Theme: The so-called ‘Fiftieth Anniversary Report’, which was published at the end of January 2006, makes a thorough assessment of Morocco’s fifty years of independence, on both the social and economic levels.[1]

Summary: Along with the Report of the Equity and Reconciliation Commission (Instance Equité et Reconciliation, IER) on human rights’ violations committed up to 1999, the Report on ‘50 years of Human Development and Prospects for 2025’ –entrusted by the King of Morocco to a numerous group of independent experts under the direction of one of his advisors– is part of the same retrospective review and collective reflection effort on the political experience of Morocco since it achieved independence in 1956. The Report studies, from the perspective of human development, the socio-economic advances that have been made by the country over this half century, but also analyses its unresolved shortcomings and the prospects for 2025. The challenge now is to convert this enlightened diagnosis into a programme of political action ‘in order to reach a high level of human development’. Nevertheless, to date it is not very clear how this task is to be achieved.

Analysis: The Report itself is made up of 186 pages, and it has attached a complete ‘Graphic Atlas’ with over 200 graphs. However, as is natural in this type of exercise, the report has a certain air of political correctness about it; indeed, it even becomes patriotic at times, focusing on results and not on evaluating the policies that explain them. Nevertheless, it does not avoid facing up to questions such as ‘the key issue as to whether or not, over these 50 years, it might have been possible to do things better: the answer from the perspective of an observer in our day would most likely be a straightforward “yes”’. Neither does it brush over the Gordian knots that characterise the scenario to be expected over the next couple of decades on which the future of Morocco will depend: ‘a shortfall in terms of governance, a shortfall in terms of knowledge, unequal access to healthcare, insufficient job creation, limited social mobility, maintenance of the scale of poverty and vulnerability in absolute terms, a deficit in terms of local development, a deteriorated environment’.

Moreover, in an unprecedented exercise of transparency, all of the thematic preparatory reports have been published, which make up a total of 4,500 pages written by about a hundred authors in the form of 75 thematic contributions and 16 cross-section reports, which offer a detailed, uncompromising insight into the deep social transformations experienced over the last fifty years and the policies applied during that time. All of these can be consulted in their entirety on the Internet.[2] These are contributions from acknowledged experts on all possible aspects of socio-economic realities, grouped together into broad themes. Though the work was co-ordinated by Abdelaziz Meziane Belfqih, the most intellectual of the Royal advisors, with the help of a Management Committee entrusted with the General Report and a Scientific Committee made up of the thematic scientific co-ordinators, the tone and critical content of the contributions are surprising for their freedom of spirit and the forthrightness of the analyses therein expounded. Furthermore, the authors have stated that they were not subject to any substantial interference in the course of their work. It has been a thorough exercise that has been duly legitimated by the credibility of the members of the team of authors –the cream of Moroccan academics and socio-economic consultants and of the country’s intellectual elite, including the current Moroccan ambassador to Spain, Omar Azziman– and which allows an exhaustive and in no way indulgent assessment of the first fifty years of the country’s independence, without avoiding issues such as the social and political role of religion –the report identifies three trends: the Islamisation of all spheres of society, secularisation and the assignment of the central role of the Moroccan state to the institution of the Commander of the Faithful (p. 24)– and constitutional reform, albeit within the framework of the ‘perennial nature of the basic options’, to the extent in which at ‘the end of a long, hard road of 50 years, it has been possible to find a great consensus with respect to the institutions and the basic options facing the country’.

