Theme

The high synchronisation of political cycles in Latin America –from dictatorship to democracy, from centre-right/right to centre-left/left governments– can be traced to the high synchronisation of economic cycles, largely explained by common external factors.

Summary

In the last 50 years, political cycles –the alternation in power from military dictatorships to democracies, from elected centre-right governments to the ‘Pink Tide’, from the end of the ‘Pink Tide’ to the vote against incumbents of the last decade– display a very high synchronisation. This is not fortuitous but responds to highly synchronised economic cycles in Latin America, largely driven by external factors. These cycles are reflected in political changes that suggest an ‘economic vote,’ in which citizens punish or reward governments according to the performance of the economy.

Economic cycles are also manifested in indicators of democratic functioning. Trust in institutions, support for democracy, the degree of ideological polarisation, political fragmentation and governance fluctuate cyclically, deteriorating in periods of stagnation or crisis, which indicates that the health of the democratic system is intimately linked to economic performance.

This historical pattern suggests that the political setbacks observed in times of stagnation or crisis are not irreversible. If an economic recovery materialises, it opens the possibility of reversing the negative trends of the last decade of economic stagnation, once again strengthening democratic institutions and citizen trust. If the historical pattern repeats itself, it is a promising sign for the future of democracy in the region.

Analysis[1]

Should we be surprised that the military dictatorships of the 1970s began to collapse one after another in the early 1980s, paving the way for a process of widespread democratisation in the region? Should we be surprised that, towards the end of the 1990s, the elected governments –mostly centre-right and champions of the ‘Washington Consensus’– that governed the region fell apart like dominoes in the early 2000s, giving way to the ‘Pink Tide’, that is, to the coming to power of centre-left or left-wing parties? And what about the successive re-election of these governments in the first decade of the 2000s, or the abrupt end of the ‘Pink Tide’ starting in 2014? Should we be surprised by the loss of support for democracy, the growing distrust of elites and the consequent polarisation, political fragmentation and complex governance that have been observed in the region in recent years?

The short answer is no. In this analysis, we explain how these phenomena are part of a cyclical pattern that links economic ups and downs with political changes.

1. Lessons from modern history

Political science research has long documented the existence of an economic vote. Specifically, there is abundant evidence that voters in democratic countries systematically re-elect incumbent governments in times of economic boom and dismiss them in times of economic slowdown, recession or crisis.

There is also ample evidence that economic fluctuations in Latin American commodity-exporting countries are largely explained by common external factors, and consequently economic booms and busts in the region’s countries tend to be highly synchronised (Figure 1).[2]

It follows that countries with synchronised economic cycles should also display synchronised political cycles.

This analysis presents 50 years of historical data that support the hypothesis that political cycles in Latin America are highly synchronised, that the synchronisation is a reflection of the synchronisation of economic cycles, which in turn is largely determined by the whims of external factors.

1.1. 1974-90

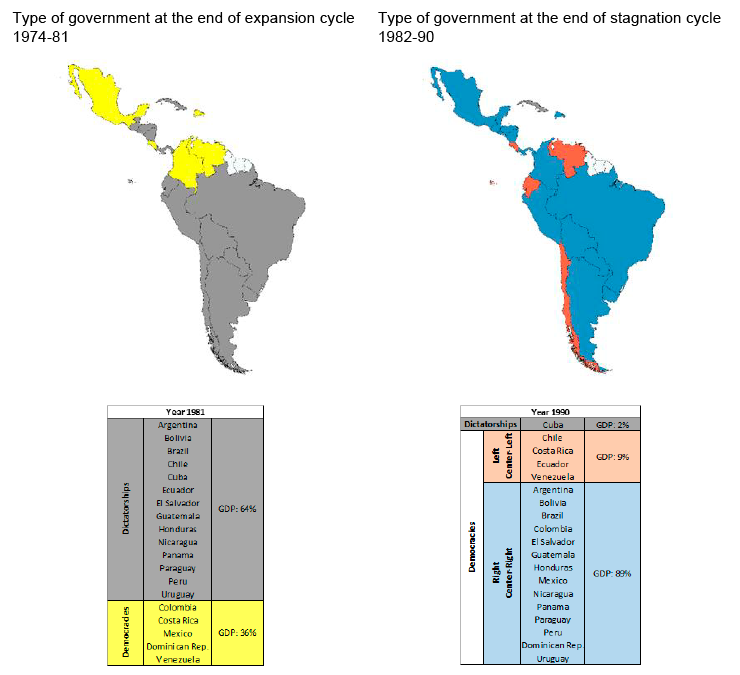

The period between 1974 and 1981 was expansionary for Latin America (Figure 2a). The region grew at an annual rate of 4.3%, compared with a historical average of 2.5% per year, resulting in strong growth in per capita income.

