Theme

This paper looks at the 2024 European elections results and their impact on the new five-year institutional cycle of the EU. It reviews the formation of political groups in the 10th European Parliament, as well as the election of the Commission President during the initial plenary session.

Summary

This analysis concerns two issues. First, it looks at the 2024 European election results from a European perspective, not a national one. The 10th Parliament has eight political groups, three of which are on the right or far-right side of the chamber: one has expanded (ECR), the second has rebranded and expanded (Patriots for Europe), while the third is completely new (ESN). Meanwhile, the EPP has retained the first place and the S&D the second among the groups in the EP. Renew Europe has been imploding since the elections and the Greens have lost momentum. The balance of power in the renewed Parliament has shifted from Renew Europe to the European People’s Party.

Secondly, it analyses the trends of the European political scene after the elections. The early summer of 2024 was a historic moment of transition of power in the EU. Between 2019 and 2024 the EU political system was dominated by the political scheme of the Green Deal and three big crises: Brexit (from 2016 until 2020), COVID-19 (from 2020 until 2022) and the war in Ukraine (from 2022). On the one hand, the new Parliament, and with it the EU with a renewed social mandate, witnessed a policy of continuance, with the same leadership in the Commission and in the Parliament backed by a similar ‘Ursula 2.0’ coalition. On the other hand, the banner of the Green Deal was replaced by an unclear new keyword: ‘clean industrial deal’. All this has taken place while the number one priority is the ever more serious need of a collective joint defence.

In the new political set-up it is likely for inter-institutional relations to experience a change towards an increased politicisation and reduced inter-institutional conflicts. Relations in the European Council are also evolving towards polycentric majorities.

Analysis

1. Introduction

Europe’s citizens have voted in the 10th Union-wide elections and the lengthy period of leadership transition has begun. By the end of 2024 a complete set of leaders will have been chosen, including the full college of European Commissioners (expected from 1 November) and a new President of the European Council (from 1 December). The changes resulting from the elections, both in personnel and policy shifts, reflect the state of Europe’s democracy, the only transnational example in the world.

The main topics in the campaign were security and the state of the economy, which marks a clear shift from the main issues five years ago (such as climate change).[1] The EU is weary of multiple crises and the Russian war in Ukraine. Although it is unlikely for the Union to abandon its course of energy and climate transformation towards climate neutrality by 2050, some major adjustments to specific solutions in the coming years are not out of the question.

Between 6 and 9 June 2024, 51% of over 360 million voters in the EU elected the 10th European Parliament. Voter turnout was slightly higher, at 51.08% in 2024, than five years ago (50.66%). Before 2019 the turnout in European elections had been declining for two decades.

This analysis presents the evolution of the political situation in the Parliament and, more broadly, in the EU following the elections. At first glance, the changes seem cosmetic. However, ‘slight shifts’, which may not even result in changes in the positions of the Presidents of the European Commission and the European Parliament,[2] are significant for the process of European integration and the EU’s agenda in the coming years.

Two primary phenomena arise from the analysis, mainly concerning the increased politicisation of the EU. On one hand, in the new European Parliament the division between pro-Commission groups and those in opposition will be even more significant. On the other hand, growing politicisation is likely to occur to a greater extent in the Council of the EU, whose –present day– modus operandi is based on the diplomatic negotiations of a majority (the preference for unity). Paradoxically, this may lessen the relevance of the institutional dispute between the Parliament and the Council.

The second important process highlighted by the elections is the political crisis of the engine of EU integration, which has traditionally been the Berlin-Paris axis. In the spring of 2024 we saw a new polycentric management of the entire Union but without the moral authority of the two important capitals. The two most important politicians in the current EU are the prime ministers of Poland and of Italy. The former, Donald Tusk, is simultaneously: (a) the leader of a political coalition that defeated a nationalist party in his home country; (b) the leader of the largest country in the European People’s Party; and (c) a former President of the European Council.[3] The latter, Georgia Meloni, is the leader who is ‘contesting the mainstream’.[4]

In this renewed polycentric situation, there is more room for political initiatives from all the capitals. As different issues call for a greater focus, it may be understandable to expect renewed initiatives related to migration or maritime border security from the Mediterranean nations, while initiatives related to Eastern European security or border tensions could come from the countries situated there.[5]

2. Election results and the formation of the 10th European Parliament

The European elections did not bring a significant quantitative change in support for the two largest political blocs, the centre-right and centre-left. The increase in support for the nationalist right, previously organised within two political groups –European Conservatives and Reformists, ECR, and Identity and Democracy, ID–, was evolutionary rather than massive and mainly at the expense of the liberal-centrist and green groups.

