Theme: The result of the Peruvian election has dispelled the main uncertainty present throughout the campaign: who will be the next president of Peru. However, it has also raised a large number of questions.

Summary: The results of the second round of Peru’s presidential election have dispelled the main uncertainty: who will be the next president of Peru. However, numerous questions remain, many of them involving the country’s internal politics and others relating to the multiple realignments that are now occurring in the region. Among the former, the greatest challenge facing the new government is governability on several fronts, starting with political and parliamentary alliances to ensure the continuity of the new government. Another major issue is the future of Ollanta Humala and his Nationalist Party –not an insignificant matter given the different paths that Hugo Chavez’s self-proclaimed Peruvian followers may take (some institutional, others more radical or violent)–.

From a regional perspective, the most interesting issues involve the more or less leading role the new government may wish to play in saving or rescuing the Andean Community of Nations (CAN), its backing of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the United States (and what kind of agreement it will pursue) and its degree of rapprochement with Brazil and Chile. At the same time, it is quite likely that the conflict between Peru and Venezuela will wind down in the immediate future, with the two ambassadors returning to their posts. In any case, this situation will make it possible to gauge how much room Hugo Chávez has to manoeuvre at the regional level, considering that he will soon be directly immersed in his own election campaign.

Analysis

Why Did García Win?

Without going into a detailed analysis of the results of the Peruvian election it should be said that several factors led to García’s win in the second round and that it is difficult to emphasise one more than the others. However, the question is worth asking, since in light of many analyses it would seem that García was the loser and, hence, Humala the winner. The following are the most important factors to bear in mind to understand the election result:

(1) In political and territorial terms, the Peruvian Aprista Party (PAP) was more firmly established than Ollanta Humala’s Union for Peru (UPP). While the APRA is a long-standing party with a well-oiled party machinery in terms of its presence throughout the entire country, the UPP essentially revolves around Humala. It should be borne in mind that Humala could not even run for the Nationalist Party –the ad hoc party he founded in 2005 to take part in this election– and had to borrow a different acronym (UPP) for his bid. Also, while the PAP had representatives at all polling stations, UPP supporters covered only 60% of the country’s polling stations. Unlike what occurred with Alberto Fujimori and Alejandro Toledo, on this occasion political organisation proved stronger than the (greater or lesser) presence of a charismatic leader.

(2) Beyond comparisons of the two candidates and attempts to determine which of them is more charismatic than the other (which does not make much sense), it is clear that García is a more experienced politician than Humala and has a greater command of political staging –and discourse–, in addition to the organisational backing mentioned above. In this regard, García’s proposals, revolving around his key campaign slogan, ‘A responsible change’ –‘Un cambio responsable’–, were more coherent and better articulated than his rival’s. Humala may be a politician with a bright future, as some Peruvian political analysts suggest, but he still has a lot to learn. His late arrival at the only televised debate between the two candidates and the incident with the Peruvian flag at the start of that debate bear witness to this. At the same time, he contradicted himself and lied many times throughout the election campaign.

(3) As a result –and despite the fact that the second round was a showdown between the two candidates who were most disliked among all those who took part in the first round– Alan García epitomises the old saying: ‘Better the devil you know…’. It is clear that the memory of his first, disastrous government came to bear, but it is also clear that some voters were influenced by memories of Fujimori (obviously, not those who voted for his political representatives) and the fact that he was an outsider who entered politics only to take power on a nationalist, populist and openly confrontational platform. It is also significant that the population of Peru is very young and that many new voters were children during the first García administration.

(4) The set of negative factors surrounding Humala became increasingly important when he became clearly linked to Hugo Chávez –his relationship with the Venezuelan leader, his trips to Caracas (including one during which he was virtually proclaimed Chavez’s candidate), suspicions about the provenance of the funding for his campaign– and, especially, when Chavez became openly involved in Peruvian politics, which President Toledo and candidate García called ‘meddling’ in the presidential campaign. Chávez’s recent appearances on Aló presidente, especially the programme broadcast from Tiahuanaco (Bolivia) in the company of Evo Morales before the election, clearly showed the extent of this involvement.

