Theme

This study examines the preferences regarding solidarity and, particularly, asylum seekers following the 2015 refugee crisis, by comparing different European countries. Additionally, it examines how opinions on the issue have evolved over time.

Summary

The 2015 refugee crisis was considered unprecedented by the UN and the biggest of its kind in our time (UN, 2016). The answer was paradoxical. On the one hand, the EU and most European states opted to prevent refugees from entering the Union’s borders and their own countries. On the other hand, civil society showed an explosion of solidarity, with the Refugees Welcome movement being just one the many initiatives that emerged to demand a policy to take in refugees. Given such a scenario, this paper aims to explore to what extend public opinion endorses a restrictive or an open position towards asylum seekers. Additionally, it examines how opinions have evolved over time. To answer these questions, the paper uses European Social Survey data.

Analysis

Introduction

Over the past two decades the global population of forcibly displaced people has grown substantially, from 33.9 million in 1997 to 65.6 million in 2016. Growth was concentrated between 2012 and 2015, driven mainly by the conflict in Syria and other countries in the region, such as Iraq and Yemen, as well as in sub-Saharan Africa (UNHR, 2016). This global displacement has resulted in an unprecedented humanitarian crisis in Europe, not seen since the Second World War. Only in 2015, Europe recorded a large increase in the number of refugee and asylum-seeker applications, rising from around 600,000 in 2014 to 1.3 million (Eurostat, 2020).1 However, many consider the situation a crisis of politics rather than a crisis of numbers.

The initial EU call for solidarity generated uneven responses in its member states. Germany, Austria and Sweden did open their borders, promising rights and residence to refugees. However, this initial ‘opening’ moved towards a policy of closure, including border controls, tighter asylum laws and deterrence procedures (Agustín & Jørgensen, 2018, p. 11). Greece and Italy, as frontier states, were the first to deal with the reception and transit of refugees and were two of the member states to be most directly affected by the influx.Greece alone received more than 850,000 of the 1.3 million new asylum seekers who reached Europe in 2015 ( UNHCR, 2016).

Insufficient assistance to these first-arrival states caused internal tensions when they opened their borders and allowed refugees to go to their preferred country of destination. Other European states –Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland– then built fences to halt undocumented migration and rejected the European Commission’s suggested refugee quota system (Dingott, 2018). The different states’ positions on refugee policy resulted in political tension across Europe. In Agustín & Jørgensen’s words, ‘seen from an EU perspective, the worst aspect was that the EU had lost its legitimacy and was met by a lack of trust in combination with a reluctance of governments to cooperate with one another’ (Agustín & Jørgensen, 2018, p. 12).

The member states’ inability to solve the humanitarian crisis contrasted with an explosion of solidarity in the civil societies of almost all EU countries. During the second half of 2015 and in 2016 it was mainly volunteers and civil society organisations that were not only active in condemning the situation but in receiving and taking care of incoming refugees. In Austria, for instance, 2,200 drivers joined a campaign to pick up refugees stranded in Budapest. In Germany, Denmark and Sweden locals organised support for arriving refugees, donating food, water, clothes and other supplies to those in need, sometimes resorting to civil disobedience by smuggling refugees to neighbouring countries or sheltering them privately. In Iceland more than 11,000 Icelanders (out of a total population of around 323,000) offered to accommodate Syrian refugees in their private homes and pay their costs in response to the government suggesting that it would accept only 50 Syrian refugees (Agustín & Jørgensen, 2016, p. 3). Most of these initiatives were framed within the ‘Refugees Welcome’ movement, which had counterparts across many cities in Europe. Since its creation in 2015 it has been highly active in organising demonstrations, seeking donations and raising public awareness on the plight of refugees (Togral, 2016).

Simultaneously, at the local level, many towns and villages made ready to receive incoming refugees, displaying institutional solidarity. Cities like Barcelona, Paris, Lesbos, Lampedusa and Rome, among others, declared themselves willing to take in refugees and provide services to ensure they had food and a roof to live under, while at the same time demanding a greater involvement of EU institutions and more international cooperation (Agustín & Jørgensen, 2018, p. 111).