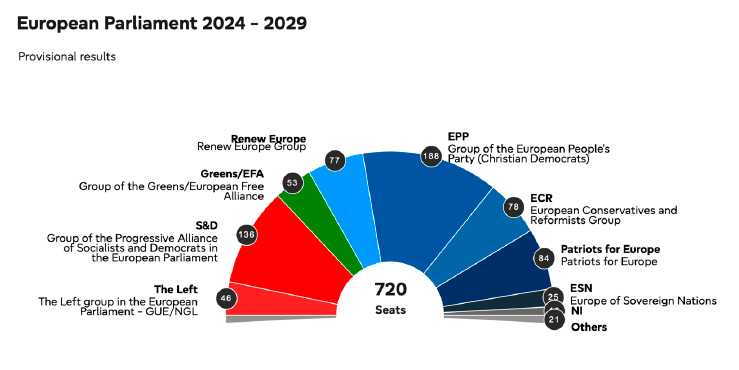

Figure 1. Mandate distribution in the 10th European Parliament at the beginning of the term

Figure 2. Change in group composition, April 2024 (9th EP) to July 2024 (10th EP)

| Political group | Left | S&D | Greens & co. | Renew Europe | EPP | ECR | Patriots 4 Europe (ID) | ESN | NI/Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April (705) | 37 | 139 | 71 | 102 | 176 | 69 | 49 | 0 | 62 |

| July (720) | 46 | 136 | 53 | 77 | 188 | 78 | 84 | 25 | 32 |

| Change (+15) | +9 | -3 | -18 | -25 | +13 | +9 | +35 | +25 | -30 |

2.1. European People’s Party (EPP, 188 MEPs)

The European People’s Party remains the largest group numerically and, indeed, has been strengthened. Its former coalition (EPP-RE-S&D) has maintained a nominal majority in the new European Parliament, which has resulted, among other things, in the continuation of the political mandate of the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen (EPP-DE). The coalition’s strength has also translated into the distribution of key positions in the Parliament between the EPP and S&D, especially that of President of the Chamber, to be shared by the EPP and the S&D for half of the parliamentary term each. The EPP’s candidate for the Parliament’s presidency for the next two and a half years is the previous President, Roberta Metsola (EPP-MT).

The only European grouping not to have lost any seats has been the EPP, with its most significant gains being registered in three countries: Spain, nine; Poland, seven; and Hungary, six. This will likely lead to an increased importance for these national delegations within the group.

The general shift of the Parliament to the right has led to a major change in the Parliament. If previously the Renew Group was sitting ‘in the middle’ of the chamber, the middle point is now held by the EPP.

Manfred Weber’s position as group leader (EPP-DE) seems assured. The largest delegation within the EPP are the Germans (30 MEPs), followed by the Poles (23) and the Spaniards (22). Except for the Romanians (11 MEPs), no other national delegation has more than 10 elected officials in the group.

2.2. Social Democrats (S&D, 136 MEPs)

The second largest group are the Social Democrats, who, however, lost the ability to form a progressive alternative in the event of disagreements with the EPP. In the previous term, a majority of four groups to the left of the EPP was possible, as seen in some votes on the Green Deal. For instance, in the committee vote on the restoration of natural resources, there was a 44:44 tie between progressive and conservative MEPs.[6] A slight majority was only achieved in plenary votes, such as the final agreement negotiated with the EU Council, passed by a majority of 329 to 275 votes on 27 February 2024.[7]

The Social Democrats suffered minor losses in the elections, which do not significantly alter the relationship with their coalition partner (EPP), except for losing the ability to form an alternative majority without the EPP. The largest national delegation in the new Parliament is the Italian (21), followed by the Spanish (20) and among the larger delegations are also the German (14), the French (13) and the Romanian (11).

The biggest group gains were in Italy and France (up six MEPs each), and the largest losses for the S&D were in Poland (down four seats). The previous leader of the S&D, Iratxe Garcia Pérez (S&D-ES) was re-elected for the new term.

In 2023, due to a coalition government between the Slovak left-wing parties SMER and Hlas and the far-right Slovak National Party (a member of ECR), the Party of European Socialists suspended its Slovak members. Now, following the European elections, six MEPs from SMER and Hlas remain unaffiliated, but politically consider themselves to be left leaning. There is only a slight chance that some of them may join the S&D individually during the term.

2.3. Patriots for Europe (PfE, 84 MEPs)

Where there was competition was in the quest to become the third largest group in the 10th European Parliament. Previously the centrist Renew Europe had held the position for many years. Following the elections, it appeared that the ECR might become the third largest, although when the Parliament met on 16 July it turned out to be Patriots for Europe (PfE).

The PfE is largely based on the initiative of three leaders of Fidesz (previously unaffiliated), ANO (previously in Renew Europe) and the Austrian FPO (previously in Identity and Democracy). What united them was their opposition to Ursula von der Leyen’s Commission and the Green Deal. Following the announcement of the creation of the new group, most Identity and Democracy (ID) members joined it, making it the latter’s ‘reincarnation’. The ID’s largest national delegation was the French National Rally, and it remains so in the PfE (30 MEPs). Hence the PfE’s new leader is Jordan Bardella (PfE-FR). The second largest national delegation is Hungary’s (11).

PfE, like the ID before, remains politically isolated in the Parliament with a cordonsanitaire applied by the von der Leyen majority to this group as well as the ESN. However, the group’s renewal was a strong sign of a new rivalry between the ECR, PfE and ESN to determine which should become the primary alternative to the EU’s ruling mainstream.

