Theme

Between the end of June and the first half of July the Argentine government launched Phase 2 of its Stabilisation Plan, doubling down with a severe monetary tightening to lower the price of the parallel dollar and reduce the gap with the official dollar, bring forward the removal of exchange rate controls and accelerate the decline of inflation. What is the future of the Stabilisation Plan if the government succeeds in quickly achieving its proposed objectives and what options are available if it does not?

Summary

With the launch of Phase 2 of the Stabilisation Plan, the government displays consistency with the stabilisation strategy it has pursued so far, relying on the fiscal surplus and strong monetary tightening to steer it to success. The goal: to persuade the market that there will be no step devaluation of the official dollar and, if successful, trigger the sale of dollars, convergence of the parallel dollar with the official dollar (from the parallel towards the official), unification of the foreign exchange market and lifting of exchange rate controls, capital inflows for strategic investments, an increase in international reserves, reduction of country risk and the recovery (and remonetisation) of the economy.

Can the zero deficit-zero monetary expansion-2% devaluation programme achieve its goals? Certainly, it can. But if Phase 2 of the plan does not work as expected and the market is not convinced that the current trajectory of the official exchange rate is sustainable, the exchange rate gap does not close by the necessary magnitude or speed needed to lift exchange rate control, country risk does not ease, the government may opt to rectify the exchange rate path flexibly by devaluing the official dollar to unify it with the parallel dollar -from the official towards the parallel-, consider simultaneously lifting exchange rate controls and ensure a unified exchange rate trajectory consistent with an increase in international reserves, to lower country risk and facilitate an economic recovery while shielding fiscal balance and monetary tightening.

Doing this effectively and in time (to avoid weakening the political capital and social tolerance for fiscal adjustment, which could compromise the fiscal balance) will require the ability to quickly adapt to circumstances and surgical precision to do what is necessary without destabilising inflation and exchange rate expectations. One way to mitigate these risks is to secure a new agreement with the IMF that helps to shield the programme and to control expectations (it would be incomprehensible if, in such a scenario, the IMF did not grant Argentina a new programme). All of this is within reach of an economic team that, under enormously complex circumstances, has operated so far with skill, pragmatism and determination.

This framework of uncertainty explains why the government has wisely chosen to maintain its programme in Phase 2, then evaluate the results. With those results in hand, it can confirm or modify the course, making that decision once the necessary information is revealed to determine whether it is a matter of aligning market expectations with those of the economic programme, as the government believes (virtuous scenario), or if there is an underlying factor that needs adjustment, such as the exchange rate trajectory (scenario with adjustments), as the market seems to believe at the moment.

In formulating economic policy, policy makers cannot afford to swing wildly at the slightest obstacle. Persistence is not always synonymous with stubbornness or dogmatism but the optimal response when decisions must be made with imperfect information and uncertainty about the underlying reality in which economic policy operates and, in a context, where expectations can easily become unanchored.

Analysis[1]

Between the end of June and the first half of July, the Argentine government launched Phase 2 of the Stabilisation Plan doubling down with a severe monetary tightening, to lower the price of the parallel dollar, reduce the gap with the official dollar, bring forward the lifting of exchange rate controls and accelerate the decline in inflation.

To achieve this, the government announced the closure of all remaining sources of monetary issuance: the elimination of the Central Bank’s interest-bearing liabilities -IBLs- and their transfer to the Treasury; the exchange of the Central Bank’s contingent liabilities with the financial system -puts on Treasury securities-; and the end of net dollar purchases in the foreign exchange market. The monetary financing of the non-financial public sector (NFPS) had already been closed in Phase 1 of the programme, as Argentina registered a fiscal surplus in the first half of the year.

The government has placed all bets on deepening its initial plan without raising the anchor, ie, maintaining the trajectory of the official exchange rate at a depreciation rate of 2% per month and planning to lift exchange rate controls when it can be done without creating instability.

