In partnership with http://www.iai.it/

Theme

The authors assess the first year of the EU-Turkey statement on refugees, providing a summary of the current situation.

Summary

In 2015 the EU faced one of the most severe crises in its entire history. The refugee flows from the Aegean Sea caused a humanitarian drama that required a rapid response. While one particular member state, Greece, has been the most affected, another transit country, Turkey, has played a crucial role. A candidate country and also a long-term economic partner, Turkey was there to keep refugees out, as the guardian of Europe’s borders. Externalising the issue seemed the best option to European leaders after the many inconclusive attempts of the European Commission to relocate asylum seekers among the EU’s member states. With an unexpected revitalisation of relations with the aim of delegating irregular migration flows, Turkey and the EU concluded a deal to halt these flows to Europe. The EU-Turkey Statement was signed on 18 March with the proviso of certain concessions to be made Turkey, such as opening up chapters in its accession negotiations, €3 (plus €3) billion and, most importantly, visa-free travel for its citizens. Nevertheless, the deal was immediately subject to criticism from many sectors. One year on, an honest assessment is very much needed since the EU is considering the designing of new deals with other transit countries. In the meantime, both Turkey and key countries of the EU, such as the Netherlands, France and Germany, are facing very critical electoral challenges of their own. For this reason, internal politics and foreign policy decisions are highly interwoven.

Analysis

Introduction

While the world witnessed one of the most tragic refugee crises of its history in 2015, the EU got itself into an impasse due to its member states’ clashing interests and their inability (or unwillingness) to find a common solution to this global challenge.1 Despite the European Commission’s efforts and the publication of the European Agenda on Migration,2 this profound solidarity crisis led to the blunt refusal by some member states to implement the relocation system as approved by the EU Council in September 2015.3 As no common solution was found to distribute migrants and asylum seekers fairly among the member states, the decision was taken to strengthen the EU’s cooperation with countries of both origin and transit.4 With a Syrian refugee population at the time of around 2 million,5 and being the main transit country for migrants to the EU through the Balkan route, Turkey was identified as the provider of the solution to the European deadlock.6 On 29 November 2015, the EU’s heads of state or government held a first meeting with Turkey to develop EU-Turkey relations and draw the lines of a new cooperation agreement to manage the migration crisis.7

On 18 March 2016, during a second International Summit, EU leaders and their Turkish counterparts signed the EU-Turkey Statement, better known today as the EU-Turkey deal.8 According to the statement, all migrants crossing the Aegean Sea illegally would be readmitted to Turkey, while for every Syrian returned to Turkey from Greek islands, another Syrian would be resettled from Turkey to the EU, in a process that became known as the “one-to-one mechanism”. In exchange, the EU promised to re-energise Turkey’s accession process by opening up chapters, speeding up visa liberalisation and investing a €3 billion financial packet plus an additional €3 billion to improve the standard of living of the Syrian immigrant community in Turkey.9 While welcomed in Brussels as a positive step to addressing the ‘migration crisis’, the deal sparked heated criticism among international human rights organisations and civil society for being in breach of international laws such as the ban on collective expulsions. In particular, many opposed the decision to consider Turkey a ‘safe third country’ –ie, a country that is safe for third-country nationals–.

One year after the EU-Turkey statement, externalisation (or the effort to externalise migration control) is the cornerstone of the European strategy to address the migration challenge. On 3 February 2017 Europe’s leaders met in Malta to devise an action plan with Libya to halt irregular migration through the Central Mediterranean route.10 While the EU-Turkey statement might become a model for future deals with other countries, it is important to evaluate its effect at one year’s remove from its implementation. On the one hand it seems to have achieved its main goal, with the number of migrants crossing from Turkey drastically dropping in the weeks following March 2016. However, the situation is not as bright as it might seem, to the point that many observers are envisaging that the deal might break down. The growing political instability in Turkey, combined with a worsening of its relations with the EU, is also playing against the partnership designed to cooperate on migration management. This paper assesses the first year of the accord’s implementation, looks at its main effects and will try to answer the one question that remains in the air: will the deal break down in the near future?

