in particular, China, continues, while the EU continues to lose ground and the US maintains its share of global presence. The UK, France, Belgium, Ireland, Sweden and the Netherlands are losing global presence in both absolute and relative terms.

In addition to this structural trend, oil-producing countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have increased their positions, although possibly temporarily due to the recent evolution of energy prices.

Contrary to what is happening in other European countries, Spain is recovering its global presence with respect to the previous year, though in a context of an incomplete recovery of the tourism sector. There is thus a certain rebound effect, given the strong loss of presence in the previous edition of the Index.

Analysis

First, we analyse post-COVID-19 (re)globalisation, led, as in previous periods, by the soft dimension. Next, we look at the main changes in the top 20 positions of the Elcano Global Presence Index ranking, which reflect the continued rise of Asia and the gradual fall of Europe, as well as the possibly more transitory effect of the rise in commodity prices on the external projection of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Third, we address the US-EU-China strategic triangle from the point of view of the shares of global presence of these three global actors. Consistent with the movements in the top positions, there is an accelerated increase in China’s share of presence, while the US maintains its own and the EU loses it. In fourth and final place, we look at the Index values for Spain, which maintains its position, despite the incomplete recovery of tourism.

Post-COVID-19 (re)globalisation

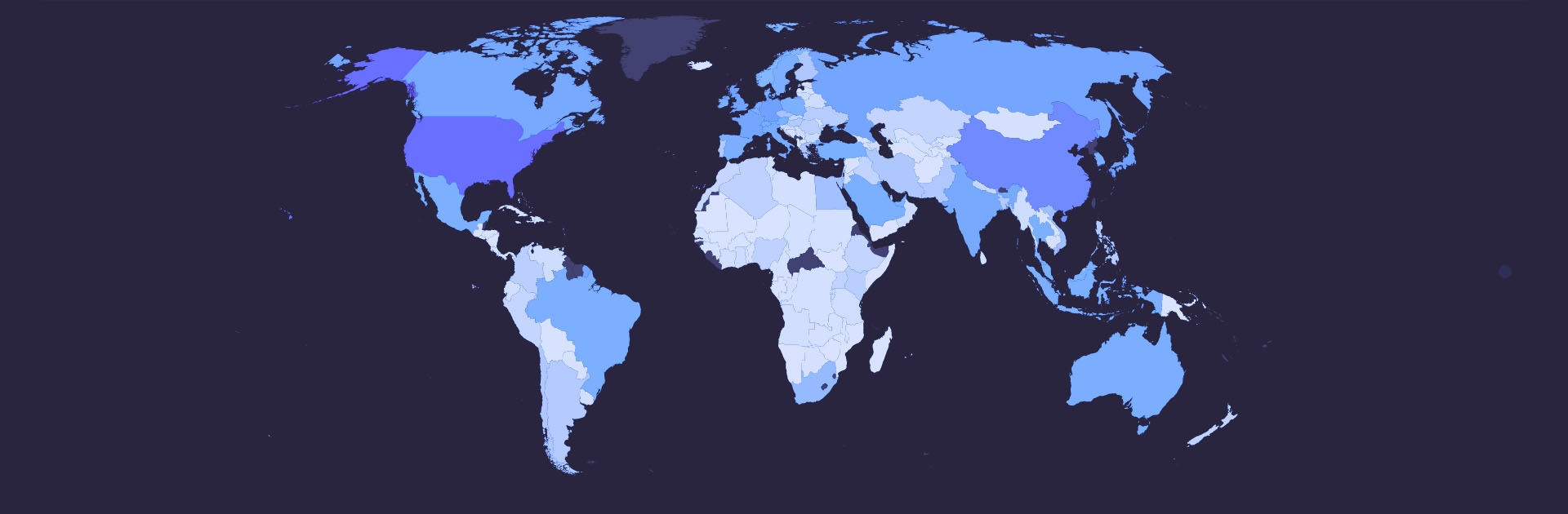

Globalisation has reached an all-time high. Calculated for 150 countries representing more than 98% of both the world economy and population, the Elcano Global Presence Index of these countries can be aggregated to show a proxy for the globalisation process. An increase in this aggregate value is thus interpreted as a sign of globalisation, and the opposite as a contraction of globalisation.

