Theme

Despite its shortcomings, the international liberal order is worth saving. Therefore, international actors committed to that system, such as the EU and Japan, should cooperate in its revitalisation.

Summary

The rise of emerging powers and a significant questioning of key pillars of the liberal order in some OECD countries bring uncertainty to the durability of the current international order. Despite its shortcomings, this open and rule-based international liberal order has created conditions for reaching unprecedented levels of socioeconomic development and stability across the world. Therefore, likeminded actors such as Europe and Japan should redouble their efforts to reinvest the features of the liberal order that favour inclusiveness and fairness. Doing so, they will make it less likely for rising powers to resort to force to secure their interests and will deal more effectively with daunting traditional security threats and the provision of global common goods. The adoption of an EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and a Strategic Partnership Agreement would be the clearest signal that Brussels and Tokyo are joining forces in this task.

Analysis

Although the international liberal order has favoured freedom, prosperity and stability across the globe more than any past international order, its own excesses and the growing international influence of countries that did not participate in its creation are putting its durability at risk.1

In this context, where the validity of the international liberal order is under question both in the OECD countries and beyond, Europe and Japan should redouble their efforts to reinvest the features of the liberal order that promote inclusiveness and fairness abroad and at home. Doing so, they will make less it likely for rising powers to resort to force to secure their interests and will mobilise domestic support for its preservation. Moreover, the joint reinforcement and improvement of the liberal order is the more effective strategy for facing both daunting traditional security threats, like the North Korean nuclear crisis, and the provision of global common goods as epitomised by the UN’s Sustainable-Development Goals.

The EU and Japan have traditionally been two of the main supporters of the liberal international order in close cooperation with the US and its allies. As advanced, industrialised democracies, the EU and Japan have many common interests and work together regularly with one another in many international and multilateral forums. Over the years the scope of the EU-Japan relationship has broadened from the trade-related issues of the 1970s and 80s and the intensity of their cooperation has deepened to the extent that at the EU-Japan Summit of July 2017 a political agreement was announced to conclude a bilateral Economic Partnership Agreement and a Strategic Partnership Agreement based on shared fundamental values. The actual adoption of these agreements would be the clearest signal that Brussels and Tokyo are joining forces in the revitalisation of the liberal order.

The questioning of an international order that is worth saving

According to John Ikenberry, the international liberal order reflects the merger (or overlap) of two very different projects. On the one hand, there is the modern system of States that dates back to the Peace of Westphalia (1648), based on their inviolable sovereignty; on the other, a political and economic order that essentially emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries promoted by the US and the UK in opposition to authoritarianism and mercantilism. This dichotomy resulted in a certain contradiction between the State-centred Westphalian system and the global economic governance institutions created after the Second World War.

These tensions became aggravated in the aftermath of the Cold War, when certain OECD countries wanted to add institutional and conceptual elements to the liberal order, such as the International Criminal Court and the Responsibility to Protect, which eroded the Westphalian principle of national sovereignty in the name of Human Rights. These developments facilitated US-led interventions with very questionable results in countries such as Iraq and Libya. In view of these events, a significant number of countries, many of them with a history of colonial oppression, and some of them with impeccable democratic credentials, voiced their opposition to the erosion of the principle of State sovereignty, which they regarded as a means of defence against the hegemon. This popular narrative in non-OECD countries clashes with a prevalent narrative in OECD countries that underlines the beneficial nature of US hegemony thanks to its leading role in the provision of global common goods such as security, free trade and financial stability.

Whereas the political interventionist nature of the liberal order is mainly questioned in non-OECD countries, the economic foundations of the liberal order are receiving growing criticism in OECD countries as a raising protectionism and inward-looking trends seem to indicate. The acceleration of globalisation experienced after the end of the Cold War has pushed forwards a swift liberalisation of the global economic order, particularly after the creation of the World Trade Organisation in 1994. This is perhaps the most inclusive area of the current international order, since it has allowed the full participation of States such as the People’s Republic of China (2001) and the Russian Federation (2012), which did not participate in its creation.