When oil prices rose sharply in the early 1970s, the resulting ‘petrodollars’ were recycled to emerging economies –and in massive amounts to Latin America– in the form of bank loans from international banks. These capital inflows financed huge increases in public spending and widespread real-estate booms, fuelling an economic bonanza that propped up the military dictatorships that were commonplace in the region at the time. Indeed, at the end of the expansionary cycle, in 1981, 80% of Latin American governments were military dictatorships (Figure 2b). At that time, the reestablishment of stability and order by authoritarian regimes was credited with the economic boom.

And then came the ‘Volcker shock’. The then Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker, orchestrated a sudden hike in interest rates to 20% per annum to break an inflationary spiral, then hovering around 15% per annum.

This was a treble whammy for Latin America: the US entered a deep recession, commodity prices plummeted and the abundant capital inflows into the region of the expansionary period came to a sudden stop (in fact, they began to flow out of the region), attracted by the high yields offered by US dollar-denominated instruments. The result was a ‘lost decade’ of economic stagnation, in which many countries suffered a collapse of output, along with currency, debt and banking crises (Figure 2a).

The political flip side of the economic stagnation and crises was widespread social unrest, which resulted –helped in the late 1980s by the fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of the Cold War and the end of US support for the region’s military regimes– in the period 1982-90 in the fall of all the region’s dictatorships (except Cuba’s). These were replaced by democratically-elected governments, mostly centre-right/right (Figure 2b).

The centre-right governments changed the prevailing economic paradigm of import substitution, high government intervention and over-regulation to the so-called ‘Washington consensus’: fiscal discipline, low inflation, trade and financial liberalisation, privatisation and deregulation.[3]

Figure 2. Economic cycle and electoral cycle in Latin America, 1974-90

2b. Electoral cycle

1.2. 1991-2003

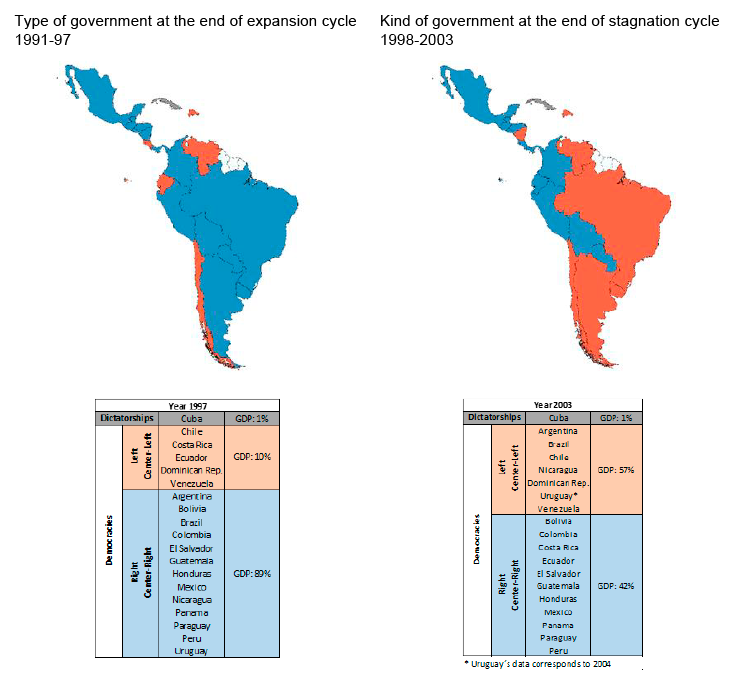

In the early 1990s, with the advent of new democratically elected governments, the resolution of the debt crisis through the ‘Brady Plan’ (so called because it was an initiative of the then US Secretary of the Treasury Nicholas Brady), and the return of low interest rates in the US, Latin America was again flooded with foreign capital, this time mostly in the form of international public and private sector bond issues, mostly denominated in US dollars.

The consensus at the time was that these capital inflows driven by international bond markets would bring market discipline to a region always prone to profligacy (ie, only solvent countries and companies would be able to borrow). The ensuing boom in the region between 1991 and 1998 (Figure 4a) was interpreted by many experts as the ultimate proof of the effectiveness of the ‘Washington Consensus’ policies. The combination of sound and credible policies and democratisation seemed to have paid off.