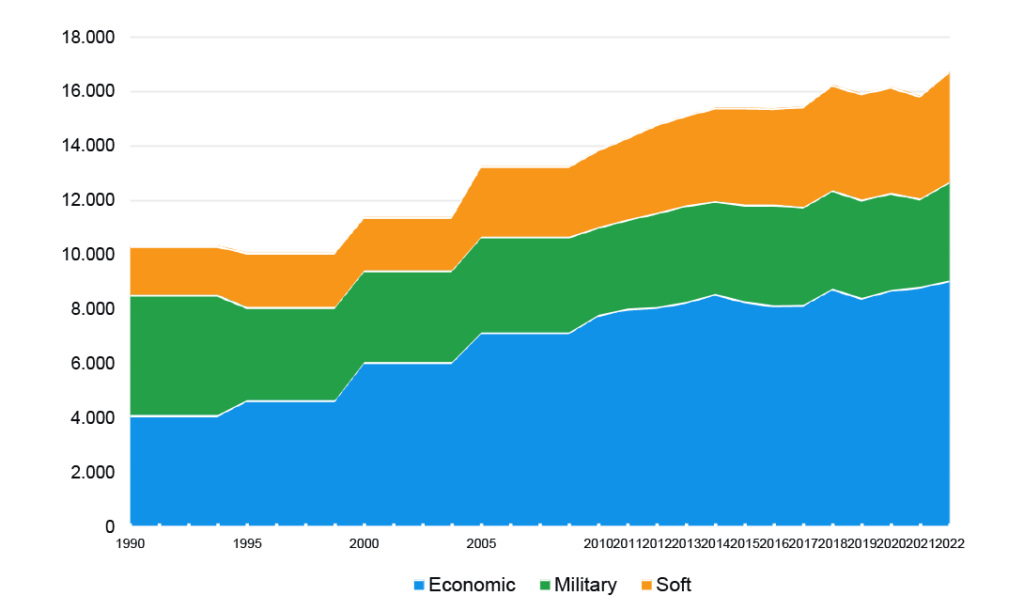

As documented in previous publications, the Index results show a stagnation of the globalisation process since the mid-2010s. After a steady growth in total global presence until 2014, when it reached around 15,500 points, a period characterised by slight rises and falls between 15,300 and 16,300 points followed thereafter. The sum of global presence for 2022 exceeds 16,700 points for the first time, showing what could be called a sort of re-globalisation, coinciding with the exit from the COVID-19 health crisis and despite the war in Ukraine and the international trade and financial tensions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aggregate value of the Elcano Global Presence Index, in index value, 1990-2022

This re-globalisation, which is manifested in an increase in total global presence of 5.6% since the previous year, is taking place in all its economic, military and soft dimensions. The military dimension, however, leads the way, with an increase of 11.6% over the previous year. This is an unprecedented value in the entire time series, which shows rather a demilitarisation of international relations in the 1990s and 2000s, a slow growth of 1.4% per year during the 2010s, and a very significant fall in the military dimension of nearly 9% last year. As will be seen below, part of this behaviour can be explained by the conflict in Ukraine but also, in more general terms, by a commitment to the growth of military capabilities in the framework of NATO.

The growth in soft projection is also very notable, at 7.4% over the previous year. The aggregate soft presence has tended to grow steadily since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Moreover, as noted in previous reports, it took the lead in globalisation in the 2010s, coinciding with a stagnant military presence and a certain economic de-globalisation following the Great Recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s. Part of the rebound in the soft dimension can be explained by the sharp drop in the previous year (-3.2%) as a result of pandemic response measures, which interrupted international movements of people via tourism or tertiary education. It is worth noting that the rise occurs in the context of only a partial recovery of international tourism, bearing in mind that this latest edition of the Index includes data for this variable for 2021. Therefore, at least as far as the tourism variable is concerned, a sharp rise in the soft dimension could be expected in the next edition of the Index.

Finally, there is also a growth in the economic dimension, 2.7% higher than last year, but lower than the previous one, which follows a contraction in this dimension between 2018 and 2019. That is, economic globalisation follows the pattern of the last decade of relatively moderate rises and falls, with no clear upward or downward trend for the time being. In terms of performance over the last year, the variables in this dimension are affected by the appreciation of the US dollar. This dimension combines a strong rise in economic presence as a result of the boom in energy and commodity prices with a sharp fall in the investment variable, measured with the stock of direct investment abroad.