Can the zero fiscal deficit-zero monetary expansion-2% devaluation programme achieve its goals? Certainly, it can. But if not, the government can opt to rectify the course quickly and flexibly. There is still time, but it is a race against time if the formidable macroeconomic achievements of Phase 1 of the plan are to be preserved and enhanced. It is fair to recognise that these were achieved with enormous sacrifices from the population who saw their incomes drop significantly.

In the following analysis, we will: (a) review Phase 1 of the Stabilisation Plan and its achievements; (b) the rationale for Phase 2 of the plan; (c) the pillars of Phase 2 of the Stabilisation Plan; and (d) the future of the Stabilisation Plan if the government succeeds in quickly achieving its goals and the options available if it does not.

1. Stabilisation Plan: Phase 1[2]

Phase 1 of President Javier Milei’s Stabilisation Plan began a few days after taking office on 10 December 2023. The essential ingredients were:

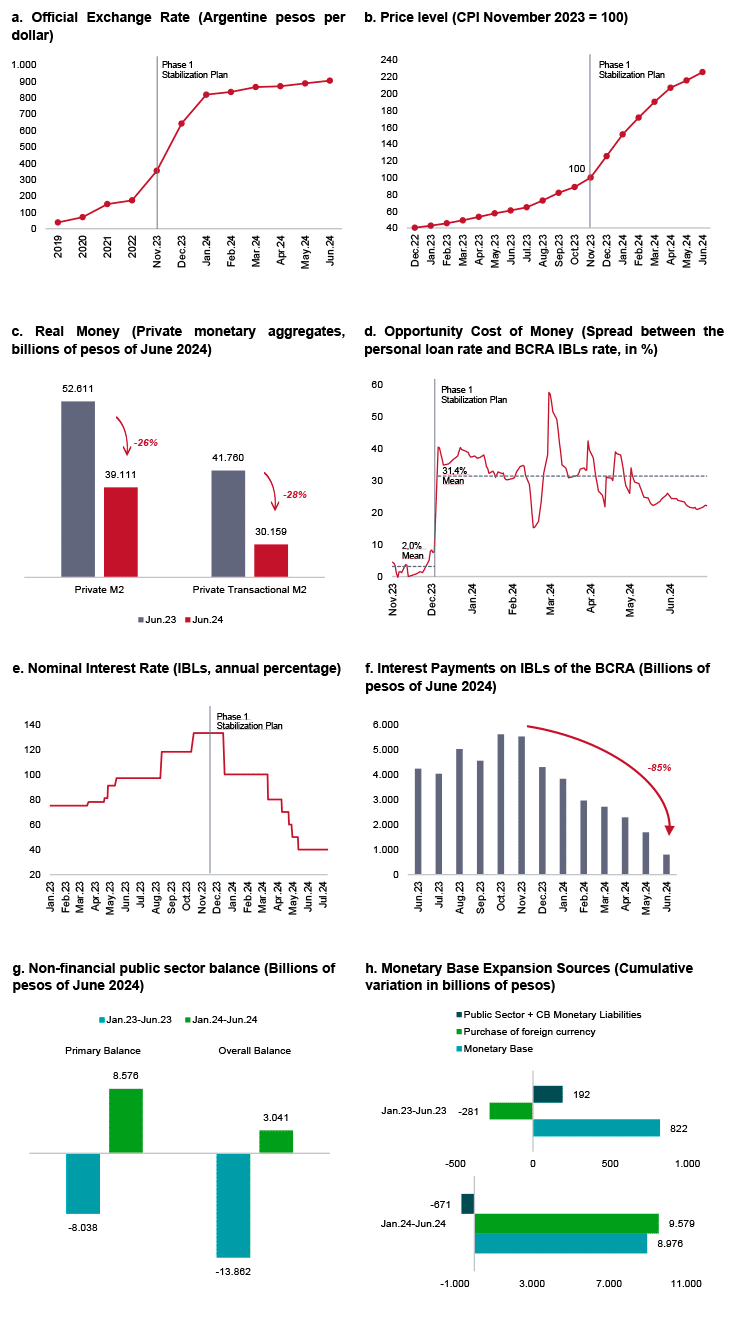

- Dilution and stabilisation. Devaluation of the official exchange rate by 100% (with simultaneous adjustment of public utility prices and liberalisation of controlled prices); a surge in the price level (the CPI doubled in just five months); stabilisation using the official exchange rate as the nominal anchor (pre-announced devaluation of 2% per month), preservation of exchange rate controls, known as the cepo in Argentina (which, for practical purposes, partially plays the role of international reserves that the Central Bank lacks to fix the exchange rate at the set rate) (see Figures 1.a and 1.b).