Then came the Asian crisis of 1997 and the Russian default of 1998. The latter prompted a dramatic drop in capital flows to the region that caused growth in Latin American countries to plummet (Figure 4a). Once again: recession, depression, currency, public debt and banking crises, with Argentina in 2001 being the most vivid memory of this period.

In the early 2000s, in the midst of economic malaise and social discontent as a result of stagnation and crises, centre-right governments began to fall like dominoes and were replaced by centre-left –or, in some cases, populist– governments in most of Latin America (Figure 4b).

Figure 3. Economic cycle and electoral cycle in Latin America, 1991-2003

3b. Electoral cycle

1.3. 2004-17

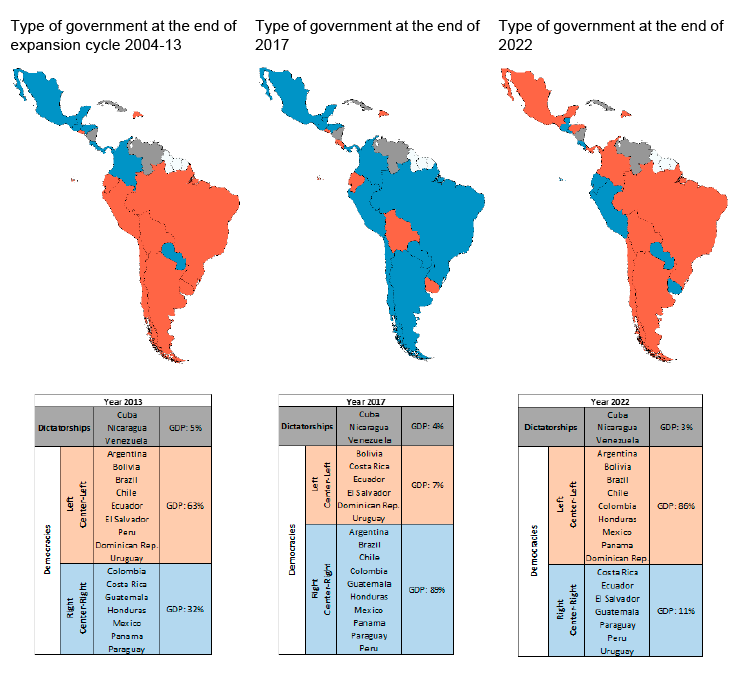

The new generation of centre-left governments did not repudiate the previous commitment to fiscal discipline, low inflation and open markets. On the contrary, they built on them and implemented massive social redistribution programmes (mostly targeting the poorest, as was the case with Bolsa Escola in Brazil and Progresa in Mexico). These programmes were financed by the commodity price boom –which began in 2003 and lasted until 2013 and became known as the ‘commodity super-cycle’– and a new wave of capital inflows that peaked in the aftermath of the global financial crisis as investors in developed countries sought alternatives to the low returns on US dollar instruments. Once again, high commodity prices and abundant and cheap international capital fuelled a decade-long economic boom (Figure 4a). And again, the governments of the time attributed their success to the policies of the prevailing paradigm, which in this case combined economic orthodoxy with redistribution.

And then came the Eurozone crisis and a sharp economic slowdown in China, a collapse in commodity prices and a sudden stop in capital inflows to emerging markets as investors sought refuge in safe assets. Starting in 2014, growth in Latin America cooled significantly (Figure 4a), with some countries faltering and others falling into deep recessions.

After a decade of stellar growth and bright expectations, governments had once again fooled themselves and voters into believing that it was exclusively their own actions that were behind the boom. The frustration of those expectations quickly turned into social discontent and led to massive street protests convened through the social media. In some countries, high-profile corruption scandals added fuel to the fire. Unrest in Latin America arose at a time when the foundations of the international liberal order were beginning to weaken as a result of the rise of nationalist/populist –in some cases also authoritarian– movements in the US and Europe. The election of Donald Trump as US President in 2016 and Brexit a few months earlier are symbolic of the times.

The political reflection of economic stagnation was the return to centre-right and right-wing governments (Figure 4b). More precisely, it was a repetition of past cycles: a repudiation of incumbents, regardless of their orientation. It is only because the golden decade 2004-13 was dominated by centre-left and populist governments that the phenomenon we observed in the electoral cycle 2014-17 is interpreted as a turn to the right.