Stemming the flow across the Aegean Sea: data evidence

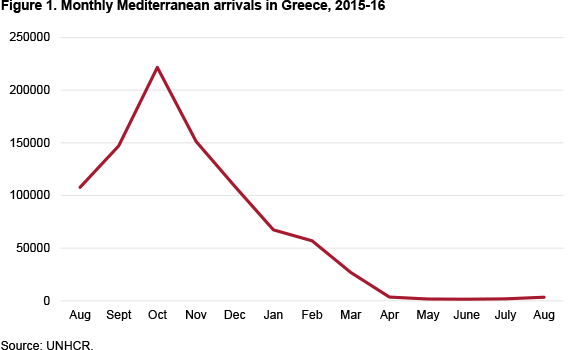

One of the declared aim of the EU-Turkey Statement –better known as the EU-Turkey deal– is to ‘end irregular migration from Turkey to the EU’.11 Data evidence suggests that the flow of irregular migrants crossing the Aegean Sea did in fact slow down. However, a critical approach to the numbers reveals that the causal relation between the EU-Turkey deal and the drop in irregular crossings is not as clear as it might seem.12 After the peak in October 2015, the number of irregular crossings to Greece did in fact slow down, mostly due to the poor weather conditions of the winter months. In addition, the progressive closure of the Balkan route since September 2015, as the result of the closure of the border between Hungary and Serbia and the subsequent construction of a barbed-wire fence along the Hungarian-Serbian and Hungarian-Croatian frontiers,13 had already deterred migrants from undertaking the perilous journey through the Aegean Sea.14 In short, the combined effect of the Balkan route closure and the EU-Turkey statement resulted in migration across the Aegean Sea remaining very low even in the summer months of 2016.

Nevertheless, the EU has frequently resorted to the rhetoric of preventing migrants from dying at sea to justify the agreement with Turkey. On this point there is no doubt that it has failed to achieve its goal: 2016 has been the most tragic year, with over 5,000 people dead while attempting to reach Europe by crossing the Mediterranean.15 The sharp increase from the 3,771 recorded in 2015 may well be the result of migrants tending to use the Central Mediterranean, the deadliest route. In short, even if the deaths on the Aegean have decreased, as underlined various times by the European Commission, this is not, however, unfortunately the case when taking into account the Central Mediterranean route as well.

Political and legal challenges to the deal

International organisations criticised the EU-Turkey deal from day one,16 claiming that Turkey cannot be considered a ‘safe third country’. The concept of ‘safe third country’ is the legal basis for the deal, as it allows the EU to return migrants and asylum seekers to Turkey without violating the non-refoulement principle.17 Reports and studies have shown that Turkey is indeed not a ‘safe third country’ for either asylum seekers or refugees.18 Additionally, the country’s domestic situation has deteriorated dramatically over the past year, following the attempted coup of July 2016. As a result, legal challenges to the return of asylum seekers from Greece to Turkey are on the increase. Furthermore, asylum requests filed in Greece must be assessed on an individual basis before a potential return to Turkey, as this would otherwise amount to mass expulsions. As a result, in April 2016 Greece adopted a new law (Law 4375/2016) to fast-track asylum procedures at the border.19 The law envisages a two-step process: before considering an application on its merits, the individual concerned must pass an admissibility assessment. Until recently, only Syrians have been subject to the admissibility procedure to decide whether they should be returned to Turkey. According to the EU-Turkey statement, most Syrians should be returned to Turkey: however, the Greek Appeal Committee has overturned the vast majority of the appeals, arguing that Turkey does not qualify as a ‘safe third country’, thus blocking a central element of the deal itself.20 According to the latest figures provided by the European Commission, arrivals continue to outpace the number of returns from the Greek islands to Turkey, as the total number of migrants returned since the date of the EU-Turkey Statement is only 1,487.21

The new procedure puts a disproportionate bureaucratic burden on Greece’s asylum system by establishing a de facto double formula for those in the islands –who need to undergo an admissibility and then an eligibility process– and those on the mainland –who undergo only the eligibility process–.22 Besides, the fate of those sent back to Turkey is also worrying: the UN Refugee Agency, entrusted by the deal to monitor the situation of returnees in Turkey, has expressed on several occasions its concern over the situation of Syrians readmitted to the country.23 It also reported obstacles to the regular access to refugee camps in Turkey and to monitor whether anyone sent there from Greece is given legal protection.24In addition, the reception conditions on the Greek islands, inadequate already before the deal, has worsened dramatically: the camps there have been transformed into detention facilities for those waiting a response on their eligibility –ie, on whether they can seek asylum in Greece or should be returned to Turkey–. By the end of 2016 around 15,000 people were still stranded on the islands in dire conditions.25

The legal nature of the EU-Turkey Statement is itself unclear, as the EU’s negotiators failed to follow EU procedure for concluding treaties with third countries.26 For this reason it is called a ‘statement’ and not an agreement, since it has not been approved by the European Parliament. As a result, the EU General Court has declared that it has no jurisdiction over a case presented by three asylum seekers against the agreement,27 placing a clear distinction between the member states and the EU itself.

