Theme

France, Germany and the Netherlands have issued strategic papers on the Indo-Pacific that could serve as an inspiration for other EU member states and for the development of a common EU strategy towards the region.

Summary

The Indo-Pacific guidelines issued by France, Germany and the Netherlands reflect their adaptation to global economic and power shifts that have made the region crucial for European economic and security interests, for the global balance of power and for the multilateral agenda. Faced with the uncertain maintenance of a benign regional hegemony and the challenges posed by China’s increasing influence and assertiveness , their guidelines offer a blueprint for an autonomous European approach, with the core objective to preserve an inclusive, rules-based and multilateral Indo-Pacific order.

To this end, the three countries have adopted comprehensive approaches, covering economic, political, military and technological cooperation, aimed at the diversification of regional relations through a network of economic and security partnerships with like-minded countries. Success remains uncertain, given the region’s economic dependence on China –which might jeopardise the autonomy of Europe’s Indo-Pacific partners– and the EU countries’ precarious political and financial commitment, especially in the post-COVID-19 period . In any case, these three strategies offer realistic and pragmatic orientations given Europe’s limited strategic presence in the region.

Analysis

There is a debate within the EU about the convenience of developing a common stance on the Indo-Pacific due to the increasing economic and geostrategic relevance of that region. France, Germany and the Netherlands have already issued their own guidelines, which could offer valuable inspiration for the EU and other member states. In contrast with the over-militarised US approach, these three countries have adopted comprehensive visions aimed at defending multilateralism through political, economic and security cooperation. Despite different interests, they present a similar strategic thinking, with an emphasis on multipolarity and diversification through a network of economic and security partnerships intended to preserve their strategic autonomy and that of the Indo-Pacific countries. This constitutes a solid ground for a unified and pragmatic EU strategy framed to respond as fully as possible to the main regional challenges of the next decades. On the other hand, crucial limitations remain, which will have to be addressed to achieve the expected strategic objectives.

(1) Diving into the Indo-Pacific: keeping up with global power shifts

The German and Dutch guidelines, as well as the two French strategies, are firstly driven by the geoeconomic and geopolitical shift from the Atlantic to the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The Indo-Pacific has become the main driver of global growth, and its increasing economic size, population and urban middle-class, give it a central role in globalisation. As conceptualised by the French authorities, the term covers an area of ‘geostrategic coherence [and] strategic continuity’ running from Eastern Africa and the Middle East to the South and Western Pacific. In comparison to the term Asia-Pacific, the Indo-Pacific incorporates the importance of India and the Indian Ocean, the centrality of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and that of the major sea lines of communication that link Europe to East Asia, and carry a major share of international trade and oil shipping.

The three countries acknowledge that global interdependence, and the shrinking of geopolitical space, make the Indo-Pacific an important area for the prosperity and security of the EU and EU member states. The region is key for the EU’s economic interests, as an export, innovation and necessary data market to remain competitive in the fourth industrial revolution. The Indo-Pacific will also be an essential actor in achieving the global green and climate transition, and its increasing role in the definition of international norms makes it a key actor for the future of multilateralism, the preservation of a rules-based order and the promotion of human rights. But it is also a space facing major challenges such as territorial disputes, nuclear proliferation, human security threats and severe US-China strategic rivalry, which favour power relations while eroding prevailing international norms. All these factors push EU stakeholders to strategically position themselves in the region.

France, Germany and the Netherlands share similar strategic interests, namely the defence of multilateralism and ‘freedom of trade and access to the common spaces that are essential to [their] security and prosperity’. To do so, they all endorse a strategic approach of which France offers the most obvious case, due to its sovereign interests in the region –overseas territories, economic exclusive zones, nationals and expatriates, and permanent military forces–. Indeed, both the French Armed Forces Ministry and the French Foreign Affairs Ministry released in 2019 their own Indo-Pacific strategies: France defence strategy in the Indo-Pacific and the French Strategy in the Indo-Pacific: ‘For an inclusive Indo-Pacific Space.1 The Dutch non-paper on the Indo-Pacific (Guidelines for strengthening Dutch and EU cooperation with partners in Asia) also champions a strategic approach ‘beyond trade and investment’,2 while the German Policy guidelines for the Indo-Pacific region include military and traditional security elements, power considerations and an overall strategic caution taking into account the ‘strategic quality of relations with countries of the region’ as well as possible ‘technical, security policy, economic, and social risks’.

