Executive Summary

This report aims to provide a structured overview of the issues that need to be addressed in order to overhaul Spain’s foreign policy strategy. It is directed at all those who play leading roles in the defence and projection abroad of Spain’s values and interests. Its novelty lies in Spain’s lack of a tradition in drawing up papers such as this, since the usual practice has been to focus on the short term and to disregard the need for both public doctrine and planning. Nevertheless, it comes at a time when a more strategic outlook has begun to emerge in other fields, while there is a growing awareness that Spanish foreign policy has lacked any clear strategic guidelines since the country’s successful and full insertion in Europe and the world. The absence of clear guidelines has been aggravated during the crisis as a result of the declining resources available for foreign policy and of the public’s disillusion with the role Spain might play in the globalisation process. Furthermore, the large-scale changes and uncertainties on the international and European scenes make an exercise of this nature even more advisable.

The paper is not rigidly prescriptive but rather provides general guidelines and some specific suggestions based on the overriding premise that a country’s collective values and ideas must necessarily be reflected in its foreign policy and external action (two terms here considered to be virtually interchangeable when looked at from a strategic perspective). It starts by identifying Spain’s fundamental values and interests, which determine the international action necessary to achieve them. It then looks at the country’s position in the complex world context, identifying the priorities to be pursued and where and how to do so, including an analysis of the means available and a proposal on designing foreign policy.

Spain is currently experiencing difficulties but its contemporary history also provides a decisive story of political, social and economic success. The country’s collective vision may in turn require renewal, but the essential components of the Spanish model remain as follows: (i) democratic coexistence; (ii) security; (iii) sustainable prosperity; and (iv) culture and knowledge. This widely shared consensus provides a basis on which to build a sound foreign policy.

The world is increasingly multipolar in economic terms and apolar politically, and its societies are more dynamic and well informed, but also more unequal and older. The difficulties in coping with globalisation should encourage all nations to cooperate but current trends do not suggest the emergence or consolidation of effective multilateral systems. In this context, Europe is a region with specific difficulties due to its weaknesses in terms of demography, energy resources and the economy, and its diplomatic and military fragmentation. The construction of a united Europe provides the best response to these challenges, but the EU is vulnerable: its currency has unstable foundations, its legitimacy is questioned, its common foreign and security policy is still fragile, and it faces an unstable world that is relatively hostile to its values. This should encourage its member states to foster an ambitious process of political integration, but current trends suggest that progress will be slow.

Spain’s place in this scenario is also difficult. The prospects for its international presence are less favourable than in the last quarter of the 20th century, when it managed to fully normalise its foreign policy. However, it is also true that, in contrast to its isolation in 1976, Spain today is well integrated in the world. In any event, Spain faces both significant risks and valuable opportunities. Its weaknesses and threats relate to its economy, politics, demography, energy and the environment, security, the competitiveness of its production model and the quality of its education and scientific-technological systems. In the specific field of foreign policy, the country has been unable to make better use of its geopolitical potential and its soft power, exerting less influence than warranted by its objective international presence. But Spain also has strengths and opportunities on account of its high level of socioeconomic development, political-institutional stability, sound external projection in the business world, strong appeal and a global language. In addition, it has a highly valuable geographic-historical position, is well integrated in the EU and the Atlantic space, and has an extensive external network as well as armed forces and a development cooperation system with the potential to play a leading international role.

Based on the premise that Spain’s external action should help it achieve the essential aims of its aspirations as a country, this Report has identified six strategic objectives, three of which relate to fulfilling Spain’s own domestic aspirations (democracy, security, and competitiveness and talent) while the other three are more connected to foreign policy (European integration, international responsibility and influence).

European integration remains the main strategic commitment for Spain’s foreign policy. The EU’s future now entails consolidating the euro, maintaining internal cohesion and regaining public support, and in becoming an axis of world power. As the fifth-largest member state and by establishing close relationships with the EU’s institutions and other states, Spain must step up its efforts to shape the process according to its preferences or risk being left behind. To this end, it must develop its own narrative on the type of federalising integration that best suits it and take a more proactive role, generating its own ideas on the construction of Europe as a whole and on the various common policies. In addition, it must pay more attention to the quality of its representatives in Brussels and better integrate its players to define the nation’s position, reinforcing the role of the Spanish Parliament.

