Theme[1]: The promotion of ‘good governance’ has become one of the pillars of development policies proposed by a large majority of development aid agencies. It is based on the view that ‘good governance’ is a pre-requisite for development. The author critically reviews the relationship between governance, growth and development and draws implications that are relevant for Sub-Saharan African countries.

Summary: There is today a broad agreement that governance is critical for development but much of the consensus about how governance matters is still very deficient. The liberal revolution in development economics and policy thinking that took place in the 1980s had a critical effect on the debate about the role of the state and therefore about the governance capabilities that developing countries should aim to achieve. The emerging good governance agenda defends the need in developing countries to have policies that stabilise property rights and engage in rule-of-law reforms, carry out anti-corruption and anti-rent seeking strategies, engage in democratisation and accountability reforms, and sustain these through the mobilisation of the poor through the prioritisation of pro-poor spending by governments. This paper provides a critical assessment of the theoretical and empirical basis of these approaches to governance and development. It suggests that some of these reforms may be desirable but are not implementable to a significant extent in any developing country. Instead, other governance capabilities, namely the capabilities of states to intervene effectively and address market failures, are more effective to achieve improvements in resource mobilisation and the efficiency of investment allocation.

Analysis

Introduction

The recognition that governance is important for economic development is a very welcome one. Governance is what states do, and the recognition that governance is important is therefore an important recognition that the capabilities of states are important determinants of economic and social performance in developing countries during the process of development. There is today a broad agreement that governance is critical for development but much of the consensus about how governance matters is still very deficient. Not surprisingly, serious debates have emerged about the types of governance that are important, and the sequencing of governance reforms in developing countries.

The Context of Governance Debates

The governance debate needs to be understood in the context of broader debates within development economics and development policy. Up to the 1970s the consensus in development policy was that states needed to intervene to correct market failures. The post-colonial experience of developing countries was based on the poor experience of many significant developing countries like India, with free-trade policies during the colonial period which had resulted in poor economic performance. Developing countries under colonial free-trade had become poorer relative to the imperial countries. The post-war consensus in the 1950s and 1960s was that developing countries needed to address the market failures that had resulted in their stalled progress with industrialisation and growth. Unfortunately, the results with state intervention in this period were problematic in most developing countries. While a handful of countries in East Asia did extremely well with state-driven policies, most did not. While most countries with infant industry policies performed better than they had under colonialism, many faced growing problems with budget deficits, balance of payments deficits or other fiscal problems by the 1970s. This was often the result of poor capabilities of their states to discipline the subsidies that they were allocating to accelerate industrialisation or agricultural development.

The liberal revolution in development economics and policy thinking that took place in the 1980s had a critical effect on the debate about the role of the state and therefore about the governance capabilities that developing countries should aim to achieve. Instead of responding to the experience of the 1960s and 1970s by focusing on how to develop effective state capabilities to address market failures more effectively, the new consensus argued that market failures were due to the state interventions themselves. Market failures should therefore be reduced by reducing government intervention and by reducing transaction costs in markets through the stabilisation of property rights, achieving a rule of law and other reforms that have collectively come to be known as ‘good governance’ reforms.

The Good Governance Framework

The new consensus thus came to identify a series of capabilities that were necessary governance capabilities for a market-friendly state. In this way, stable property rights, a good rule of law, a commitment to anti-corruption policies and a high level of government accountability stopped being just some of the goals of development to become vital preconditions for development. The new liberal consensus on market-driven growth drew on a particular reading of New Institutional Economics to derive these conclusions. These theoretical propositions argue that:

- Efficient markets are the most important requirement for prosperity. This is a fundamental proposition that emerged with the new liberal economics of the 1980s. It is an important proposition because it under-plays the importance of market failures in developing countries and argues that development can be achieved by developing markets. While there is no dispute that markets are vital institutions for ensuring efficient private contracting, there is a considerable dispute about whether developing market institutions are sufficient for solving the many investment and production problems faced by developing countries.