Members of PfE are often portrayed as a politically extreme. They advocate a Europe of sovereign states with less EU influence. Many members are also accused of being pro-Russian, in opposition to the Green Deal, even demanding to abandon the European Parliament and return to the pre-1992 situation (Treaty of Maastricht).

The move of Spain’s VOX from the ECR to PfE was in the opposite direction (towards a greater radicalism) to other cases. For most former ID members, the PfE is considered slightly less ‘toxic’ (for example, the group does not include the German AfD, and was joined by the Czech ANO and governmental parties –Fidesz in Hungary and PVV in the Netherlands–). Santiago Abascal, VOX’s leader, had stated that PfE was the best place to demand a ‘radical and urgent change of course in the EU’.

Nevertheless, from a positive point of view, there could be a slightly different explanation: VOX wants to be a bridge between the PfE and the ECR. For instance, Abascal respected Meloni’s request not to leave the ECR before 4 July, when the groups met to allocate committee seats and organise the parliament’s leadership. This was the moment when the ECR was still the third largest group during the negotiations. The VOX leader still talked about working for the creation of a single ‘large group’ to include all radical forces. On finding it impossible to do so, he opted for the Patriots. Abascal continues to be grateful for Georgia Meloni’s support: ‘she will always be a partner, a friend and an ally of VOX’. He was also thankful to Poland’s PiS, the second largest force in the ECR, which was ‘at the vanguard of patriotic struggles in Europe’.[8]

However, no ECR-PfE unity is possible as long as the war in Ukraine continues and there are major differences of opinion between Georgia Meloni and Viktor Orbán. ‘Going with Le Pen is contrary to Meloni’s plans in Italy’, said a leading MEP in Strasbourg in July 2024.[9] Hence, an alternative motive for VOX transferring to the Patriots’ group was the fear inspired by Alvise Pérez’s Se Acabó la Fiesta (‘The Party’s Over’, SALF) and the desire to prevent the latter from joining any major group. Accordingly, there would be a struggle between VOX and SALF to see which proves to be more radical when it comes to EU policies.

2.4. European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR, 78 MEPs)

The European Conservatives and Reformists are the fourth largest group, having gained several more MEPs and added a some more new national parties to its grouping. The most significant change for the ECR is the broad expectation in the new Parliament (especially in the EPP and some of Renew Europe) that it will join the mainstream. The largest delegation in the ECR is Poland’s Law and Justice party (PiS), which had been accused of breaching the rule of law during its period in government in Poland (2015-23). In response, the European Commission had initiated Article 7 proceedings (the suspension of voting rights for violating EU values), and politically applied a cordon sanitaire to its politicians in the European Parliament.

However, the fall of the PiS government in Warsaw in 2023 led to it no longer being breaching the rule of law. Therefore, it can be argued that the entire ECR group has now entered the European mainstream.

Historically, the ECR was established by the UK’s Tories after the party split from the EPP in 2009. Following Brexit in 2020, the ECR underwent a transformation. Although its largest national delegation in the 9th EP was by far PiS (27), it was co-chaired by Ryszard Legutko (PiS) and Nicola Procaccini from Fratelli d’Italia (‘Brothers of Italy’, FdI). The latter only had 10 MEPs.

The elections resulted in significant shifts within the ECR. PiS suffered the biggest losses (down seven), while FdI achieved the greatest victory (+12), becoming the largest national delegation in the ECR (24). Smaller delegations have no more than six seats (Romanians). Thus, Nicola Procaccini (ECR-IT) and Joachim Brudziński (ECR-PL) have been elected co-chairs.

However, the driving force in the ECR is the Italian Prime Minister, Georgia Meloni, whose government comprises parties in the ECR, EPP and PfE. Since the formation of Meloni’s government there has been a process of political rapprochement between FdI and the European mainstream, especially with German CDU/CSU politicians. The overall assessment of Prime Minister Meloni’s policy is ‘surprising for Brussels sceptics’, mainly due to her pragmatism.[10]

During the pre-election debates, Ursula von der Leyen spoke about three conditions for future cooperation with right-wing politicians: (a) FdI’s pro-European stance; (b) a pro-Ukrainian policy; and (c) respect for the rule of law in each country. In her pre-election calculations, von der Leyen distanced herself from the entire ECR but extended a hand to Meloni. After the elections, some ECR MEPs supported von der Leyen’s re-election (the Czechs and Belgians), although the majority of members voted against the President.

The ECR’s relative popularity on the right of the Parliament stems from their strong emphasis on the member states’ sovereignty and their demand for a reduction in the European Commission’s powers. Politically, the ECR presents itself as a ‘more civilised’ alternative to the mainstream groups in the European Parliament –the cordon sanitaire has not been applied to the ECR–, unlike the other far-right groups. According to this idea, the ‘less civilised’ option (subject to the cordon sanitaire) is ID, now transformed into PfE. This was precisely what drove the new Spanish radical party SALF to seek membership in the ECR.[11]

Policy wise, the ECR is critical of PfE’s position on the war in Ukraine and Russia’s role in it. The ECR is also unambiguously pro-US and most of its MEPs are not climate-deniers.