The second objective is to define and project an international identity based on the model of advanced democracy that Spaniards aspire to have. To this end, the authorities must undertake, and society as a whole must demand, a more explicit defence of democracy and human rights in the world. The corollary of this attitude involves actively supporting the generation of multilateral governance systems based on shared legitimacy, respect for international law and efficiency. But reinforcing the relationship between foreign policy and democracy should not only be directed from the inside outwards but also, and perhaps principally, should involve knowing how to make the most of the potential that a certain type of external action has to improve the quality of democracy at home. On the one hand, this means putting the focus on the public, empowering them in the face of globalisation, encouraging them to participate more in defining how Spain connects with the world and, beyond its borders, providing them with assistance and protection. On the other hand, it is necessary to be clearly associated with other advanced democracies that share the same cosmopolitan values and to make Spain’s territorial diversity more explicit in its external projection. This will help strengthen the public’s identification with the idea of domestic coexistence within Spain, which some currently feel distanced from.

In the field of security, the Report fully agrees with the content of the National Security Strategy approved in 2013, which means that the challenge for foreign policy is to contribute to the synergy and coherence of the action contemplated in it. As for defence, multilateral and bilateral commitments to contribute to peace and international security must be adapted to the new strategic context. The limited resources available must also be taken into account, although military capacities that allow Spain to interoperate with its allies should be maintained. In the diplomatic arena, action on non-proliferation, disarmament and arms control must be integrated, and international regulation of new threats encouraged. Likewise, efforts should be made to integrate external action on public safety, intelligence, humanitarian emergencies and pandemics. Regarding natural resources, and especially energy, there is a need to diversify the sources of supply, promote links with the European markets, monitor transport security and innovate in order to reduce external dependence. Finally, ensuring the effective protection of Spaniards abroad requires a review of consular operations and attention to the needs of businesses abroad, with a particular focus on SMEs.

The objective of competitiveness and talent makes reference to the important contribution that external action can make to improving economic and financial stability, changing the economy’s model of international integration and ultimately promoting, through education and research systems that are better connected to the world, a more dynamic, innovative and sustainable Spain. To achieve stability requires, on the one hand, speeding up the construction of a genuine economic and monetary union. On the other hand, it is necessary to use global governance forums to achieve a better framework for financial regulation, investment protection, the fight against tax fraud and the coordination of macroeconomic policies. In terms of the strategic planning of the qualitative leap required by the Spanish productive model, the aim must be to diversify exports, facilitate the access of more companies to global value chains, improve connection infrastructures and clearly advocate innovation. In fact, internationalising the research and development system, through action in the spheres of education, science-technology and attracting talent, is the best way to increase competitiveness and welfare in the long term.

The decision to add responsibility as another central objective of strategic external action is justified because the Spanish public share the value of solidarity and also because contributing to its content helps to ensure a better management of the global affairs that undoubtedly affect them. In this respect, policies concerning human rights, development cooperation, humanitarian aid and the generation of global public goods –especially in the fight against climate change– must be integrated. Spain, in line with the EU, can take a more proactive attitude in defining global agendas on these issues. Within its borders, the challenge is to integrate the different agents of external action on these issues. In this respect, Spain needs to go beyond mere coordination and define new strategic relations by identifying the added value of each of those involved. The objective of responsibility, and especially cooperation policy, requires appropriate means –qualified human resources, a reversal of the decline in the budget for development cooperation, and a greater geographical and sectoral concentration of the latter– and the development of new instruments.

The final objective advocates the need to reinforce international influence through strong external relations and a better use of the key components of soft power. In the multilateral domain, Spain can play an important role in solving global problems since its international identity arouses neither hostility nor rejection. In bilateral and regional relations, better use must be made of strategic alliances through various combinations and three-way relations. Moving beyond the diplomatic to the interpersonal sphere of action, current emigration flows can help to extend Spain’s networks abroad while there are underutilised opportunities to turn Spain’s appeal to tourists, students and immigrants into a better means of political, cultural and economic projection. Knowledge of Spain’s language and culture must also be encouraged, but without forgetting the country’s internal diversity or the fact that it shares a global language with more than 20 other countries. In terms of reputation, Spain must identify, highlight and pursue the elements of the international image to which its society aspires. And, finally, it must not forget that influence goes hand in hand with predictability and continuity.