In general terms, and with the military exception, which might not be sustained over time, the exit from the pandemic crisis would be similar to that of the Great Recession: the soft dimension takes the lead, as opposed to the economic dimension.

The West and the rest: more overtaking

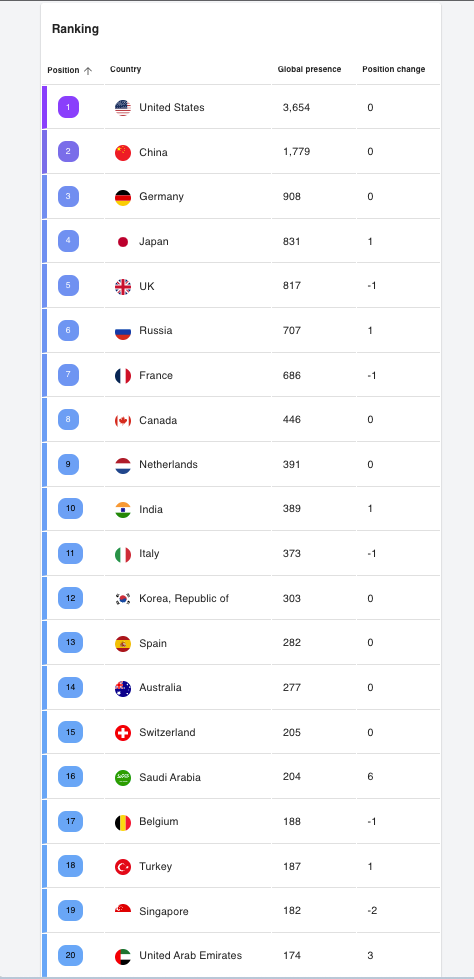

The 2022 ranking of global presence shows the confluence of structural trends that have been manifesting previously, such as the shift in world activity from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and events of a more transitory nature, such as the post-pandemic recovery, the invasion of Ukraine and the increase in energy and raw material prices, which have an impact on several indicators of the Index, economic, military and soft. As a result, this edition’s ranking presents several significant changes among its top positions.

The first position in the ranking continues to be occupied by the US with more than 3,654 points, followed by China with more than 1,779. They are also the countries that have increased their global presence the most with respect to the previous year, 315 and 202 points respectively, and they do so in all economic, military and soft dimensions. This translates into an increase in their share of global presence, that is, in the proportion of their projection in the world aggregate. But although the US is increasing its presence more than China in absolute terms, the gap between the two is actually narrowing. Thus, in 2022, the US presence is twice that of China, whereas it was three times that of China 10 years ago and nine times that of the 1990s.

Germany maintains its third place in the ranking, which it has held since it was overtaken by China in 2012. However, the increase in Germany’s presence is decreasing (21 points compared with the previous year) and is only sustained by the soft dimension in the face of an economic presence that is increasingly diminished by the lack of dynamism of its manufacturing exports.

Thus, the post-COVID-19 world is a more bipolar world centred around the US and China, while the general trend towards the emergence of Asia continues, as evidenced by the rise in the positions of the countries of this region compared with the gradual loss of positions of European countries. In this respect, Japan falls to the fourth position, overtaking the UK, which continues to lose global presence value in the post-Brexit era. India now occupies the 10th position, increasing its presence in all dimensions -economic, military and soft- reaching its record in 2022. As for Italy, it drops to the 11th position, with less global presence points today than in the 1990s.

France’s performance is similar to that of previous years, dropping to the 7th position and accumulating several years of loss of global presence value. It thus loses a position to Russia, which rises to the 6th. The latter is, after the US and China, the country recording the largest increase in global presence in the last year. Evidently, the invasion of Ukraine has had an impact on Russia’s military presence -one of the indicators of this dimension being the number of troops deployed abroad-. Its economic presence has also increased due to the growth in international prices of oil, gas and primary goods.