- The second proposition is that efficient markets require low transaction costs. Transaction costs are simply a measure of the costs of contracting in markets. By definition, market failures are ultimately due to high transaction costs. In effect, the new consensus was saying that market failures could be effectively addressed by making markets so efficient that market failures would disappear. Implicitly, there was a significant change here from the previous development consensus. In the earlier consensus, the transaction costs causing market failures in developing countries were considered to be so significant that immediate and significant reductions in these transaction costs were thought to be unfeasible. Therefore, many significant market failures would remain and had to be addressed through intervention. It was this proposition that the new consensus directly challenged.

- The final proposition was that good governance reforms would lower transaction costs. The governance reforms that have become known as good governance reforms were therefore necessary for the emergence of an efficient market economy. These reforms would work by reducing market transaction costs and thereby allowing more rapid development.

The theoretical linkages in the new consensus are shown in Figure 1. Economic stagnation was explained by high transaction cost markets (link 1). The latter were, in turn, due to contested or weak property rights which resulted in difficulties in contracting. Market inefficiency was further raised by welfare-reducing government interventions that increased uncertainty in markets and often raised the costs of efficient entry and exit (link 2). These inefficient property rights and interventions in turn survived because small groups of people benefited from these conditions and were engaged in corruption and rent seeking to sustain the conditions from which they performed (link 3). But since corruption and rent seeking benefited only small groups by definition, the persistence of corruption and rent seeking was in turn explained by the absence of government accountability, which allowed small groups to benefit at the expense of the majority (link 4). Finally, the economic stagnation that was created by these conditions in turn created the conditions for perpetuating them because poverty allowed small groups of the wealthiest people to monopolise power (link 5). Thus, once poor governance and market failures had become locked in, they became very difficult to dislodge.

Figure 1 . Theoretical Linkages in the New Consensus

The new policy agenda that is now widely recognised as the good governance agenda is directly derived from this new theoretical consensus. The new agenda says that it is no longer enough to simply focus on liberalisation and other market-promoting strategies. It is simultaneously important to have policies that stabilise property rights and engage in rule-of-law reforms, carry out anti-corruption and anti-rent seeking strategies, engage in democratisation and accountability reforms, and sustain these through the mobilisation of the poor through the prioritisation of pro-poor spending by governments. These links are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 . The New Policy Agenda

A Critical Assessment

There is no question that many of the reforms identified by the good governance consensus are desirable in themselves. Who could be against lower corruption or more effective democracy or a good rule of law? The question is really about whether these desirable capabilities are actually the most important necessary governance conditions for ensuring development in poor countries. Prioritisation is important given the limited reform capabilities and resources available for implementing reform in poor countries.

A second and even more important related question is whether the governance goals of the ‘good governance agenda’ are achievable in poor countries. We could in theory identify many reforms that might help to enhance market efficiency, but if these reforms cannot be significantly implemented in poor countries because of various structural constraints, then these reforms are not the best ones upon which to focus.

Therefore, we need to ask whether the good governance reforms are necessary for growth and development and to what extent they are achievable.

If we find that the reforms while desirable are not implementable to a significant extent in any developing country, then we should be looking for other governance capabilities that are feasible and which could help sustain growth and development in poor countries. If the good governance reform agenda diverts our attention away from achievable reforms that are based on the experience of successful developing countries then it could be doing significant damage to developing countries. This would be the case if the history of development showed that market failures could not be removed by making markets more efficient in the way the good governance agenda assumes, and that the feasible governance strategy is to try to achieve the state capabilities that make intervention to correct market failures somewhat more effective.

Case-study evidence strongly suggests that successful developing countries did not achieve good governance before they began to develop as a precondition for development. Rather, they developed because they had state capabilities that allowed them to overcome significant market failures, and they began to approximate to good governance conditions rather late in their development trajectories. This evidence can be visually presented using some of the data provided by the World Bank, though the data is regularly interpreted in a very different way by consensus economists who support the good governance propositions.