The three countries call for an increased engagement in security in the Indo-Pacific, but this is only one component of a broad and comprehensive approach covering multilateral, military, economic and diplomatic cooperation. They also support devising an autonomous EU strategy for the Indo-Pacific. In fact, Germany’s guidelines have been explicitly developed with this aim, and the Dutch guidelines mainly revolve around an EU-level strategy (and how the Netherlands can contribute to it). The French strategies place less emphasis on the EU, but they also promote the ‘development of joint [EU] positions of the Indo-Pacific’ and the ‘strategic positioning of the EU in the region’. The three countries share the assessment that the EU level offers a better leverage to defend their national interest and gain more influence in the regional scene. Hence, their documents are likely to contribute to the development of a common EU stance on the Indo-Pacific.

(2) A shared objective: preserving an inclusive, rules-based and multilateral Indo-Pacific

Despite significant changes in the balance of power inside the region, the Indo-Pacific space has proved quite stable since the end of the Cold War. Territorial disputes and divisions have not led to large-scale military conflict while regional economic cooperation has registered exceptional growth. This has provided EU actors with many business opportunities without the need to make meaningful investments in regional security. In this context, the US has been perceived as a benign hegemon by the EU and its Indo-Pacific allies: as a provider of security and global common goods, and the guardian of a framework enabling economic cooperation. This appears in the French defence strategy which reminds that the US is a ‘crucial partner’ and ‘historical ally’ in the Indo-Pacific, and supports US multilateral initiatives in the region, including the Global Maritime Partnership Initiative and US efforts to achieve trilateral arms control agreements with China and Russia. This also explains their underlying preference for the existing balance of power and status quo –with the US as the main regional security provider–.

The scenario has been altered by the rise of China, which has generated a security dilemma for several Indo-Pacific countries and for the US. The EU is worried about eventual Chinese regional hegemony, since the normative breach between EU and Chinese stakeholders prevents the former from regarding China as a benign hegemon. Hence the three strategies reflect concern about the risk of the creation of a Chinese sphere of influence on its periphery, as growing power asymmetries and economic dependence between China and some Indo-Pacific countries could translate into political and strategic dependence from Beijing. They suggest, or explicitly mention, the lack of bilateral economic reciprocity and a level-playing field, the unsustainability of Chinese infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, which are also regarded as cases of unfair competition in third markets), China’s human rights governance shortfalls (which could have implications on human rights governance in the region) and its destabilising role in the security and maritime domains.

The most vocal of these European official documents is the French defence strategy, which denounces that ‘China’s close relation with Russia in challenging democratic values, its enduring support to North Korea, its strategic partnership with Pakistan, the ongoing borders issues with India as well as the territorial disputes in the East and South China seas generate deep-seated concerns regarding the implications of China’s actions’. It also points out that the development of China’s military capabilities seeks to redefine the regional balance of power. The Dutch and German guidelines are less explicit, but they also point to China’s destabilising actions and violations of UNCLOS in the South China Sea. The Dutch guidelines also emphasise China’s ‘hybrid manner of pursuing strategic goals’ through a centralised system of economic, political, military, cyber, security and intelligence activities.

Although the Biden Administration provides renewed opportunities for transatlantic cooperation in many areas, including the Indo-Pacific, the presidency of Donald Trump evinced in the eyes of many European leaders the risks of overdependence on the US and the negative implications that the US’s China policy could have on international economic and security cooperation. The EU’s reaction and the central goal of the Indo-Pacific strategies issued by three of its member states is to bet on a multilateral order. The order would be open (facilitating international cooperation), inclusive (welcoming all actors) and rules-based (where respect of rules is the entry criteria). Such a multilateral order is expected to ensure stability, predictability and satisfactory outcomes for all participants, regardless of their power capabilities. In that respect, their strategic vision of an open, inclusive and rules-based multilateral Indo-Pacific is closer to that of local actors, namely Japan, South Korea and ASEAN, which would like to keep substantial economic relations with China and the US engaged with regional security.