Figure 4. Economic cycle and electoral cycle in Latin America, 2004-22

4b. Electoral cycle

1.4. 2017-22

The sequence of elections between 2014 and 2017 that brought about the shift from left to right, was not followed by a period of economic expansion. On the contrary, in the following five years (2018-22) the region continued to grow at mediocre rates and stagnation was persistent. Neither commodity prices nor capital inflows to the region managed to recover, which was compounded by the COVID crisis (Figure 4a).

Given the continued economic stagnation, ruling parties continued to be punished at the ballot box. The centre-right and right-wing governments that emerged in the previous electoral cycle failed to meet voters’ expectations, and in the elections of this period (2018-22) they were defeated at the polls and replaced by centre-left and left-wing governments, the most salient examples being the victories of AMLO in Mexico (2018), Alberto Fernández in Argentina (2019), Pedro Castillo in Peru (2021), Boric in Chile (2021), Petro in Colombia (2022) and Lula in Brazil (2022), as shown in Figure 4b.

1.5. 2023-26

The 2023-26 period is only halfway through. Therefore, no firm conclusions can be drawn until a new full cycle of elections is completed. In 2025 there will be presidential elections in Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador and Honduras, and in 2026 in Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica and Peru.

According to International Monetary Fund projections (Figure 5) in 2022 the prolonged period of stagnation in GDP per capita observed since 2014 –which has earned it the name ‘the new lost decade’– could have come to an end.

If the beginning of a new expansionary period as of 2023 is confirmed, the pattern we document in this analysis between the economic and political cycle suggests that incumbents that came to power in the previous period (2017-22) and as the expansionary cycle consolidates, could begin to be re-elected. This phenomenon was observed in the 2023-24 presidential elections. Of the nine presidential elections, five were won by the ruling party, with Claudia Sheinbaum’s victory in Mexico being the most emblematic case, and four were won by the opposition, the most salient case being the victory of the Frente Amplio in Uruguay.

2. The economic and political cycle in Latin America: beyond elections

The electoral cycle is not the only relevant political dimension associated with the economic cycle. Other political manifestations such as support for democracy, trust in the political system, the ideological polarisation of the electorate, political fragmentation and governance, also exhibit a clear pattern of cyclical behaviour related to the economic cycle.

The meagre growth of the last decade displayed an average GDP growth rate similar to that of the previous period of stagnation between 1999 and 2003 (Figure 4a). A similar cycle is observed in voter support and satisfaction with democracy, which exhibits slightly lower levels than those recorded during the 1999-2003 stagnation (Figure 4b).

This cycle is also observed in the levels of trust in the political system (parties, president and government), which have fallen significantly since the peak of the economic boom in 2013, to levels similar to those prevailing in the previous economic stagnation period (Figure 4c). An analogous phenomenon occurs with the ideological polarisation of the electorate, as voters move to the extremes to the left and right during periods of stagnation (Figure 4d), with political fragmentation increasing (Figure 4e) and complex governance that also increases in periods of stagnation (Figure 4f). All these indicators of the functioning of democracy and the political system exhibit cyclical behaviour in tandem with the economic cycle, and the current levels are similar to those observed during the 1999-2003 stagnation period (Figures 4e and 4f).

In summary, the current political regression is not only related to the economic cycle but also takes us back quantitatively to the regression levels observed during the stagnation period that preceded the stagnation of the last decade, that of the five years between 1999 and 2003. If the historical pattern repeats itself, the evidence presented allows us to conclude that these phenomena could have a cyclical component that will eventually be reversed when the region’s economy gets back on track. This is a promising finding.

Figure 6. Economic cycle and political cycle in Latin America, 2003-22 (simple average of countries)

Conclusions

The history of Latin America reveals that a highly synchronised economic cycle of countries in the region has been a determining factor in the cyclical rotation of power (between dictatorships and democracies, between parties to the left and right of the political spectrum, and between incumbent governments and the opposition), which is also highly synchronised.

Moreover, political regressions (loss of support for democracy, growing distrust of political elites, intensification of ideological polarisation, fragmentation of the political system and complex governance), are also cyclical phenomena largely governed by the economic cycle.

Far from being an inescapable destiny, this pattern opens the door to new scenarios of democratic renewal for the region, to the extent that the economic recovery and the end of the stagnation of the last decade may drive the reversal of these trends.

[1] This analysis is an extension and update of Talvi (2016).

[2] US and Chinese growth, commodity prices, and international financial market conditions explain 75% of the fluctuations in Latin America’s GDP.

[3] The ‘Washington Consensus’, a term coined by the economist John Williamson, is a set of economic policy recommendations that emerged in the 1980s, linked to the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the US Treasury Department.