Theme

This paper aims to compare the socio-economic trends of Spain and Portugal. Eventually the goal is to determine the alleged soundness of Portugal’s performance.

Summary

Spain and Portugal have been the focus of international attention due to their respective economic recoveries in recent years, coming from very difficult economic times. Both were, along with Greece and Italy, among the EU nations most affected by the 2008 crisis, suffering from economic contraction, high levels of unemployment, internal and external indebtedness, wide public deficits and, in the case of Spain, a gigantic real-estate bubble. Nevertheless, and despite the countries’ achievements in sorting out their economic woes, Portugal’s improvement is seen as miraculous, while Spanish achievements are somewhat undervalued. The question now is to elucidate if these arguments are well substantiated and analyse the demographic and economic foundations of both countries. As John Adams wrote in 1770, ‘facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence’. So let us find out.

Analysis

A long time has passed since Portugal and Spain, the two neighbours of the Iberian Peninsula, stood out along with Greece and Ireland as the worst performers of the EU, the so-called PIGS –a nasty, derogatory acronym to describe the economies of these countries during the financial crisis–. Things have changed notably since then.

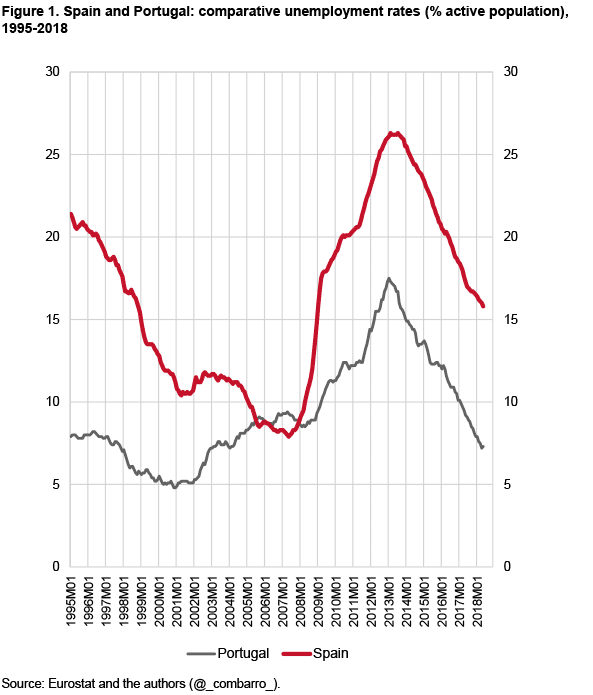

Portugal is now often cited as an example of economic resurgence, applauded by international institutions. Most of the praise is based on the good behaviour of its unemployment rate. To put the claim in perspective, as shown in Figure 1, Spain and Portugal had similar unemployment rates at the end of the previous expansive cycle. Since then, the Spanish rate skyrocketed to the historical figure of 26.3% in mid-2013, while Portuguese unemployment rose to 17.5% during the same period. Here, the impact of the Spanish real-estate bubble is evident, as we will see later in this analysis. From 2013 on, both rates followed parallel courses, dropping to 15.9% in Spain (10.4 percentage points down) and to 7.4% in Portugal (down 10.1 pp). The main difference is that Portuguese unemployment levels are currently below those of 2008, whereas Spain’s are still far above them.

Both countries are recovering from very hard times. Seven years ago, Portugal needed a bailout of €78 billion (US$92.2 billion) from EU institutions and the International Monetary Fund. After many economic and fiscal reforms, led by a centre-right coalition government under the supervision of the IMF and the EU, Portugal freed itself from international assistance in June 2014. Since then, the Portuguese economy’s pace picked up. The country also managed to exit the eurozone’s ‘excessive deficit procedure’ in 2017.

In Spain things have also substantially improved. Over the past few months, the rating agencies Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s and Fitch have all upgraded Spanish sovereign debt ratings. It appears that the country’s economy is on a robust but more resilient course than in previous expansions. This is reflected in its improved growth forecasts for 2018 and 2019, both from the IMF and the EU Commission. The days of astonishingly painful levels of unemployment (which peaked at 26%) and huge fiscal deficits (topped at 11% of GDP) now seem far behind.

Despite these apparent similarities in both countries’ recent achievements, there seems to be a consensus, especially among progressive media and analysts, to refer to Portugal’s improvement as a kind of ‘miracle’ while somewhat undervaluing Spanish achievements. The current Portuguese socialist government, in power since October 2015 and backed by two far-left parties in parliament, argues that its anti-austerity strategy, which included rolling back pension and salary cuts, is behind the country’s good performance. The popularity achieved due to these measures by its former Finance Minister Mario Centeno, a Harvard-educated economist, helped him to win the race to become President of the Eurogroup, one of the eurozone’s most important policymaking posts.

At this point, some questions come to mind. Are all these claims fair and well substantiated? Is Portuguese economic growth as robust and sustainable as alleged? Moreover, are Portuguese and Spanish socio-economic foundations and models similar? What about their respective weaknesses? Doing a similar exercise as that developed for Italy and Spain, we now aim to compare the socio-economic trends of the two Iberian countries. Eventually our goal is to find out whether Portugal’s performance is structural or merely temporary.