(5) Although nearly 50% of Peruvians live below the poverty line –and this is most visible in the departments in the south of the country–, the constant and continued macroeconomic growth in Peru in recent years has reached a not insignificant part of the population, notwithstanding the social and regional asymmetry it has caused. It was precisely this part of the population (including the urban middle classes) that saw the extravagant populism of Ollanta Humala as an attack on their own positions and on the continuity of the macroeconomic policies now in place. This explains why a significant number of voters opted to support García.

Peru: A Divided Society?

An idea that has lately become popular in political analysis is that countries split into two opposing halves after hard-fought elections. When certain elections end up being determined by a very small margin between two main options, it seems that these countries are inevitably considered to be immersed in irreconcilable conflict. There was talk of a divided Italy and now of a divided Peru; but there are not two halves in Germany and Bolivia, although obviously for different reasons: in Germany, because there is a broad coalition government of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, and in Bolivia because Morales won with 54% of the vote (paradoxically a very similar figure to that obtained by García). However, some say that on the night before the election on Sunday, 3 June, Peru was a single country and that 24 hours later a split had occurred; but in fact Peru’s social and regional divisions date back a long time.

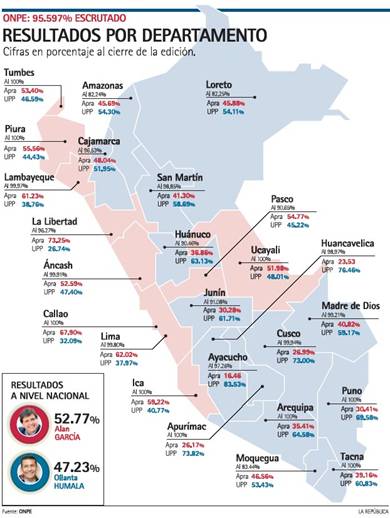

Figure 1.

An increasing number of Latin American presidential elections are finally decided in a second round. And where two-party politics is the norm (Chile and the US, for instance), it is not unusual for the electorate to vote in a relatively proportional way, especially in hard-fought elections. The lesser political and ideological differences in the pledges made to voters –compared to what tended to happen in the past– mean that elections are very often decided by a difference of very few votes between the main contenders (Costa Rica is a clear example of this). But does this justify talk of two different countries? Not necessarily.

Let us take a look at how Peruvians voted. In the first round, Ollanta Humala received 25.7% of the vote (slightly less than 3.8 million), compared with Alan García’s 20.4% (nearly 3 million votes). By contrast, in the second round, García received 52.8% (6.7 million votes) vs Humala’s 47.2% (6 million). This means that both in absolute numbers (772,000 votes in the first round to 705,000 votes in the second) and in terms of percentages (5.3% to 5.6%) the difference between the first and second rounds remained constant, although the positions of the two main rivals were reversed. Thus, while García managed to more than double his votes, adding 3.75 million, Humala only won 2.25 million additional votes.

With respect to the distribution of votes around the country, in the first round the UPP won in 18 departments, the PAP in six and the UN in one (Lima). In the run-off, apart from winning in Lima, the PAP edged out the UPP in the departments of Pasco, Tumbes and Ucayali, while the UPP won in 15 departments and the PAP in ten. As a result, nearly the entire coast (except for the south) was won by the PAP, while the interior (except for a central strip along Pasco and Ucayali –see the map above–) went to the UPP. At the same time, it is worth noting the very unequal distribution of the population in the various departments. While Madre de Dios has less than 100,000 inhabitants and Moquegua has only 160,000 (both won by Humala), Lima has a population of over 8.1 million.

The Challenges Facing the New Government

Although it is not facing two different countries, the new administration clearly understands that it must put forward very specific policies aimed at the poorest departments, especially (but not only) those located in the southern mountains –those least affected by the economic expansion of recent years–. Because of this, it would not be unreasonable to expect Humala to focus considerable energy on activating social protest movements, taking advantage of the difficult situation caused by poverty there.