Multilateralism is both an objective and a mean for EU stakeholders in the Indo-Pacific. Hence, France, Germany and the Netherlands have underlined an enhanced engagement in existing and emerging multilateral institutions, in particular with ASEAN, which has been systematically presented as a privileged partner and became a strategic partner of the EU on 1 December 2020. This predilection for multipolarity includes the security dimension thanks to inclusive mechanisms that offer opportunities for fostering trust-building and peaceful conflict resolution. These EU countries also promote the institutional framework of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to achieve ‘peaceful, rules-based and cooperative solutions’, although Germany appears less forthright than France and the Netherlands in that respect.

Their promotion of an open, multilateral and rules-based regional order also translates into normative approaches to connectivity (based on sustainability, shared norms, values and a level global playing field) and (human-centred) technology, which is a key topic for many countries in the region. The EU countries also promote the improvement of human rights, whose protection in several Indo-Pacific countries remains insufficient. Although they favour ‘open [and] critical’ dialogues on this issue, they also endorse firm stances. For example, the German guidelines assert that human rights are a necessary condition for (regional) peace, security and stability, and that they are universal, indivisible and complementary to economic development (at odds with the relativistic conceptions of human rights held by some governments in the region).

(3) A broad and multisector approach to regional issues and security challenges

The three strategies present a holistic approach towards the Indo-Pacific, encompassing a broad range of sectors, trade and investment, connectivity (including digital connectivity), traditional and non-traditional security, human rights, and scientific and cultural cooperation, and the interconnections between them. As stated in the French Indo-Pacific strategy, they also aim to support the full spectrum of ongoing regional economic, demographic, territorial, energy and technological transitions. This approach helps the EU and its member states to leverage their greatest strengths in the region, which do not lie in the field of hard security.

They also share a comprehensive assessment of security threats. The European strategies foster human security and non-traditional risk awareness, covering poverty and development, disaster relief, terrorism, pandemics and a particular emphasis on climate change that is recognised as a risk multiplier. The 2018 French defence strategy goes further, as it considers climate events as ‘military events’ whose impact on territories, populations and state resilience generates ‘new security breaches [and] new conflicts’. The three countries also converge on assessing that new technologies offer cooperation opportunities but also entail security risks. This is the case of dual-use technologies, including artificial intelligence, cyber and space technology, and those that sustain military access denial and projection capabilities.

Maritime security, which intersects both non-traditional and traditional security, is consistently highlighted as a central security concern by European Indo-Pacific strategies. As stated in the 2019 French defence strategy, maritime security covers ‘counter piracy, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, maritime terrorism, and any kind of trafficking’. But it is also related to freedom of navigation and overflight and the challenges some states pose to the principles of UNCLOS. The maritime domain appears as a space of inter-state tensions, in the same way as the Korean peninsula and other border disagreements. It is also related with the development and modernisation of maritime military capabilities, including coastal defence capabilities and blue water naval assets, which contribute to the hardening of an ‘unfavourable [maritime] military operational environment’. The three countries also pay a particular attention to nuclear security. North Korea’s proliferation appears as the major and most immediate concern, but the unique, rapid and opaque development and extensive modernisation of China’s nuclear capabilities also fosters long-term concerns. Finally, the European strategies mention hybrid threats and ‘grey zone activities’, including movement of troops in border areas, ballistic missile tests and repeated incidents in the commons. Along those lines, they also take into consideration the disruptive impact of disinformation and influence operations by ‘authoritarian actors’, which poses a risk to the legitimacy of democratic regimes.