Demographics

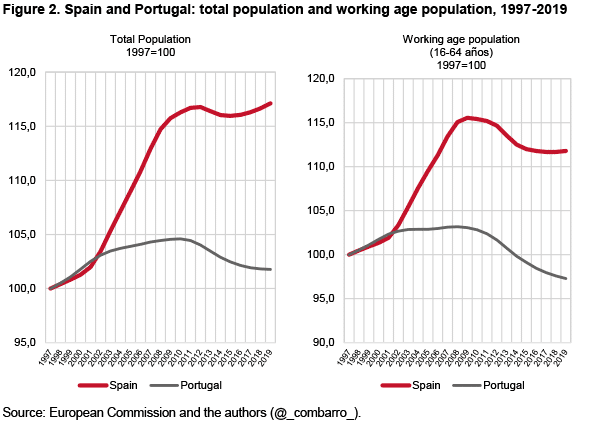

We can undoubtedly affirm that demography is one of the most serious issues in Portugal. As reflected by the British Centre for Policy studies, in recent years EU members have experienced similar demographic trends: a declining fertility rate, an aging population and slowing rates of population growth. But amongst Western European countries, Portugal stands out. Its rate of population growth has dropped quickly in recent years and it currently has one of the fastest declining populations in Europe. Spain, although showing similar overall trends, has a more robust demographic foundation than Portugal thanks to immigration. The Portuguese net migration rate has been negative since 2011 and the country has not benefited from any immigration boom, while Spain ranked second in the list of the top-10 world nations with the highest levels of net migration between 2000 and 2010, according to the UN. Moreover, after a parenthesis of negative net migration rates between 2011 and 2015, Spain has come back to positive population inflows. Figure 2 shows the impact of this phenomenon.

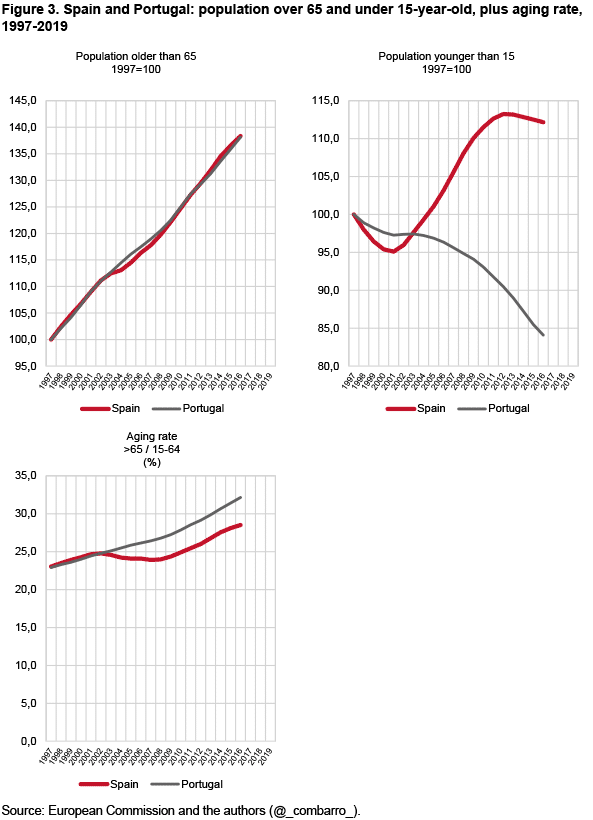

Although the increase in the population aged over 65 is growing at the same pace in both countries, net migration helped Spain refresh its demographic base with young people, and that also impacted on the overall ageing rate, as shown in Figure 3.

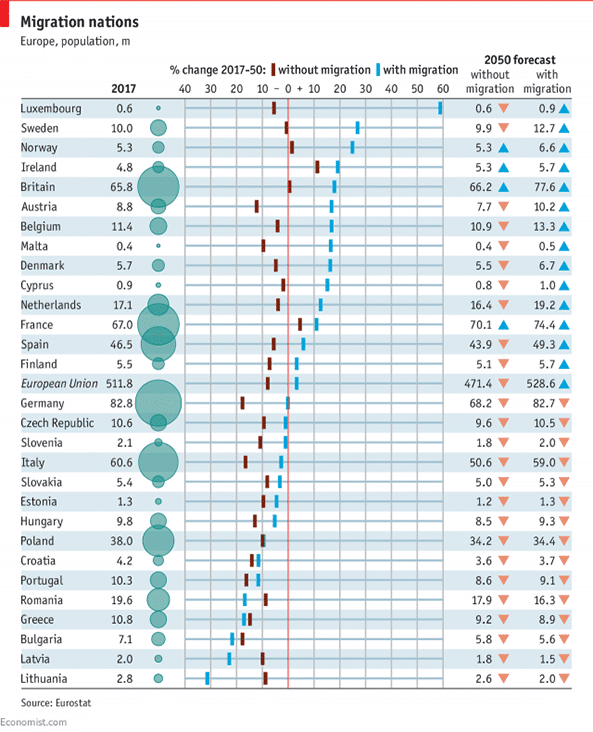

According to the European Commission, the demographic forecasts are not favourable for either countries, but the Portuguese situation is clearly worse. Figure 4 shows how net migration at current levels is unlikely to prevent Portugal from shrinking. In the mid-term, to assure sustainable growth, the country will urgently need to attract and retain new people, which ultimately means new workers, or increase its birth rate or learn to live with a declining population. A challenging task.