Furthermore, too much emphasis is put on the new government’s weakness, as the PAP is only the second largest force in parliament (with 36 of 120 seats), behind the UPP, whose 45 deputies make it the largest group (though far from the absolute majority). At the same time, some insist that since Alan García received 24% of the vote in the first round, a large part of his second round win is the result of votes ‘lent’ to him. In this regard, Lourdes Flores of the National Unity party (Unidad Nacional –UN–, with 17 members in parliament), reminded García of the ‘conservative’ origin of a large part of his recent support in Lima. Though all this may be true, the main risk is in believing this particular situation will remain static, and forgetting that we are talking about the second round of a presidential election.

Faced with this situation, García has three possible courses of action available to broaden his power base and ensure the country’s governability: he can try to come to an agreement with the ‘leftist’ parties or co-opt a significant part of Humala’s supporters; he can shift to the right and make agreements with the followers of Lourdes Flores and Valentín Paniagua, among others; or he can try a third way, following the example of Kirchner in Argentina, and attempt to build his own power base.

Although a shift to the left may seem the easiest and most stable option from a parliamentary perspective, it is the most complicated overall: first of all, due to García’s virulent attacks on Humala and Chávez during the run-off campaign, and also due to the heterogeneous quality of the various political forces under Humala’s banner. However, apart from Humala’s initial acknowledgement of García’s victory and the best wishes he offered the winner, the two politicians have already arranged a meeting in which they will review some of the main issues on the domestic political agenda in the coming months.

Nevertheless, the more mature option appears to be a ‘stability pact’ with all the political forces in the democratic spectrum –something much easier to sell than a simple pact with the right–. This is an issue that the main Peruvian leaders have been talking about for quite some time, in light of what happened during the Toledo government. However, considering how soon regional and municipal elections are coming (this November), a combination of both scenarios would not be unrealistic.

In this respect, a good indicator of the direction things will take will be the names of Alan García’s first cabinet –starting with his choice of Prime Minister– and the political affiliation of the Speaker of the House. How many will there be from each party, and who will be chosen? And how many independents will be asked to head the various ministries? Valentín Paniagua has already been ruled out to head the cabinet and this is a good sign that APRA’s leader is broadening his political horizons. If APRA succeeds in its intention to hold the Speaker’s seat in Congress, despite being the second-largest parliamentary group, this will reveal what kind of alliances can be formed among the various political groups represented there.

The third way is much more complicated, since the PAP is not like Peronism, and García’s scope for manoeuvre is clearly limited. However, there are certain mechanisms that are sure to be quickly implemented, starting with the strategy aimed at splitting, co-opting and tempting members of Ollanta Humala’s parliamentary group to cross the floor. How many of Humala’s 45 deputies will remain loyal to their principles and how many will be tempted by power and money? For now, there are some rumbles of dissent among the elected members who belong to the original UPP and those who are Humala supporters.

The Challenges Facing the Opposition

Ollanta Humala and his heterogeneous group of followers (individuals and groups alike) face two major challenges: (1) managing to survive as a group and creating an organised party; and (2) how Humala will focus his politics in opposition –will he take the democratic path or will he take a much more radical and violent direction?–.

Forty-seven percent of the votes that Humala received in the run-off, and 30% percent of his first round votes, must be seen not simply as protest votes or votes arising from social unrest or anti-authority sentiment. In this regard, it must be borne in mind that Humala moderated his language as soon as he decided to run for office and then moderated it even further as the polls began to show he had increasing public support. However, his proposal to create a Popular Democratic Nationalist Front is, for now, receiving little backing, especially from the Peruvian left. Humala’s proposal to open up to certain left-wing groups, such as Patria Roja (Red Fatherland), the National Leftist Movement (MNI) and the Socialist Party was not well received by UPP president Aldo Estrada Choque, who dismissed the initiative as a failed idea. But within the Nationalist Party itself there are voices contrary to agreements with the ‘traditional left’, which they dismiss for not having received enough popular support in the latest election. Although it may sound contradictory, many of Humala’s parliamentary deputies, elected on UPP voting lists, lean more to the centre of the ideological spectrum than the rest of their colleagues, with the exception of the cocalero leaders.

