Summary

Technological progress has enabled the development of new assets that aim at fulfilling the functions of money. Replacing traditional money (physical or digital) with these new assets could mean, among many other changes, extending at least part of the process of money creation beyond the current regulated framework. In this context, two complementary approaches emerge in the European Union: on the one hand, the regulation of markets of crypto-assets issued by private agents; on the other hand, the direct provision by the public sector of an alternative digital asset. The Spanish authorities have also reacted to the increasing relevance of cryptoassets, both from a supervisory and regulatory perspective.

Analysis

Introduction

Citizens and companies use as means of payment either cash, provided by the Central Bank, or digital money under different formats such as deposits or e-money, provided by private regulated entities.

Technological progress has enabled the development of new assets that aim at fulfilling the functions of money: unit of account, means of payment and store of value, all at the same time. These combine the features of cash, such as privacy, with those of digital money, like for instance security or the ability to undertake large transactions conveniently. In recent years, hundreds of alternatives, real or potential, have emerged, including Bitcoin or Libra-Diem.

Replacing traditional money (physical or digital) with these new assets could mean, among many other changes, extending at least part of the process of money creation beyond the current regulated framework. This has direct implications in terms of consumer protection, which is why regulatory measures are being discussed in almost every country. Further, if widely preferred and used over fiat money, it could threat monetary sovereignty: control of money could cease to be largely in the hands of the Central Bank and regulated institutions.

In this context, two complementary approaches emerge in the European Union, with which the EU seeks to create a flexible yet stable framework that guarantees the protection of the consumer and other public goods such as financial stability, monetary sovereignty or financial innovation:

- On the one hand, regulating markets of crypto-assets issued by private agents, both in their more standard uses (digital transmission of securities or rights) and in those with monetary policy implications. In this regard, the European Commission has recently published its proposal for a Markets in crypto-assets (MICA) regulation.

- On the other hand, the direct provision by the public sector of an alternative digital asset, which allows for combining the benefits of a new form of digital money while maintaining the, respectively, direct and indirect control of the Central Bank on the determination of the monetary base and the money supply.

In this article, we introduce the concept and current reality of crypto-assets and more particularly payment tokens. We will also provide some details on what the current regulatory initiatives are.

The article is structured as follows: in Section 1, we define crypto-assets, present a simple taxonomy and focus on the evolution of payment tokens. Then, in Section 2, we give an overview of the regulatory response at the international and European levels. Section 3 presents the first steps towards the possible provision by the public sector of an alternative digital asset. Finally, Section 4 provides a summary of the supervisory and regulatory responses in Spain.

(1) Taxonomy of crypto-assets and the evolution of payment tokens

(1.1) Taxonomy of crypto-assets

At present, there is no common official definition for crypto-assets. Different financial institutions, such as the ECB, FSB, IOSCO, EBA, ESMA have a definition of their own. Yet, some elements coincide in these definitions, namely, (1) the use of some form of distributed-ledger technology to record the asset, (2) the private nature of the asset, which is neither issued nor guaranteed by a public authority and (3) the use of the asset for payment or investment purposes.

Crypto-assets can broadly be divided into two categories: on the one hand, payment tokens; on the other hand, investment and utility tokens.

- Payment tokens, also known as crypto-currencies, were the first to emerge with the appearance of Bitcoin back in 2008, with the aim of serving the purpose of means of payment. As will be explained in the next sub-section, payment tokens can be “non-backed” or “backed”.

- Investment and utility tokens basically consist of a digital representation of rights and started being used in 2017. Investment tokens grant the holder with the right to participate in the profits of the underlying asset or issuer. Utility tokens can either enable access to a specific current or prospective service or good or reward operators for services they provide.

(1.2) Payment tokens

Alternatives to public money backed by a government have been common in history. They usually gain force in moments in which there is a rapid increase in demand or credit, or some agents believe a more effective means of payment and store of value can be established beyond the control of a centralized monetary authority and the existing banking regulation.

On this occasion, it was with the financial crisis in 2008 that ideas to create a private decentralized means of payment gained traction, leading to the birth of Bitcoin. Bitcoin is a “non-backed” payment token. “Non-backed” payment tokens do not count on any underlying asset or right to serve as a possible guarantee. Since they are not under the control of a public authority either, they are prone to episodes of potentially high volatility, which heavily impairs their possibility to serve the purposes of means of payment or store of value.