Employment

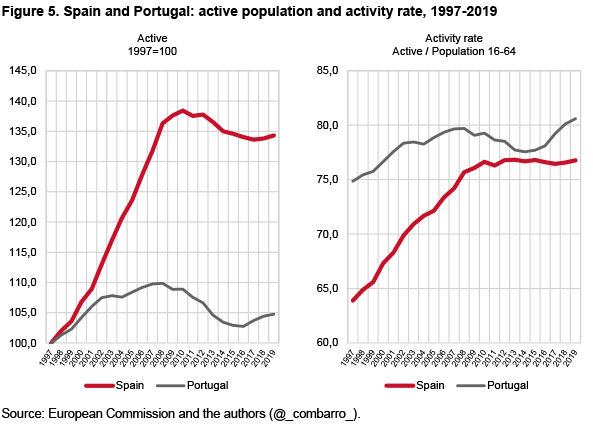

The Spanish economy, unlike the Portuguese, experienced big structural changes in the job market over the past decade, fueled by the immigration boom of the 2000s and the increasing female labour-force participation rate, which in 2013 practically reached Portuguese levels. That marked the huge difference in the active population shown in Figure 5, which in Spain rose by 40% between 1997 and 2008, compared with a modest 10% in Portugal.

During the expansive phase of its economy, up to 2008, and despite its population growth, Spain generated 45% of the additional employment existing in 1997, while in Portugal the increase was only 10%. As shown in Figure 5, the Spanish employment rate gradually converged with the Portuguese, from a 15-percentage point difference to less than 5pp. The big crisis abruptly broke this trend in both countries, most significantly in Spain, due to the bursting of its gigantic real-estate bubble, something that did not occur in Portugal. After a swift deterioration, the gap between the two countries has remained stable.

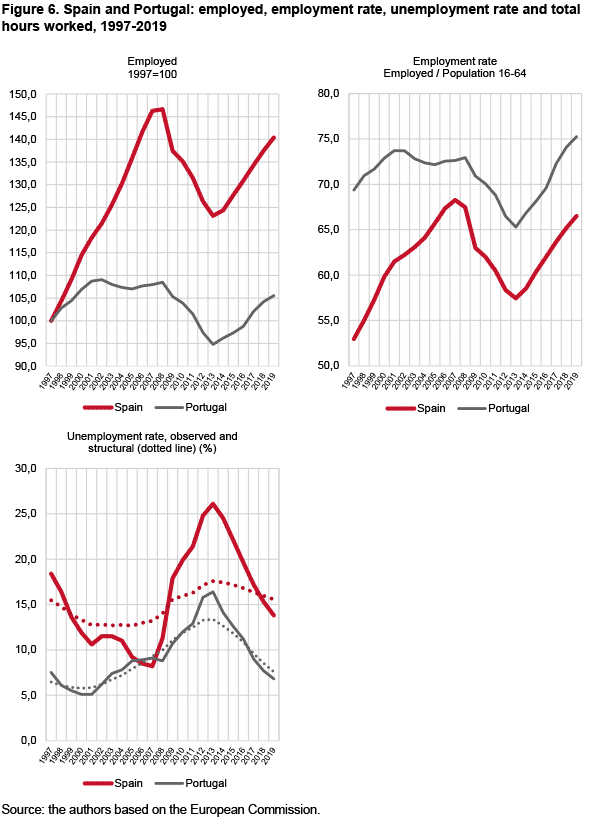

The number of employed and employment and unemployment rates (Figure 6) provide a good general comparative picture of the respective labour markets. A notable feature is the structural nature of the higher unemployment figures in Spain, as well as its deeper and longer fall in overall employment during the recession. During the recovery, both countries grew steadily, with 2017 being an especially vigorous year for Portugal.