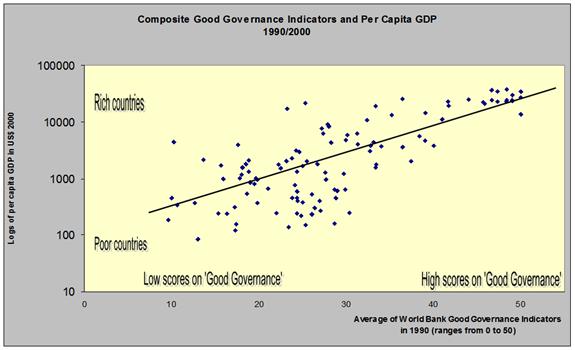

Figure 3 . Good Governance Scores and Per Capita Incomes

Figure 3 shows why at first sight the good governance propositions appear to make a lot of sense. The indices of good governance that are used in these charts come from the World Bank and are based on subjective indicators of good governance provided by opinion surveys. As such, they are problematic indicators of underlying governance characteristics, but for the crude demonstration that is required for now they will suffice. If we look at the relationship between scores on ‘good governance’ and per capita incomes, there is clearly a very strong relationship. However, the relationship does not establish causality because rich countries could have high good governance scores because they are rich, rather than being rich because they have high scores in good governance.

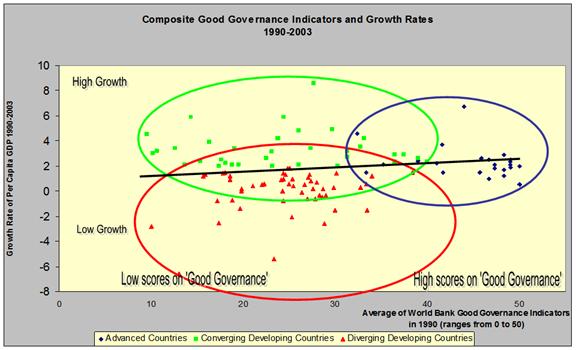

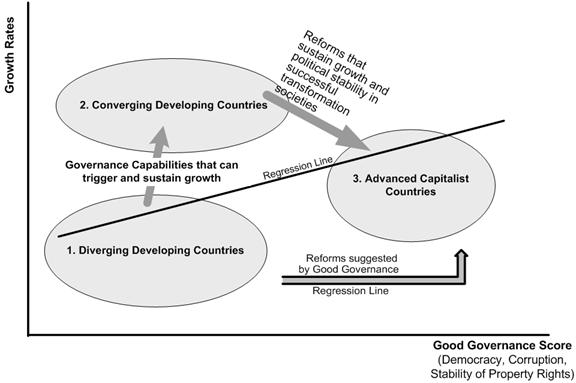

However, if we look at the relationship between good governance and growth rates we get a much more complex picture, as shown in Figure 4. Here we divide developing countries into two groups: a diverging group that has growth rates lower than the median advanced-country growth rate and a converging group that is growing at a faster rate than the median advanced country. Advanced countries clearly have better good-governance scores than developing countries and are shown separately. The interesting comparison is between the converging and diverging developing countries. In Figure 4 it is visually clear that converging and diverging developing countries do not have any significant difference in their mean good-governance scores or in the dispersion of their good-governance scores. This rough observation is entirely in line with all the case-study evidence that supports the same conclusion, namely that high-growth developing countries did not first achieve high scores in good governance.

Figure 4 . Good Governance and Growth Rates

The historical evidence suggests that converging countries did not differ from diverging countries in their good-governance capabilities, but clearly did differ in their ability to sustain growth. If we leave out accidental growth stories driven by fortunate endowments of raw materials or other historical accidents, sustained growth requires capabilities to overcome market failures, which we know are likely to be significant given poor scores in good governance and therefore high market transaction costs in all developing countries. A stylised representation of governance priorities for developing countries is shown in Figure 5. For poorly-performing developing countries in group 1, the good-governance advice appears to be to move from group 1 to group 3 by first moving rightwards by improving the state’s good-governance capabilities. The historical evidence, in contrast, is that there is no example of a country that did this. The real challenge for group 1 countries is to learn about the critical governance capabilities that countries similar to them in group 2 had which allowed them to grow much faster. And for many group 2 countries, the challenge is to understand better the often accidental capabilities that allowed them to grow so they can build on these to sustain their growth. An unfortunate fact of history is that many countries that were briefly in group 2 often fall back into group 1. The challenge of developing good-governance capabilities is also a real one, but typically we find the transition to significant improvements in good governance to happen rather late in development, at mid to upper middle income levels. This does not mean that some improvements in good governance cannot or do not happen at very low levels of per capita incomes, but these improvements are still going to keep these countries at significantly low levels of good governance for a long time.