The current world situation is also reflected in the increased presence of oil-producing countries, which have upscaled positions in the global presence ranking. This year, Saudi Arabia, in the 16th place, and the United Arab Emirates, 20th (see Figure 2), have entered the top 20 of the ranking, while Brazil and Ireland have dropped out. In this year’s edition, the biggest increases in position were recorded by oil-producing countries, such as Chad (up 41 places compared with the previous year), Kuwait and Angola (30 and 19 places respectively).

Figure 2. Top 20 global presence for 2022 and change of position compared with the previous year

The US-EU-China strategic triangle

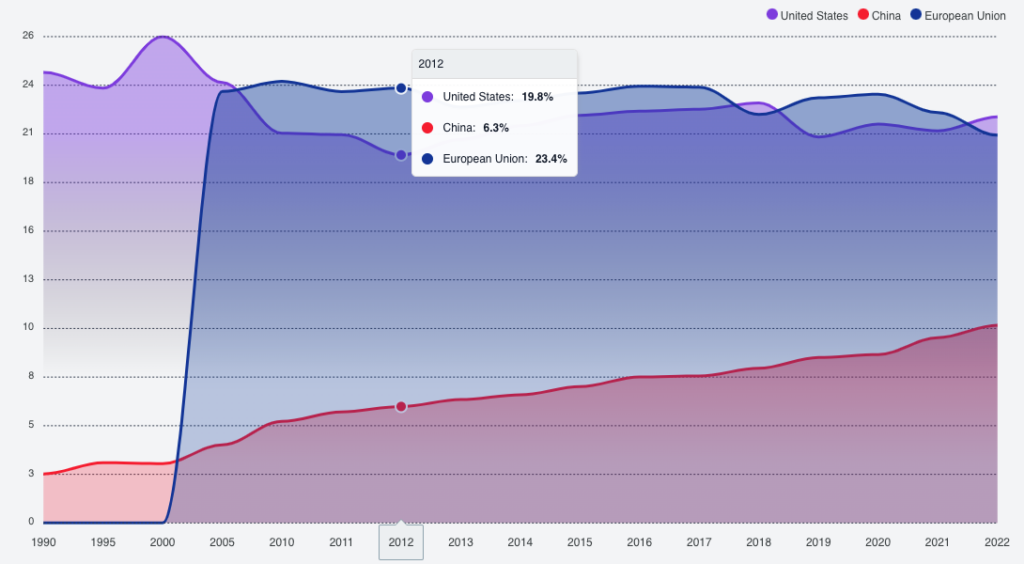

The Elcano Global Presence Index allows for the calculation of the external projection of the EU as if it were a single state, rather than the Union of 27. This measure is achieved, roughly speaking, by adding up the global presence of the 27 member States and subtracting intra-EU exchanges.

The magnitude of the external projection of this simulated EU would be similar to that of the US. Its share of global presence -the EU’s share of the aggregate global presence referred to in the first section of this paper- ranges between 20.8% and 23.7% over the period 1990-2022. The US is in the same order of magnitude, with minimum and maximum values of 19.8% and 26.1%. Moreover, this reflects the enormous geographical concentration of international relations, with half of world trade taking place from the US and Europe (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Shares of global presence: the US, EU and China, 1990-2022 (%)

In the case of the EU, there has been a gradual loss of its share of global presence, falling from 23.2% in 2005 to 20.8% at present. This is not, however, the case of the US. After reaching its peak share in 2000, the country experienced a relative loss of global presence over the following decade. After falling to a low of 19.8% in 2012, it recovered its share of projection until 2018, when values stagnated at around 21%. Nevertheless, last year’s rise of 0.7 percentage points is the highest in the last 10 years.

China’s rise as described in the previous section is matched by the evolution of its share of presence, which has quadrupled over the last three decades, rising from 2.6% in 1990 to 10.6%. It thus maintains a very large gap with the US and the EU, which it is nonetheless closing rapidly. The maintenance of the US share and the vertiginous increase in China’s, while the European share continues to fall, shows once again how the shift in the axis of international relations from the Atlantic to the Pacific is steadily taking place, as mentioned in the previous section.

Spain, resilient in the European context

The evolution of Spain’s global presence shows signs of resilience in the post-pandemic context and in comparison with other European partners.

