Theme1

According to civil society organisations, EU policies concerning vulnerable people in third countries –including migration, asylum and foreign aid– are on a regressive trend. This coincides with the rise of authoritarian-populist parties in European countries.

Summary

The EU’s reaction to the refugee crisis has been strongly condemned by NGOs. Restrictive migration policies and the containment of refugee flows in third countries, along with cuts and reallocations of aid budgets, are considered by civil society organisations as a step backwards in the EU’s course as an international normative power. As Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart indicate, these policy trends can be related to a ‘cultural backlash’ exploited by authoritarian-populist parties and leaders that explicitly reject global solidarity and other values that used to form part of the political consensus in European liberal democracies. After a decade of crises in Europe (the financial crisis, the refugee crisis and Brexit), this paper summarises the evolution of international solidarity policies (migration, asylum and international aid) in the EU and explores their link to the increasing populist influence on its member States’ politics.

Analysis:

The Syrian civil war generated almost 6 million refugees between 2011 and 2015, many of whom attempted to find protection and new prospects in central and northern Europe. This came on top of migratory pressures from other Middle-Eastern and North-African (MENA) countries following the ‘Arab Springs’, and from Sahel countries facing recurring humanitarian crises, and gave rise to what was known as the 2015 refugee crisis.

Over 100 European NGOs adopted in 2016 a joint statement strongly criticising the management of this crisis by the EU’s Institutions and a broader political shift in EU foreign action. According to these organisations, border control was prioritised over other approaches that have cemented the EU’s historical reputation in foreign affairs, such as the defence of human rights and international law. They even announced that the EU was about to embark on a dark chapter in its history.

The EU’s political shift denounced by NGOs is often referred to as ‘fortress Europe’. This term has been used for decades to criticise the EU’s protectionism in migration and other policy areas like trade, and it has now become even more controversial as it metaphorically (and sometimes literally) connects with the discourse of authoritarian-populist parties, also known as national-populist or radical-right parties.

According to Norris and Inglehart’s (2019, p. 230) categorisation of parties, authoritarian-populism calls for power to return to ‘ordinary people’ in opposition to the so-considered corrupt elites, and holds policy positions that reflect conformity with tradition, collective security and loyalty towards group leaders. Another variety of populism, libertarian-populism, combines anti-elitism with policy positions in favour of personal freedoms and pluralism. However, when considering the number of parties in each category, populism in Europe is mainly authoritarian.

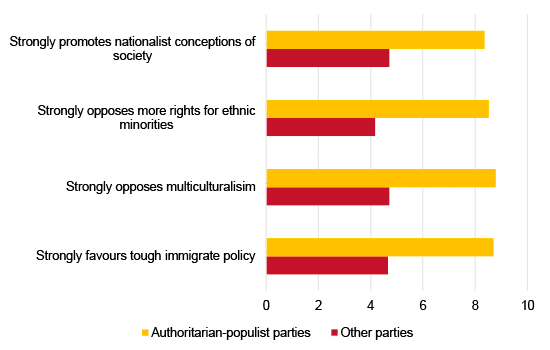

Four out of the seven variables considered by Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart to operationalise the authoritarian-libertarian cleavage relate to attitudes towards foreigners: (1) nationalist rather than cosmopolitan conceptions of society; (2) support for tough immigration policies; (3) opposition to the integration of immigrants and asylum seekers; and (4) opposition to more rights for ethnic minorities. The other three variables considered, which connect more directly to the term ‘authoritarian’, are: (5) an emphasis on tough anti-criminal measures over the protection of civil liberties; (6) opposition to liberal policies regarding social lifestyles (eg, homosexuality): and (7) opposition to the expansion of personal freedoms and democratic participation.

These features can be operationalised using data from expert surveys like the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) , which was launched in 1999 with a focus on European integration, one of the issues politicised by authoritarian-populist parties in several EU countries. Figure 1 shows the CHES indicators that measure anti-cosmopolitan features in European parties and compare authoritarian-populist thinking with that of other parties.

According to Gómez-Reino (2020), the rejection of foreigners and multicultural societies is the core ideology of these parties, which tend to succeed under very similar political slogans such as ‘Our Country First’ or ‘Us First’ and reflect their criterion for resource allocation. From this perspective, as authoritarian-populist parties gain political influence, less resources are expected to be allocated for the benefit of people different to ‘us’, be ‘they’ migrants, refugees or foreign aid recipients. Therefore it is worth analysing the link between the rise of this political movement and trends in foreign policy and domestic policies involving foreigners. Data on international-solidarity policy trends and populist political influence are provided in the following sections, which also explore the links between the two phenomena.