These objectives must be developed at different levels. Spain supports multilateralism by conviction, but also due to its medium diplomatic size, its condition as a European country and its deep involvement in globalisation. Nevertheless, much of its external action needs to be developed bilaterally and unilaterally, through the many policies to be developed domestically to improve the country’s internationalisation. In addition, synergies and the division of labour should be clarified in order to establish which components of external action can be developed to a greater or lesser extent through the EU and which must remain Spain’s responsibility.

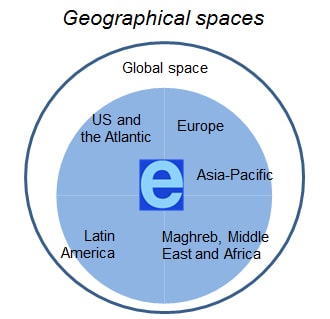

Similarly, the six strategic objectives should be pursued in different geographical areas. This Report identifies the six major areas for Spanish action abroad as Europe; the Maghreb and all of Europe’s southern neighbourhood; Latin America; the US and the North Atlantic; Asia-Pacific; and the global sphere itself.

In all areas of European collective governance, and in particular the integration process, Spain has always been in the lead in cases of variable geometry. It is vital to continue to do so, as it actively helps to forestall dynamics that might lead to a break-up. In the debate on the EU’s future, Spain should continue to foster the construction of supranational institutions and strengthen its already especially close relations with the other big five member States and, among them, with those which also belong to the Euro Zone (Germany, France and Italy), without neglecting other possible medium-sized (particularly its neighbour Portugal) and smaller allies. Spain has its own view on enlargement, and it is advisable to maintain a European perspective regarding Turkey and the Western Balkans. It must pay greater attention to Russia and the eastern neighbourhood, acting in step with its Western partners.

Spain, as a natural bridge between North Africa and Europe, has a strategic interest in the Mediterranean becoming a geopolitical space of its own –with effective multilateral bodies– and in the EU strengthening its support to its southern neighbourhood at a time of difficult but encouraging transformations. Spain must deepen its good relations with Morocco and, at the same time, become involved in a balanced way in the attempt to improve relations between all the States in the Maghreb. The Middle East is also important for Spain but, considering its real priorities and the complexities of such a conflict-ridden area, it would be advisable for it to channel through the EU part of the political effort it has so far devoted to the region. In contrast, an area to which Spain should pay greater attention and for which it should draw up a comprehensive action plan is the extensive region around the Sahel, stretching from the Gulf of Guinea to the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa. Finally, and especially since the business links between Sub-Saharan Africa and Spain are rapidly growing, the expanded economic relationship should have an adequate response in the political field.

Latin America is central to achieving most of these strategic objectives. Spain’s special relationship with the region provides it with an extra degree of influence in all its other fields of external action. In parallel with Latin America’s efforts to establish its own multilateral governance, the Ibero-American Summits need to be rethought, preserving their ‘family diplomacy’ character, mainly aimed at promoting cooperation in all spheres on the sound basis of a close-knit and active network that unites the civil societies on both sides of the Atlantic. But Spain should also act bilaterally with every Latin American country with a distinct policy for each based on strategic criteria. Brazil’s increasing importance in the global and regional arenas, and the lesser attention that Spain has paid to it for historical reasons, calls for an extra effort in this bilateral relationship. With all the remaining Spanish-speaking countries (from Mexico to the smallest of them) it can undertake ambitious projects and other actions of substantial political value.

Spain’s integration into the Atlantic space is based fundamentally on NATO; thus, without undervaluing the latter, it would seem desirable for its future relations to have broader institutional foundations. The completion of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership that Spain fully supports could contribute decisively to this purpose, paying particular attention to its potential impact on Latin America. At the bilateral level, the US remains an essential ally but it would also be sensible to complement the close link between the two countries on security matters with more links in the economic, cultural and scientific spheres.

Despite the fact that the Asia-Pacific region is playing the leading role in the major transformation of economic power and global governance that is currently taking place, Spain cannot realistically put it high up on its list of priorities. Nevertheless, it should have a greater say in designing the EU’s Asian policy. On the other hand, Spain should have its own approach and an individualised relationship with several countries in the region, particularly China. To attract Asia’s attention, it would be advisable for Spain to step up its efforts in bolstering its image, which is not well established, and in promoting the Spanish language.