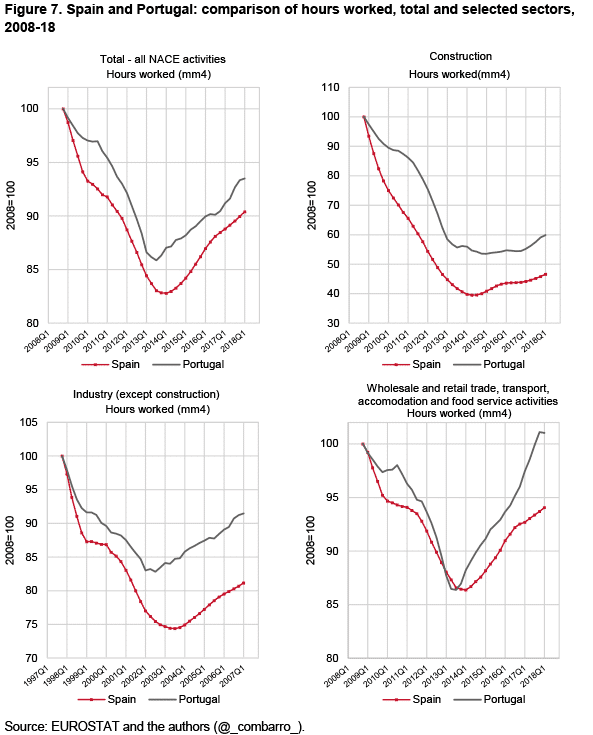

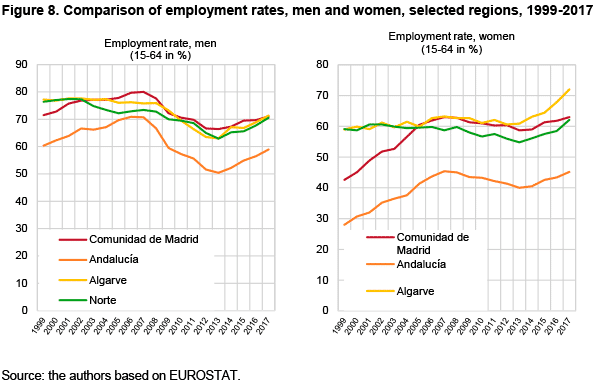

To better understand the labour market differences between the two countries, a sectoral analysis is necessary. Figure 7 shows the abrupt Spanish drop in industry and construction during the crisis, coherent with the bursting of the real-estate bubble. Nevertheless, the key factor that elucidates the extraordinary evolution of employment indicators in Portugal is the growth of hours worked in wholesale and retail trade, transport, accommodation and food service activities, directly linked to tourism, as mentioned in the introduction to this paper. Here, the Portuguese figures rocketed in 2017, compared with a more modest growth in Spain. This also explains that the most dynamic region regarding employment growth is currently the tourist-based Algarve, which has clearly overtaken central Portugal (as shown in Figure 8). Additionally, the female labour force is primarily responsible for the increase.

In addition, another key structural difference between the Portuguese and Spanish labour markets should not be ignored: the regional setup. Portugal has a homogeneous labour distribution throughout its territory, with similar male and female employment rates in the different regions. On the contrary, in Spain, the regional contrasts are very noticeable. Figure 8 shows a comparison of employment rates between Madrid and Andalusia in Spain, on the one hand, and those of the Algarve and northern Portugal, on the other. Again, it is useful to note the sharp increase of the female employment rate in the Algarve tourist region.

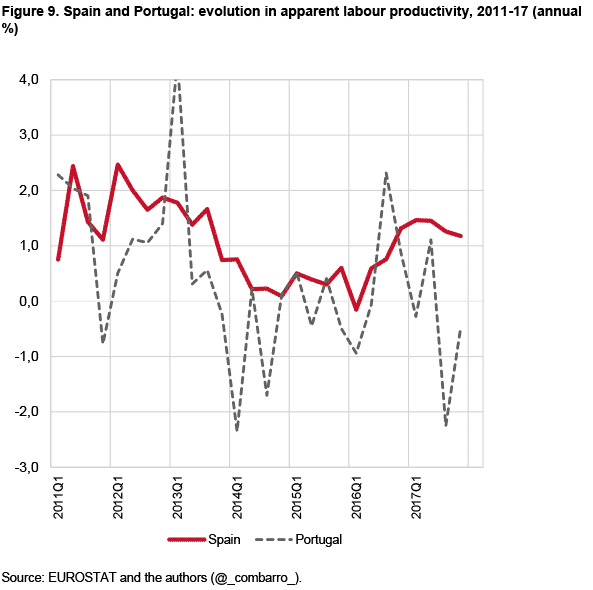

In summary, the sharp rise in Portuguese employment and its activity rate during 2017 was sustained by tourist areas and by increased female participation. Nevertheless, this noticeable job creation (3.3%) was only partially reflected in the overall GDP (2.7%), which means a negative apparent productivity of labour (Figure 9). This implies that despite wage moderation, unit labour costs in Portugal are rising and it could involve a gradual loss of competitiveness, at least relative to Spain and to other members of the common currency area. The data also indicate the exceptionality of the country’s employment figures in 2017, something already pointed out by the European Commission in its 2018 and 2019 forecasts.

GDP and growth

The eurozone grew at its fastest rate in a decade in 2017, with a gross domestic product expansion of 2.3%. Both Spain and Portugal stood out in this area. Spanish GDP growth remained strong in 2017, at 3.1%, above the euro area average for the third year running. For its part, Portuguese economic growth picked up to 2.7% in 2017, as mentioned above. Nevertheless, the size and structure of both economies are notably different.