2.5. Renew Europe (RE, 77 MEPs)

After having been the third largest group, RE is now the fifth. It suffered significant losses, especially in France and Spain. Following the elections a large delegation of Czech MEPs from the ANO party left the group for PfE. Despite this, Renew Europe remains an essential partner for the EPP and S&D in constructing a political majority for the next European Commission.

The inspiration for the creation of RE in 2019, based on the liberal ALDE party (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe), came from French President Emmanuel Macron. The post-election estimates suggested losses of around 20% of members for RE. In France RE lost 10 seats and in Spain eight. Poor results were also achieved by RE parties in Romania (minus five) and Italy (minus four), which will have no representation in the group.

After the elections, the group seems to be imploding. In the European Council, RE is set to lose two prime-ministerial positions to right-wing groups (the Netherlands and Belgium) in the upcoming weeks. In the European Parliament, RE was abandoned by one of its key national delegations, the Czech Republic’s ANO (seven). Politicians from this party campaigned for the European Parliament criticising the Green Deal and the EU’s migration policy. After the elections, ANO announced they would not support Ursula von der Leyen for a second term as the Commission President and left the group.[12]

Old disputes between ALDE members (around two-thirds of RE) and French politicians, who refuse to use the adjective ‘liberal’ for the group, have not died down. Criticism of the cooperation of RE member parties with far-right groups persists. Should liberal and centrist parties enter into coalitions with anti-system far-right parties? The debate flared up in the context of the newly formed coalition government in The Hague, which includes the large Dutch VVD party (an ALDE member).

The problem is broader and also concerns the Swedish and Finnish group members. All of them were threatened with expulsion from the group due to national coalitions with parties from the ECR (the Swedish Democrats and the Finns Party, formerly the True Finns) and the PfE (the ex-ID Freedom Party [PVV] in the Netherlands). While in Sweden and Finland the prime ministers are EPP politicians and the ECR groups have a limited impact on the overall functioning of governments, the PVV will take responsibility for the next government in The Hague, headed by the technocrat Dick Schoof. It is likely that the next Belgian government will also include Belgian liberal parties (RE members) and those that belong to the ECR.

The French delegation (13 MEPs) remains weakened, but is still the largest in the group. The current leader, Valerie Heyer (RE-FR), was re-elected for another term. Other major delegations are the Germans (eight seats) and the Dutch (seven).

2.6. Greens & co. (G, 53 MEPs)

Sixth in the group ranking are the Greens, who suffered severe losses in several member states, losing 18 MEP seats. The largest losses were recorded in Germany (nine) and France (seven), with a gain in the Netherlands (three). This was primarily due to fatigue over the costs of climate transformation, as well as the changing priorities of Europeans. In 2024 the main motivations of voters were: (a) international conflicts; (b) economy; and (c) migration.[13]

The largest national delegations are those from Germany (16 MEPs) and the Netherlands (six), which also reflects the group’s two leaders: Terry Reintke (G-DE) and Bas Eickhout (G-NL).

In coalition with the Greens is the European Free Alliance (EFA), which has four MEPs from Catalonia, Valencia and Galicia. Another new coalition partner is the growing European federalist party Volt. In 2024, Volt candidates won five parliamentary seats (two in the Netherlands and three in Germany).

2.7. The Left (L, 46 MEPs)

The far left also has its own group. So far, the Left (known as GUE-NGL until 2023) has included anti-capitalist, post-communist, anti-system and protest parties (workers and the unemployed). Manon Aubry (L-FR) and Martin Schirdewan (L-DE) are the group’s co-chairs.

Temporarily, the Left has agreed to associate with an Italian party, the Five Star Movement (M5S). The M5S had tried several times to affiliate itself with existing progressive groups, but to no avail (the Greens, the Left and Renew Europe). In the past, M5S formed a confederal group with the British UKIP party, which campaigned for Brexit (EFDD group, 2014-19).

The biggest question mark facing the Left is currently whether it will expand and accept the new party from Germany, the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) with its six MEPs, which would mean overtaking the Greens.

2.8. Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN, 25 MEPs)

To create a group, it is necessary to muster at least 23 MEPs from a minimum of seven EU countries. Germany’s AfD was able to create a small group upon its own expulsion from the ID just before the elections.

The new group has 25 members, although 14 are from Germany’s AfD. At its constituent meeting Rene Aust (ESN-DE) and Stanislaw Tyszka (ESN-PL) were elected co-chairs.