Finally, there is a specific arena for dealing with affairs of a global nature in which Spain, both through the EU and autonomously, ought to be present, prioritising the debates in which it has more interests at stake. The aim of its action in the global sphere is twofold: on the one hand, to contribute to the provision of public goods and, on the other, to establish legitimate and effective rules of governance. This is a key aspiration for a highly inter-dependent country, which is an EU member State and lacks the capacity to impose its interests by itself. Spain must act in this respect with an awareness of its weaknesses (struggling to gain a recognition in governance circles that is appropriate to its objective weight) but also of its comparative advantages (such as a significant capacity to manage diversified bilateral relations and a great potential for encouraging interregional and triangular dialogue).

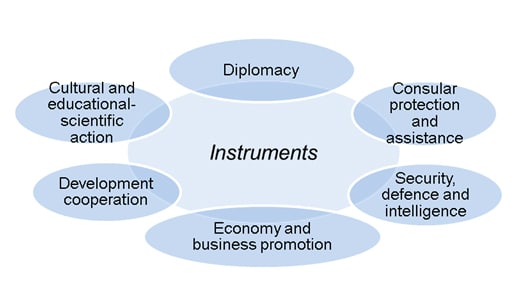

Developing a strategic foreign policy requires an intelligent combination of a number of instruments, to be used by the Spanish government’s various departments, but with a growing input from the EU, the autonomous communities and the private sector.

Among the six instruments identified in this Report, diplomacy plays a key role as it must distil a general political essence out of the combination of all sector-specific external actions. This overall picture must be considered when diplomacy represents, negotiates and, especially, reports back to its superiors so that the latter can better plan and supervise the implementation of policy. Consular assistance and protection is the second main instrument of external action. It is not only the visible point of contact between its practitioners and the public, which is increasingly alert to the quality and even the utility of the services it is provided, but it also contributes directly to improving Spanish society’s international projection. A greater effort must be made to give the consular service the importance it deserves by modernising it, especially by equipping it with adequate information technologies and rethinking its rather reactive approach to serving the public.

The third major instrument comprises security, defence and intelligence. The three contribute influence, presence and international cooperation to Spain’s external action. Kept apart in the past, both territorially and functionally, they now converge in the continuum between domestic and foreign policy, between national and global security, protecting external action in the new spheres and risks of a globalised world. The instrument for the external promotion of economic and business interests can make use of particularly diverse tools, which have increased in number in recent years, with new players from civil society and the sub-state administrations. Equally varied is the instrument for development cooperation, which operates through a complex network of public and private actors. Finally, cultural and educational-scientific action is an essential instrument that, on the one hand, contributes to enhancing Spain’s internationalisation and, on the other, helps to project its image and improve its influence through soft power.

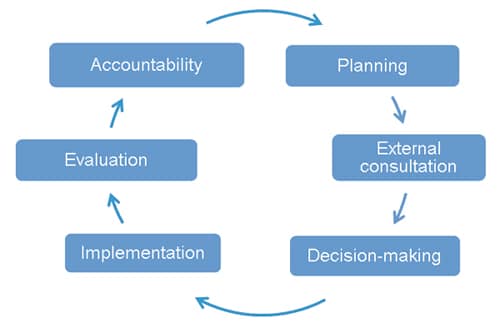

The Report concludes with a proposal for a new, comprehensive and integrated system to carry out a truly strategic external action. The same need for a cross-cutting perspective without watertight categories, as advocated above to identify objectives and understand the instruments available, also applies to the six phases that comprise the making of foreign policy: planning, external consultation, decision-making, implementation, evaluation and accountability.

Furthermore, while respecting the strategic foreign policy objectives that are ultimately determined by the Spanish government, it would be advisable to count on the engagement and cooperation of other players. Among the latter are the autonomous communities, which are responsible for many public policies with a potential for external projection as a result of the extensive decentralisation of competences that characterises the Spanish political system. The relationship between the external action of the central government and that of sub-state or private actors should not rest so much on new coordinating or hierarchical mechanisms, but rather on the generation of a feeling of reciprocal appropriation or, at least, a climate of understanding.