Only MNI leaders have suggested they are open to the offer. For this reason, and regardless of whether or not it is possible to unite all the leftist forces under a single political umbrella, the 19 UPP deputies will have a great deal of influence in the new Congress. It is reasonable to wonder whether Humala will be able to remain moderate or whether he will return to the barricades and the etnocacerista roots he shared with his brother Antauro. For now, everything indicates that the radical path is the more likely. If he opts for it, will he once again make the reservist movement the focus of his actions? It is clear that either of these options will guarantee him support from some quarters and will alienate others, losing him a large part of the votes he received, especially if the government manages to implement public policies that effectively fight inequality.

Many adventures of this kind, regardless of how well they fared on Election Day, have more or less quickly come to nothing. An attractive and charismatic leader is not enough to form a party. The success that Toledo and Fujimori had at the polls was not enough to consolidate true, alternative power bases. In addition to an attractive leader, it is necessary to have attractive proposals and a significant organisation. The question Humala will have to answer in the coming months is whether an infusion of petrodollars will be sufficient to build a strong party and a political future which, if well channelled, could still last for a long time to come.

The International Context

Despite the campaign’s verbal virulence, which went as far as Lima and Caracas withdrawing their ambassadors, no one should expect Alan García to become the South American standard bearer against Chávez, unless there is some further direct provocation. García’s initial public statements clearly suggest he will focus on State policy rather than seek confrontation. However, Chávez was much more belligerent in his response: on the 11 June Aló Presidente broadcast he said that relations with Peru ‘are in the deepest freeze we can put them in and they are not coming out… unless the Government of Peru offers a proper explanation and its apologies to the Venezuelan people’. Chávez said he was bothered that Alan García had offended his ‘dignity as a man’, accusing him of beating women. He also reiterated his support for Ollanta Humala and pointed out that there were 1.2 million spoiled ballots ‘that international observers said nothing about’.

Anecdotes aside, and regardless of the repercussions of the election on Peruvian political life, it is clear that many factors were at play on the highly volatile Latin American geopolitical chessboard on election Sunday, especially since Venezuela’s withdrawal from the Andean Community of Nations (CAN) and the nationalisation of the oil and gas industry in Bolivia (see ‘Venezuela’s Withdrawal from the Andean Community of Nations and the Consequences for Regional Integration’, Elcano Royal Institute, parts I and II, available at ARI 54/2006). Victory by Humala would have enabled Chávez to set another pawn next to Colombia and further churn up the water in an unstoppable bolivarian flood. Although this was not the case, it does not mean that the waters have settled. It remains to be seen how each player will move his pieces in the moves to come. The presidential election in Venezuela, where Chávez’s re-election is at stake, will keep the President more in his own country and farther away from the regional scene for several months.

Will the CAN be one of the areas where García will choose to develop his regional policy? To the extent that he works to strengthen the Andean integration process, it will be necessary to seek greater rapprochement with Colombia, the other major player in the Community since Venezuela voluntarily dropped out. Apart from closer relations with Brazil –something already underway during the Toledo government, but which García wants to increase; so much so that his first visit as President-elect will be to Brasilia– it will be important to watch what gestures are made towards Chile. Closer relations between APRA and the Chilean Socialist Party are something to consider, since they would help reduce the bilateral tensions that now exist between the two countries. Should this be the case, Chile could distance itself somewhat from Bolivia, since Chile’s gas supply is the background to all these movements.

Conclusion: Although the presidential election in Peru answered the question of who would be the country’s next president, other questions remain unanswered. With the growing presence of Hugo Chávez in the campaign, the election took on regional importance, beyond its obvious local implications. The governability of Peru will therefore depend not only on what the government can do and on the political and parliamentary alliances that Alan García and the APRA can forge with other parties, but also on the capacity of Humala’s opposition forces to become a true alternative, requiring him to shift his radical stance a little closer to the centre. The consolidation of the García government –possible in so far as his policies are successful in the southern departments –will act as a considerable counterweight to Bolivarian expansionism.

Carlos Malamud

Senior Analyst, Latin America, Elcano Royal Institute