Figure 5 . A Stylised View of Governance Priorities

This historical evidence is not at all surprising. If we look at some of the conditions that are required to achieve significant improvements in good-governance conditions, it becomes quite obvious why these improvements are not observed in developing countries. For property rights to become ‘stable’, society and ultimately the owners of assets have to pay for their effective protection. This requires that most assets in society are productive to the extent that their owners are able to pay significant taxes. The protection of property is a public good but is not a free good.

Similarly, fighting corruption also requires fiscal resources. It is often argued that poorly-paid bureaucrats are a source of corruption. But, in fact, a much more significant source of corruption in poor countries is political corruption. Politicians, whether democratic or otherwise, need to generate resources to keep their constituents happy in a context where public redistribution through the budget is not likely to provide sufficient resources to satisfy powerful client constituencies. Social democratic politics only becomes sustainable when fiscal resources are sufficient not only for paying bureaucrats properly, but also for funding critical public goods and achieving transfers that can attract winning electoral coalitions behind fiscal promises. Finally, it is important to remember that not all good-governance theory is correct. There is a significant amount of useful rent seeking in all societies, because rent seeking can drive useful institutional change. In advanced market economies there is a significant amount of rent seeking but it is mostly legal and regulated. This includes processes like lobbying, the work of think tanks and contributions to political parties. All of these regulated processes are also expensive and only likely to become significant in rich societies.

The cost of politics also explains why reasonably accountable electoral politics only emerge when parties can offer enough to broad constituencies through the budget to win elections. In poor countries this is unlikely to be the case. That is why even in long-lasting developing country democracies like India, democracy involves significant political corruption and the accountability of leaders to the vast majority of the electorate is low.

Conclusion: All these observations do not mean that good governance is not desirable, but they do mean that significant improvements in good governance might not be immediately achievable. Indeed, there is no evidence that any poor country has achieved significant improvements in good governance, and plenty of evidence that high-growth developing countries achieved growth using the same levels of good-governance capabilities as the low-growth countries. At the same time, small but important improvements in good governance are both possible and desirable and may have an important impact on the life of critical constituencies. The important observation is rather that feasible improvements in good governance are unlikely to be significant enough to make an impact on growth and development.

If the feasible improvement in ‘good governance’ is small, then we have to look for other governance reforms to achieve improvements in resource mobilisation and the efficiency of investment allocation. The good governance agenda does damage precisely because it defines the agenda of governance in such a way that important governance capabilities are ignored. And, paradoxically, the most important governance capabilities may be the very capabilities that the liberal agenda tried to rule out, namely the capabilities of states to intervene effectively and address market failures.

Mushtaq H. Khan

Department of Economics, School of Oriental and African Studies, London

[1] This paper was the basis for a presentation by the author at a seminar on governance and development in Africa organised by the Elcano Royal Institute in Madrid on 15 September 2008. The author has published these ideas in different forms and in greater depth elsewhere. See, for example: Mushtaq H. Khan (2006), ‘Governance, Economic Growth and Development since the 1960s’, Background Paper for World Economic and Social Survey 2006, http://www.un.org/esa/policy/backgroundpapers/khan_background_paper.pdf; M.H. Khan (2006), ‘Corruption and Governance’, in K.S. Jomo & Ben Fine (Eds.), The New Development Economics, Zed Press, London, & Tulika, New Delhi, p. 200-221; Mushtaq H. Khan & Hazel Gray (2006), ‘Good Governance and Growth in Africa: What Can We Learn from Tanzania?’, in Vishnu Padayachee (Ed.), The Political Economy of Africa, Routledge, London, p. 339-56.