(4) A multipolar alternative: diversification through cooperation with like-minded countries

The emphasis on multilateralism by EU actors does not mean that their strategies do not favour a specific balance-of-power structure. There is a preference for a multipolar Asia ‘where no country imposes hegemony’ by developing alternatives (for the EU and) for Indo-Pacific middle powers to preserve their sovereign freedom of choice. This inclination towards multipolarity is particularly apparent in the French and Dutch strategies, though the establishment of a network of economic and security partnerships with regional like-minded partners, ‘democratic’, ‘with market economies… committed to effective multilateralism’, which share a ‘community of values and interests’. Namely, this includes Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, India and most ASEAN countries –Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam–. Among them, Japan, South Korea and India appear as privileged partners when it comes to new technologies, be it 5G (security) or artificial intelligence and in the development of standards and ‘international framework conditions for industry 4.0’. This indiscriminate and normative categorisation, combining multilateralism, democracy and market economy, is quite problematic. EU countries do indeed share political and economic liberal values and systems with Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea. This is highlighted in the bilateral EU-Japan and EU-ROK strategic partnerships. But this proximity is uncertain at best with other Indo-Pacific partners. South and South-East Asian countries do not have such a good record on human rights and democracy, and there are additional concerns that COVID-19 may strengthen existing authoritarian tendencies. But they also rank low in open-economy indexes, eg on foreign direct investment (FDI) restrictiveness.

Nevertheless, the preference for multipolarity suggests a kind of external balancing against hegemonic or bipolar configurations. The guiding principle here is diversification as a way to benefit from ‘all [potential economic] opportunities’ but mainly to avoid ‘one-side strategic dependencies’. Although this strategic imperative applies to both EU and Indo-Pacific countries, concerns primarily relate to the latter. The French strategy explicitly aims to strengthen the strategic autonomy of France’s South-East Asian partners, while the Dutch guidelines emphasise that Indo-Pacific countries need ‘geopolitical and other strategic support from the EU’ that should provide ‘a counterweight to the strategic economic and military influence of one or more great powers’. In contrast, the EU countries’ strategic dependence on China remains rather limited and rather applies to the US and the possibility of following autonomous and inclusive strategies in the region. A recent study by MERICS points out that the EU’s trade dependence on China is limited and mainly involves (non-strategic) consumer goods. It is more acute in digital technologies and electronic components, but dependence goes both ways, as EU sectors such as chemicals and several niche manufacturing sectors are also crucial to China. However, the EU’s strategic dependence may increase as regards the supply of critical raw materials for green technologies, mainly rare earths, while China’s redoubled efforts and dual-circulation strategy to achieve greater autonomy may affect this bargaining balance.

On the economic side, the three strategies promote the conclusion of ‘modern [inclusive and sustainable] trade and investment protection agreements’, covering issues like ‘climate, competition policy, SOEs, subsidies, social standards and human rights’.Emphasis is put on ASEAN, at the bilateral and regional level, with the promotion of strategic partnerships and free trade agreements (FTA) with its member states, and with the organisation as a whole. The European strategies also mention Australia, New Zealand, and India, the latter being likely more inclined for greater economic cooperation now that it has stayed out of the recently concluded Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and faces growth challenges worsened by COVID-19. Beyond trade and investment, they also promote increased cooperation in new technologies and industry 4.0. This also applies to (infrastructure) connectivity, with a particular emphasis on sustainability (in contrast with the BRI), through the implementation of the EU connectivity strategy and the replication of the EU-Japan Partnership on Sustainable Connectivity and Quality Infrastructure with other partners, mainly ASEAN and India.The connection between connectivity and strategic autonomy are apparent in the European Indo-Pacific strategies. Germany presents the EU connectivity strategy as a tool to preserve the Indo-Pacific countries’ ‘economic and political sovereignty’, while the Dutch guidelines emphasise that the development of new digital technologies is linked to ‘national (digital) sovereignty’ and that unilateral technological or economic dependence must be prevented.