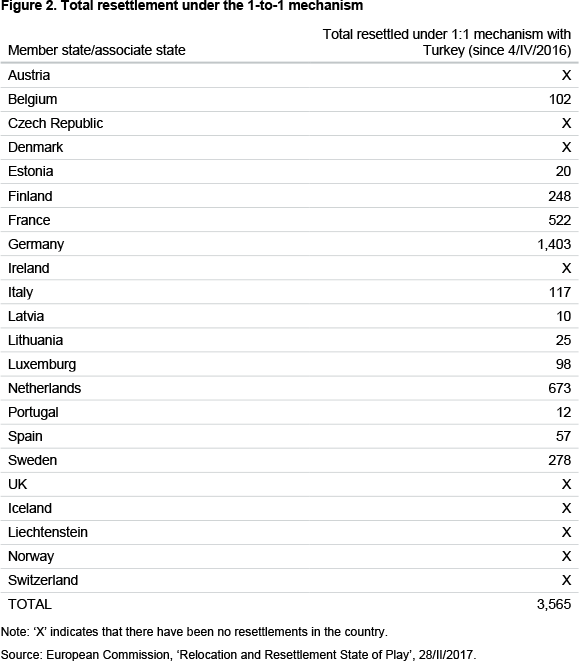

The part of the deal that was best received –safe passage to Europe, also known as the ‘1-to-1 mechanism’– it also not working properly. Only 3,565 Syrian refugees have been resettled from Turkey to Europe, a negligible number compared with the goal of resettling 72,000, and even more so compared with the almost 3 million Syrians in Turkey.28 Figure 2 shows the number of individuals resettled from Turkey according to the agreement. Germany has by far accepted the highest number. The reason lies not only in the size of its population and its economic situation but also in the fact that it is the key country behind the design and negotiation of the deal with Turkey. The Netherlands and France followed Germany’s lead: being founder members of the EU they are merely assuming their responsibility.

Will unfulfilled promises be the breaking point?

Another aspect of the settlement is that relations between the EU and Turkey have unexpectedly revived. Since the EU was unable to find a fair solution for the allocation of asylum seekers among its member states, the only way of ‘solving’ the problem was its externalisation. Thus, there was a revitalisation of its relations with Turkey, since it is the main transit country for Syrian refugees. However, the situation was merely circumstantial as there is no convergence of interests when it comes to migration management.29 The agreement has also been criticised widely since Turkey’s democratic credentials are quite problematic as regards basic rights and freedoms, and this was even aggravated following the attempted coup. Bearing all this in mind, it is important to underline the following promises made to Turkey:

- Lifting the visa requirements for Turkish citizens. Turkey has been given 72 benchmarks for achieving visa-free travel to the Schengen Area, among which it has fulfilled 67. One of the remaining benchmarks, revision of the anti-terror law, faced constant resistance from the Turkish side, leading to a deadlock. The issue of visa-free travel for Turkish citizens to the Schengen area is considered the deal’s ‘core’ part by the European Commission as it has already been on the agenda for a long time.

- Opening negotiation chapters in Turkey’s accession process. However, only one chapter has been opened following the signing of the deal.30

- ‘3-plus-3 billion euros’. According to the European Commission, of the €2.2 billion already allocated for 2016-17, contracts have now been signed for 39 projects to the value of €1.5 billion, all of which have begun to be implemented.31

- Resettlement from Turkey, also known as the 1-to-1 rule. As noted above, 3,565 refugees have been resettled.

‘Visa liberalisation is a core part of the EU-Turkey Statement of 18 March which is designed to decrease irregular migration. The proposal for placing Turkey on the visa free list also clearly specifies that the visa exemption is dependent both upon continued implementation of the requirements of the visa liberalisation roadmap and of the European Union-Turkey Statement of 18 March 2016.’ 32

Within all this process, the institutional division between the Commission, the Council and the Parliament has been highly visible. The Commission and the Council have appealed to realpolitik and tried to maintain the deal despite worsening conditions in Turkey following the attempted coup. On the other hand, there is also the European Parliament’s non-binding decision on freezing negotiations, with the aim of imposing some kind of sanction. However, the decision was not further promoted by a Council decision, and all of the deals financial stipulations have remained in place.

Conclusions

The deal: can it –and should it– be maintained?

