Theme: The Bolivian general elections were held in December 2009 in very special circumstances and conditions: they were the first elections under Bolivia’s New Political Constitution, the first (since the reinstatement of democracy) in which a President was eligible for reelection, the first in which biometric voter registration was implemented and the first in which it was possible to vote from outside the country.

Summary: The key issues in this campaign go beyond the simple difference in the number of votes obtained by the Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement towards Socialism, MAS), led by Evo Morales, and the number of votes going to his rivals. One of the opposition’s initial main goals was to prevent Morales from winning the presidency on the first ballot. For its part, a key goal for MAS in these elections was to obtain enough additional support in the east to give the party the majority not only in Congress, but also in the Senate. This goal was then extended to achieve a majority of two-thirds in both Chambers. Results gave Morales a solid majority which allows him to govern comfortably and modify the laws, including the Constitution. This ARI is aimed at providing a deeper understanding of these elections by studying the legal framework, the development of the new voter list, the inclusion of voters living abroad and the strategies of the opposition and the government.

Analysis: On 6 December 2009, general elections were held in Bolivia to elect the President, Vice-president, senators and members of Congress. These general elections were held early as a result of an agreement between the governing party, MAS, and opposition parties. It was agreed that if the New Constitution were ratified (as indeed was the case after the constitutional referendum held in January 2009), three steps would be taken:

- Early general elections would be held. This was a point of interest for the governing party. MAS strategists calculated that the implementation of expansive fiscal policies, together with holding the elections early, would increase the likelihood that they would take place in a favorable economic climate and that, as a result, MAS would continue in power.

- The incumbent President would be allowed to stand for re-election in these elections, given the new constitutional framework. From a practical perspective, this means that Morales is able to run again. This was a key point for MAS, since the party’s electoral victories were closely linked to Morales’ charismatic leadership.

- As a counterweight to the two points above, a new voter list would be developed to ensure that it was reliable and accurate. This was a key point for the opposition, who accused the government of major errors and inaccuracies in this regard.

New Biometric Voter Registration

The National Electoral Court (CNE) prepared biometric voter registration with significant security measures, such as digital photographs of voters and fingerprint scans, to ensure that voters were correctly identified.

The new biometric registration system has been a resounding success and the public has responded above expectations. CNE registered 5,139,554 voters, of whom 169,096 were Bolivian citizens living in Spain, Argentina, Brazil and the US. These figures set new historical records. The previous maximum number of registered voters was 4,544,171, for the hydrocarbons referendum in July 2004.

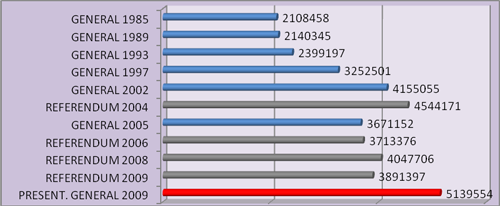

Figure 1. Growth of voter registration

There has been a very significant increase since previous elections. A total of 3,891,397 voters were registered for the January 2009 referendum and 3,671,152 were registered for the general elections in 2005. This substantial increase in the number of registered voters (32.1% and 40.0%, respectively) introduced an element of uncertainty and potential surprise in the results.

By region, the percentage increases over the 2009 referendum were: Tarija 45.7%, Beni 45.5%, Pando 38.3%, Santa Cruz 35.9%, Oruro 30.1%, Cochabamba 28.0%, Chuquisaca 24.6%, Potosí 20.2% and La Paz 15.3%. The first four regions had been characterised by strong opposition to the current government. However, this did not necessarily mean that the opposition had increased its voter base, since it was also possible that voters sympathetic to MAS constituted a significant part of the growth of the voter list in these regions.

The Vote Abroad

These elections were also the first in which Bolivian citizens residing abroad were able to vote. However, the vote abroad applied only to a limited number of citizens living in four countries: Spain, Argentina, Brazil and the US. The total number of voters registered abroad was somewhat less than expected, 169,096, due mainly to problems caused by the expiry of documents needed for registration.

The issue of the vote abroad had been the subject of controversy from the start. Since support for MAS is concentrated in the most underprivileged sectors of society, and since these sectors are theoretically overrepresented among emigrants, it is no wonder that MAS has pushed harder for this measure than anyone, while the opposition has been quite critical of it. The opposition had three main arguments against it: (1) they were worried by the difficulty of controlling the transparency of this voting system; (2) they suspected that there had been irregularities in the registration process abroad aimed at skewing the list in favour of the current government; and (3) the greater numerical importance, in terms of registered voters, of those countries where it was supposed that MAS would obtain favourable results.

The following table shows that the results of MAS abroad were ten points higher than at home. By countries, MAS won in Argentina and Brasil, PPB won in EEUU, and in Spain results were fairly balanced.