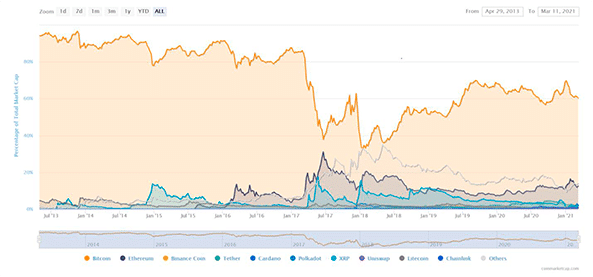

In spite of the potential volatility these type of assets entails, since 2011, a significant number of other initiatives have entered the market, given the low entry barriers into this market. These alternatives are better known as Altcoin (a term used to refer to all “non- backed” payment tokens other than Bitcoin). Currently, according to Coinmarketcap, there are 4,219 listed cryptocurrencies, with a combined capital market value of $1.5 trillion ($0.9 trillion correspond to Bitcoin). Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 2, though Bitcoin is still the prevailing “non-backed” payment token in terms of market capitalization, its relative share has decreased. The reason why Bitcoin is still dominant is related to network effects: when a payment token enters the market for the first time, its network is smaller than that of the incumbent and thus, users do not see as many benefits in participating to this initiative, even when those new initiatives overcome some of Bitcoin’s limitations (limited supply, excessive energy consumption, etc.)

In order to prevent the excessive volatility of “non-backed” payment tokens, backed crypto-currencies appeared later on. “Backed” payment tokens rely on the backing of some kind of guarantee or right over assets or over an identified issuer, and are commonly known as “stablecoins”. This is, in our view, a misleading term, skilfully introduced to serve commercial purposes. Indeed, the existence of some assets or claim over the issuer to serve as a guarantee does not imply that the value of the crypto-asset will be stable. Insofar as neither stability nor usability is guaranteed, these assets are more often than not neither “stable” nor actual “coins”.

There are basically three types of stabilization mechanism for “backed” payment tokens. First, a payment token can be backed by existing official currencies. This is the case of USD coin (Coin base), which is backed following a 1:1 peg with the US dollar. Second, a payment token can be backed by other payment tokens, this being the case of Tether. Finally, other payment tokens, known as “algorithmic”, do not use any other assets as guarantee, but rather create or destroy tokens in order to adjust their value.

All the above mentioned “backed” payment tokens are, at least for the time being, of a rather limited scale. Yet, in June 2019, the Libra Association made public a Whitepaper outlining the features of a “backed” payment token, known as Libra, that would be launched in 2020 and that would have the potential to reach a global scale (the Libra Association was backed by dozens of companies, the most active one being Facebook, which was expected to use all the resources within its reach to promote the project). Libra would be backed by a basket of currencies and other safe assets, such as US Treasury securities. A number of financial supervisors and regulators were immediately alarmed by the potential financial stability risks such an initiative could lead to. This had a clear impact both on the membership of the Libra Association (by October 2019, a number of members left the Association, such as PayPal, eBay, Mastercard, Stripe, Visa or MercadoPago) and on the design of the initiative. In January 2020, the Libra association moved from being a payment token backed by a basket of currencies to a combination of a payment token that would be backed by a single currency ( e.g., ≋USD, ≋EUR, ≋GBP, etc.) and a multi-currency coin (LBR) backed by a basket of its single currency crypto-assets. Thus, the re-baptised “Diem project” is more similar to a new payments system with broad scope than to a new form of private money, although doubts remain about the LBR multi-currency “coin”.

(1.3) Main risks of payment tokens

Starting in 2018, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) undertook work to consider risks to financial stability from crypto-assets. Its work concluded that based on the available information, crypto-assets did not pose a material risk to global financial stability at that time. However, it also considered that vigilant monitoring was needed in light of the speed of market developments.

The truth is that the share of cryptocurrencies in global payment transactions is still marginal. Nowadays, cryptocurrencies are mainly used with investment purposes, generally of highly speculative nature.