An assessment one-year on of the deal’s implementation should also take into consideration that it came at a time when Brussels was gridlocked vìs-a-vìs the migration crisis. Therefore, there was no time for detailed debates in the EU to find a more adequate and long-term solution to the challenge. The Statement could have provided space for further discussion but instead it proved to be the first step in the reinvigoration of the EU’s externalisation policy. Even more, a critical approach to the EU-Turkey deal is now necessary since the EU is considering striking similar deals with countries such as Libya, Egypt and Tunisia.33 But there are still two main questions to consider:

- Can the deal hold?

- Should the deal hold?

The answer to the question of whether it can, depends on:

- A further deterioration of conditions in Syria that might lead to a rising inflow of Syrians.

- Greece’s capacity to handle the situation further, regardless of its lack of administrative and financial capacities.

- Domestic issues in Turkey and the further deterioration of the country’s safety conditions.

- The possibility of serious social unrest between Turks and Syrians. So far it appears that the Turkish government has no problem with having so many Syrians within its borders. There are even draft proposals to provide them with Turkish citizenship. Meanwhile, neither has Turkish public opinion been overly negative about the situation so far, although the granting of citizenship is not viewed positively. Furthermore, the government has relocated Syrians to Kurdish areas in south-eastern Turkey, which could be construed as social engineering designed to stem the rising Kurdish nationalism. In this regard, social unrest might well be a possibility.

- The Turkish government’s reaction to unfulfilled promises. The country’s President has threatened the EU on several occasions with sending migrants on into Europe if the economic part of the deal is not complied with. The most important unfulfilled part of the deal is visa liberalisation for Turkish citizens. In general, the intention of linking the refugee deal and Turkey’s accession process to the EU ended up being more of a problem than a positive conditionality. The underlying logic was the rejuvenation of relations, or at least the maintenance of a working link. However, it led to a further deterioration in mutual trust and a greater estrangement between the peoples of Turkey and the EU.

- And lastly, it depends mostly on the current state of the relations between the EU and Turkey. At present, the relationship has worsened significantly, both as a whole and as regards specific tensions with certain member states, notably Germany and the Netherlands. There are currently discussions on a possible complete breakdown in the event of the ‘yes’ vote triumphing in the Turkish constitutional referendum, which has dramatically been criticised by the Venice Commission ‘as a dangerous step backwards for democracy’.34 Should this be the case, there is likely to be a thorough reconsideration of the future of Turkey-EU relations.

All these points are vital for the deal to remain on track and they largely depend on domestic conditions in Turkey and Greece, the two key countries involved in the deal, in addition to on the relations between Turkey and the EU. Even if the deal survives for a while more, outsourcing the problem can never be a permanent or long-term solution.

As to the second question, whether the deal should hold, the answer comprises elements of realpolitik, humanitarian concern and the legal rights of refugees. The EU-Turkey statement has set a dangerous precedent by demeaning ‘the principle of the right to seek refuge itself’. It may well erode the EU’s image as a defender human rights, considering the closure of the Western Balkan route, the poor treatment of asylum seekers at the borders of European countries and the dire standards of living on the Greek islands.35 For this reason, continuing the policy of externalisation may require the creation of a firmer legal framework.

As a concluding remark, the decline in the number of illegal crossings in the Aegean, which is considered the deal’s main positive result, needs to be critically assessed. It should have provided the EU with sufficient scope to further discuss a long-term solution to the migration crisis. It should be borne in mind that the EU-Turkey statement involves only Syrian refugees but not those of other nationalities. This is a further reason why the EU-Turkey statement should merely be considered a stop-gap measure that must be replaced with a more stable and longer-term strategy. However, facing one of the most critical electoral years in the EU’s history, it is unrealistic to expect a fair assessment of the current situation.

İlke Toygür

Analyst, Elcano Royal Institute | @ilketoygur

Bianca Benvenuti

Istituto Affari Internazionali | @BeyazBi

1 İlke Toygür & Bianca Benvenuti (2016), ‘The European Response to the Refugee Crisis: Angela Merkel on the Move’, IPC-Mercator Policy Brief, June.

2 European Commission (2015), ‘A European Agenda on Migration’, COM (2015), Brussels, 13/V/2015.

3 Council Decision (EU) 2015/1601, 22/IX/2015.

4 Informal Meeting of Heads of States and Government, 12/XI/2015.

5 According to UNHCR data, there are currently 2,910,281 refugees in Turkey. See UNHCR, Syria Regional Refugee Response for the most recent figures.

6 Meltem Müftüler-Baç (2015), ‘The Revitalization of EU-Turkey Relations: Old Wine in New Bottles?’, IPC-Mercator Policy Brief, December.