Whatever the case, it is a genuine guideline and frame of reference for anyone who wishes to learn about present-day Morocco from any one of a number of perspectives, ranging from the most anecdotal of data (it is estimated that only around 30% of Moroccan homes have washing machines and only 50% have a refrigerator, while 76% have a television set), by way of a study of the ‘50 years of literary production in Morocco’ according to which it is estimated that between 1985 and 2003 12,400 books were published in the country (only 52 of which are in Amazigh-Berber language), to the most sophisticated analysis of social stratification and mobility, or a ‘Report on the conceptual, legislative and regulatory framework of the decentralisation and regionalisation process in Morocco’. All of the foregoing is arranged under ten broad headings: demography and population; society, family, women and youth; economic growth and human development; the educational system, knowledge, technology and innovation; the health system and the standard of living; access to basic services and spatial considerations; poverty and social exclusion factors; the natural heritage, the environment and territories; cultural, artistic and spiritual dimensions; and governance and participatory development. Moreover, three cross-themes are included: a synthesis of the historical evolution of Morocco as an independent nation; a study of the prospects for Morocco up to 2025; a comparative study of Morocco and a sample of 14 countries over the 1955-2004 period (the sample includes the following countries: Spain, Portugal, Greece, Ireland, Chile, Mexico, Egypt, Tunisia, Jordan, Turkey, Poland, Malaysia, South Korea and South Africa); and a study of Moroccan values.

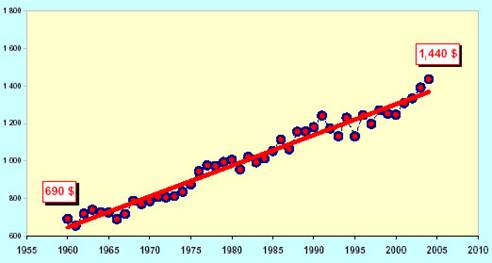

Over these 50 years, as is stated in the Report, the balance is neither ‘all white, nor irredeemably black’. Much progress has been made: GDP per inhabitant has nearly doubled since 1960, and has been growing at an accumulated average annual rate of 1.7% (See Graph 1). Nonetheless, in comparative terms, Morocco’s achievements have been relatively moderate in comparison to other central Maghreb countries, such as Tunisia (which became independent in the same year), or Algeria (which achieved its independence in 1962, though in this case the existence of hydrocarbons explains almost everything).

Graph 1. Annual Evolution of GDP per Inhabitant in US Dollars Since 1960

Source: ‘Fiftieth Anniversary Report’, General Report, p. 101.

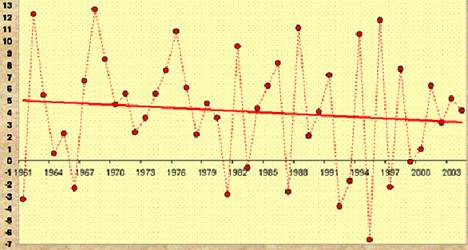

Nevertheless, the annual growth rate is on a downward trend –though this is a feature that is common to practically all of the sample countries used for comparison purposes– and shows a high degree of volatility, in line with rainfall levels, which continue to determine the economic situation (see Graph 2). Furthermore, estimates suggest that Morocco’s growth potential is limited, due to its limited internal market and low total factor productivity (ie, the contribution of technology and innovation to growth not explained by the use of labour and capital factors). In terms of growth, the comparative study with the other sample countries show that Morocco has suffered a negative spread in the 1960s and 1990s, the latter being put down to ‘the frequency of the droughts, the difficult situation of our European partners, a not very well adapted specialisation profile of Morocco and a lack of economic policy reactivity’, though as far as the latter is concerned no further analysis is forthcoming. As far as the relationship between governance and economic growth is concerned, the comparative study reflects the findings of a French study that attributed an annual loss of 1% of Morocco’s growth rate to corruption and an 0.9% annual loss to the lack of competition in its markets, with a total annual loss of growth of 2.5% being attributable to institutional factors. As far as the quality of the democratic state is concerned, Morocco is in the second-last position of the fourteen countries studied, only ahead of Mexico.

Graph 2. Annual Growth Rate of the Moroccan Economy

Source: ‘Fiftieth Anniversary Report’, Graphic Atlas (www.rdh50.ma/fr/pdf/RDH50.pdf), p. 185.