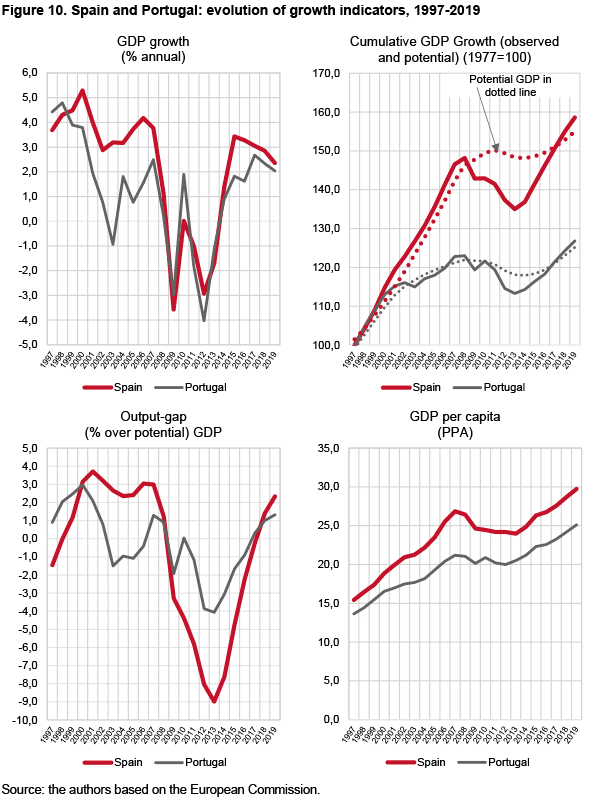

Spain is, according to the most recent FMI estimates, the 15th largest world economy (in PPP terms), with Portugal 55th. In terms of per capita GDP (PPP) the gap is smaller, with Spain ranking 32nd and its neighbour 43rd. If we go beyond the GDP for comparison, using the Human Development Index, Spain and Portugal are placed 27th and 41st, respectively. Figure 10 shows the comparative evolution of the main growth indicators, reflecting the Spanish boom of the 2000s and the deeper impact of its crisis. After the recovery, both countries are growing above their potential GDPs, outperforming expectations.

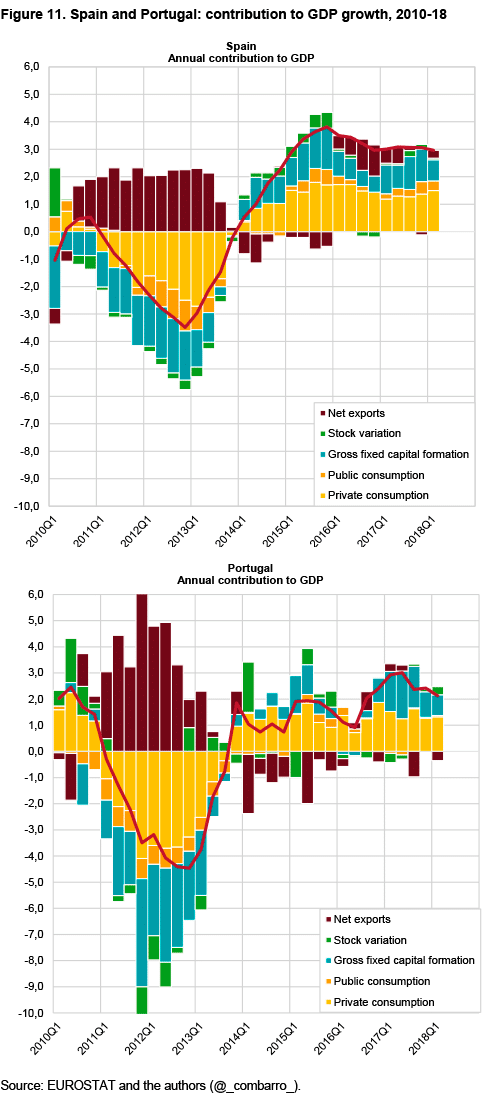

Figure 11 helps to better compare the differences in GDP growth and the contributions in each country. Private consumption, net investment and sound exports have been the main drivers of the Spanish economic growth model these past years, also with an important role for the public sector, which is now starting to grow. Portugal has a less diversified economy, something that the new progressive government wants to improve through a pragmatic approach. In fact, it has followed many of the economic guidelines set by its conservative predecessor, setting up an intensive National Reform Programme to have a more dynamic economy that is attractive to investment and starting to show its effects. Domestic demand (supported by job creation, wage growth and favourable financing conditions) is strong and tourism remains a major driver, as explained above (accounting for 11% of Portuguese GDP and 8% of employment). Investment growth rose thanks to an upturn in construction and equipment. A recent capacity expansion in the automotive sector is projected to provide a more robust framework.

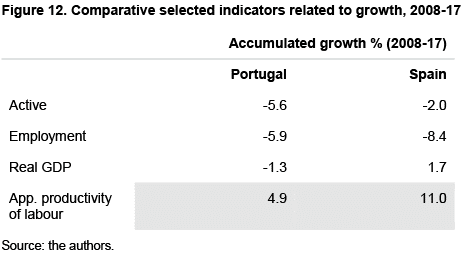

Figure 12 summarises the accumulated growth in active population, employment and real GDP from 2008 to 2017, as well as the resulting growth in the apparent productivity of labour. The large decline in Portugal’s active population has been a key contributor to the reduction in the country’s unemployment rate. Moreover, the overall growth in the apparent productivity of labour was significantly lower in Portugal than in Spain. Both indicators (lower active population growth plus lower productivity) will have negative effects for Portugal in the mid-term, even though in the short term they apparently favour a reduction in the unemployment rate.