On the other side, the three countries aim to strengthen their network of security cooperation with like-minded partners, with a focus on maritime security, to contribute to regional peace and stability. This results from a multipolar approach and is an apparent necessity given the limited military capabilities of the European powers in the Indo-Pacific. The three countries outline the need to build-up their strategic presence in the region. The German guidelines point out that the ‘use without hindrance of maritime transport and supply routes requires investment in, and maintenance of military capabilities’, and Germany has recently committed to deploy of frigate in the region in 2021, a significant decision coming from a pacifist nation whose military is constitutionally defined as purely defensive. The French defence strategy talks about ‘preserv[ing] and reinvest[ing] in [France’s] prepositioned forces, which allow[s it] to operate with strategic depth, far from Europe, in addition to regular deployments of air and naval assets’.Even France’s permanent military assets appear rather limited (in addition to being far from the Indo-Pacific’s main conflict hotspots) given the quantitative and qualitative development of regional navies and anti-access/area denial capabilities. For instance, the 2018 French defence strategy only registered four surveillance frigates, and two multi-mission ships, split between the military bases of New Caledonia, French Polynesia, la Réunion and Mayotte. Therefore, the three countries mainly adopt an indirect approach, through security partnerships, arm exports agreements and capacity-building activities. The Dutch and German guidelines push for an increase of security cooperation through the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and the deepening of the latter’s partnerships with Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea. Beyond that, the three countries seek to reinforce their partnerships with ASEAN countries, including Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam, with whom they share ‘similar assessments of the situation in the Indo-Pacific’, a ‘common analysis of main [strategic] challenges’ and ‘[convergent] views on key regional issues’. This indirect approach also relies on arms exports, in compliance with arms control agreements, to strengthen and support the modernisation of allies and partners’ capabilities, as well as on capacity-building, especially in maritime security, surveillance capabilities and enforcement of the UNCLOS principles.

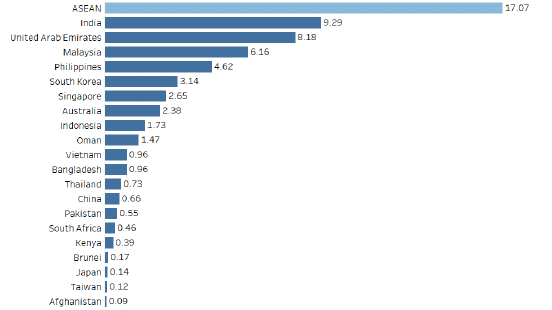

Despite the low visibility of these strategies –compared with ASEAN–, Japan, South Korea and India will clearly be key and core partners of this network architecture. The first two countries offer advanced instruments for bilateral cooperation through the comprehensive EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), the Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA) and the EU-Republic of Korea strategic partnership. They also offer significant potential for cooperation in third countries, in ASEAN and beyond, and possess the required financial, material and human resources to achieve these cooperation objectives and ensure balanced commitments. At the same time, the three countries seek to deepen their relations and partnerships with India, with the signing of a ‘comprehensive and ambitious’ free-trade agreement or through bilateral and multilateral cooperation on connectivity, climate change and renewable energies, with the specific mention of the International Solar Alliance launched in 2015. India will also prove a crucial partner for security. French defence strategy already points to a ‘privileged defence relationship guaranteeing the strategic autonomy of both countries’. India is also a pilot country under the EU’s ‘Security cooperation in and with Asia’ initiative on maritime security, counter-terrorism, UN peace-keeping and cybersecurity, and, most importantly, it is the EU’s top arms export partner in the region, second only to ASEAN as a whole (see Figure 1).

(5) An uncertain reach: middle-sized powers with significant limitations

Although the networking approach of France, Germany and the Netherlands matches their capabilities and actual presence in the region, they face some crucial limitations that might jeopardise the objective of a rules-based multilateral Indo-Pacific.

On the economic side it remains unclear to what extent the European strategies can achieve diversification, since genuine diversification would not only require increased economic ties between EU and the Indo-Pacific countries but also a relative decrease of the Indo-Pacific countries’ dependence on China in terms of both trade and investment. China is already deeply incorporated within ASEAN’s regional value chains and COVID-19 has helped it to become ASEAN’s top export and import market in the first half of 2020. Taking into account the economic growth forecasts for the EU and China, the latter will likely replace the EU as ASEAN’s main trading partner on a permanent basis. China’s technological engagement in ASEAN is also increasing in the 4.0 industry digital ecosystem, cloud markets and smart cities. In addition, China was the fourth-largest source of FDI in the sub-region in 2019 and has emerged as the second-biggest bilateral international source of infrastructure financing behind Japan.

This should have crucial implications for ASEAN’s centrality, its role as multilateral guarantor and its capacity to preserve its strategic autonomy. ASEAN’s enlargement in the aftermath of the Cold War has diluted its shared geostrategic interests and made more complex its consensus-based decision mechanisms. Adding to varying level of threat perception towards Beijing, this has provided China with strategic openings and partners like Cambodia, prone to accommodate Beijing’s interests while affecting ASEAN’s unity. This could endanger ASEAN’s role in the South China Sea and the Indo-Pacific in general.