Decreasing international solidarity

International solidarity policies can be defined as governmental action with a direct and positive impact on vulnerable people in foreign countries, thus including development cooperation, asylum, and migration. Although they might be influenced by diverse motives, including security interests or compliance with international norms, they are policies with costs and benefits separated across borders and therefore likely to be supported by international solidarity arguments. The following indicators related to migration, asylum and foreign aid have been selected to capture international solidarity trends in European governmental action: the Official Development Assistance (ODA)/GNI ratio; the acceptance share of family reunification applications by migrants; and the acceptance share of asylum applications by refugees.

It is worth noting that the policy indicators considered in the categorisation of authoritarian-populist parties do not cover aid policy or international cooperation in more general terms. However, the indicators that refer to broader political considerations, such as cosmopolitan conceptions of society, do clearly connect with the leitmotiv of development aid. Questions about how these parties and leaders influence public policy usually refer to migration, which is the most evident programmatic common feature of this movement, but from this broader political perspective it would be of enormous interest to measure the policy positions of parties considering international cooperation and the multilateralism of development aid.

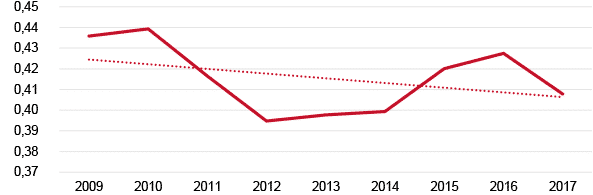

ODA is defined as concessional funding (grants and soft loans) provided by governments of richer countries to promote the economic development and welfare of poorer countries. The ODA/GNI ratio is a long-standing measure for international solidarity and is often assessed against the 0.7% benchmark set by the United Nations in the 1970s and renewed on several occasions since then. In the past decade, the average ODA/GNI ratio among EU member States has decreased.

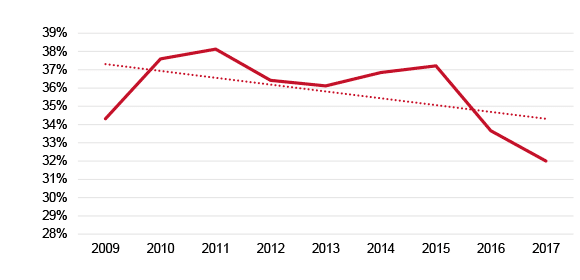

‘Refugee status determination’ is the legal or administrative process by which governments determine whether a person is considered a refugee and can receive legal protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention, along with further benefits. Despite the inflow of refugees in Europe, the share of positive resolutions on asylum applications and refugee status determination has decreased in the past 10 years.

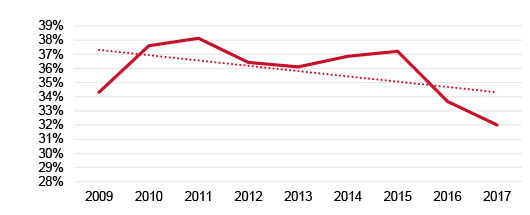

The variation in overall migration inflows is related to the awarding of work permits, which in turn depend on the needs of the host country’s labour market. On the contrary, family reunification permits are based on migrants’ rights and often favour the younger and elder members of their families, with little effect on the labour market and potential consequences on the host country’s public expenditure. The awarding of this kind of permits by EU member States has also shown a negative trend in the last decade.

Increasing political influence of authoritarian-populist parties

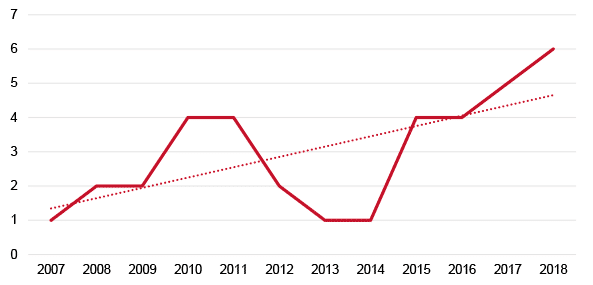

While the international solidarity indicators presented above show a negative trend in the EU, authoritarian-populist parties explicitly rejecting such values have increased their influence on member States’ politics. Drawing on Gómez-Reino’s (2020) study on anti-foreign-aid narratives, a measure of this influence is provided in the following table by showing the number of the governments relying on authoritarian-populist support.