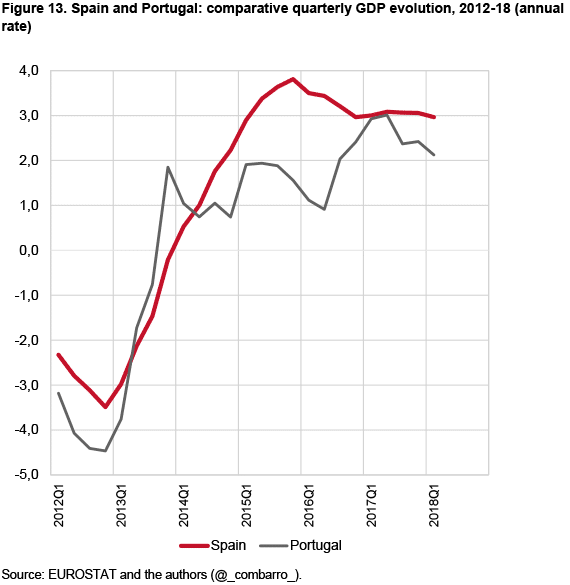

Finally, focusing only on the past two years, despite Portugal’s exceptional achievements, its economic growth has been lower than Spain’s, as shown in Figure 13.

Wage, salaries and productivity

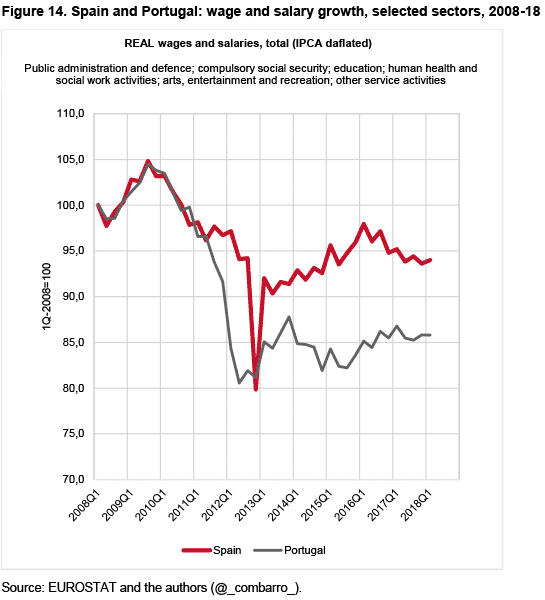

At this stage, mention should be made of the severe adjustments undertaken in the Portuguese public sector as a result of the reformist agenda that accompanied the country’s bailout. Public financial management has been substantially improved, the receipts from an ambitious privatisation agenda exceeded the initial Programme target, a significant reduction in public administration staff numbers was achieved, including through early retirement and mutually-agreed contract termination, while several attempts by the government to reduce public-sector wages were mostly ruled unconstitutional. These adjustments in the public sector are shown in Figure 14. Wages are projected to gradually grow over 2018-19 along with the unfreezing of career advancement in the public sector.

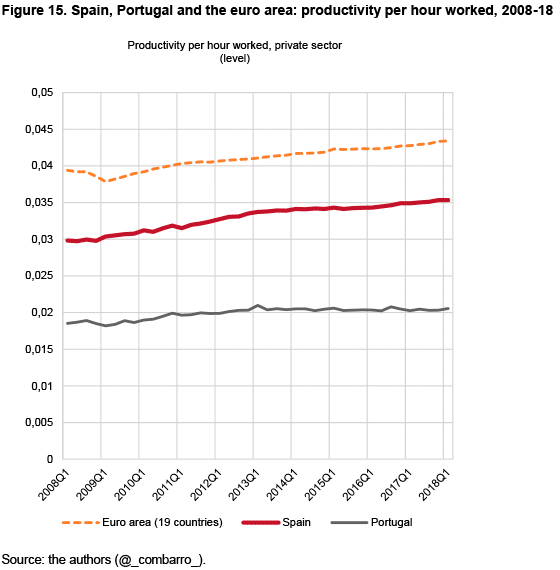

Regarding productivity, as shown in Figure 15, there is a clear divergence between Portugal and both Spain and the euro area average. The trend is even clearer if considering Portuguese productivity in reference to the entire EU, which has been consistently declining since 2013. Portugal is experiencing a greater slowdown in productivity growth than in advanced economies. The rising and deeper integration of the Portuguese economy in global markets in recent years was expected to lead to a convergence in productivity, but this is not occurring. A very interesting paper by Ricardo Pinheiro Alves, of the Gabinete de Estratégia e Estudos of the Portuguese Ministry of Economy, concludes that the increasing misallocation of capital, labour and skills both at a sectoral and business level are behind this productivity issue. Additionally, we believe that the rapid growth in employment in the tourist sector, as well as the relative importance of agriculture in Portugal, also weigh on these poor results.

In contrast, Spanish productivity has increased steadily over the crisis. Most of the adjustment from 2008 to 2011 came from job destruction, but since then there are two factors that have contributed to productivity growth: (1) the strong recovery in exports, with a fair product diversification; and (2) the effects of labour market reform. On the other hand, there are still elements that prevent productivity from growing more markedly: the overreliance on temporary workers (much more pronounced in Spain than in Portugal); persistent rigidities in the wage setting system; a high concentration of export firms, leading to a lack of competition; and the small size (and consequently, low productivity) of Spanish companies, which account for a large part of employment and output. The latter is also a Portuguese feature.