- Severe monetary contraction. The jump in the price level drastically reduced the real quantity of money, generating severe illiquidity (see Figure 1.c). This illiquidity can be observed in the dramatic jump in the spread between the interest rate banks charge for personal loans and the rate of the Central Bank’s interest-bearing liabilities (IBLs). The spread, which measures the opportunity cost of holding liquid money, went from an average of 2 percentage points (200 basis points) in November 2023 to an average of 30 percentage points (3000 basis points) between December and June 2024 (see Figure 1.d).

The severe contraction of peso liquidity not only led markets to sell dollars to the Central Bank to acquire pesos but also allowed the Central Bank to issue (it’s now scarce and revalued) peso liquidity at substantially lower rates.

- Drastic reduction of interest rates on the Central Bank’s interest-bearing liabilities and interest payments on these liabilities (see Figures 1.e and 1.f).

- Severe fiscal adjustment. The turnaround of the non-financial public sector (NFPS) balance was 5.5% of GDP and was achieved in record time. The jump in the price level enabled a real reduction in primary spending of more than 30% and the achievement of a primary surplus in the first half of the year (see Figure 1.g).

- Monetary issuance only for dollar purchases. The combination of contractionary fiscal and monetary policy meant that in the first half of the year, the Central Bank only issued money to buy dollars. This was because it was not necessary to issue money to finance the NFPS due to the fiscal surplus and because the Central Bank absorbed pesos.

The results were immediate:

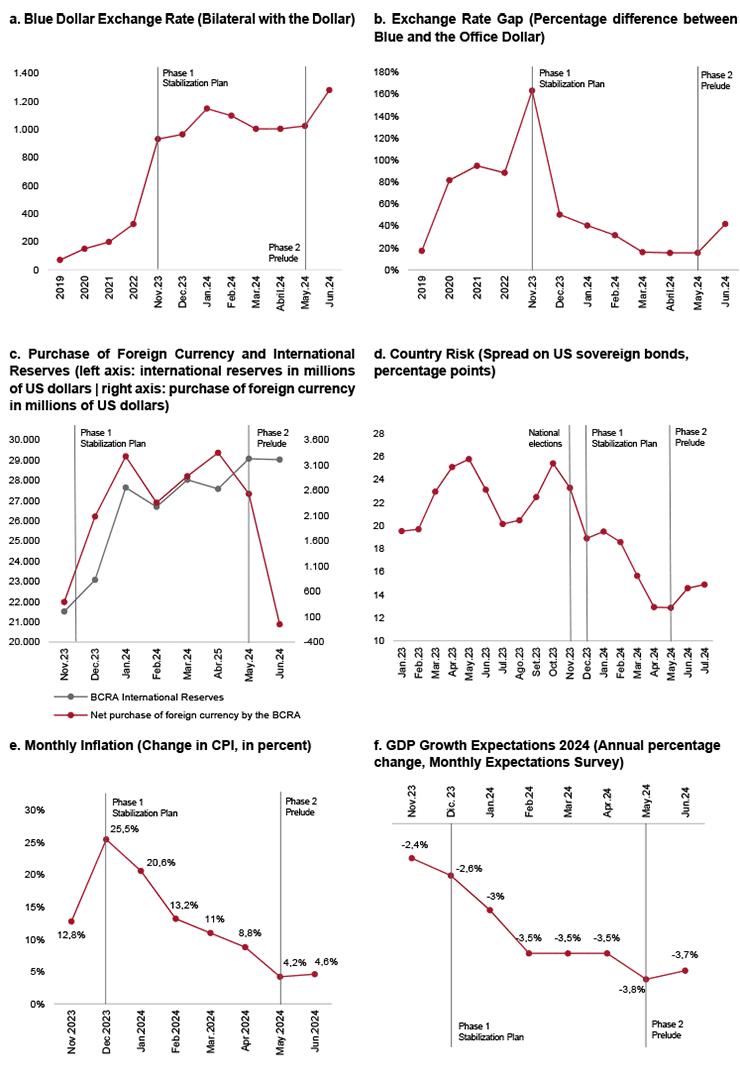

- The parallel dollar stabilised and the gap with the official dollar declined sharply (see Figures 2.a and 2.b).