It is true that external action should ensure the internal coherence and synergy of highly diverse national players and interests that act in a complex international reality. But while agreeing with this premise, this Report suggests a new way of attempting to resolve this problem. Rather than coordination, which is connected in the Spanish administrative tradition to the idea of control or even subordination, priority should be given to integration, understood as a means of ensuring the direct participation of all actors in the process and facilitating convergence. Since this is essentially a method to seek to transform the prevailing administrative culture, which is overly departmentalised and legalistic, a move towards integration would hardly require any legal or organic changes, but rather just the strategic reorientation of operations.

The integration of external action should be based on three equally important organisational mechanisms: the Prime Minister, a collegiate political council and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation. The Prime Minister, who in Spain has the major responsibility for political direction, does not currently have a system to enable him to exercise effective strategic leadership over the country’s external action, either when collectively presiding over all the departments involved or in his personal field of action that, moreover, includes taking all major critical decisions. The function of the political council, which needs the appropriate but flexible and streamlined technical support, is to provide a political meeting place for those involved in Spain’s external action. For its part, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation must reformulate its geographical approach and, especially, reinforce its currently thematic approach. The idea is to have a proper overall view of each region and country and to act to as a major catalyst to help integrate all the policies that have an external projection. Abroad, integration can be implemented through a three-way mechanism that seeks to combine the hierarchical, collective and departmental components under the ambassador’s leadership.

Integration mechanisms should not be designed to be exhaustive but be limited to the priority objectives of foreign policy, especially at the stages of planning, external consultancy and evaluation. In contrast, in most of the decision-making and especially implementation processes, each actor should maintain his own sphere of action. The main tool for integration should be an External Action Strategy, a political document to be approved by the government on the basis of a draft by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, in whose drafting it should be essential for other actors to take part and which must be debated in parliament. The integration system should also be entrusted with the annual supervision of the Strategy’s implementation, ensuring that guidelines are followed, deviations corrected and crisis situations dealt with appropriately.

The final two elements of the integration system should be evaluation and accountability, which seek to value the functioning and results of external action as a public service. Evaluation monitors effectiveness, supervising the work carried out by the players involved, analysing the lessons learnt and reviewing strategies and future plans. Accountability has a political content since it connects the system to the public through their representatives in parliament. But parliamentary participation in external action should not only be concerned with control: it should to a great extent also ensure that there is adequate communication between the people and the authorities, laying the foundations for a consensus between government and opposition.

Finally, in terms of resources, the strategic renewal of Spain’s foreign policy should seek to bridge the gap between overly ambitious aims and scarcely adequate means. Regarding human resources, better use should be made of the scope to improve recruitment and training and to encourage mobility between the different agencies of external action. It would also be desirable to better connect promotion and the provision of jobs, whether in Spain or abroad, to the evaluation of individual performance and training. As for material means, it is important to note that the process of transforming external action as proposed in this Report should have its own budget and funds, the cost of which should be offset in the medium term by improvements in efficiency. In addition, and in general terms, attempts should be made to modernise and rationalise material resources, making diplomatic and consular redeployment much more flexible.

The Report’s conclusions

The Report closes with conclusions that are formulated as recommendations. Globalisation breaks down the barriers between the internal and the external, stressing the need to develop an integrated, coherent and stable external action. The recommendations, in the Elcano Royal Institute’s view, constitute the 10 foundations on which to base a renewed vision of Spain’s place in the world and of the realistic but influential role that it can play as a medium-sized power with a global presence, and as an advanced, responsible and pro-European democracy that seeks a collective model based on coexistence, security, sustainable prosperity, culture and knowledge.

- IN THE SERVICE OF THE PUBLIC. The strategic renewal of Spanish foreign policy must be guided by the promotion of the public’s values and interests. This task must be carried out both within the country’s borders –so that the public believe that external action brings them benefits in the fields of democracy, security, sustainable prosperity and knowledge– as well as beyond them, taking into account the growing international presence of Spaniards that require assistance and protection. Education, participation, proximity, transparency and a search for social support will form an essential part of future external action. This will also make decision-making more democratic, stable and efficiency-oriented.