During the period, people received differing information as to how to cope with the influx of refugees: sometimes more favourable, mainly from civic engagement movements, and others less sympathetic, mainly from EU states themselves. The question is which trend has prevailed among European public opinion. The following section provides descriptive data on public preferences regarding refugees to determine to what extent public opinion endorses a restrictive or an open position towards asylum seekers.

European public opinion on refugees and asylum-seekers

There is no doubt that the ‘Refugees welcome’ campaign and other similar movements, along with the mass media and political discourse during the so-called refugee crisis, have permeated people’s attitudes towards refugees. But, how? Are there differences between European countries? How has the opinion on refugees evolved over time? Did the 2015 crisis have a direct impact on the level of support for asylum seekers?

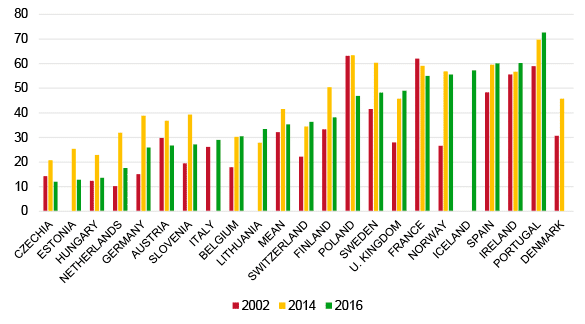

A first glimpse is provided by the European Social Survey Studies, ESS 1 (2002), ESS7 (2014) and ESS8 (2016), as they contain questions that reveal the support for refugees and asylum-seekers across Europe. Figure 1 shows the percentage of those who agree and strongly agree with the statement that the ‘government should be generous with judging applications for refugee status’ for the three waves. It is interesting to have the figures for 2014 and 2016, since although 2015 was the turning point for the refugee crisis, the became relevant earlier, some authors pointing to 2012. By 2014 there had been a slight increase in the inflow of refugees but it was not until mid-2015 that the numbers dramatically increased and that the EU member states faced a collapse in providing a solution. Thus, 2014 and 2016 can serve to show how European opinion changed before and after the refugee crisis. Furthermore, the 2002 study provides a baseline year to know what the opinion was on the refugee issue untainted by the 2008 economic crises or other immigration factors.

Considering 2016 alone, there are clusters of countries that are more and less supportive towards refugees. On the hand, in Portugal, Ireland, Spain, Iceland, Norway and France more than 50% of the population agree with the statement that their governments should be generous when judging applications for refugee status. On the other hand, there are other countries where the figure is below 50%: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and the Netherlands are the least supportive, with less than 20% agreeing with the statement.

Considering opinion over time, it can generally be said that in 2014 Europe’s citizens had a more positive opinion on refugees than in 2002. The trend can be seen in all countries (with the exception of France, with only a 3% decrease). Thus, Norway (up 30.22%), Germany (24%), the Netherlands (22%), Slovenia, Sweden, the UK, Finland (all around 17%-20% more) recorded the highest increases in support levels.

Nevertheless, if in 2014 practically all countries changed towards a more positive view on refugees, in 2016 they became more negative. Comparing 2016 with 2014, seven out of 19 countries saw a slight improvement in their opinion on refugees (up around 3%). The other countries saw their support for refugees decline. Leading the decrease was Poland, with 16 percentage points less in 2016 than in 2014 as regards the opinion that the government should be generous when judging applications for refugee status. Close to Poland were the Netherlands, Germany, Estonia, Finland, Sweden and Slovenia, all with a decrease of around 12 percentage points.

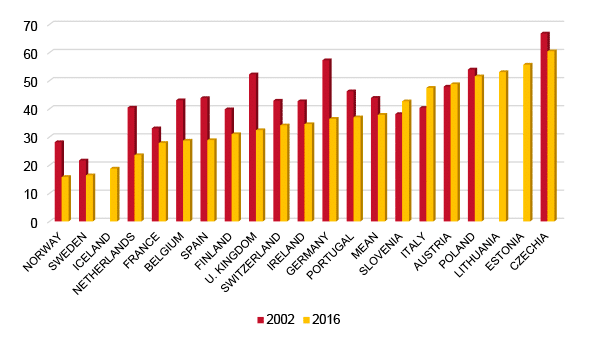

In line with these results, Figure 2 shows that in 2016 Norway, Sweden and Iceland were the countries least likely to believe that most refugee applicants were not in real danger of persecution in their own countries, at less than 20%. On the opposite side, more than 50% of people in Poland, Lithuania, Estonia and the Czech Republic agreed with the statement. Unfortunately, the 2014 ESS study did not include this item, but comparing 2016 with 2002 it can be seen that practically all countries (15 out of 18) were less prone to believe that refugees were not in real danger of persecution.