In addition, most EU countries still fail to see the Indo-Pacific as a high-priority strategic area and therefore it is still uncertain whether they will show the necessary political will to sustain significant commitments towards the region. This could be further aggravated in the current context when the European authorities and public opinion are focuded on domestic issues and recovery. The most obvious exception is France, at least as long as its overseas assets are concerned. But even France’s strategies would require increased financial resources to achieve their objectives. This, adding to Europe’s limited military capabilities, may jeopardise the credibility of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy and confine European countries to being perceived as actors strategically subordinated to the US, lowering the interest that Indo-Pacific countries might have to directly engage with them.

So far, France’s status of ‘island state’ has provided it with the necessary credibility to become a major strategic partner for Australia, India and Japan but, overall, traditional security will remain an area where the EU and its member states will likely struggle to gain a meaningful role. Non-traditional security should provide more opportunities to do so, but issues like nuclear security or the conduct of freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea should prove to be more challenging. Apart from isolated maritime deployments, the European military presence in the Western pacific will remain limited, especially due to geographical constraints. But this may not necessarily be such a weakness, as the very concept of the Indo-Pacific highlights that there are more strategic areas than East Asia. As detailed in the French defence strategy, France’s most institutionalised security partnerships are to be found in the Persian Gulf –the Indo-Pacific North-West–. This area remains crucial in the geopolitics of energy and, as such, would remain a privileged –and closer– area for the EU to contribute to the overall Indo-Pacific balance of power.

Conclusions

The way forward

Although the actual impact of the strategic papers drafted by France, Germany and the Netherlands on the Indo-Pacific depends on many factors, including the level of commitment by their governments, they provide fertile ground for developing a coherent EU approach towards the Indo-Pacific. They also offer inspiration to other EU member states that, considering their own interests and priorities, would like to develop a strategic approach towards the region. The three strategies concur that the Indo-Pacific has become crucial for their economic prosperity and security, and that current geopolitical dynamics, namely the rise of a systemic rival, and US-Chinese competition, call for the EU and EU member states to step in. Their comprehensive strategies are framed to favour an open, inclusive and rules-based multilateral Indo-Pacific order through a network of economic and security agreements with like-minded partners, favouring tangible cooperation in key areas of mutual interest such as climate change, digital economy, connectivity and maritime security.

Nevertheless, it would be beneficial for an eventual EU strategy towards the Indo-Pacific to have a clearer normative hierarchy. This would require a debate on whether to emphasise the defence of a rules-based multilateral order over other normative elements that, although desirable, generate less enthusiasm among some of the regional leaders. Neither the ASEAN’s outlook on the Indo-Pacific, Japan nor South Korea incorporate democracy and human rights as core principles of their foreign policy in the region. Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific fundamental principles are limited to free trade, freedom of navigation and the rule of law, and its approach to ASEAN promotes a rules-based Indo-Pacific region while encouraging ASEAN’s principles of transparency and good governance. Similarly, South Korea’s new southern policy is restricted to cultural and economic cooperation, in addition to the promotion of a ‘peaceful and safe [regional] environment’. This is not to say that democracy and human rights should not be promoted and any setback condemned, but endorsing them as core strategic and policy principles when engaging with the region may prove counterproductive for forging the broadest possible middle-sized-power coalition to efficiently reset hegemonic dynamics, receive a lukewarm response from regional actors and expose Europe’s limited influence on this issue, which may ultimately harm its credibility.

Mario Esteban

Senior Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute and Professor at the Autonomous University of Madrid | @wizma9

Ugo Armanini

Research Assistant at the Elcano Royal Institute

1 Respectively mentioned in this paper as the ‘French defence strategy’ and the ‘French Indo-Pacific strategy’. A first French defence strategy was released in 2018.

2 As the Dutch non-paper on the Indo-Pacific has not been translated in English, quotes of the document refer to a non-official translation provided by the Clingendael Institute.

3Asian and MENA countries included in the French Indo-Pacific strategy.

4 The amounts correspond to the total value of export licences.