In partnership with https://www.ifri.org/

Theme

Europe’s southern neighbourhood is a diverse but interlinked geopolitical ensemble, whose specificities need to be carefully assessed before Europeans devise dedicated security strategies, divide responsibilities and make policy decisions.

Summary

This exercise in geopolitical scoping seeks to make sense of the main security challenges present in Europe’s broader European neighbourhood, a space encompassing areas as diverse as the Gulf of Guinea, the Sahel, North Africa, the Levant and the Persian Gulf. It identifies (some of) the main sub-regions that make up the ‘South’, offers an overview of the threat environment in each of them and identifies relevant differences as well as common themes. In doing so we aim to provide a conceptual referent for further policy research on the security of Europe’s ‘South’, and to help inform future strategic and policy discussions within the EU, NATO and their Member States.

Analysis

Both the 2016 EU Global Strategy and NATO’s 2016 Warsaw Summit declaration identify Europe’s southern neighbourhood as an area of strategic priority. However, neither organisation has so far provided a clear-cut definition of the geopolitical parameters of the so-called ‘South’, offered a clear picture of the kind of security challenges present therein or explained how they matter to Europe from a geopolitical perspective. It is important to clarify these aspects before entering any sort of discussion about strategy or designing any lasting policy response to the challenges emerging from the South.

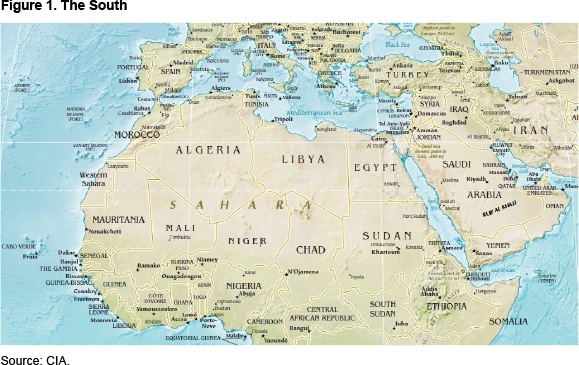

In its narrowest form, the label ‘South’ is used to refer to those countries of the Mediterranean rim that do not belong to either the EU or NATO. For instance, the EU’s Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) and European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) include or aspire to include all the countries situated in North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco, Libya and Tunisia) and the Levant (ie, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria).1 NATO’s Mediterranean Dialogue follows a somewhat similar principle, in that it includes all North African countries from Mauritania to Egypt (excluding Libya, for political reasons) and two countries from the Levant: Jordan and Israel.

A broader definition of the South would expand the scope to encompass the space running from the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, through the Sahel, North Africa and the Mediterranean all the way to the Levant and Mesopotamia and then, through the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa, all the way to the Persian Gulf. This broader area or extended southern neighbourhood has gained increasing popularity in EU and NATO circles in recent years, with many experts alluding to the growing importance of the ‘neighbours of the neighbours’.2

Recent EU and NATO efforts to broaden the (geographical) scope of the South are understandable. European countries realise that the security and stability of their immediate southern neighbourhood (ie, the southern and eastern Mediterranean basin) is inextricably tied to developments in adjacent geographical areas. For the EU, this ‘broadening’ has led to the adoption of regional strategies for the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and the Gulf of Guinea/West Africa, which underscore the links between those areas and Europe’s immediate southern neighbourhood (ie, the Mediterranean proper). In addition to strategies, the EU has deployed missions and operations in the Mediterranean, Sahel and Horn of Africa areas, conducted within the framework of the Common Security and Defence Policy.

NATO, for its part, has in recent years been dragged into discussions about how it can contribute to the security of Iraq (deeper in Mesopotamia), whilst the presence of Turkey pushes for a more expansive geographical definition of the South, to include the broader Middle East. Thus, the Alliance’s Euro-Mediterranean dialogue and Istanbul Cooperation Initiative are increasingly referred to as different instruments to deal with an expanded South. Moreover, the Warsaw Summit has included the Sahel-Sahara region as an area of interest for the Alliance.3 However, in contrast to the EU, no explicit references have been made in NATO documents to the Gulf of Guinea and/or West Africa.