The group could grow if it finally includes the Spanish SALF, should the latter’s request to join the ECR fail. A third option for SALF is to continue to be unaffiliated. The question remains open, however, and SALF’s leader has at one point asked for patience in announcing a future decision in this respect.[14]

3. The new political moment in the EU

3.1. Who will govern the Union?

Until 2014 there were basically no rigid divisions in the European Parliament between majority and minority politicians. The European political system is rooted in a strong sense of respect for differences between political parties. The fact that no party has ever had a majority is a key reason for the need to build coalitions and compromises. No group or nation has ever been able to dominate the work of the chamber. Thus, the differences among MEPs concerned their style of work and political activity rather than a political colour.[15]

This political system began to evolve with the emergence of candidates to the Presidency of the European Commission in the European elections at the head of their party lists (the so-called Spitzenkandidat). The lead-candidate mechanism proposed by the European Parliament resulted in the election of Jean-Claude Juncker as Commission President in 2014. The system failed in 2019, when Ursula von der Leyen, who did not run for the position in the elections, became the new President of the Commission. Moreover, her name appeared in the negotiations between leaders at the European Council meeting after all possible lead candidates were rejected. The European Council has never agreed to limit its ability to propose a candidate for President of the Commission only from among the Spitzenkandidaten.[16]

On 27 June 2024 the European Council proposed to renew Ursula von der Leyen’s mandate for another five years. Thus, the European Council, as in 2014, proposed the candidacy of a person who was the leading candidate of the party that won the elections. Over two meetings of leaders, the key members of the European Council that proposed the ‘institutional arrangement’ were the representatives of the three political forces present in the European Council. For the EPP the negotiators were Donald Tusk and Kiriakos Mitsotakis (12 seats in the European Council), for the PES Pedro Sánchez and Olaf Scholz (four seats), and for Renew Europe Emmanuel Macron and Mark Rutte (four seats). The representatives of the ECR (two seats) were not invited.

The decision in the European Council was relatively quick and easy. Ursula von der Leyen’s candidacy for the Commission Presidency was supported by 25 leaders. While von der Leyen still required approval of the Parliament, Antonio Costa, as President of the European Council and Euro Summits (from 1 December 2024), and Kaja Kallas, as High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy were given accepted without the need of the EP’s approval.[17]

A much bigger challenge for the Commission’s President-elect was gaining the necessary 360 votes in the European Parliament, although she ultimately won 41 votes more than required after securing the support of the majority of MEPs from the EPP, S&D, Renew Europe and the Greens.[18]

In 2019 von der Leyen received only nine votes above the required majority, but that was due to her not being the leading candidate. In that vote, many MEPs were guided by a message from the chamber announcing that it could reject the candidacy of someone who was not a lead candidate.[19]

Figure 3. Mainstreaming of political parties in the European Parliament among the most populous member states (%)

| Left | S&D | G | RE | EPP | ECR | PfE | ESN | NI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE (96) | 4 | 71 | – | – | 15 | 10 | |||

| FR (81) | 11 | 46 | 5 | 37 | 1 | – | |||

| IT (76) | 13 | 45 | 31.5 | 10.5 | – | – | |||

| ES (60) | 7 | 78 | – | 10 | – | 5 | |||

| PL (53) | – | 51 | 38 | – | 5.5 | 5.5 |

The 2024 Spanish EU elections clearly provided the strongest national support to a mainstream ticket in next European Commission among the more populous nations (see Figure 3). This will be very important for the working methods of the Parliament, as the reports (legislative and political) are allocated in proportion between political groups, who are not behind an effective cordon sanitaire. It is telling that the share of MEPs elected from Germany and France among the non-cordon sanitaire political groups is well below 80%, while the Italian and Polish MEPs are above 80% only because of the inclusion of ECR in the mainstream. Whether this translates into a working environment in which ECR MEPs take reports and negotiate chamber compromises, remains to be seen.

Hence, the Spanish non-cordon sanitaire MEPs are guaranteed (85%) to receive more frequently reports in the new legislature than their colleagues from other member nations.

Also, among the leadership positions in the Parliament the combination of two factors are relevant. First is the size of national delegation. Second is the share of MEPs who actually are within the EP mainstream. This explains why there are nine Vice-presidents/chairs of committees from Germany (from four different political groups). Second to the Germans are five Spaniards (from two groups, EPP and S&D) and five Poles (from two groups, EPP and ECR), only followed by four French and Italian politicians each and three Romanians in leadership positions.

The four largest committees (which is usually considered with the most politically relevant) will be chaired by David Allister (foreign affairs, EPP-DE), Antonio Decaro (environment, S&D-IT), Borys Budka (industry and energy, EPP-PL) and Javier Zarzalejos (civil liberties, justice and home affairs, EPP-ES).

From the very beginning of the 10th European Parliament, it seems the chamber is going to take up political challenges not resulting from institutional disputes but from party and political conflicts. The challenge for von der Leyen in 2024 was not that she was not a leading candidate. The fact that she was the leading candidate of the European People’s Party did not mean she was automatically supported by the majority of the Parliament.

President von der Leyen must have worked hard to build this majority. And while in 2019 the President still appealed to a general majority of all MEPs, and her college of commissioners reflected the government majorities in the capitals, in 2024 von der Leyen will have to rely much more on the support of her coalition parties, regardless of whether some of the national parties are government parties in the national capitals.