- The Central Bank’s dollar purchases increased, international reserves grew and country risk declined (see Figures 2.c and 2.d).

- Inflation decreased significantly at a much faster rate than the market expected, and the economy experienced a sharp economic contraction (see Figures 2.e and 2.f).

Figure 1. Pillars of the Stabilisation Plan: Phase 1

Figure 2. Macroeconomic performance during Phase 1 of the Stabilisation Plan

2. Phase 2: prelude

Despite the initial success of the programme, a significant divergence remains between:

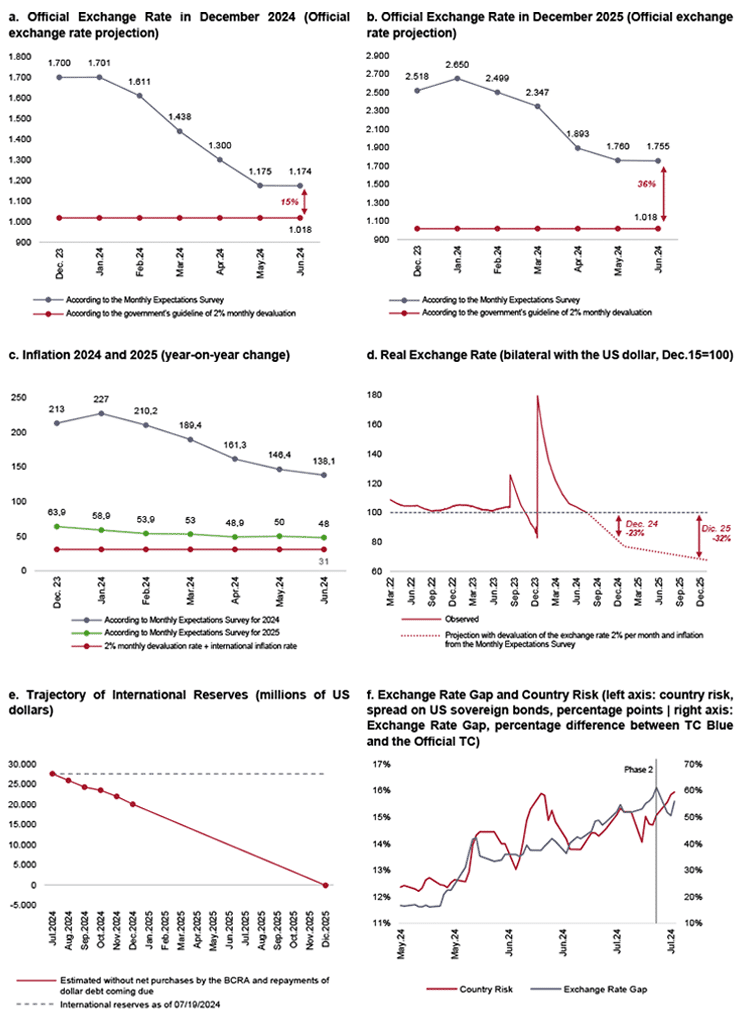

- The trajectory of the official exchange rate expected by the market and that implied by the 2% monthly devaluation rate announced by the government (see Figures 3.a and 3.b).

- The inflation expected by the market and that implied by the government’s programme (2% monthly devaluation plus international inflation), (see Figure 3.c).