One of the most significant results of the integration of the developing economies in the liberal economic order has been a massive growth of the middle classes in those countries, with a consequent increase in social support for that international economic order. On the contrary, growing inequalities and the deterioration, whether in absolute or relative terms, of the standards of living of the middle classes in the most developed economies have fostered opposition to the liberal international economic order in the shape of nationalist populism and anti-globalisation movements. Brexit and the election of Donald Trump are the two most visible examples of the phenomenon. Political criticism of the liberal order from non-OECD countries and economic criticism from OECD countries are sometimes connected, in particular through Russian hybrid practices such as information warfare and fake news.

Despite all its shortcomings, the international liberal order should not be discarded, but reformed. Going back to Ikenberry, the liberal international order has brought unprecedented levels of peace and prosperity to mankind thanks to two of its features: it is inclusive and it is based on rules. The liberal international economic order is built upon rules of nondiscrimination and market openness, establishing a system with low participation barriers, high potential returns and a broad distribution of economic benefits beyond the leading powers. The rise of China and its claim to be a champion of free trade and globalisation in the context of the protectionist Trump Administration illustrate the high standards of inclusiveness of the liberal order. Along the same lines, the dense network of multilateral norms and institutions that structures the international liberal order restricts power politics and makes the behaviour of international actors more predictable. By doing so, the international liberal order facilitates cooperation and collective problem solving, which is essential for tackling many challenges such as climate change, international terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, whose effective solution is well beyond the capabilities of a single State.

What can Europe and Japan do?

In order to reinvigorate the international liberal order, Europe and Japan should increase their commitment to its normative and institutional foundations, being more willing to bind themselves to international law and institutions, and should try to persuade their traditional allies to do so. The EU and Japan should cooperate to lead different multilateral agreements and institutions in multiple areas such as free trade, global warming, nuclear proliferation and terrorism. Their leadership should be exercised in an open, inclusive and rule-based manner that spreads gains widely, both within and outside their borders, instead of adopting a narrow focus on maintaining the current balance of power. This is not to deny that some global and regional balances of power could be more conductive than others to the preservation of the international liberal order. But by following this course, with a greater concern about absolute than relative gains, Europe and Japan are more likely to continue to be a source of international prosperity and stability than of geopolitical or economic disruption.

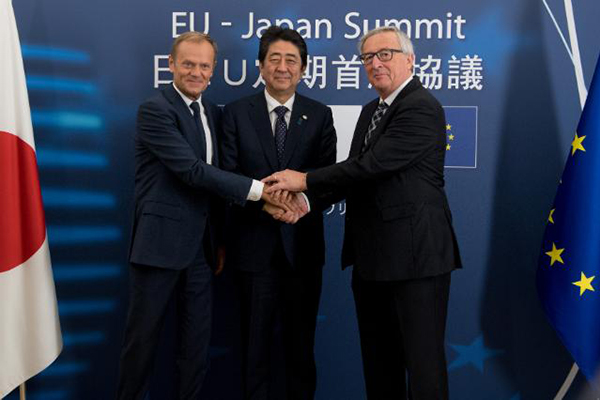

Besides cooperating along these lines both at the multilateral and bilateral levels, the strongest signal that the EU, its member States and Japan could send to the international community would establishing bilateral economic and strategic partnership agreements. The negotiations for a EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement started in 2013, but at that time none of the actors involved took them as a priority. However, the process accelerated in 2017. On 6 July, Donald Tusk, Jean-Claude Juncker and Shinzō Abe announced an agreement in principle on the main elements of the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and the negotiations were finalised on 8 December. If drawing up, translating and approving the Partnership Agreement by the European and concerned national parliaments go smoothly, the bilateral free-trade agreement could come into force in 2019.

The Economic Partnership Agreement should bring substantial economic gains to both sides, the EU estimates it will save €1 billion in customs duties per year and boost annual exports to Japan from €80 billion to more than €100 billion, while Japan expects a similar saving in customs duties and a 29% increase in exports to the EU. However, the speeding up of negotiations has had other motives. The completion of such an ambitious free-trade agreement –covering a wide range of issues such as trade in goods and services, intellectual property rights, non-tariff measures, public procurement and investments, by two of the biggest economies of the world, which jointly comprise 19% of world GDP and 38% of global exports– would have two significant implications. First, it will help the EU and Japan shape global trade rules in line with their high standards and regulations. Secondly, it will be a clear message against protectionism, showing that two of the biggest global economies are willing to further liberalise even if the US is taking a protectionist turn.