7 Meeting of Heads of State or Government with Turkey – EU-Turkey Statement, 29/XI/2015.

8 International Summit, Press Release 144/16, 18/III/2016.

9 The EU leaders had already agreed to a €3 billion fund in the aforementioned November 2015 meeting. See Meeting of Heads of State or Government with Turkey – EU-Turkey statement, 29/XI/2015.

10 European Council, Press Statement 43/17, 3/II/2017.

11 Press Release 144/16, EU-Turkey Statement, 18/III/2016.

12 Thomas Spijkerboer (2016), ‘Fact Check: Did the EU-Turkey Deal Bring Down the Number of Migrants and of Border Deaths?’, Border Criminology, 28/IX/2016.

13 Friederich Ebert Stiftung, ‘At the Gate of Europe: A Report on Refugees on the Western Balkan Route’.

14 EurActive (2016), ‘Balkan Route closed after cascade of border shutdowns’, 9/III/2016.

15 UNHCR, ‘Operational Portal: Mediterranean Situation’.

16 Amnesty International (2016), ‘EU-Turkey Refugee Deal a Historic Blow to Rights’, 18/III/2016; Human Rights Watch (2016), ‘Say No to a Bad Deal With Turkey’, 17/III/2016; and Médecins Sans Frontières (2016), ‘Migration: Why the EU’s Deal With Turkey is No Solution to the “Crisis” Affecting Europe’, 18/III/2016.

17 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugee (1951), Art. 33.

18 See, among others, Ahmet İçduygu & Evin Millet (2016), ‘Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Insecure Lives in an Environment of Pseudo-Integration’, IAI Working Paper 13, August; Amnesty International (2016), ‘EU Reckless Refugees Returns to Turkey Illegal’, 2/VI/2016; UNHCR (2016), ‘Legal considerations on the return of asylum-seekers and refugees from Greece to Turkey as part of the EU-Turkey Cooperation in Tackling the Migration Crisis under the safe third country and first country of asylum concept’, 23/III/2016; StateWatch Analysis (2016), ‘Why Turkey is Not a “Safe Country”’, February; Human Rights Watch (2016), ‘Is Turkey Safe for Refugees’, 22/III/2016; and Orçun Ulusoy (2016), ‘Turkey as a Safe Third Country’, Border Criminology blog, University of Oxford, 26/III/2016.

19 Aida (2016), ‘Greece: Asylum Reform in the Wake of the EU-Turkey Deal’, 4/IV/2016.

20 In June 2016 the Greek Parliament changed the composition of the Appeal Committees. By the end of 2016, the new Committee upheld 20 inadmissibility decisions of the Greek Asylum Service. See Amnesty International (2017), ‘A Blueprint for Despair: Human Rights Impact of the EU-Turkey Deal’, January.

21 European Commission (2017), ‘Report From the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council: Fifth Report on the Progress made in the Implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement’, 2/III/2017.

22 ‘More than Six Months Stranded – What Now? A Joint Policy brief on the Situation for Displaced Persons in Greece’, October 2016.

23 UNHCR (2016), ‘UNHCR concern over the return of 10 Syrian asylum-seekers from Greece’, 21/X/2016.

24 UNHCR (2016), ‘Response to query related to UNHCR’s observation of Syrians readmitted in Turkey’, 23/XII/2016.

25 Amnesty International (2017), ‘A Blueprint for Despair: Human Rights Impact of the EU-Turkey Deal’, January.

26 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Part Five – Title IV, Article 218. For more on this see ‘EU Law Analysis. Is the EU-Turkey refugee and migration deal a treaty?’, 16/IV/2017.

27 General Court of the European Union, Press Release 19/17, Luxemburg, 28/II/2017.

28 European Commission (2017), ‘Report From the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council: Fifth Report on the Progress made in the Implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement’, 2/III/2017.

29 For further information see Bianca Benvenuti.

30 Official negotiations for Chapter 17 were opened in December 2015. In addition, official talks for the negotiation of Chapter 33 were opened in June 2016, putting the item on the official timeline for EU-Turkey relations.

31 For further information see ‘Report From the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council: Fifth Report on the Progress made in the Implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement’.

32 For more information see ‘Questions & Answers: Third Report on Progress by Turkey in fulfilling the requirements of its Visa Liberalisation Roadmap’, Brussels, 4/V/2016.

33 Peter Seeberg (2016), ‘The EU-Turkey March 2016 Agreement As a Model: New Refugee Regimes and Practices in the Arab Mediterranean and the Case of Libya’, IAI Working Paper, December.

34 For more information see the Venice Commission’s opinion.

35 For more information see the Human Rights Watch report.