- The trajectory of the real exchange rate (resulting from a 2% monthly devaluation and an inflation rate that is expected to be persistently higher than the devaluation rate ) and the trajectory that the market interprets as necessary to accumulate the international reserves Argentina needs to lift exchange rate controls, lower country risk, recover international credit, encourage capital inflows for investments in strategic sectors and enable economic recovery and a new agreement with the IMF (see Figures 3.d, 3.e, 3.f).

Aligning market expectations with the official programme on these three key variables (exchange rate, inflation and international reserves) was the key rationale for the government to go on the offensive by announcing Phase 2 of the Stabilisation Programme.

Figure 3. Phase 2 Prelude: government guidelines and market expectations

3. Phase 2: the pillars

The essential ingredients of Phase 2 of the Stabilisation Plan are as follows:

- Reaffirmation of the commitment to fiscal balance achieved in Phase 1.

- Continuation of the 2% monthly devaluation rate and exchange rate controls (which the government intends to lift as soon as circumstances allow it to be done smoothly).

- Closure of all sources of monetary issuance by the Central Bank (BCRA):

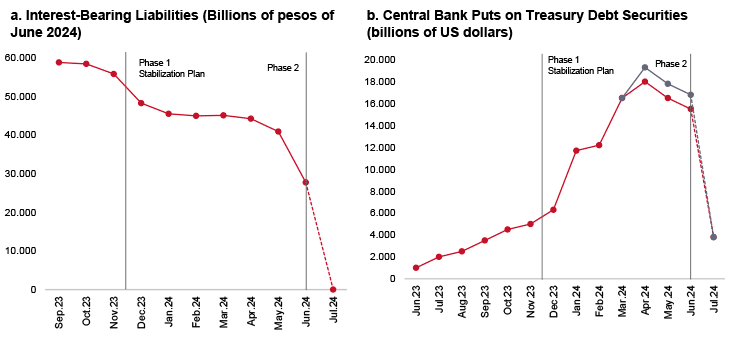

- Elimination of interest-bearing liabilities (see Figure 4.a)

The BCRA’s interest-bearing liabilities were exchanged for Treasury Bills (LECAP and LeFi), transferring the responsibility for interest and principal payments to the National Treasury.

Regarding LEFI (Liquidity Fiscal Bills), financial institutions will have access to the BCRA’s window through which they can buy or sell LeFi daily to manage liquidity. The interest rate resulting from the daily auctions of LeFi will be the BCRA’s monetary policy reference rate.

The goal of this measure is to deactivate an automatic source of monetary expansion (interest payments on BCRA’s interest bearing liabilities) and restore the BCRA’s independence in setting the monetary policy rate.

The transfer of interest payments from the BCRA to the Treasury will amount to about 0.5% of GDP, requiring an additional fiscal tightening to cover these expenditures without monetary financing.

- Repurchase of Central Bank Puts (see Figure 4.b)

The CB puts held by the financial system were a Damocles sword over the BCRA’s monetary expansion. The holder of a put has the right (but not the obligation) to sell Treasury Bills to the BCRA at a predetermined price and within a specified period if their value falls below the contract price of the put.

A voluntary re-purchase allowed the BCRA to extinguish nearly 80% of the stock of puts. To understand the scale of the operation before the voluntary exchange, if all banks simultaneously exercised their right (which they could do at any time within the contract period), the BCRA would have had to issue an amount equivalent to the entire monetary base.

The fundamental objective of this measure was to deactivate this time bomb.

- Sterilisation of Dollar Purchases in the Foreign Exchange Market

The issuance of pesos by the BCRA for purchasing dollars in the official foreign exchange market will be sterilised by selling dollars at a higher price in the ‘Cash with Settlement’ (also called CCL) market (which has a similar price to the parallel dollar). The amount of dollars sold in the sterilisation operation will be less than the amount purchased, so marginally, the BCRA’s reserves will increase as a net result of its intervention in the foreign exchange market.

The objective of this measure is to ensure that the pesos issued by the BCRA to buy dollars in the official market do not flow into buying dollars in the parallel market, which would lead to an increase in the parallel exchange rate and of the gap between the parallel dollar and the official dollar.