Trade

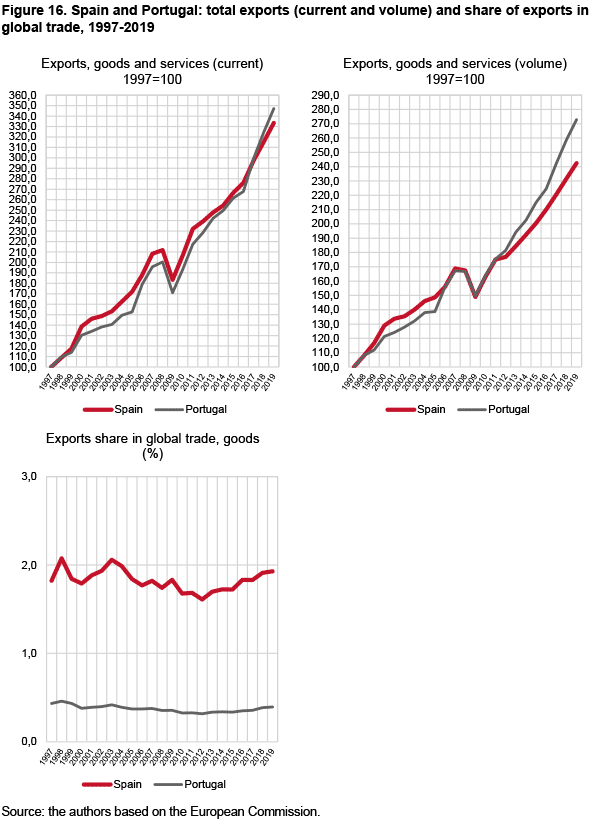

According to the World Trade Statistical Review 2017, Spain ranks 16th in the world ranking of merchandise exporters and 11th in commercial services, while Portugal is 47th and 35th, respectively.

Both the Portuguese and Spanish foreign sectors have been gaining importance in recent years. Between 2005 and 2017 Portuguese exports increased their share of GDP by 16 percentage points in nominal terms, and now account for more than 40% of GDP. Exports have, along with tourism, been the key element in the recovery of the Portuguese economy. The dependence of Portuguese exports on European countries has decreased from 80.3% of total exports of goods in 2005 to 73% in 2017, bringing more robustness and diversification. Exports outside the EU increased their share from 19.7% in 2005 to 26.8% in 2017, with the US being Portugal’s biggest non-European trading partner. Brazil and Angola, as former Portuguese colonies, are also important destinations. According to Caixabank Research, part of the increase in Portugal’s trading volume in recent years can be explained by its greater participation in global production chains, with an increasing demand for Portuguese products in the countries of the ASEAN bloc, China and India.

Regarding Spain, as explained in the Elcano Expert Comment 16/2018, Spain’s exporting strength continued in 2017 when sales of goods abroad increased for the eighth consecutive year and reached a new record of €277.1 billion, close to one quarter of GDP. External demand has been largely responsible for Spain’s recovery. Spanish exports are less dependent on the country’s EU partners than Portugal (65.7% of the total). The increased geographical diversification of exports has helped to boost sales in relatively new markets such as China and Turkey. The leading export sectors were capital goods (20.3% of the total and up 9.2%), food, drinks and tobacco (16.5% and 6.3%, respectively) and the motor industry (16.3% and 0.1%). Spanish exports are expected to grow strongly in 2018 and 2019, as Spain continues to register small gains in market share despite the projected appreciation of the euro.

When it comes to bilateral trade, Spain has been increasing its share in Portuguese imports (from 27% in 2012 to 33% in 2016), whereas the Portuguese share of the Spanish market remained relatively stable at around 3.9%-4%. According to the latest official statistics, figures on bilateral trade between January and December 2017 show a year-on-year increase in Spanish exports to Portugal of 10.1% (€19.844 million). Spanish imports from Portugal amounted to €11.001 million, a year-on-year increase of 0.9%.

Debt and deficit

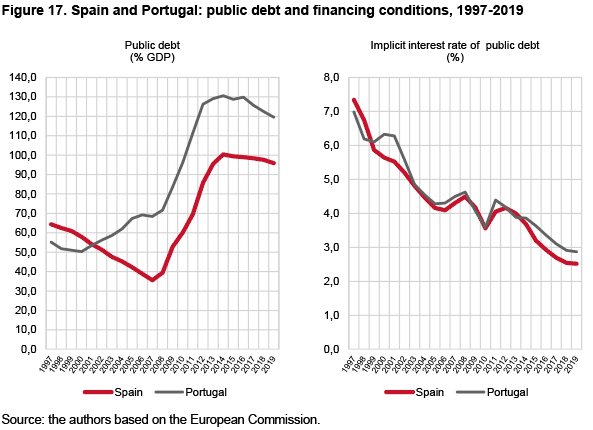

High gross public debt-to-GDP ratios have been one of the main economic Portuguese woes during the crisis, but after falling by 4.2 pp to 125.7% in 2017, they are forecasted to decline further to 122.5% in 2018 and 119.5% in 2019, mainly due to fiscal adjustments and economic growth (Figure 17). By contrast, the Spanish public-debt ratio recently stabilised at around 100% of GDP and is also experiencing a reduction.