Taking into account the above considerations, it could be argued that the so-called South (in its extended version) could be broken down into seven main geopolitical referents or sub-theatres, namely: West Africa and the Gulf of Guinea, the Sahel, North Africa, the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Red Sea-Arabian Sea corridor and the Persian Gulf (ie, Iran and the countries of the southern Persian Gulf), and the (rest of the) Arabian Peninsula. Admittedly, this categorisation is just as arbitrary as any: these seven areas or sub-theatres can be regrouped differently as well as broken down into equally meaningful sub-categories (for example, it could be argued that the security dynamics in north-east and north-west Africa are very different, or that Egypt in many ways belongs in the Levant category). In this sense, it may be worth pointing out Libya’s specific importance as a geopolitical meeting point of sorts within the South, ie, one that acts as a transmission belt of a variety of threats and challenges irradiating from the Sahel and North Africa as well as the Levant. Be that as it may, it is a categorisation that promises to offer Europeans a useful starting point to help them organise and conceptualise the different challenges emanating from the South.

If the geographical parameters of the South are inherently contested, so is the nature of the security threats and challenges emanating from it. Over the last few years, much emphasis has been placed on irregular migration and human trafficking (a problem that bears both human rights and security concerns), as well as terrorism itself, whose possible connection with uncontrolled migration flows is as unclear as it is polemical. These two issues have been underscored by NATO and the EU, both of which have emphasised the importance of the so-called internal-external security nexus. But they are amongst the many security challenges emanating from the South. Other salient challenges relate to piracy and insecurity at sea, which can disrupt sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and threaten Europe’s energy security and trade, and drug trafficking. Ultimately, many of these challenges can be traced back to the endemic weakness or failure of several states in the South, a structural problem that acts as generator and magnifier of various kinds.

The prominence of state failure, terrorism, piracy, organised crime or uncontrolled migration flows means there is a tendency to associate the South with low-level and transnational security challenges. Such challenges are central, no doubt. However, when it comes to the South, Europeans cannot remain aloof from military-strategic developments at the higher end of the threat spectrum. The proliferation of precision-strike munitions and weapons in parts of the South is perhaps particularly noteworthy.4 While the proliferation of precision-strike systems in Europe’s South may still be relatively immature in terms of its technological sophistication, several state and non-state actors are exploiting the advantages offered by precision-guided munitions to progressively build up their own capabilities in creative ways. Iran and Syria perhaps stand out.5 But even terrorist and rebel groups are making forays into precision strike. Hizbollah already used anti-tank guided missiles against Israel in the 2006 Lebanon war, whilst Hamas has often used guided-missiles against civilian targets in Israel. Likewise, more recently, Houti rebels in Yemen have fired anti-ship missiles at US naval vessels in the Red Sea. The prospect of hostile state or non-state actors in possession of precision-strike capabilities at or near the South’s key maritime chokepoints (ie, the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Bal el Mandeb, the Suez Canal and the Strait of Gibraltar) is particularly relevant for Europeans, and demands greater strategic attention.

Once the geopolitical and security parameters of the South have been more or less identified, a key question arises: which South-related threats (or challenges) matter most, where and how? While we acknowledge that there is no satisfactory way to address that question, below we try to offer the foundations of a conceptual model that can help make better sense of the South’s inherent complexity, by correlating geography and the threat environment. In this regard, we identify three main geopolitical areas:

