Theme

This paper looks at the various scenarios for debt mutualisation in the Eurozone beyond 2018, considering both the fiscal role played by the ECB on sovereign markets and the popular support for further integration.

Summary

This paper summarises the main options that literature and policy makers have explored to implement common debt issuance in the Eurozone. It describes the role that monetary policy is playing as a fiscal tool and why it is not sustainable due to the limitations that inflation and populism impose on political stability and debt sustainability. The current economic and institutional environment requires some form of debt mutualisation to avoid the reappearance of sovereign crises. The balance between monetary normalisation and debt mutualisation should allow a soft transition from ECB’s sovereign interventions to some form of fiscal solution ‘from the centre’.

Analysis

Following the election of Emmanuel Macron as French President, the debate about the future of the Eurozone regained momentum. The pro-European policies supported by the new French administration have found a perfect complement in the new German government coalition. Policy-makers and researchers are leaking and publishing new proposals on how to enhance the Eurozone’s institutional framework to transform it into an optimal currency area.

Among the different policy options currently under discussion, debt mutualisation seems to be losing political interest in favour of other proposals, like tax reform or the creation of the so-called European Monetary Fund (EMF). Although these efforts are welcome, the current economic and institutional environment requires some form of solution ‘from the centre’ to ease sovereign market conditions, in the long term, and to reduce dependence from the European Central Bank (ECB), in the short term.

This paper studies the different scenarios for debt mutualisation in the Eurozone beyond 2018. The main question it tries to answer is whether the current sovereign debt stability is sustainable, given the lack of political consensus about further fiscal integration and the inflation target to which the European Central Bank (ECB) is committed.

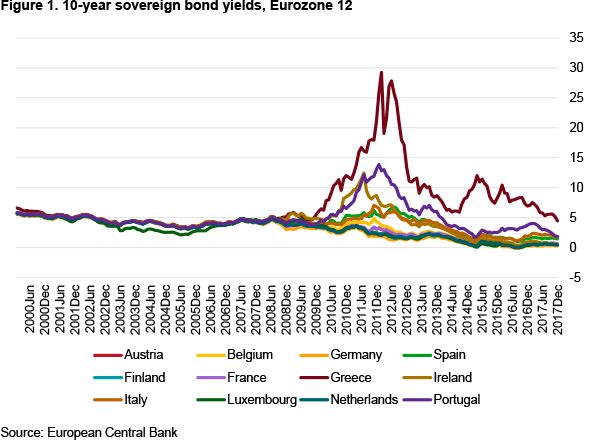

The current situation of debt markets, shown in Figure 1, is the result of the ECB’s intervention as well as of better macroeconomic fundamentals. Sovereign yields are now lower and more stable than ever before. The reduction in sovereign yields experienced from 2012 is correlated with several political and monetary measures (the announcement of the Outright Monetary Transactions –OMT– programme, the first steps of the banking union, German support for ECB stimuli, etc) designed to alleviate the sovereign debt burden. The stability achieved by this set of policies is, however, very fragile.

The first reason for this fragility is the ECB’s commitment to its inflation target. The OMT and Public-Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) are providing a strong support to debt markets, but each measure has a common goal: to keep inflation rates close but below 2%, the main mandate of the European monetary authorities.

The second reason is the momentum being gained by populist and anti-European parties. This is limiting the scope of the policies that traditional forces can push. Left-wing populist party criticism of Quantitative Easing (QE) suggests that it only favours the rich and gives special credit conditions to banks, without really helping society. Right-wing populist parties from core Eurozone countries suggest that the risk of high inflation derived from QE is too dangerous to be ignored. Both groups of parties reject any kind of debt mutualisation, for different reasons, as will be explained later.

What are the alternatives to the ECB’s stabilising role in debt markets, if inflation requires a rapid monetary normalisation strategy? Is it possible to build a consensus deep and wide enough to create a mutualised public debt architecture under the current political climate?