Figure 4. Stabilisation Plan: Phase 2

The logic of this phase of the Stabilisation Plan is as follows: leveraging on the fiscal surplus and dismantling other sources of monetary expansion by the BCRA, the government aims to convince the market that there will be no step devaluation of the official dollar by freezing the issuance of pesos, making the peso a scarce asset, forcing the sale of dollars to meet liquidity needs in pesos and thereby achieving convergence between the parallel and official dollar (from above) and reducing the gap between them to a sufficiently low level to unify the foreign exchange market and eliminate the exchange rate controls.

Simultaneously, Phase 2 of the plan aims for the monetary tightening to prompt a rapid convergence of inflation to a level of 2.2% per month, consistent with the official dollar devaluation guideline plus international inflation.

4. The future of the Stabilisation Plan: three scenarios

The success of Phase 2 of the Stabilisation Plan relies on two fundamental pillars: the fiscal balance and the accumulation of international reserves (which Argentina needs and currently lacks). We identify two polar scenarios: one virtuous and the other complex with opposite outcomes. Additionally, there is a third scenario, which involves amendments to the original plan that could recover the virtuous scenario.

These scenarios result from analysing two opposing views on exchange rate policy: the one announced by the government and the one the market believes is necessary to sustain fiscal balance and international reserves accumulation.

One possible outcome is that the government, through its actions, ‘convinces’ the market that the current exchange rate policy is consistent with both objectives (virtuous scenario).

Another possible outcome is that the market believes the current exchange rate trajectory is inconsistent with these objectives and the government insists on maintaining its exchange rate policy (complex scenario).

Finally, if the government fails to convince the market that these objectives are achievable with the current exchange rate trajectory, it may choose to modify the exchange rate path (scenario with tunings).

The complexity and unusual nature of the current situation make it virtually impossible to know in advance which scenario will emerge. It depends on factors that are very difficult to measure, such as the private sector’s demand for liquidity in pesos during this transition phase and the corresponding need to sell dollars as the government reduces liquidity in pesos.

In this uncertain context, any of the three scenarios is possible. However, clearly, the scenario with tunings dominates the complex scenario.

This uncertainty explains why the government wisely chose to maintain its programme in Phase 2 and then evaluate the results. With this information at hand, it can either affirm or modify the course, that is, make that decision once the necessary information reveals whether it is an issue of aligning expectations as the government believes (virtuous scenario), or if there is some fundamental adjustment needed, such as the exchange rate trajectory (scenario with tunings), as the market seems to believe.

In economic policy, policy makers cannot waver at the slightest difficulty. Persistence is not always synonymous with stubbornness or dogmatism but the optimal response when making decisions with imperfect information and uncertainty about the underlying reality in which economic policy operates and in a context where expectations can easily become unanchored.

Let us discuss these scenarios in detail, one by one.

4.1. The virtuous scenario: doubling down

In the virtuous scenario, the government achieves its objective: supported by the fiscal surplus and tight monetary policy, it ultimately convinces the market that there will be no step devaluation of the official dollar. The sale of dollars to meet liquidity needs in pesos accelerates, the gap is reduced to a level low enough to unify the foreign exchange market and lift the exchange rate controls smoothly.

The removal of exchange rate controls stimulates inflows of capital that are presumed to be waiting for their removal to invest in key sectors of the economy, partly under the recently approved Large Investments Incentive Regime (known as RIGI in Spanish). This fosters an economic recovery (and remonetisation), leading to an accumulation of international reserves that reduces the risk of refinancing dollar debt coming due and country risk.[1]

4.2. The complex scenario: an unsustainable programme cannot be sustained

In the complex scenario, the government does not achieve its objective in a more or less immediate time frame but insists on maintaining the exchange rate policy. In this scenario, the market does not believe that the current exchange rate trajectory is consistent with the accumulation of reserves and despite the restrictive supply of pesos, there are no dollar sales (implying a decline in the real demand for money). The gap between the parallel and the official dollar does not close to levels compatible with unifying the foreign exchange market and lifting exchange rate controls. The inflow of capital does not materialise, international reserves continue to fall, refinancing risk dollar debt coming due increases and so does country risk. The economy does not recover or remonetise.