- An inner or core ring in the immediate southern European neighbourhood, which share the Mediterranean with Europeans (formed by North Africa and the Levant). It goes without saying that these countries are of direct interest to Europeans. First, because of their geographical proximity, any changes in their economic, political and social situation, or in their strategic capabilities, is likely to be directly and deeply felt in Europe. They are of direct economic interest for Europeans, and their markets may offer future opportunities. They are perhaps particularly interesting from an energy security perspective, whether as an important source of European gas imports (eg, Algeria and Libya), by virtue of their role as transit countries for gas coming from beyond the immediate neighbourhood (eg, Turkey and Morocco) or of their potential in areas like solar energy. They are also of interest because of people-to-people and cultural ties, in that many European citizens originate from these countries. This translates into a greater sensitivity in Europe about their political evolution, not least due to the existence of relevant pressure groups and epistemic communities with a greater interest in those countries.By virtue of their proximity, this inner ring also matters greatly from a strictly military-strategic perspective. The proliferation of precision-guided munitions in the Levant and North Africa threatens to complicate European power projection in those areas –and could even pose a defence challenge for Europeans in the future–. Syria is a case in point. Russian-made, precision-guided surface-to-air missiles and thousands of anti-aircraft guns make up an advanced Syrian air-defence network that makes it increasingly difficult for Europeans to project power there. Relatedly, the changing military balance in the Levant and Eastern Mediterranean raises questions about Europe’s ability to preserve its political influence in those key areas.6 Yet, when it comes to Europe’s immediate southern neighbourhood, the problem posed by precision-strike proliferation could soon transcend Syria and the Levant. Egypt, Algeria and even terrorist groups in countries like Libya, are also likely to take advantage of precision-guided weapons in coming years, potentially posing a direct military threat to Europe in some cases.Secondly, because of their geographical location (straddling Europe and the ‘deep South’), these core southern countries play a key role in terms of regulating the impact that any political, economic or security dynamics at play in the ‘deep South’ may have upon Europe. Thus, North African countries play a key role in preventing or mitigating trafficking in persons, weapons or drugs coming from the Sahel or West Africa. Likewise, the Levant both filters and shields any instability that might come from Mesopotamia or the Persian Gulf area, whereas Egypt (straddling the Levant and North Africa and overlooking the Suez Canal) does the same for the Red Sea area. In this regard, stability in these core areas is a key geopolitical priority for Europe to the extent that it can help shield Europe from instability emanating further afield or, at least, mitigate it. Hence the importance of developing strong and lasting political, economic, societal and security ties with these inner-ring countries, with a view to building up their resilience and ability to shield Europeans from challenges emanating from further afield.

- Two intermediate areas (the Sahel and Mesopotamia) situated further afield give strategic depth to the core regions of North Africa and the Levant and, arguably, also to the two outer areas (see below). The Sahel provides strategic depth to North Africa, West Africa and the Gulf of Guinea area: some of the challenges and threats that are ‘cooking’ in the Sahel often ‘boil over’ in other parts of the southern neighbourhood –and go on to ‘let off steam’ in Europe itself–. Mesopotamia straddles the Levant and the Persian Gulf, and has a pervasive impact upon these two areas. A good example is the current situation in Iraq and Syria, which is simultaneously explained by meddling from countries situated in the Levant and the Persian Gulf, as well as having a negative impact in those regions by way of migration, refugees, disruptions in economic supplies and insecurity.For its part, the Persian Gulf not only has an impact on Mesopotamia and, through it, the Levant proper, but also on the Arabian Peninsula, the Arabian Sea and Red Sea continuum. As already argued, both of these areas matter primarily to the extent that they have a pervasive impact upon political, social and security dynamics in Europe. In particular, the lack of state control over large swathes of these intermediate areas, whether in the Sahel (eg, Mali) or the Levant (eg, Iraq and Syria), constitutes a breeding ground for terrorism (local and transnational), arms proliferation, organised crime and uncontrolled migration flows. Europeans should therefore help strengthen the security services of some of the countries in these intermediate spaces, reinforce their border-control capabilities and build up their political resilience.