Figure 2. Distribution of the vote abroad

| Abroad | Argentina | Brasil | US | Spain | Abroad | Bolivia | TOTAL |

| MAS | 92.1 | 95.0 | 31.1 | 48.2 | 75.5 | 63.8 | 64.1 |

| PPB | 3.2 | 2.7 | 61.0 | 43.0 | 18.7 | 26.8 | 26.6 |

| UN | 1.4 | 1.3 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 3.1 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Registered | 89,953 | 18,142 | 11,006 | 49,995 | 169,096 | 4,970,458 | 5,139,554 |

Source: CNE and the author. 84%, 85%, 87%, 84% and 94.1% scrutinised, respectively.

Another reason the opposition distrusts the vote abroad is the potential relative weight it could attain. In developed countries –where this practice is more common– the vote abroad never accounts for more than 3% of the ballots cast, but in Bolivia it could become a determining factor, since an estimated 2 million Bolivians live abroad, compared with a population of about 8 million people living in the country.

Whatever might happen in the future, the vote abroad made up 3.4% of the list in these elections, and its impact in MAS’s victory was minimal –it raised its vote share from 63.8% to 64.1%–.

The Legal Framework

The President, Vice-president, members of Congress and senators were elected in December. These elections were the first call to the polls in the framework of the New Constitution and its implementing legislation, Law 1,984 (June 25, 1999) and Electoral Law 4,021 (April 14, 2009), which establishes the Transitory Electoral Regime.

First, the President and Vice-president were elected in a single national district. If a presidential candidate obtained 50% of the valid vote plus one, he was to be directly elected. A new feature of the regulatory framework –one that could eventually favour MAS’s interests– is that a candidate would have also been directly elected if he had received at least 40% of valid votes and were more than 10% points ahead of the second-place finisher. Otherwise, there would have been a second round of voting between the two candidates with the most votes in order for one to obtain a simple majority.

Second, the 130 members of Congress were elected in a mixed system that combined uninominal districts (first-past-the-post system), where election was by simple majority, and plurinominal districts (open party lists) with proportional representation by department (region). The system is made up of 70 uninominal and 53 plurinominal districts. A new feature of these elections is that seven special rural indigenous districts (Circunscripciones Especiales Indígena Originario Campesinas) had been created. These include more than one indigenous people and are also uninominal and function by simple majority.

Figure 3 . Deputies (Congress) by type and region

| Deputies | LP | SCZ | CBB | PTS | CHU | ORU | TJA | BEN | PAN | TOT |

| Uninominal | 15 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 70 |

| Plurinominal | 13 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 53 |

| Special | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Total | 29 | 25 | 19 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 130 |

LP: La Paz; SCZ: Santa Cruz; CBB: Cochabamba; PTS: Potosí; CHU: Chuquisaca; ORU: Oruro; TJA: Tarija; BEN: Beni; PAN: Pando.

Source: CNE and the author.

Finally, senators were elected by department in a plurinominal, proportional system with a minimum threshold of 3% of the vote. The new electoral framework increased the number of senators for each of the country`s nine departments from three to four.

The Battle for the Presidency and the Opposition’s Electoral Strategies

One of the opposition’s main aims was to prevent Morales from being elected President on the first ballot, since his chances of winning a run-off vote are considerably smaller. This goal had been evident in the strategies used to present candidacies and alliances, and in the campaign strategies of the different players who form the opposition to the incumbent candidate.

The incentives provided by the electoral system, combined with MAS’s hegemony, led to relatively good pre-election coordination among the opposition. As a result, the list of presidential candidates was (along with the 2005 list) the shortest in Bolivian history since democracy and elections were re-established: only seven candidates were running against MAS.

They were: Manfred Reyes Villa of Plan Progreso para Bolivia Convergencia Nacional (Progress Plan for Bolivia-National Convergence, PPB-APB), Samuel Doria Medina of Alianza por el Consenso y la Unidad Nacional (Alliance for Consensus and National Unity, UN-CP), René Joaquino of Alianza Social (Social Alliance, AS), Alejo Veliz of Pueblos por la Libertad y Soberanía (People for Freedom and Sovereignty, PULSO) Ana María Flores of Movimiento de Unidad Social Patriótica (Patriotic Social Unity Movement, MUSPA), Rime Choquehuanca of Bolivia Social Demócrata (Bolivia Social Democracy, BSD) and Román Loayza of the GENTE (People) party. Some potential candidates, such as former Presidents Carlos Mesa and Jorge ‘Tuto’ Quiroga (the latter being also the main opposition leader during the last four years), and a former Vice-president, Victor Hugo Cárdenas , are not in the running at all: Mesa decided not to run and instead supports Reyes Villa’s candidacy .