Spain increases its global presence in 2022, whereas in 2021 it was one of the countries that suffered the greatest losses due to the impact of the pandemic and, more specifically, due to the interruption of international tourism. It maintains its 13th position in the global presence ranking, closing the gap with the 12th position held by South Korea. Among the main European partners, only Germany and Italy also record increases in presence, although mild. The UK, France, Belgium, Ireland, Sweden and the Netherlands lose ground.

Spain’s increase in global presence comes despite the fact that the recovery in tourism is only partial. In 2021 (the year taken for this indicator), tourist arrivals to Spain were only 37% of those of the previous year. By dimensions, it slightly loses economic presence due to the decline in the value of the stock of foreign investment, but gains in the rest of the indicators (energy, primary goods and manufacturing) including exports of services, again due to the partial recovery of the tourism sector. Its military presence has increased as a result of the rise in the number of troops deployed in missions (mainly Atlanta, Mali and Lebanon).

There is an increase in the soft dimension, although with a different profile to the pre-pandemic one. In the last year, Spain increased its projection in technology, science, development cooperation and climate change (in this last indicator due to the strong increase in the capacity of generating renewable energy). In the years prior to the pandemic, Spain’s soft profile was more strongly based on the indicators of migration, tourism, culture and sport. All of these are areas in which it has lost presence in the last year.

Therefore, although there has been an increase in Spain’s overall presence in the last year, this has not allowed it to recover its pre-pandemic levels. In fact, the value of presence recorded in 2022, 283 points, is lower than in 2005. In a context of the rise of other countries -mostly Asian and oil-producing countries- this has led to a reduction in its share of global presence to 1.7%, the lowest rate since 1995, with a significant fall in the variables most directly linked to international mobility. As a result, Spain loses positions in the soft presence ranking, falling from the 12th position in 2020 to the 16th in 2022.

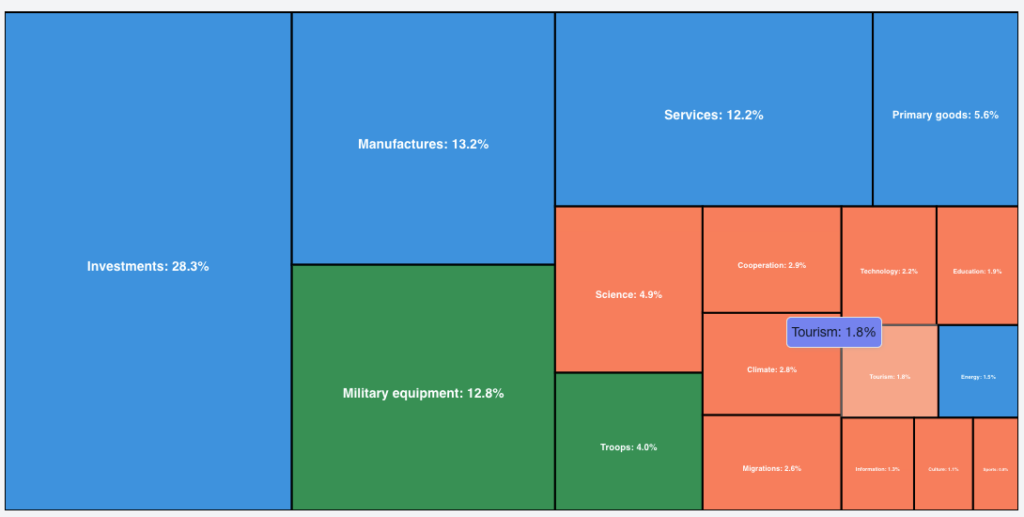

Figure 4. Contribution by variables to Spain’s global presence, 2022 (% over total)

Conclusions

The Elcano Global Presence Index data for 2022 show a recovery of aggregate global presence, a re-globalisation, following the COVID-19 pandemic and despite various de-globalising trends such as trade, financial and productive tensions and the war in Ukraine. As in previous episodes, the post-crisis recovery brings with it the acceleration of pre-existing structural trends, such as the rise of Asia and the relative decline of Europe, or the leadership of the soft dimension in the recovery. However, there are also new trends, such as the rise of the international profile of oil-producing countries and the recovery of Spain’s global presence based more on science or technology than on sports or tourism.