- Two outer areas that delimit the maritime perimeter and regulate the entry and exit into Europe’s southern neighbourhood: the Gulf of Guinea in the south-west and the Red Sea-to-Arabian Sea corridor in the south-east, which includes the Gulf of Aden and Persian Gulf. These areas present a number of challenges and opportunities for Europeans. An important challenge relates to piracy, especially in the Gulf of Guinea and the Gulf of Aden areas –this can disrupt vital European SLOCs–. The importance of the Persian Gulf as an energy source for Europe is well known. The Gulf of Aden is critical in that it filters the passage of energy from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean (and Europe), as well as the vital trade line connecting Europe with South and East Asia. The Gulf of Guinea is also an important source of energy for Europeans, as well as an area of transit for energy imports from south-west Africa (especially Angola), and strategic minerals and metals from southern Africa. Another challenge, that is perhaps specific to the Gulf of Guinea relates to drug trafficking, with the Gulf acting as a transit area for illicit goods flowing from the Americas to Europe, through the Sahel and North Africa or through the West-African coast.Given the importance of the gulfs of Guinea and Aden to the security of Europe’s SLOCs, and their exposure to piracy, Europe needs to strengthen its investment in Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) and local capacity building, not least with a view to reinforcing the indigenous security capabilities of those areas in which there is a direct link between state weakness/failure and piracy (such as Somalia and Yemen). Last but not least, Europeans need to strengthen their defences against precision-strike attacks against shipping in these chokepoints, whether those currently emanating from terrorist groups operating from failed states (such as Yemen and Somalia) or, more seriously, the potential of state actors to more significantly threaten the security of European SLOCs (eg, Iran in the Persian Gulf). Iran’s so-called Anti-Access and Area Denial (A2/AD) strategy combines technologically sophisticated elements –such as advanced air defences, cruise missiles and even attack submarines– with the application of precision-guided systems to more ‘rudimentary’ munitions, such as rockets or mortars. These capabilities mean that Iran may already be in a position to either block or substantially threaten passage through the Strait of Hormuz, thus menacing a vital European SLOC as well as threatening European allies and interests in the Persian Gulf. This problem is perhaps further compounded by Iran’s advances in missile technology (and its potential to reach Europe), and the lingering shadow of its nuclear programme. Given these trends, Europeans should perhaps strengthen their contribution to theatre air and missile defence in the southern Persian Gulf, as well as to their own defence against ballistic missiles, with a view to the future.

Conclusions

Europe’s South is neither unidimensional nor monothematic. It is an inherently diverse but interlinked geopolitical ensemble, whose specificities need to be carefully assessed before devising dedicated security strategies, distributing responsibilities and making policy decisions. The ‘South’ can be a land of opportunities for Europeans, given its economic, demographic and energy potential. But such opportunities can only be realised if its geopolitical dynamics are properly understood and existing security threats and challenges are effectively addressed. This geopolitical scoping exercise makes clear that an appropriate policy mix requires the involvement of a number of actors. Solutions to the various security challenges emanating from the South are likely to come from the active engagement of individual European countries, especially those who have a more direct stake in fencing off possible threats (eg, France, Spain, Italy, for instance), clusters of European and neighbouring countries (such as the 5+5 Dialogue) as well as multilateral organisations like the EU and NATO. This adds yet another layer of complexity to approaching the South, not least as the perspectives and threat assessments of this myriad of countries, clusters and organisations may at times diverge.

Luis Simón

Director of the Brussels office of the Elcano Royal Institute, and research professor at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel | @LuisSimn

Vivien Pertusot

Head of the Brussels office of the French Institute of International Relations (Ifri) | @VPertusot

1 Although, in a strictly geographical sense of the word, Jordan does not border the Mediterranean and is therefore not part of the Levant, it is commonly treated as part of it.

2 See, eg, Sven Biscop (2014), ‘Game of Zones: The Quest for Influence in Europe’s Neighbourhood’, Egmont Paper nr 67.

3 Warsaw Summit Communiqué, NATO.

4 See, eg, Luis Simón (2016), ‘The “Third” US Offset Strategy and Europe’s “Anti-Access” Challenge’, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 39, nr 3, p. 417-445.

5 See, eg, Mark Gunzinger & Christopher Dougherty (2011), Outside-In: Operating from Range to Defeat Iran’s Anti-Access and Area-Denial Threats, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, Washington DC; and Sina Ulgen & Can Kasapoglu (2016), ‘A Threat Based Strategy for NATO’s Southern Flank’, Carnegie Europe, 10/VI/2016.

6 See Sinan Ülgen & Can Kasapoğlu (2016), ‘A Threat Based Strategy for NATO’s Southern Flank’, Carnegie Europe, 10/VI/2016.