Nonetheless, there is a clear need to monitor the evolution of these initiatives, which could ultimately pose significant risks to financial stability. Beyond the volatility of the value, which could entail risks from an investor protection point of view, other sorts of risks need to be adequately catered for, namely:

- Money laundering and terrorism financing risks.By providing anonymity and digital means to operate, cryptocurrencies have facilitated the development of online illegal marketplaces. According to an analysis by the University of Sydney1, via Bitcoin, around $ 76 billion were used in illegal activities. At the time, this amounted to 46% of Bitcoin transaction, with 26% of Bitcoin users being involved.

- Financial stability risks. According to the ECB, if crypto-assets were used as a store of value, they could impair the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Among other reasons, because if stablecoins were used as a store of value, this would increase the demand for safe assets, which could, in turn, lead to scarcity of eligible assets for central bank policy operations such as asset purchases and open market operations. 2

- Legal risks given the lack a regulatory framework that could provide protection mechanisms against the breach of a contract. On top of this, in some cases, such as Bitcoin, the absence of an issuer (legal person responsible for the issuance) creates additional challenges, as explained under Section 2.

- Loss of private keys.To avoid intermediaries, crypto-asset transactions require a private key, which is personal and cannot be recovered in case of loss. According to some estimates, around 20% of Bitcoins are irremediably lost.

- Energy consumption. Bitcoin’s “mining” process requires substantial energy. This is creating increasing environmental concerns.

(2) Regulatory response

(2.1) FSB on crypto-currencies

In June 2019, the G20 called on the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to examine regulatory issues raised by “so-called global stablecoins”. The result was a consultative document published in April 2020, which, amongst others, included a list of ten “high-level recommendations” that seek to “promote consistent and effective regulation, supervision and oversight”.

These included a recommendation to regulate and supervise global stablecoins, to apply regulatory requirements proportionally to the risks they each pose, to ensure that stablecoin arrangement have in place robust plans for recovery and resolution, and, crucially, that “where a stablecoin is used widely for payment purposes, authorities should assess whether safeguards or protections consistent with similar instruments are appropriate. Where a global stablecoin arrangement for such a stablecoin offers rights to redemption, such redemption should be at predictable and transparent rates of exchange, including, where authorities consider it appropriate, at par into fiat money consistent with similar instruments used widely for payment purposes.” This recommendation will be crucial in the assessment of current regulatory proposals in Europe.

(2.2) Joint Statements by the EU Council, the European Commission and the five largest EU Member States

Before the European Commission came out with its legislative proposal to establish a comprehensive framework regulating crypto-assets (MICA), some EU institutions and Member States launched a clear message to the outside world and to the promoters of crypto-ideas with the potential to put financial stability at risk. This was the case of the joint-statement by the Council of the EU and the Commission, of December 5th 2019, where it was stated that “no global “stablecoin” arrangement should begin operation in the EU until the legal, regulatory and oversight challenges and risks have been adequately identified and addressed.”

This statement was followed by the Joint Statement issued by the Finance ministers of the five largest EU Member States, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain, on September 11th, 2020, a few weeks before the MICA proposal was published. The penta-country statement listed a number of principles on which any regulation on “asset-backed crypto-assets” (“backed” payment tokens, following our terminology) should be based:

- Each unit of asset-backed crypto-asset created shall be pledged at a ratio of 1:1 with fiat currency.

- The assets eligible for the reserve shall be limited to deposits, deposited in a credit institution approved by the European Union, or for a fraction to highly liquid assets, subject to appropriate safeguards to be put in place.

- The assets eligible for the reserve shall be denominated in euro or a currency of a Member State of the EU, be held separately from other reserves and be nonconvertible in order to avoid exchange rate risk.

- For asset-backed crypto-assets that are intended to be used widely for payment purposes, users shall have a direct claim on the reserve and the issuer so that the user can redeem, at any moment and at par value, the asset-backed crypto-asset into legal tender.

- All entities operating as part of an asset-backed crypto-asset scheme in the EU shall be registered in the EU before starting any activity

(2.3) MICA

As mentioned in the introduction, two complementary approaches have emerged in the EU as a response from the public sector to the increased relevance of crypto-currencies. The first one is purely regulatory: a new market needs a new set of rules.