The opposition candidates with the broadest popular support were Reyes Villa (PPB-APB), Doria Medina (UN-CP) and, with support concentrated in Potosí, René Joaquino. The rest had little support and failed to win a seat in Congress or in the Senate at all.

Reyes Villa was Prefect of Cochabamba, but lost his job after the referendum in January. He is most popular in eastern Bolivia, in the ‘Half Moon’ region, made up of Beni, Pando, Santa Cruz, Tarija and Chuquisaca, which are considered opposition strongholds. Despite his dominant position in the city of Cochabamba, popular support in the rural areas of the department and especially in the wealthy coca-producing regions is with the governing party, and particularly with Morales, who was a coca leader before he became President.

Reyes Villa’s running mate was the former Prefect of Pando, Leopoldo Fernández, who was campaigning for the Vice-presidency. Choosing Fernández amounted to a political statement and a campaign stunt, since for over a year he has been held in the San Pedro prison in La Paz, accused by the government of being partly responsible for the El Porvenir massacre in September 2008, although his trial has still not begun. This, combined with the irregularities surrounding the events at El Porvenir and the appointment of a military officer close to the government as Prefect of the department, gives Fernández the aura of a persecuted politician (at least in certain circles), something that may have been very beneficial at the polls.

The PPB-APB campaign focused more on attacking MAS than on formulating its own proposals: it complained that the government was preventing Fernández from running a normal campaign; that there was political persecution of different opposition leaders; that civil servants and public funds were being used for the MAS campaign; and that the public communications media showed favouritism towards MAS.

Doria Medina is a well-known businessman whose flagship company, the SOBOCE cement company, is one of the biggest companies in Bolivia. Doria Medina received support from figures as important as Óscar Ortiz, President of the Senate. The UN-CP campaign focused on issues of productivity and development, specialisation in organic products and support for business people and micro-entrepreneurs. Doria Medina’s business experience and success were supposed to guarantee the quality of the party’s platform. UN-CP has attempted to establish a debate among the main candidates and, faced with MAS’s refusal, publicly offered organic eggs to Morales (‘to show the productive initiative of Bolivians… something that needs to be debated’). This has left the incumbent candidate in an uncomfortable situation, since he is not interested in a confrontation of this kind.

The most serious criticism of the MAS administration made by UN-CP was found in the complaint submitted to the United Nations –at an event headed by Óscar Ortiz– alleging that there had been 74 politically-related deaths during the term of the MAS government. In this regard, the greatest threat to the consolidation of MAS’s hegemony might be the intrigue surrounding the death of three Europeans at the Las Américas hotel in Santa Cruz at the hands of a police operative. Reports by Hungarian and Irish investigators, which speak of an ‘execution’, and the release of a set of video recordings that show police and government members in contacts with alleged terrorists, are deteriorating MAS’s public image.

The Battle for the Senate and MAS Strategies

The greatest counterweight to MAS’s power in 2005 was the opposition’s control of the Senate, where it held 15 of the 27 existing seats. The increase from three to four senators per region (for a total of 36) set a new stage and made it considerably more difficult to calculate where each side would find support.

Figure 4. Senators per region (2005)

| Senators | LP | CBB | ORU | PTS | CHU | SCZ | TJA | BEN | PAN | TOT |

| MAS | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 12 |

| PODEMOS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| MNR | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| UN | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 |

MAS: Movimiento al Socialismo; PODEMOS: Poder Democrático y Social; MNR: Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario; UN: Frente de Unidad Nacional; LP: La Paz; CBB: Cochabamba; ORU: Oruro; PTS: Potosí; CHU: Chuquisaca; SCZ: Santa Cruz; TJA: Tarija; BEN: Beni; PAN: Pando.

Source: CNI and the author.

A key initial goal for MAS in these elections was to obtain additional support to win a majority in the Senate. With the development of the campaign, this goal was extended to the achievement of a majority of two-thirds in both Chambers. This led its strategists to conduct an aggressive campaign, using a much larger budget than its rivals to bring in the rural vote and the most disadvantaged sectors in the pro-opposition regions of the ‘Half Moon’.

In its campaign, MAS put the emphasis on political and economic independence from the US and other developed countries, increases in Bolivian Central Bank reserves and a ‘process of (economic and political) change’ which, in its opinion, would favour the neediest members of society. MAS rhetoric was backed by the bonuses it had given out for maternity, education and the elderly, which have won it the sympathy of the most disadvantaged groups.