- BETTER CONNECTING SPAIN TO THE WORLD. The priority aim of a strategic foreign policy is to better link the country with its new international environment, which is transforming the daily parameters of welfare and security. The connection must not only be limited to the public administrations, but also reach every personal, business or social project so that they can better face the challenges and opportunities of globalisation. This effort, channelled through better training and communication, should also lead to a change in collective mentality. One of the 15 most important countries in the world –measured from almost all parameters– cannot have public authorities, social actors and a public that fail to pay greater attention to what is happening in the global environment. In addition, this approach will also favour majority-based and sustainable policies, reducing the risk of short-termism or, ultimately, vulnerability.

- INTELLIGENT EUROPEANISM AS A BASIS. To regain its prosperity and maintain its security, Spain needs an internally cohesive and globally active EU. Therefore, the Europeanism of Spain, which is the fifth-largest member state of an EU of almost 30 members, cannot be solely receptive or resigned. As well as loyally fulfilling its obligations as part of the integration process, Spain must be constantly active in driving and shaping it so that the progress made is in accordance with the country’s values and interests.

- AMBITIOUS FOR ITS OWN PRESENCE AND INFLUENCE. Spain’s substantial and loyal participation in the EU does not mean that it has to give up thinking and acting for itself. This is especially true in areas where it makes sense for it to do so due to the lack of a developed European external action, because the goals to fulfil are its own (the projection of its businesses, ideas or global language) or where the added value of the opportunities and/or risks for its security are particularly strong (Latin America and North Africa). As well as in these spaces, Spain has the capacity and vocation to have a greater presence in the major powers, the emerging regions and the management of truly global affairs.

- CO-RESPONSIBILITY IN GENERATING GLOBAL PUBLIC GOODS. As a matter of principle and given its interests in an interconnected world, Spain must project its values in the world and support a multilateral law-based governance. Promoting international peace, human rights and freedoms, development or the fight against climate change is not only an expression of solidarity or –even less so– a generous luxury, but rather an obligation to which it is duty-bound and which also contributes to improving democracy, security, prosperity and knowledge back home.

- BASED ON INNOVATION AND TALENT. Spain can only address globalisation through knowledge and added value. Protectionism, indebtedness and reducing welfare are not viable or acceptable options for a well-educated society in an open and interdependent world. This requires rethinking the country’s growth model, basing it on improvements in productivity that will come from a more internationalised education, talent attraction, a scientific system better connected to industry, and competitive businesses integrated into global value chains.

- PROJECTING A SOUND AND RESPECTED IMAGE. Spain must present itself as an active international actor with well-defined priorities, one that is capable of generating useful initiatives and that bases its credibility on the legitimacy of its political system and the robustness of its economy, which requires current weaknesses in those spheres to be addressed. Spain today is a tolerant, modern, sound, supportive, creative, plural and dependable country with a high quality of life, which respects the environment and values its historical legacy. This is the image that Spain can and must strive to project for it will help to improve the country’s self-confidence and external perceptions of Spanish ideas and products.

- THROUGH AN INTEGRATED SYSTEM OF INSTRUMENTS AND PLAYERS. Attempts to coordinate the foreign policy of a highly globalised society will struggle to succeed if important public and private actors do not feel included in designing the appropriate strategies. This creates the need for a collective system, one led at the highest level, mediated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation and with a strong parliamentary involvement. It must be less concerned with controlling than with integrating visions and instruments (diplomatic, consular, security, trade, cultural-scientific and cooperation) in an inclusive approach to the general interest.

- EQUIPPED WITH GREATER INTELLIGENCE. Spanish foreign policy is lacking in expert knowledge and the generation of ideas. It must reinforce its own thinking (both through planning units within the public authorities as well as relying on consultancy services from independent experts) from the phase of governmental planning through to parliamentary accountability. And this must be done not only in the short and medium terms but also by paying attention to the long-term outlook so that threats do not knock the country off course and it does not overlook opportunities.

- TAKING EVALUATION SERIOUSLY. Both the implementation of external action and the results obtained must be followed and measured systematically. Success or failure in attaining objectives must serve as a learning experience and prove decisive in maintaining or changing the course of action and the human and material resources employed.

Ignacio Molina

Coordinator of the Report’s editorial team, Elcano Royal Institute.