Last September, the European Commission presented, as part of its Digital Financial Strategy, a comprehensive draft regulation proposal on crypto-assets, also known as MICA. MICA aims to “harmonise the European framework for the issuance and trading of various types of crypto tokens”. In particular, MICA establishes obligations on the issuers of crypto-assets and providers of services comparable to those that apply to the financial sector, but adapted to their specific risk characteristics. The proposal has four main objectives: i) providing legal certainty, ii) establishing uniform rules for issuers of crypto-assets and service providers, iii) replacing existing national frameworks and iv) establishing rules for so-called “stablecoins”.

The proposal covers any crypto-asset that is not addressed by other legislative instruments (financial instruments, electronic money, deposits and structured deposits, etc.) or issued by the European Central Bank. It must also be noted that the issuance of decentralized payment tokens, such as Bitcoin, also remains beyond the scope of the regulation, as there is no central issuer to whom obligations can be imposed. The legislative proposal addresses this only through the regulation of crypto-asset service providers. We may not be able to regulate the issuance of Bitcoins, but we can certainly regulate the activities of those that exchange them, store them or advise clients on their Bitcoin operations.

Bearing this in mind, MICA distinguishes, on one hand, crypto-assets in general, for which it contains a specific set of rules, and on the other hand, what it calls Asset-referenced tokens (ART) and E-money tokens (EMT), for which another, more stringent, type of regulation is foreseen. Building on the classification presented under section 3, crypto-assets in general would match “non-backed” payment tokens, whereas ART and EMT would correspond to “backed” payment tokens.

Regarding all crypto-assets which are not ART or EMT, i.e. “non-backed” payment tokens which are not already covered by previous financial regulation, the proposed Regulation requires these to be issued by legal entities, not necessarily established in Europe, following the publication of a white paper, unless they fall within a set of exceptions. This whitepaper will not require prior approval by the authorities. A number of behavioral requirements are also imposed on issuers, which will be very familiar to those accustomed to dealing with MiFiD II requirements.

Of course, MICA also covers “backed” payment tokens, also miscalled in the financial world as stablecoins. As already mentioned, these are specific types of crypto-assets whose special feature is that they purport to maintain a stable value by using different stabilization mechanisms based on a reserve of assets. The difference between the two concepts created by MICA is that, while in the case of EMT the stability mechanism is related to a single currency, ART purport to maintain a stable value “by referring to the value of several fiat currencies that are legal tender, one or several commodities or one or several crypto-assets, or a combination of such assets”. It is this concept of multi-asset basket that has so far been highly problematic in the negotiations in the Council of the EU.

The Commission´s proposal considers that EMT are very similar to e-money – in fact, EMT are deemed e-money – which is already regulated by a Directive (EMD2). Crucially, only credit or electronic money institutions will be allowed to issue EMT, and consumers will have a right over the issuer to at par redemption at all times. In other words, if you are the owner of an e-money token linked to the euro, you will always be entitled to get your euro back from the issuer, nearly free of charge, in the very same way that PayPal must redeem in actual euros your euro balance on your PayPal account. It is difficult to understate the importance of this requirement: on top of consumer protection motives, it guarantees that no monetary creation takes place in the process of issuing and trading EMT.

ART, on the other hand, are regulated differently under the Commission´s proposal. Any legal person established in the European Union (note the additional requirement) can issue an ART, subject to prior authorization by National Competent Authorities, which will take a close look to the extended version of a white paper that is required from them. In this process, the ECB would issue an opinion, which would not be binding.

Both for ART and EMT, the regulation proposal includes additional requirements when these attain a certain scale and become “significant”.

As indicated above, the proposed regulation also covers crypto-asset service providers,which is of utmost relevance when it comes to the control of initiatives such as Bitcoin, where the lack of a centralized issuer makes it necessary to establish control mechanisms over the agents exchanging, storing or advising clients regarding these types of assets. A total of eight types of services are defined, including custody and administration on behalf of third parties, operation of trading platforms or the exchange of crypto-assets for official currencies or other crypto-assets. In order to provide crypto-asset services, companies will need to receive prior authorization from national authorities. This authorization will then be valid across the Union. Credit institutions, as well as companies which are already authorized to provide the same services under MiFiD, will not necessitate such prior authorization.