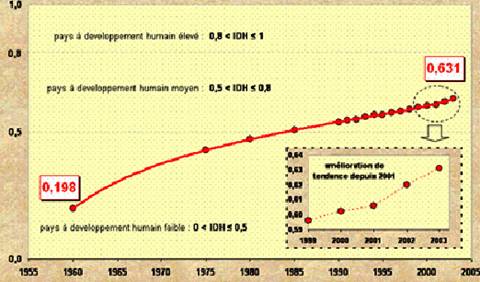

In addition, the UNDP Human Development Index has experienced an overall improvement that has enabled Morocco to extricate itself from the group of low human-development countries after 1985, and life expectancy has passed from 47 to 71 years of age, that is to say, an increase in life expectancy of 25 years over a mere 50-year period (see Graph 3, which also shows an apparently positive change in trend as of 2001), as well as a significant increase in schooling rates and an improvement in health and infrastructure indicators (80% electrification has already been achieved, and should be completed by 2007). However, the Report reveals with a wealth of detail that Morocco continues to show social indicators that are well below its income level; indeed, the employment rate for women who have reached the working age continues to be under 20%, while over 40% of the population still have no access to the drinking water network, not to mention the problems of access to housing and the existence of shanty towns.[3] It is quite revealing that the factorial analysis carried out in the comparative study with another 14 countries [4] clearly indicates that the main explanatory variable for Morocco’s lagging behind is its low educational indicator (despite spending 6.5% of its GDP on education, which is more, for example, than Spain and all the other comparison sample countries, except for Malaysia) and low use of new technologies, which affords a couple of clues as to what the expenditure and short-term co-operation priorities need to be. On the other hand, Morocco’s total public and private health expenditure (4.6% of its GDP) is the lowest of the fifteen countries studied, with the exception of Malaysia, and has remained stagnant since 1995, which explains its mediocre health indicators.

Graph 3. Evolution of Morocco’s Human Development Index (UNDP)

Source: ‘Fiftieth Anniversary Report’, Graphic Atlas, www.rdh50.ma/fr/pdf/RDH50.pdf.

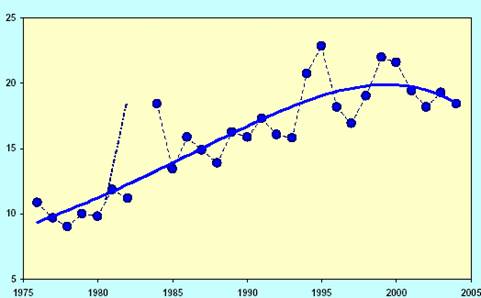

Over the last thirty years, the urban unemployment rate has grown by no less than five percentage points per decade: it was over 10% of the working population in 1982, reached a level of 15% in the 1990s and verged on the 20% mark in 2000, although there was a slight drop thereafter (see Graph 4). The number of jobless has risen, according to official figures, from 304,000 in 1960 to 1,300,000 at present, while Moroccan emigration figures have also risen from 1.1 million in the mid-1980s to the current figure of 2.6 million nationals that now live abroad. In this respect, the demographic transition phase that Morocco is undergoing opens ‘a window of demographic opportunity that may become a genuine demographic gift if enough jobs are created’. Nevertheless, the Report does not insist on this ‘missing link’ in the chain of future prosperity, nor does it stop to look into its consequences, or into the lack of a national employment policy as the big issue pending resolution in Morocco’s economic transition.

Graph 4. Evolution of the Urban Unemployment Rate (% of the Working Population)

Source: ‘Fiftieth Anniversary Report’, Graphic Atlas, p. 106.

Political Significance

However, beyond its specific content, which represents a veritable socio-economic encyclopaedia of contemporary Morocco, it is reasonable to ask about the political meaning of this exercise. Inevitably, the Fiftieth Anniversary Report has its origin in a royal speech given on 20 August 2003 in which Mohamed VI called for the ‘the celebration of independence to serve as a moment of reflection to assess the stages on the road travelled by our country as regards human development in this half century, highlighting the successes, the difficulties and the ambitions, and to learn the lessons from the choices made during this historical period’. In the letter commissioning the task to his royal adviser he demanded ‘fairness and objectivity’ in the analysis to be made. The work began in December 2003 with the setting-up of the Managing Committee and the Scientific Committee, subsequent to which there was a first grand meeting held in April of 2004, and culminated in the presentation of the Report at the end of January 2006. Though the Synthesis Document and the General Report have been criticised for not being the result of a consensus and for not reflecting the great diversity of expert standpoints that have taken part in the entire process, the truth is that the experts’ contributions have been published in their entirety, and that the experts have acknowledged the fact that they enjoyed a high degree of independence in the course of their work.