It is a usual phenomenon in Stabilisation Plans, that the price to pay for earning market credibility is a deeper and more prolonged recession than would be necessary if there were perfect credibility in government policy announcements.

However, in this specific case, a more prolonged and deeper recession is not neutral: over time, without a sound economic recovery, the political capital that the government still holds and the social tolerance displayed by the population despite the severe fiscal adjustment and drop in incomes may weaken, questioning the cornerstone of the entire scheme: the fiscal balance. If political and social pressures make it unviable to maintain fiscal balance, the scheme collapses from its foundations.

4.3. The scenario with tunings: if the mountain won’t come to Muhammad…

If the strategy does not yield the desired results in a more or less short period of, the government may opt to change course by devaluing the official exchange rate to unify it with the parallel rate, lifting exchange rate controls and ensuring an exchange rate trajectory consistent with the accumulation of reserves. This implies that the BCRA will need to buy dollars in the market at the unified exchange rate while maintaining fiscal balance and tight monetary policy.

This strategy is not without risks, as it may result in a temporary setback in the fight against inflation and both inflation and exchange rate expectations could easily become unanchored.

One way to mitigate these risks is by securing a new agreement with the IMF to help to shield the programme and manage expectations. It would be inconceivable that, in such a scenario, the IMF would not offer a new programme to Argentina.

Conclusions

Can the zero-deficit-zero monetary expansion-2% devaluation programme achieve its objectives? Certainly, it can.

But if Phase 2 of the plan does not work as expected and the market is not convinced that the current official exchange rate trajectory is sustainable, the exchange rate gap between the parallel and official dollar does not close to the extent or speed needed, international reserves dwindle, country risk does not decrease, the government may opt to adjust the exchange rate path flexibly by devaluing the official dollar to unify it with the parallel rate (from the official to the parallel), consider lifting capital controls and ensure a trajectory of the unified exchange rate consistent with an increase in international reserves, to reduce country risk, trigger capital inflows and facilitate economic recovery.

Effectively implementing this adjustment and doing so in time to avoid the weakening political capital and social tolerance for fiscal adjustment that could potentially compromise the fiscal balance, will require the ability to rapidly adapt to circumstances and a surgical precision to make necessary changes without destabilising inflation and exchange rate expectations. One way to mitigate these risks is to secure a new agreement with the IMF to help to shield the programme and manage expectations (it would be inconceivable that, in such a scenario, the IMF would not offer a new programme to Argentina). All of this is within reach of an economic team that, under extremely complex circumstances, has so far operated with skill, pragmatism and decisiveness.

This framework of uncertainty explains why the government wisely chose to double down on its programme in Phase 2 and evaluate the outcome. With this information at hand, the government can either ratify or rectify its course, that is, make that decision once the necessary information reveals whether the issue about aligning market expectations with the economic programme as the government believes (virtuous scenario), or if there is some fundamental adjustment needed, such as the exchange rate trajectory (scenario with tunings), as the market seems to believe.

In economic policy, policy makers cannot waver at the slightest difficulty. Persistence is not always synonymous with stubbornness or dogmatism but the optimal response when making decisions with imperfect information and uncertainty about the underlying facts in which economic policy operates and in a context where expectations can easily become unanchored.

[1] The authors would like to thank Pablo Ottonello, who reviewed the first version of this analysis and with whom they had stimulating discussions that contributed to enrich it. They would also like to thank Guillermo Calvo, Sara Calvo and Alejandro Izquierdo for valuable comments. Opinions and errors are the authors’ responsibility alone.

[2] For a detailed description of the policies implemented in Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the Stabilisation Plan, see The BCRA Introduced a Monetary Framework Aimed at Consolidating Price Stability. Gerencia de Comunicación Estratégica, BCRA.

[3] The Incentive Regime for Large Investments (RIGI, in Spanish) is an initiative aimed at attracting significant domestic and foreign investments in key sectors of the Argentine economy: mining, oil and gas, renewable energy, agribusiness and technology. It offers a range of fiscal, customs and exchange rate benefits to promote large-scale projects.