(2.4) Negotiation in the Council

The negotiations at the Council of the EU level started swiftly after the proposal was published last year, and are still ongoing.3 Though the proposal entails a significantly positive step, which will put the EU at the forefront of the regulation in crypto-assets, some amendments may be warranted to the current proposal, inter alia, regarding the need to further clarify the taxonomy of crypto-assets, the importance of streamlining supervisory and notification processes especially when it comes to whitepaper notifications or the need to enhance the suggested framework for ART to prevent potential financial stability disruptions.

On 19 February 2021, the ECB issued its legal opinion, in which it considers that both ART and EMT have a “significant monetary substitution dimension”. ARTs have a higher financial stability risk than EMTs, as they are more likely substitutes for existing money. Indeed, contrary to e-money, which is denominated in euros or other official currencies, each ART would have its own denomination. MICA subjects ART issuers to lower regulatory requirements than EMTs. In particular, issuers need not have a credit institution or e-money institution license, and although both types of assets are subject to strict regulation in terms of mandatory registration in Europe, transparency or the management of the reserve (higher in case they are defined as “significant”), holders of ART will not necessarily have a direct claim on the issuer or the reserve. This is, in our view, highly problematic. Under the current proposal, MICA would be creating a new category of payment instruments which would not be aligned with the current requirements of such instruments in European financial legislation (read, PSD2 or EMD2).

Furthermore, there are doubts about the implications of the Commission’s proposed rules on reserve management in terms of bank disintermediation (substitution of deposits for crypto-currencies, increasing the cost of funding for banks, among other effects) and on government bond markets, potentially causing fragmentation of sovereign debt markets in the Eurozone in the event of an ART reaching a significant level.

There are also doubts about the possibility of regulatory arbitrage: it would be enough to include a minimum percentage of another currency or asset in the crypto-currency’s backing pool to change it from an e-money token to an asset referenced token. These are currently being tackled in the Council negotiations.

(3) Direct response: provision by the public sector of a digital euro

The complement to regulating private crypto-currencies is the direct provision by the public sector of an alternative digital asset which could be used for payment purposes, in particular cross-border. This could allow combining the benefits of a new form of digital money while maintaining the influence of the Central Bank on the determination of money supply.

The debate has accelerated since the first Libra announcement in 2019. On October 2 2020, the ECB published the first report of its High-Level Task Force on Central Bank Digital Currencies. While no decision has yet been taken on the design of the eventual currency, the ECB has stated some desired characteristics: it favors a universally accessible currency (to be used by citizens and businesses) but mediated by the private sector. This would rule out providing citizens direct access to accounts in the Central Bank. The publication of this first report highlights a somewhat sovereignist approach, which presents CBDC as an instrument of strategic autonomy from foreign payment service providers or potential private money issuers.

It must not be forgotten, though, that whilst regulating crypto-assets or issuing a Central Bank Digital Currency are highly technical topics, they are no less political. Different types of crypto-asset regulations, or different CDBC designs, are likely to have significant policy implications, for example in terms of the role the euro plays abroad – or other currencies, private or public, play in Europe – but also in terms of the role of financial intermediaries, accessibility to public money or national security.

(4) Measures adopted in Spain in the supervisory and regulatory fields

The Spanish authorities have also tracked very closely the evolution of crypto-assets and their possible impact on investors’ protection and financial stability, adopting a number of supervisory and regulatory measures, as explained below.

(4.1) Supervisory measures

Banco de España (BdE) and Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (CNMV), in their respective supervisory capacities, have adopted two joint statements on 8 February 2018 and 9 February 2021, respectively. Both statements focused on crypto-assets, specifically mentioning Bitcoin (the latest one also referred to Ether).

The first statement highlighted a number of risks regarding crypto-assets, namely the extreme volatility of their market capitalization, the lack of regulation and supervision, the problems derived from the cross-border features of many of these assets, the potential to lose all the invested capital and the lack of adequate and transparent information for investors. This statement made special reference to “Initial Coin Offerings”, a means of raising funding by the issuance of different types of tokens.