Von der Leyen’s majority in the 9th Parliament was provided by three parties: EPP, S&D and Renew Europe. In July 2019 these three parties had 442 MEPs, ie, 59% of all seats in Parliament. In the new Parliament, the three parties have 401 MEPs, or 56% of all votes. However, this does not mean that voting was problem-free. According to Politico Europe, approximately 13% of MEPs voted against the position of their political groups for Commission Presidents in 2014 and 2019.[20] The election was secret.

Actually, von der Leyen was supported by a majority of her coalition MEPs with notable exceptions (such as the German FDP, members of Renew Europe), but what she lost from among the majority she was able to gain elsewhere, most notably in the Green group and from two national delegations of the ECR (the Belgians and Czechs).

A poll conducted immediately after the elections showed that EPP electorates are divided on who to work with along the political fault lines in these countries. Thus, in Poland, France and Germany, the electorates of the EPP parties refused to cooperate with the ECR and ID (PfE) parties. The axis of the dispute in France is between Marine Le Pen’s National Movement and everybody else, and in Poland between EPP (PO) and PiS. In Germany the division is between all the parties except for the AfD, considered a threat to democracy.

The situation is completely different in countries where the axis of the dispute is between the centre-left and the right. A survey among EPP voters in Italy (EPP in government with ECR and ID/PfE), Spain (locally EPP cooperated with ex-ECR, now PfE) and Sweden (EPP government with ECR support) clearly suggests that the European People’s Party should not be afraid of cooperation with far-right parties.[21]

3.2. Shifting priorities: economy and security

Building a pro-von der Leyen majority in the European Parliament relied as much as possible on the Green Deal policy. The way to save the policy and shift the gear was to change the narrative. Von der Leyen’s constituting document outlines two first priorities: economy and security. Only following those two are the other priorities social model (including very vocal new initiative on housing, including a commissioner responsible for the matter), quality of life, democracy and values as well as the global affairs. The green agenda from five years ago was streamlined in the economic and quality of life priorities.[22]

In the previous Parliament, depending on the issue, the majority was possible to obtain either by four progressive and centrist groups (Left, Social Democracy, Greens and Renew Europe) or by right-wing and centrist groups (EPP, ECR and Renew Europe with the possible support of ID), which put the Renew Europe group in a privileged position. Most often, however, majority was delivered by the cooperation of the so-called the ‘Ursula von der Leyen coalition’ including the EPP, S&D and Renew Europe with occasional support from other groups.

In the 10th Parliament, there will be little opportunity for both broad agreements between progressive and right-wing groups to achieve a majority. Any cooperation between progressive groups and nationalist groups should be considered unimaginable, ever since the S&D and the Greens refuse to cooperate with PfE and ESN politicians (cordon sanitaire), sometimes even the ECR. Therefore, the European People’s Party is in a privileged position, without which no permanent majority seems possible.

On the one hand, there is the new ‘Ursula 2.0 coalition’, which in the new Parliament also includes the Greens. On the other hand, depending on the topic, the EPP may reach for the votes of the right side of the Parliament. Areas of potential cooperation between the EPP and the groups to the right of it may include, among others: the limitation the costs of climate transformation and migration policy (EPP, PfE and ESN have a similar perception of the threat from what they call ‘illegal migrants’). However, for the EPP, the cost of getting too close to the ECR may mean losing a permanent coalition with S&D in favour of an ad hoc partnership.

The relative increase in support for anti-system parties and the increase in general dissatisfaction should be considered a weakening of the democratic mandate for the direction of to-day reforms in the EU. The main transformational reform programme so far, the Green Deal, is facing at least: (a) a partial review, as well as; (b) de-prioritisation and; (c) moves towards implementation.

The new positioning of the climate and energy transformation as part of broader economic reforms was well illustrated by, for example, the EPP election manifesto, in which the priority of climate transformation was included as the fourth point of the second part devoted to the social market economy. The first part was entirely devoted to European security, including the expansion of the defence industry, the institutionalisation of defence (EPP demanded the appointment of a commissioner for defence and security and the creation of an 11th Council within the EU Council bringing together defence ministers) and strengthening borders.

Placed alongside other economic priorities (including jobs, international trade and digitalisation) and pushed into the background, climate transformation should now serve to increase the competitiveness of the economy: ‘We shifted the climate agenda to being an economic one’, as stated in the EPP election manifesto of 2024.[23]

3.3. The changing axis of the political dispute in the EU

For many years, the axis of political dispute in the EU has been between those who support the so-called the ‘Community method’, a stronger and more centralised EU, and those who defend national interests as sovereignty. In recent decades, this dispute had an institutional dimension: it was the European Parliament that demanded ‘more Union in the Union’, and the Council composed of member states was considered ‘resistant’.

This division may now fade into the background. The interinstitutional relations have been characterised by mutual suspicion. Now, the situation may improve. The disputes between supporters of the ‘Community method’ and the ‘national method’ will become increasingly visible both within the Council and the Parliament. Therefore, there may be similar debates in both institutions, and each interinstitutional agreement –necessary for the adoption of laws in the EU– may be adopted with a larger number of votes in the more divided EU Council.