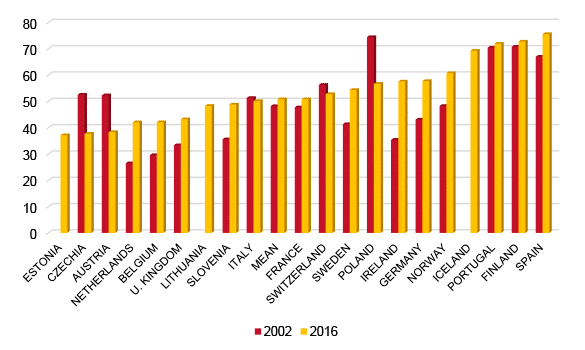

Figure 3 shows the percentage of individuals who agree with the opinion that refugees granted asylum should be entitled to bring over close family members. This statement shows the greatest homogeneity across countries as in 2016 the response was mostly above or near the 50% approval mark for accepting refugee family reunification. Over time it can be seen that Europeans were more supportive of reunification in 2016 than in 2002. However, there were three countries that recorded a substantial reduction in support: Poland (18 percentage points less in 2016), the Czech Republic (15%) and Austria (14%).

Explaining opinion on immigrants and refugees: the state of the art

There is a substantial literature on the factors determining the attitudes towards immigration. The explanations underlying opinions on the refugee issue can be divided into individual and contextual determinants. Within the individual factors, scholars have generally differentiated between socio-demographic, economic and rational explanations and social-identity characteristics. There is a clear empirical consensus that the higher the level of education the greater the support to immigrants. However, gender and age show diverging results (Dempster & Hargrave, 2017; Bansak et al., 2016; Hainmueller & Hopkins, 2014). Framed within the ‘contact theory’ or ‘halo effect’, findings indicate that contact with immigrants fosters more favourable attitudes. The rationalist approach shows that there is scant evidence that an individual’s economic situation influences his attitudes towards immigration. It is the opinion on the national economy –ie, sociotropic concerns– that drive attitudes towards immigration (Sides & Citrin, 2007). This perspective posits that opinion is likely to be influenced by symbolic interests such as cultural values or territorial identities. In this way, some studies conclude that immigration-related attitudes are mostly driven by national identity (Hainmueller & Hopking, 2014, p. 226-235) and that cultural values play a decisive role in contrast to contextual or economic determinants (Sides & Citrin, 2007).

At the crossroads of these approaches there are studies that disaggregate the characteristics of migrants. High-skill immigrants and the perception that they can contribute more than low-skill immigrants to the economy of their country of destination makes them more positively valued. Individuals also discriminate by ethnicity. Muslim and/or non-white ‘others generate public resistance to admitting these groups’ (Steele & Abdelaaty, 2018; Goodwin et al., 2017). A 2016 Chatham House survey of 10,000 people in 10 European states found that 55% agreed with the statement that ‘all further migration from mainly Muslim countries should be stopped’, with particularly strong support for this sentiment in Austria, Poland, Hungary, France and Belgium (Goodwin et al., 2017).

Despite the myriad studies devoted to understanding attitudes towards immigrants, there is still little scholarly research on attitudes towards refugees. Nevertheless, there are notable exceptions (Coenders et al., 2005; Bansak et al., 2016, Steele & Abdelaaty, 2018) and all conclude that individuals do not perceive immigrants and refugees equally. For instance, Coenders et al. (2005) find that the determinants of resistance to asylum seekers were less pronounced than with immigrants. They explain that the general public is less divided on asylum seekers, possibly due to differences in the strength of compassion that asylum seekers and immigrants evoke amongst the broader population (Coenders et al., 2005, p. 24). One of the most recent studies conducted in 15 European countries shows, on the basis of a joint experiment, that economic, humanitarian and religious concerns are powerful determinants of attitudes toward asylum-seekers across all types of profiles. Thus, high-skilled asylum-seekers –in contrast to those with low skills– that speak the host country’s language and those claiming they are persecuted on political, religious or ethnic motives grounds –in contrast to those who migrate to seek better economic opportunities– are more likely to be accepted. Similarly, Muslim asylum-seekers are less likely to be accepted compared with otherwise similar Christian asylum-seekers (Bansak et al., 2016).