Regarding private debt, Portugal still has to deal with a high level of bad loans in the banking system (16.7%, while the figure is 4.8% in Spain) and substantial consolidated private sector debt (163.5%, compared with 139.2% in Spain, according to Eurostat). In this regard, Portugal remains more vulnerable to macroeconomic downturns than its neighbour. Here it is important to highlight that both countries benefit greatly from the favourable financing conditions set by the European Central Bank’s monetary policy in recent years.

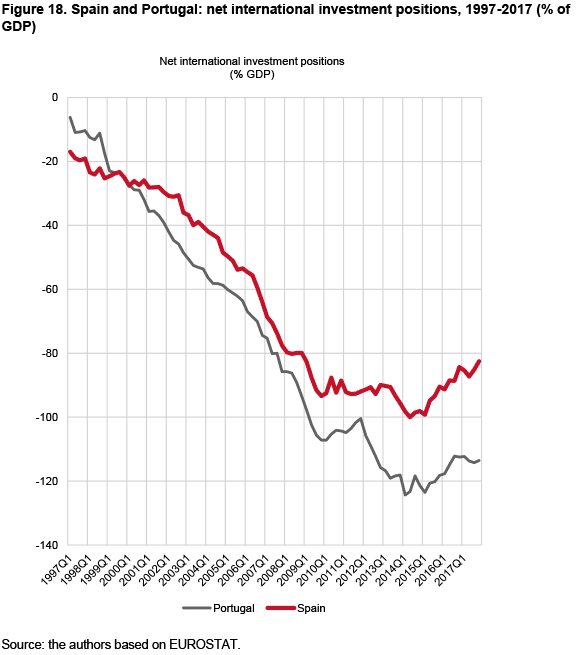

Net international investment position

The comparison in this area shows similar patterns but still a significant difference between the two countries. Portugal is more indebted to the world than Spain. Since the introduction of the euro, both countries’ net foreign assets declined, but Spain has finally managed to reduce its large current-account deficit to a greater extent than Portugal and has recently shifted to external surpluses, which has been sufficient to stabilise and slowly reduce its net external indebtedness. The recovery in Portugal appears clearly weaker in this area.

Conclusions

The facts and figures analysed so far speak for themselves. Our key findings shows that:

- Portugal has a much severe demographic problem than Spain, with no sign of improvement. This weighs heavily on its economic future, as the country needs to reduce emigration and at the same time encourage the growth of businesses with limited resources. Lowering the barriers for the immigration of non-EU workers and investing in human capital will be the only viable ways to improve.

- The apparent productivity of labour in Portugal is much lower than in Spain and has been declining over time. This implies a gradual lose of competitiveness, both relative to Spain and to other members of the eurozone.

- The main driver of Portuguese employment growth is tourism. The tourism boom has made the industry one of the biggest contributors to the national economy and is now its largest employer, with female labour-force participation playing a key role in the take-off. Spain’s labour framework remains more diversified.

- The three factors above, although fostering a rapid improvement in the Portuguese economy, are not sustainable over time, reducing the country’s growth prospects in the mid-term.

- Despite its very noticeable economic developments, both public and external debt place the Portuguese economy in a more vulnerable situation than Spain’s.

In summary, even though Portugal has achieved substantinal progress over the past few years, returning to economic growth and budgetary stability (thanks to a severe, partially imposed, plan of reforms), which has been enthusiasticaly called ‘the Portuguese miracle’, seems to have been mainly the result of a temporary rise in tourism but resting on a very negative demographic base combined with low productivity. This reduces the apparent unemployment rate but makes mid-term economic expectations worse. Such a lack of sustainability, along with public and private debt issues, are a cause of reasonable concern.

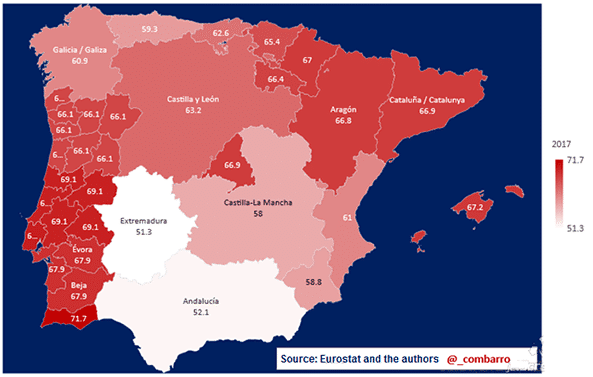

Spain, on the other hand, shows a better macroeconomic position overall and its macroeconomic improvements deserve greater recognition, although this should not lead in any case to self infulgence and conformism. Further changes are needed in the labour market, fiscal system and regional financing. The sustained growth and employment recovery of recent years should be reflected in increasing wages in the private sector and better opportunities for both young people and the more disadvantaged social groups. In this regard, and due to its territorial configuration, Spain lacks Portugal’s market and administrative uniformity, making the implementation of reforms more difficult and increasing regional disparities. Figure 19 perfectly summarises the situation. In a country where territorial administrations manage around 50% of public expenditure and account for 77% of public employees, administrative standardisation, coordination and simplification are essential to prosper and compete in the global arena.

Sebastián Puig

Analyst, European External Action Service | @Lentejitas

Ángel Sánchez

Professor of Macroeconomics, UNED