One of the regions where the battle was closest was Chuquisaca, where MAS had won the last elections throughout the entire rural area, but lost in the capital, Sucre. MAS’s strategy consisted of building hospitals and other infrastructure in the suburbs of the city and establishing its harsh criticism of ‘Sucrean racism’ as one of the main issues of debate in Chuquisaca. By doing so, MAS was attempting to increase its vote among the poorest suburban households.

To increase its rural vote, MAS has developed a policy to favour the ‘Chaco region’. The Chaco region is the part of Chuquisaca where prefect (regional governor) Savina Cuéllar –an indigenous opposition member– has the greatest support. This region, rich in hydrocarbons, is not limited to the department or region of Chuquisaca as such; rather, it spreads into Tarija and Santa Cruz, two opposition strongholds. However, despite its efforts, there are serious doubts regarding MAS’s effectiveness in winning over voters in Chaco.

In Pando (a region which, along with Beni, was the Achilles’ heel in MAS’s Senate bid in 2005), the replacement of Fernández by a pro-government military governor and the concession of land to emigrants from the western part of the country –where MAS has the most solid support– was to lead to better results for the governing party.

Results

Elections took place smoothly and practically without incidents, as assessed by several observation missions, including that of the EU, which, however, pointed out that MAS used public resources and institutions for its campaign.

The number of voters was the highest in Bolivia’s history, and results supposed a firm backing to President Morales. Data from the Corte Nacional Electoral (National Electoral Court, CNE), with a 91.4% count, indicate that Morales has been re-elected as President with 64.1% of the valid votes, and that MAS has obtained 26 out of 36 senators, and 85 out of 130 deputies, so it enjoys an ample majority of two-thirds in both Chambers.

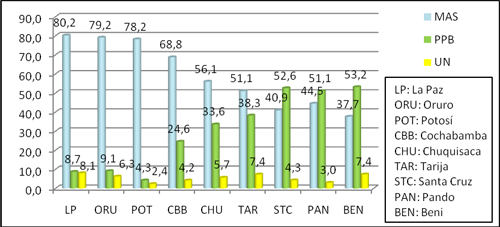

Figure 5. Distribution of the vote by departments

In aggregate terms, MAS increased by around 10% its results of 2005 (53,64%). In regional terms, MAS consolidated and widened its leadership in La Paz, Oruro and Potosí, maintained its advantage in Cochabamba, and revalidated its 2005 victory in Chuquisaca, which had become blurred in the different referendums which took place between the previous general elections and this one. Moreover, it achieved a majority, although a very small one, in Tarija, one of the ‘Half Moon’ regions, and it managed significant vote increases in the rest of eastern departments, although the opposition parties, taken together, still obtain more backing in Santa Cruz, Beni and Pando.

Conclusions: The Bolivian elections in December 2009 were special: they were the first under the New Constitution, the President was re-elected to another term, there was a new biometric voter registration system and voting from abroad was allowed for the first time.

In the last elections, Evo Morales’ MAS party had won a virtual monopoly on political representation from a very heterogeneous set of groups that tend to represent the most disadvantaged sectors of Bolivian society: indigenous, low-income and rural people. The MAS platform, backed by a campaign with abundant funding and combined with the bonuses given out by the government.

The main goal for MAS is to obtain additional support to win a majority in the Senate and, if possible, a majority of two-thirds in both Chambers. To accomplish this, it stepped up its efforts to capture the rural vote and the most disadvantaged sectors, especially in the regions where the opposition is strongest. Its strategy included policies that tend to develop a kind of ‘sub-regionalism’ favourable to the government (mainly in the Chaco region), replacing the prefect of Pando with a military governor who has close ties to the government, and granting land to emigrants from the western part of the country.

One of the opposition’s initial main goals was to prevent Morales from winning the presidency on the first ballot. The two main opposition candidates, Reyes Villa (PPB-APB) and Doria Medina (UN-CP), followed separate campaign strategies. The PPB-APB campaign focused on attacking MAS, while the UN-CP campaign put the emphasis on issues of productivity and entrepreneurship. The intrigue surrounding the deaths of three Europeans at the Las Américas hotel in Santa Cruz may present one of the greatest threats to MAS’s success at the polls.

It can be expected that the vote abroad will contribute favourably to MAS’s election results, but with a limited impact.

The MAS platform, backed by a campaign with abundant funding and combined with the bonuses given out by the government, allowed it to conserve and shore up its support. Results show a clear-cut victory of Morales, obtained with an unmatched participation rate. Morales was re-elected with 64.1% of the valid votes, and MAS won a majority of two-thirds in both Congress and the Senate. This ample majority makes it possible for MAS to govern virtually without opposition, and gives it a free hand to modify laws, the Constitution included. It also allows it to place an ample majority of pro-government professionals in other institutions, such as the judiciary.

Andrés Santana

Ph.D. in Political Science