However, this individual-level research has limitations in explaining variations across countries and across time. In this respect, contextual factors can provide better explanations on why public opinion in some countries may be more favourable to receiving asylum seekers, or why general opinion changed after the 2015 crisis. The majority of these contextual studies have focused on economic conditions as macro-level economic predictors (Coenders et al., 2005, p. 24; Messing & Ságvári, 2018; Sides & Citrin, 2007). Thus, individuals living in better economies –mostly reflected by per capita GDP– have more positive attitudes towards immigrants. Other factors such as the number of asylum applications (Coenders et al., 2005), do not have statistical significance or have little impact on public opinion. Despite this initial evidence, aggregate level studies are still in their infancy and more research is necessary, particularly after the 2015 crisis. Beyond economic explanations, there is a need to include factors that capture political competition to better understand how context shapes attitudes towards refugees across countries. The following section provides initial evidence on how political competition matters.

Far-right parties and their effect on attitudes towards refugees

It is during 2015 and afterwards, that immigration is highlighted by European citizens as one of the most important issues facing the EU and their national states (Glorius, 2018; González Enríquez, 2017). The saliency of the refugee issue was also a central topic on the political agenda. This implies political parties presenting policy positions on refugees, and competing to become the voter’s focal party to address this topic, what is known as issue ownership (Neundorf & Adams, 2018). In this political contest, the existence –and electoral strength– of far-right parties can be a determining factor on how they establish preferences on refugee policy. The core ideology of radical right-wing parties is to restrict immigration and multicultural societies (Gómez-Reino, 2019). Thus, parties can adopt a more negative position on refugees than they would otherwise have if extreme right-wing parties are absent. In this respect, Han (2015) finds that the rise of radical right-wing parties has given rise to more restrictive positions regarding multiculturalism, with left-wing parties doing so only when their supporters become more negative about immigrants or when the parties themselves lose votes to their right-wing opponents.

When extreme right-wing parties are strong they can have a negative influence on the opinion of individuals towards refugees; they can also shape other parties’ positions towards a more restrictive view on refugees, which can –in turn– further influence public opinion in the same direction. To test this argument, it is necessary to run statistical models to control for other factors, beyond the strength of far-right parties, that can affect attitudes towards immigrants and refugees. This can provide a clearer association between the vote share of right-wing parties and attitudes towards refugees.2

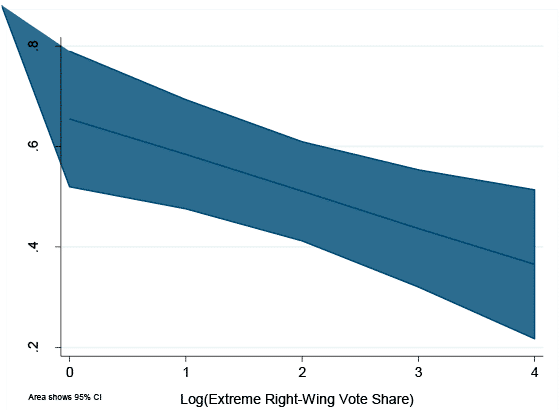

To capture preferences towards the refugee issue, the ESS 2016 data explained above can again be used, while the statement that ‘Government should be generous at judging applications for refugee status’ can be used as the dependent variable (see Figure 1).3 Using a logit regression model, Figure 4 shows the expected probability of believing that governments should be generous when judging asylum-seeker applications according to the vote share of extreme right-wing parties. When the vote share of far-right parties increases, the likelihood of agreeing with such an opinion decreases. Thus, Hungary, Slovenia and Austria, with a high level of support for these parties, are also among the countries that are less in agreement with having a generous governmental policy on receiving refugees.