The second statement built on the same principles, insisting on the total lack of regulation until negotiations on MiCA are finalized and the Regulation enters into force, the high risk of these type of investments, their complexity, the possible manipulation in price setting mechanisms, the very limited acceptance of crypto-assets as means of payment and the risks derived from losing passwords.

(4.2) Regulatory measures

In order to grant national supervisory authorities with more powers while MICA Regulation is still under negotiation, Royal Decree-law 5/2021, of 12 March, granted new powers to the CNMV, allowing this institution to submit to authorization processes or other sorts of administrative controls the advertisement of crypto-assets. This would also allow the CNMV to introduce warnings about the risks and features of these assets in the publicity. In this way, the Spanish government ensures that the supervisory authority has enough powers at its disposal to avoid misinformation campaigns reaching consumers.

On top of the above mentioned measure, the government expects to get this year through Parliament the transposition into Spanish legislation of the fifth anti-money laundering directive, which, as far as crypto-assets are concerned, incorporates as obligated entities, subject to registry with the BdE, a set of crypto-asset service providers such as those providing exchange of virtual currency for legal tender or other crypto-assets, as well as providers of electronic wallet custody services.

Conclusions

At this stage and according to several sources, like the FSB, cryptoassets create mostly potential issues in terms of investors’ protection. A close monitoring of the evolution by public authorities is of utmost importance, which should ideally be accompanied by proactive measures. This is the case, for instance, of the dual approach undertaken in the European Union, which combines a regulatory response (with the proposed Regulation of MICA) with the analysis of the possibility to launch a digital euro. Measures at national level, such as the ones adopted in Spain, to support the efforts of European authorities are also crucial to ensure that financial stability is under control and that investors are adequately warned and protected by public authorities.

References

Coinmarket cap, one of the most referenced price-tracking websites for crypto-assets.

CNMV, BdE, (February 2018), “Comunicado conjunto de la CNMV y del BdE sobre “criptomonedas” y “ofertas iniciales de criptomonedas”(ICOs)”.

CNMV, BdE, (February 2021),“Comunicado conjunto de la CNMV y del BdE sobre el riesgo de las criptomonedas como inversión”.

Anteproyecto de Ley, por la que se modifica la ley 10/2010, de 28 de abril, de prevención del blanqueo de capitales y de la financiación del terrorismo, y se transponen Directivas de la Unión Europea en materia de prevención de blanqueo de capitales y financiación del terrorismo.

European Parliament, (July 2018), “Cryptocurrencies and blockchain: Legal context and implications for finanial crime, money laundering and tax evasion”

Sean Foley, Jonathan R.Karlsen, Talis J. Putnns, (2019) “Sex, drugs and bitcoin: How much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies?”.

ECB, (May 2019), Occasional Peper Series: “Crypto-assets: Implications for financial stability, monetary policy, and payments and markets infrastructures”

ECB opinion, of 19 February 2021, “On a proposal for a regulation on Markets in Crypto-assets, and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937”.

European Commission proposal for a “Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-asses, and amendind Directive (EU) 2019/1937”.

ECB, “Report on a digital euro”, (October 2020)

FSB, (October 2018), “Crypto-asset markets: Potential channels for future financial stability implications”

FSB, (May 2019), “Work underway, regulatory approaches and potential gaps”

Judith Arnal Martín, María Eugenia Menéndez-Morán and Javier Muñoz Moldes.

Technical and Financial Analysis Office of the General Secretariat of the Spanish Treasury, Ministry of Finance and Digital Transformation.

1 Sean Foley, Jonathan R.Karlsen, Talis J. Putnns, (2019) “Sex, drugs and bitcoin: How much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies?”

2 Stablecoins: Implications for monetary policy, financial stability, market infrastructure and payments, and banking supervision in the euro area. Occasional Paper Series, ECB Crypto-Assets Task Force.

3 Within the co-decision process, parallel negotiations are taking place at the European Parliament. This article covers exclusively the Council negotiations where the authors are representing Spain.

Stock and Crypto Market Values. Photo: Maxim Hopman (@nampoh)