Both sides should also take advantage of the momentum created by the progress made in the economic partnership agreement to strengthen bilateral cooperation in dealing with common socioeconomic challenges, such as growing inequality and the sustainability of the welfare state, which are contributing to raising domestic discontent against the liberal order. Both sides have valuable experience in dealing with this and related issues, such as the technological revolution, ageing population and educational reform, and should increase their exchange of good practices in these fields through regular sectoral dialogues. In addition, other related issues, such as tax avoidance and evasion, cannot be fought only at the national level but should be tackled at international forums, like the G20 framework, where the EU and Japan cooperate.

In parallel to the Economic Partnership Agreement, the EU and Japan negotiated a Strategic Partnership Agreement since they decided that both would be adopted simultaneously. As mentioned above regarding the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement, the Strategic Partnership Agreement is also regarded in Brussels and Tokyo as a sign of their commitment to upholding and reinforcing the normative foundations of the liberal order. The Strategic Partnership Agreement would be a legally binding pact beyond political dialogue and policy cooperation, covering security policy and cooperation on regional and global challenges, such as climate change, development policy and disaster relief. In addition, the EU and Japan are currently negotiating a Framework Participation Agreement that would pave the way for Tokyo’s direct involvement in the operations and missions of the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy.

The adoption of the Strategic Partnership Agreement will be facilitated by the numerous similarities in the EU’s and Japan’s geostrategic perspectives on the world. Both are interested in preserving an open and stable maritime system globally, upon which their economic prosperity and security depend, and of the non-proliferation regime. In addition, both are aware that preserving a balance of power globally and in their respective home regions is critical to achieving these goals and they therefore oppose unilateral modifications of the status quo in contested areas. Moreover, both Europeans and Japanese are aware that they must contribute to preserving stability in other key regions, in particular the Persian Gulf and South and Central Asia, but also East Asia (in the case of Europeans) and Europe (in the case of Japan). This leads to another key common strategic objective, namely the preservation of the freedom of navigation in waterways that are key to communications within the Eurasian landmass, essentially the Indian Ocean but also, increasingly, the Arctic.

This shows that Europeans and Japanese share a great deal, because these geopolitical objectives guide their respective foreign and defence policies. Of course, they differ when it comes to prioritising, in the sense that they each give more attention to their immediate vicinities and the further away they get from them the less resources and political support there is available for supporting their objectives and vision. As such, the ‘meeting places’, and perhaps the best venues, for security cooperation between Japan and Europe are the so-called ‘middle spaces’ of the Indian Ocean, Central Asia and the Arctic, namely the areas that straddle geopolitically the Euro-Mediterranean neighbourhood and Asia-Pacific, in the sense that instability in those areas deeply affects both Europeans and Japanese.

The question, therefore, is a more operational one: how can Europeans and Japanese cooperate to underpin a balance of power in the ‘middle spaces’? It is difficult to overstate the importance of the Indian Ocean in the context of Europe-Japan relations. Over 90% of the trade between Europe and East Asia is seaborne and is largely conducted through that ocean. The Indian Ocean leads Europeans and Japanese to the mineral riches of East Africa and to the Indian sub-continent –an important source of cheap labour and manufactured products–. Given their demographic projection, East Africa and the Indian sub-continent offer considerable potential as investment and export markets in the medium and long term. Critically, the Indian Ocean is the gateway to the Persian Gulf, which is the main source of oil for Europe and Japan –as well as an important source of gas–.

More broadly, the increasing dependence of countries like China, India, Japan and South Korea on Persian-Gulf energy means the economic development and stability of East Asia is increasingly tied to the Middle East. Thus, Europeans and Japanese share two fundamental geostrategic objectives: the security of the Indian Ocean Sea Lanes of Communication (SLoC) and the existence of a balance of power in the Indian Ocean ‘rim’. The fight against piracy in the Gulf of Aden is an important step for Europe-Japan cooperation in an Indian Ocean context –and could be complemented with similar efforts in the area of the Strait of Malacca–. However, such cooperation should be extended into other areas such as intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, joint surface and subsurface patrols, and naval exercises and training.