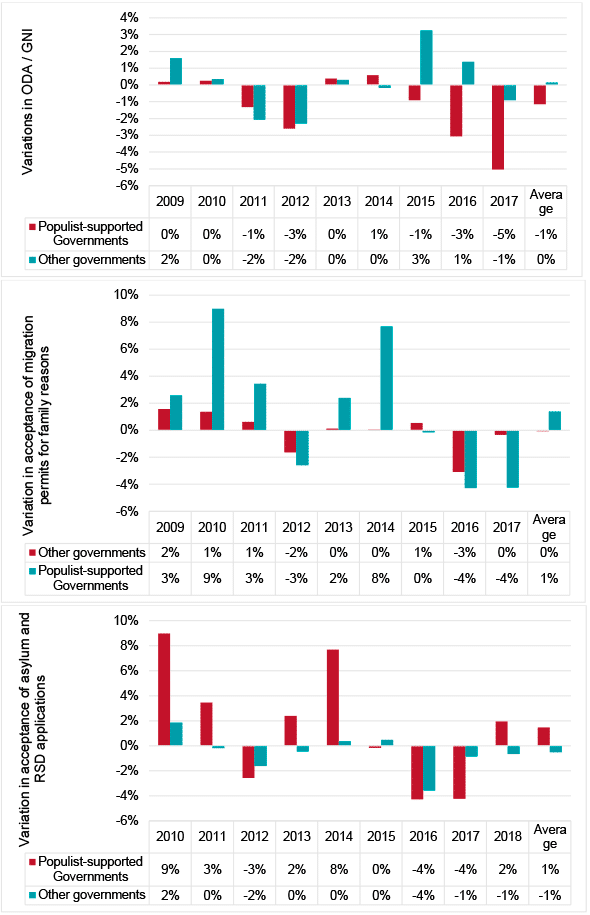

In order to explore the link between growing populist influence and regressive policy trends in international policies, a comparative analysis is presented in Figure 6 below. The graphs show variations in the selected policy indicators in countries and years which fall under populist political influence, on the one hand, and those which do not, on the other. Such comparisons indicate that the direct or indirect participation of authoritarian populist parties in European governments do not make a difference in the evolution of international solidarity policies. Negative variations are higher under populist-influenced governments, but so are positive variations. Over the decade, such variations recorded a negative average only for the ODA/GNI ratio, while the acceptance rates of family reunification and asylum applications were positive on average.

Conclusions

The indirect influence of authoritarian populism on public policies

In summary, several indicators show that international solidarity policies in Europe have followed a negative trend over the past decade. These data are consistent with the NGOs’ discourse, denouncing the way that EU Institutions managed the 2015 refugee crisis and a broader change in their foreign policy focus, from the defence and dissemination of cosmopolitan values to border controls. This approach, which is often referred to as ‘fortress Europe’, connects with the discourse of authoritarian-populist parties, which display several anti-cosmopolitan features. In fact, the political influence of these parties in Europe, measured as the number of governments that depend on their support, has increased, while international solidarity policy indicators have decreased.

However, a first comparative analysis shows that causality links cannot be established between the two trends. This might be related to an aspect of authoritarian-populist parties and their leaders that is often highlighted by analysts: their lack of experience in public administration and the difficulties they encounter in implementing policy changes when leading or participating in government formation. At the same time, several scholars highlight that they can exert a strong influence in policy outcomes in an indirect manner. By focusing on public debates and controversies instead of actual policy, and by providing rhetoric rather than government programmes, they increase the salience and polarisation of certain issues and condition the position of mainstream partners on these issues. The contagion of conservative parties in policy areas like migration and EU integration has been extensively analysed, but it would also be worthwhile analysing how left-wing mainstream parties and leaders avoid being vocal about issues that have been previously politicised by authoritarian-populist parties.

Aitor Pérez

Senior Research Fellow, Elcano Royal Institute | @aitor_ecoper

References

Gómez-Reino, Margarita (2020), ‘Nationalism in the European arena, “We First” and the anti-foreign aid narratives of populist radical-right parties’, in Iliana Olivié & Aitor Pérez (Eds.), Aid Power and Politics, Routledge, London, p. 272-284.

Norris, Pippa, & Ronald Inglehart (2019), Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

1 This paper forms part of a joint Elcano-UNED project on ‘the changing politics of international solidarity in Europe’ that covers the evolution of public preferences, party competition and policy performance in the field of migration, asylum and foreign aid. The project was launched by means of a research workshop in which this paper was discussed. The author is grateful for comments on the paper by Beatriz Acha, Sandra Bermúdez, Margarita Gómez-Reino, Patricia Lisa, Hugo Marcos, Iliana Olivié, Carmen González and Anna Terron, and for insights on the overall research provided by Pippa Norris, Charles Powell and Gustavo Llamazares during the workshops opening session.