However, although the electoral strength of these parties shapes public opinion –towards a more restrictive refugee policy–, this is just one of many political factors that can influence attitudes towards refugees. Additional factors should be considered, particularly those that reflect the conditions under which these parties succeed in shaping policies and voters’ preferences towards refugees. More studies on these topics should shed some light on how public opinion views refugees and asylum-seekers.

Conclusions

The unprecedented arrival of asylum seekers in 2015 gave rise to political turmoil in the EU, giving the inability of member states to provide an effective solution to the 1.3 million asylum seekers waiting at Europe’s borders. Although initially some countries were sympathetic –including Germany and Sweden–, they became less so as the masses of refugees increased. Other countries, like Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, adopted a sharply negative position from the very beginning, closing their borders and preventing the entry of refugees. This unfavourable institutional solidarity contrasted with an explosion of social solidarity. The Refugees Welcome movement and many other initiatives emerged from civic society to demand that their countries take in refugees and provided accommodation and primary services to the new arrivals.

These paradoxical attitudes permeated public preferences towards asylum seekers. As commented above, in 2014 –compared with 2002– public opinion moved towards a more favourable position on the refugee issue. In fact, the 19 European countries analysed saw an increase in the percentage of people agreeing that governments should be generous when judging applications for refugee status. However, in 2016, just after the massive inflow of asylum-seekers and the EU’s political collapse, public preferences turned towards a more restrictive view on refugees. In fact, 12 out of 19 countries recorded a drop in the opinion that their governments should be generous when judging refugee applications. The decrease was remarkable in many countries, exceeding 12 percentage points in Estonia, the Netherlands, Germany Austria, Slovenia, Poland and Sweden. But in other countries the drop was less significant because the starting point was already low in 2014, as in Hungary and the Czech Republic, and was still very low in 2016 (with only around 12% agreeing with the statement). These two countries, along with Estonia, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria and Slovenia, head the list of countries that are least empathetic towards asylum seekers.

Analysing why some countries have individuals who are more prone to policies aimed at taking in refugees shows how the strength of far-right parties matters. Thus, when the vote share of these parties increases, the support of individuals for refugees declines. In view of this initial result, and the rise that extreme right-wing parties have experienced across Europe, more research is required on the dynamics of political competition, as it can be a determining factor in explaining the public perception of refugees across countries and across time.

Sandra Bermúdez

Department of Political Science and Administration, National Distance Education University (UNED)

Additional references

Gómez-Reino, M. (2019), ‘“We First” and the Anti-Foreign Aid Narratives of Populist Radical-Right Parties in Europe’, in Iliana Olivié & Aitor Pérez (Eds.), Aid Power and Politics, Routledge, pp. 272-284. doi: 10.4324/9780429440236-16.

Goodwin, M., T. Raines & D. Cutts (2017), ‘What do Europeans think about Muslim Immigration?’, Chatham House, London.

1 However, the number of asylum-seeker applications within the EU’s member states was far from equal. Countries like Germany, Hungary, Italy and Austria registered the largest increases in 2014 and 2015. Germany was the country to receive the largest number of applications, at almost 500.000 in 2015 and 750.000 in 2016.

2 Far-right parties are considered to be those that Norris & Inglehart (2019) identify as authoritarian-populist (see p. 235-237). The list has been updated by adding the Freedom and Direct Democracy Party in the Czech Republic and The Conservative People’s Party in Estonia. The vote share has been calculated from Holger Döring & Philip Manow (2017), ‘Elections’ dataset.

3 The remaining attitudes examined explain other refugee status dimensions. For instance, believing that refugee applicants are in real danger of persecution in their own countries can explain why someone would favour an acceptance policy. Similarly, the right to bring family members is also connected with a generally favourable attitude towards refugees. If a country limits the entry of refugees, it is of no importance that the few who are fortunate request family unification since the additional entry of refugees will be limited.

4 Logit models include the following independent variables: age, gender, education level, placement on the left-right scale, satisfaction with the present state of the economy, the respondent’s emotion attachment to his/her country and with Europe and the logarithm of the far-right vote share. The dependent variable contrasts those that agree and strongly agree with the statement with those that disagree and strongly disagree. Standard errors are clustered by country to correct for unit dependence. Results are available upon request.

Syria refugee crisis. Photo: © European Union 2016 – European Parliament (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)