That an exercise of this scope does not end in a set of coherent proposals aimed at avoiding the repetition of the mistakes of the past, as expressly indicated, for example, in the Report of the Equity and Reconciliation Commission (IER) mandate, is another matter altogether. Paradoxically, the fact that the management of the whole process was commissioned to a royal adviser leads us to wonder as to the political ends of the exercise. In this respect, the Report could be said to constitute the acceptance of a political heritage after inventory by the new King, rather than a framework for political action in the future.

In any case, the ‘apolitical’ nature of the Report has been underlined by the fact that resort was had solely and exclusively to university experts for its writing, without giving rise to any type of consultation with civil society, or with the political parties, although one of the contributions commissioned is about ‘Values: changes and perspectives’ and consists on an objective sociological study, based on a national survey of values undertaken by a consultancy firm, in which society and social groups are treated as the object of study and not as a political subject. Unlike the IER Report, the Fiftieth Anniversary Report included neither public hearings, information and discussion sessions in schools, television debates at prime time viewing hours nor individual files on violations of economic and social rights arising from the lack of human development.

On the other hand, the academic and scientific focus that has been given to the process does not seem to fit in with the fact that the entire report on prospects for 2005 was entrusted exclusively to a Palace civil servant, Mohammed Tawfik Mouline. In fact, the 60 ‘strategic leads’ and ‘improvement axes’ in the political, economic and social spheres that are offered as conclusions and an ‘invitation to debate a 2025 Agenda’ are, for the most part, nothing more than well-intentioned guidelines devoid of concrete content, such as: ‘delving into and maturing collective reflection on constitutional reform issues in the light of the lessons learned from the experience’, ‘multiplying spaces for the expression and discussion of ideas’, ‘extending the scope of the micro-credit’, ‘urging the formalising of the informal sector by means of tax simplifications and the organising of its trades’, ‘initiating a reflection on our exchange rate regime’, ‘meeting all of the conditions required to secure the success of the reforms that are under way’ (education, culture and training), ‘providing a clear and transparent solution to the linguistic divide in our country’, and so on up to all 60 topics. Whatever the case, it is certainly not comparable with the unequivocal mandate of the Equity and Reconciliation Commission to formulate a set of recommendations and proposals to ensure that violations of human rights ‘are not repeated’. And, indeed, it has nothing to suggest a revision of the reform paradigm that is under way, beyond that of the diagnosis given in the ‘Report on the prospects of Morocco up to 2025’ to the effect that Morocco finds itself in ‘a human development situation that continues to be unviable’ (p. 31). Any solutions that are offered all point to incremental reforms within the framework of the current model. Though it would appear that during the preparatory meetings questions such as ‘the monarchy as an obstacle to development in Morocco’, or the claim that ‘in the light of the reports presented, we are heading directly for the abyss’, were discussed, obviously these types of approach were consigned to oblivion in the final Report and in the contributions. In fact, this continuist focus is reflected in the only two scenarios covered in the analysis of the prospects for the next 20 years: ‘two contrasting visions of our country looking ahead to 2025, depending on our capacity to achieve, or not, as the case may be, the consolidation of the transitions that have already been started and to successfully complete the new reforms that we need’. As if there were no other paths towards human development.

It is also striking, given the apparent duplication, that at the same time, and invoking the same royal speech, the Plan Commission (Haut Commissariat au Plan), responsible for strategic planning in Morocco, devoted itself over the course of 2005 to a collective reflection exercise about the Morocco of 2030 on the basis of two forums on ‘Morocco and its Geo-strategic and Economic Environment in 2030’ and ‘Moroccan Society: Continuities, Changes and Future Scenarios’, followed by 17 thematic studies which are currently under way and a series of surveys on the vision that journalists, students and writers have of 2030.[5] The results of this exercise, which should materialise in the production of a series of scenarios for conditions 25 years ahead, have still not been published.