On the one hand, in the new, more right-wing Parliament, the progressive groups will defend the current climate arrangements. The 10th Parliament will address some of the outstanding issues, such as the intermediate decarbonisation goal of cutting the CO2 emissions by 90% by 2040. However, the left-wing politicians will not have enough votes to defend all the current arrangements of the Green Deal from softening. A foretaste of this new approach to transformation was visible during the winter and spring farmers’ protests, when the European Commission withdrew a draft law banning the use of pesticides,[24] A few days later, the EC also took a step back from the mandatory fallowing of 4% of land.[25]

The political alignment between Parliament and the Council may paradoxically serve to increase the level of trust between the two institutions. This should not mean to expect the Parliament to be subservient to the Council. On the contrary, mutual respect should be based on respecting one’s institutional and political autonomy. The next test of the new interinstitutional relations will be the hearing process of candidates for commissioners.

If a real attempt was made to solve difficult past issues, it may be possible to return to some unresolved problems, such as the strengthening of the European Parliament’s investigative powers, which today are based only on the participants’ good will. For example, there is no legal obligation to cooperate or appear before the EP committee.[26]

3.4. New relations between the centre and the periphery

The European elections showed something else. At least since the 1980s, the relationship between German and French leaders has been crucial for the development of European integration. It was the synergy between the Christian-Democrat Helmut Kohl and the socialist François Mitterrand that allowed the work on the Treaty of the European Union (in Maastricht, entry into force in 1993), the creation of many new policies and initiatives under the leadership of Jacques Delors as Commission President (cohesion, euro, Schengen, Erasmus, to name a few). It was the cooperation between Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron that allowed for an effective response to the coronavirus pandemic, as well as the construction of a new financial instrument for economic reconstruction after the pandemic. In the last European 2024 elections the decision-making centres in Berlin and Paris have suffered significantly.

The popularity of President Emmanuel Macron, who was the main EU politician in 2019, the author of several groundbreaking speeches on European sovereignty and who initiated the creation of the Renew Europe group, has suffered to such an extent that his own party’s candidates were refusing to take photos with the president in the last French parliamentary elections.[27]

Many other leaders lost in the European elections. Among others, in Spain the PSOE (S&D) of Pedro Sanchez lost to the Partido Popular (EPP), but the defeat of Chancellor Scholz’s SPD in Germany was spectacular. The chancellor’s party lost not only to the EPP’s CDU/CSU, but also to the far right AfD. There are also more German MEPs in the Green group (since Volt joined the Greens).

The EU’s voting results do not paralyse the activities of national governments. Nevertheless, the election results are a signal for leaders in the European Council. Those who are victors claim a renewed mandate. Hence, Prime Ministers Meloni of Italy and Tusk of Poland were stronger figures during the June European Council. Together with Sánchez and a weakened Macron and Scholz they are leading the EU’s largest nations in the current constellation.

The situation in the European Council does not, however, mean that large member states dominate. On the contrary, the voices during the debates (at the European Council and thematic Council configurations) and the ability to propose topics is much wider. It is as if the European Council had become a major platform for a rich pan-European debate, with only the leaders there to witness it.

The next ‘political game’ will be that of the European Commission’s composition. It seems that the five largest member states are not competing for the same goals. Spain is posed to receive one of the highest positions in the Ursula von der Leyen second College of Commissioners, as the Madrid government is set to provide a Social Democrat politician, most likely Teresa Ribera, as one of the executive Vice-presidents of the Commission.[28] The German (von der Leyen) and French (Breton) Commissioners shall continue, while the next Italian and Polish Commissioners are likely to be representatives of the ruling parties (belonging to ECR, EPP, respectively).

The key people playing the upper hand in the process are the same leaders who handled the appointments back in June: Tusk and Mitsotakis for the EPP, Sanchez for S&D (Scholz has no say as von der Leyen is German) and Macron for Renew Europe (Mark Rutte since the European Council). It is safe to predict a Spanish and Polish (or Greek) executive Vice-president alongside a Commissioner from a less populous nation affiliated with centrist of liberal parties.

While prime minister Giorgia Meloni is still struggling to organise her own political base at the European level, it is up to ‘the established mainstream’ to engage with her (or not). The ‘established mainstream’ not only includes some of the longest serving members in the European Council, but also the most respected ones. Hence the ‘Socialist cardinals’, as Scholz and Sanchez are sometimes called, and centrist president Macron are accompanied by the most prominent EPP member, Donald Tusk. His position is not to be overlooked nor underestimated, at least until June 2025, when the Polish presidency in the EU Council is to end. The main reason for his unique aura comes from the fact his political coalition fought against the far-right government in 2023, something Macron and Scholz are facing in their domestic affairs.[29]

Conclusions

The European elections have changed the balance of power in the European Parliament, in which the far-right groups will have a greater political clout, yet the mainstream majority coalition has managed to retain its advantage. The main conclusions to be drawn from this analysis are that:

- The EU is facing a reformulation of political priorities, with a downgrading of the green agenda.

- A real development of the European security and defence capabilities should be expected in light of the war in Ukraine.