Admittedly, Central Asia’s importance as a trade conduit between Asia and Europe pales in comparison to that of the Indian Ocean. Current efforts to reinvigorate the notion of a Eurasian ‘silk road’ could conceivably lead to a revaluation of the continental connection between Europe and Asia. However, measured against the Indian Ocean, continental routes remain both more expensive and riskier –as they cross multiple countries in geopolitically unstable areas such as South Asia, the Middle East and Central Asia itself–. Having said that, both Europeans and Japanese are interested in Central Asia’s energy and mineral riches.

If Europeans and Japanese are to fully exploit the energy and mineral potential of Central Asia they must help uphold a (favourable) balance of power in the region. This becomes particularly important as NATO forces wind down their presence in Afghanistan and Russia and China consolidate their influence across Central Asia. The spectre of Russian political hegemony, Chinese economic dominance or some form of Sino-Russian condominium would cut the Central Asian republics off from the global economic system. In order to prevent this from happening, Europeans and Japanese must continue to work alongside the US, India and like-minded partners to help underpin the autonomy of Afghanistan and the Central Asian republics and promote political and economic cooperation between them.

The Arctic is another region where Europeans and Japanese have much in common. It is estimated to hold some 20% of the world’s gas reserves and around 25% of its oil reserves. As such, Europeans and Japanese see the development of the ‘High North’ as an opportunity to reduce their energy dependence on Russia and the Persian Gulf. Beyond energy, as the polar ice caps continue to melt, the Arctic Ocean promises to facilitate the communication between Europe and North-East Asia by cutting the shipping route from Hamburg to Shanghai by some 6,400km.

As China, Japan and South Korea reach northwards and Russia, the US, Canada and northern Europeans consolidate their positions in the Arctic, the ‘High North’ is likely to become an increasingly crowded and contested geopolitical space. Europeans and Japanese must therefore work alongside their North-American partners to ensure regional stability and the adequate integration of the ‘High North’ as an energy and communications hub in the rules-based international liberal order.

Another key security issue that is a common concern to the EU and Japan, and in which they share a principled position, is the maintenance of the non-proliferation regime. Unlike some of their traditional allies, all EU member states and Japan have signed and ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty. The nuclear and missile programmes of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea pose the most blatant threat to the non-proliferation regime and also a direct threat to Japan, mainly due to the maintenance of US military bases on Japanese soil and the risk of an accident in a missile test, and to a common ally, the US. Therefore, it is imperative for the EU, its member States and Japan to maintain a common position on the issue. So far, the EU and Japan have cooperated to counter the threat through the imposition of economic sanctions and by opening the door for meaningful dialogue with Pyongyang. As the North Korean nuclear programme develops, Europe and Japan should work closer together to defend a common stance that keeps putting economic and diplomatic pressure on Pyongyang and preclude both the recognition of North Korea as a nuclear power and military intervention.

Another area for cooperation between Europe and Japan is Strategic Communication. The dissatisfaction of some sectors of the European and Japanese populations with the international liberal order is fuelled by hybrid practices, such as information warfare and fake news from Russia and China. In this context, new Strategic Communication policies are needed in Europe and Japan to increase domestic support for the maintenance of the international liberal order, providing tools to better communicate its benefits and potential for reform and the eventual implications of its fall.

Conclusions

The rise of emerging powers and a significant questioning of key pillars of the liberal order in some OECD countries bring uncertainty to the durability of the current international order. Despite its shortcomings, this open and rule-based international liberal order has created conditions for reaching unprecedented levels of socioeconomic development and stability across the world. Therefore, likeminded actors such as Europe and Japan should redouble their efforts to reinvest the features of the liberal order that favour inclusiveness and fairness. Doing so, they will make it less likely for rising powers to resort to force to secure their interests and will deal more effectively with daunting traditional security threats and the provision of global common goods. The adoption of an EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and a Strategic Partnership Agreement would be the clearest signal that Brussels and Tokyo are joining forces in such a task.

Mario Esteban

Senior Analyst, Elcano Royal Institute, and Professor at the Autonomous University of Madrid | @wizma9

Luis Simon

Director of the Elcano Royal Institute’s Brussels office and Research Professor at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel | @LuisSimn

1 For a deeper discussion of the future of the liberal world order see Charles Powell (2017), ‘¿Tiene futuro el orden liberal internacional?’, ARI nr 56/2017, Elcano Royal Institute.