Whatever the case, although the Fiftieth Anniversary Report Synthesis Document states that its main aim is clearly ‘to encourage a large-scale public debate on the policies that must be applied in the near and more distant future’, both the Report and the forward-looking exercise come at a time when the Moroccan Government seems to have adopted all of the basic social, political and economic options for the next years and undertaken all of the large-scale modernisation projects: the reform of the Family Code (the Mudawwana) which entered into force in February 2004, the National Initiative for Human Development (INDH) launched in May 2005,[6] the major Free Trade Agreements with the European Union and the United States (which came into force in March 2000 and January 2006, respectively), the industrial development Emergence Programme, the new Labour Code enacted in December 2003, the Political Party Law of 2005, etc. Unless, of course, the Fiftieth Anniversary Report be understood as an exercise in the a posteriori justification of these reforms.

On the other hand, unlike the report by the Equity and Reconciliation Commission on violations of human rights up to 1999, the recommendations of which have been conveyed to the Human Rights Council for application, as far as the Fiftieth Anniversary Report is concerned there has been no political follow-up beyond that of their publication. Indeed, it has not been formally presented to the Parliament, or to the Government, and no commission has been created within the Administration to come to the relevant conclusions and to make the most of the lessons to be learned from these fifty years of independence. In this respect, it could be said that it is almost an exercise in political dilettantism.

Conclusion: Of What Political Use?

Whatever the case, the Fiftieth Anniversary Report has served to establish the adoption of human development as the official vision and philosophy of development in Morocco (as the ‘conceptual backbone’ of all policies, as stated in the Report itself), and health, education or housing as genuine political priorities, as reflected by the National Initiative for Human Development (INDH). Moreover, the Report provides a thorough and relatively objective analysis of Morocco’s socio-economic evolution over these five decades in all its aspects, which is in itself something of great value: the wealth and diversity of the contents of its 4,500 pages make it difficult to summarise in a note as short as this. On the other hand, its political use and usefulness are not as clear, given that it does not finish up with a series of concrete political recommendations and proposals, nor has any specific procedure to translate its contents into political actions for the future been established (as stated in the Synthesis Document, ‘the Report has deliberately avoided adopting a forward-looking, or programmatical, discourse, given that it understands that it is the political actors who should draw up such programmes, as well as legitimately debate them’). Nonetheless, from this standpoint it is difficult to understand why the whole Fiftieth Anniversary Report has been assigned the following slogan: ‘The future is to be built and the best is possible’. Indeed, the major economic and social policy options in Morocco seem to have been adopted prior to the Report, and to this extent –and given that social and political forces did not collaborate in its writing– the Report could end up being simply an academic diagnostic exercise, albeit very sophisticated and critical, but lacking any direct political impact. That is to say, although there is no doubt that the Report will indeed contribute to fuelling the public debate as it proposed to do, one cannot see it contributing to a greater participation of the public in the definition of the major political courses for Morocco in the forthcoming decades.

Iván Martín

Universidad Carlos III, Madrid

[1] The present ARI is part of the work of the Maghreb Monitoring and Analysis Group (GASEM), under the direction of Haizam Amirah Fernández.

[2] See http://www.rdh50.ma/. The 47-page Summary Document has even been translated into Spanish: www.rdh50.ma/esp/docsynthese_esp.pdf.

[3] See Vulnerabilidades socioeconómicas en el Magreb (I): Los riesgos del chabolismo en Marruecos, ARI nr 36/2005, Elcano Royal Institute, available at ARI 36/2005

[4] Available at www.rdh50.ma/fr/pdf/rapports_transversaux/benchmarking%20.pdf.

[5] See www.hcp.ma for information on this initiative.

[6] SeeMorocco: The Bases for a New Development Model? (I): The National Initiative for Human Development (INDH), ARI nr 35/2006, Elcano Royal Institute, available at ARI 35/2006.