- Climate transformation will be part of the economic strategy of the ‘clean industrial deal’.

- The European People’s Party (EPP) is the main party, without which there is no majority in the new EP.

- S&D lost its alternative progressive majority, Renew imploded, the Greens consider how to save the Green Deal, the ECR fears the threat of the Patriots, PfE cannot get out of the cordon sanitaire and ESN discovers the benefits of being a group, while the Left plots to threaten the Greens’ position.

- The political centre (the Berlin-Paris axis) has weakened, which allows for new polycentric majorities to emerge, including from Warsaw (security) and Rome (migration).

[1] Piotr Maciej Kaczyński (2019), ‘The EU after the elections: a more plural Parliament and Council’, Elcano Royal Institute, Madrid.

[2] The European Council candidate for the presidency of the EC was Ursula von der Leyen, and the EPP candidate for the EP presidency was Roberta Metsola. Both were confirmed for their respective second mandates during the Parliament’s first plenary session on 16-19/VII/2024.

[3] Piotr Maciej Kaczyński (2024), ‘Long in the Tusk: the Polish PM’s experience is coming to the fore’, Balkan Insights, 15/VII/2024.

[4] Nathalie Tocci (2024), ‘Meloni was on the best behavior – now her mask is starting to slip’, Politico, 22/VII/2024.

[5] See the Tusk-Mitsotakis letter to the president of the Commission on the Defence Union of 25/III/2024, the Czech initiative on ammunition purchase for Ukraine from February 2024, and the Finnish-Italian proposal against migrant smuggling of 22/IV/2024.

[6] ‘No majority in committee for proposed EU Nature Restoration Law as amended’, 27/VI/2023.

[7] ‘Nature restoration: Parliament adopts law to restore 20% of EU’s land and sea’, 27/II/2024. The Council of the EU formally adopted the agreement with the Parliament only on 17/VI/2024: ‘Nature restoration law: Council gives final green light’.

[8] ‘Abascal anuncia la incorporación de VOX a la nueva plataforma política Patriotas por Europa, que se constituirá como grupo en el Parlamento Europeo’, La Gaceta, 5/VII/2024.

[9] Interview with head of a national delegation in the ECR, 18/VII/2024.

[10] Anthony J. Constantini (2023), ‘Meloni’s Western nationalism’, Politico, 4/IX/2023.

[11] Emilio Ordiz (2024), ‘Alvise pide entrar en el grupo de Meloni en el Parlamento Europeo… y la decisión final será en septiembre’, 20minutos.es, 24/VII/2024.

[12] ‘ANO ani protestní strany s podporou von der Leyenové v čele EK nepočítají’, 14/VI/2024.

[13] ‘2024 European elections. Post election survey briefing’, Focaldata, 9/VI/2024. According to Eurobarometer Survey 91.5 (Sept 2019) the main motivations for voting in the 2019 elections were: (a) the economy; (b) climate change; and (c) the defence of human rights.

[14] Alvise Pérez, ‘Todo llega, paciencia’, x.com, 18/VII/2024.

[15] Eddy Wax (2024), ‘Zombies, wannabes, soldiers: which MEP tribe do you belong to?’, Politico, 22/VII/2024.

[16] European Council conclusions: ‘This formulation means that the European Council cannot deprive itself of its prerogative to choose the person it proposes as President of the European Commission without a change of the Treaty’, European Council, Leaders’ Agenda, February 2018.

[17] European Council June 2024 conclusions, 27/VI/2024.

[18] 401 votes for the candidate in the secret ballot, 284 against. See ‘Parliament re-elects Ursula von der Leyen as Commission President’, European Parliament Press Release, 18/VII/2024.

[19] Laura Tilindyte (2019), ‘Election of the President of the European Commission. Understanding the Spitzenkandidaten process’, EPRS, April.

[20] Eddy Wax & Hanne Cokelaere (2024), ‘Von der Leyen feels the squeeze as EU liberals implode’, Politico Europe, 24/VI/2024.

[21] ‘2024 European Elections. Post-election survey briefing’, Focaldata, 10/VI/2024.

[22] ‘Ursula von der Leyen, Europe’s choice. Political guidelines for the next European Commission’, 18/VI/2024.

[23] EPP Manifesto 2024, ‘Our Europe, a safe and good home for the people’.

[24] Olivia Gyapong (2024), ‘EU Commission Chief to withdraw the contested pesticide regulation’, Euractiv.com, 6/II/2024.

[25] ‘The Commission decision was pushed by the Warsaw government’, 13/II/2024.

[26] María Díaz Crego (2023), ‘Committees of inquiry in the European Parliament’, European Parliament, May.

[27] Samy Adghiri (2024), ‘Even Macron’s closest allies fear his brand is toxic’, Bloomberg, 26/VI/2024.

[28] Donagh Cagney & Max Griera (2024), ‘Green Deal 2.0: Spain’s Ribera lays down vision for next Commission’, 15/IV/2024.

[29] Samuel Stolton (2024), ‘Why Donald Tusk wants to be the EU’s gatekeeper’, Bloomberg, 4/VI/2024.