Debt mutualisation: recent developments

Pro-European parties face an important challenge regarding debt mutualisation. States with lower financial needs find that any borrowing-at-the-centre mechanism would require their generosity, since it would mean covering highly indebted states for their excessive risk. Countries with higher public-debt-to-GDP ratios find that all of the mechanisms currently under discussion could increase the pressure on them to accelerate economic reforms, in exchange for the protection received, through some kind of implicit or explicit conditionality. There is significant social pressure on both sides. Countries need to transfer financial sovereignty in a politically feasible way.

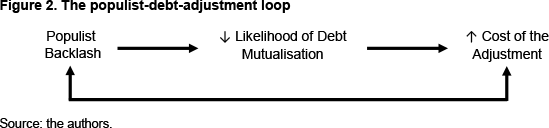

Anti-European parties, both from debtor and creditor states, try to take advantage of this situation. The lack of some kind of debt mutualisation mechanism increases the cost of the adjustment for member states; economic adjustment is harder to develop in a monetary union without the appropriate institutional framework.

Populist parties in debtor countries use that extra burden to undermine the credibility of the European project and to blame Europe’s institutional architecture for the economic situation of their countries. Populisms in creditor countries use the fragility in debtor states as an alibi to avoid further integration; differences are huge, they argue, and convergence is virtually impossible to achieve. Figure 2 shows this populist-debt-adjustment loop.

Over the past 10 years researchers have published several proposals to reduce sovereign volatility in the Eurozone. Gros & Micossi (2008) suggested the creation of a European Fund as an answer to the US Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP). This fund would issue bonds with the explicit guarantee of all Eurozone member states. Weizsacker & Delpla (2011) and Bofinger et al. (2011) studied the creation of a double-tranche security for European public debt that would allow countries to refinance their debt in excess of 60% of GDP. For Philippon & Hellwig (2011) the best way to increase checks on risks, both in terms of magnitudes and in terms of effective control, would be the introduction of Eurobills –common debt with maturity of less than a year–.

This first wave of proposals does not provide an answer to the two main challenges that policy-makers need to tackle to make debt issuance politically feasible: moral hazard and free riding. The second wave of proposals, all of them published from 2016 on, take into account these two problems.

The ESBies concept developed by Brunnermeier et al. (2016) does not require major changes in the current treaties, which would make it easier to implement. Mutualised bonds could be created by a new agency that would buy debt from different eurozone countries and issue, in exchange, two different categories of assets: senior debt, with lower risk, and junior debt, for investors looking for a higher return.

Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2018) recently suggested the creation of a synthetic Eurozone safe asset that could offer investors an alternative to national sovereign bonds. The goal would be to introduce it in parallel with a regulation on limiting sovereign concentration risk. According to the authors, this system would not lead to a permanent transfer mechanism. National contributions would be higher for countries that are more likely to draw on the fund. This is far from the interests of peripheral Eurozone countries, since it does not offer enough budgetary autonomy beyond a small stabilisation fund.

Policy-makers have also shown their interest in some form of debt mutualisation. The European Systemic Risk Board has recently published a proposal (ESRB, 2018), similar to the ESBies’s, to create a new class of safe financial asset intended to strengthen the euro area. The ECB would offer a plan for building government debt from member states into a security that could tackle default by one or more countries without sparking contagion.

Emmanuel Macron is pushing for a common budget in the Eurozone, a proposal that would probably require some kind of common debt issuance. The German position on the topic has changed in the past few months. Before the elections of September 2017, Angela Merkel was willing to accept only a small common budget with no debt issuance. The support that she needs from the Socialist Party (SPD) to retain her position as Chancellor is pushing the German Government closer to a larger European Budget.

The fiscal role of monetary policy

The level of political consensus that these proposals require makes them hard to implement. Policy-makers are studying different options to find the most socially acceptable, politically feasible and economically efficient one. Markets keep pushing for a solution.

Pressure peaked in the period 2010-12. The ECB reacted by announcing and implementing the OMT programme, the PSPP and the Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTRO). They eased market conditions and became a temporary solution for the lack of adequate borrowing-at-the-centre strategy. As De Grauwe & Moesen (2009) point out, the absence of a common backstop mechanism for each country’s public debt was a major issue that needed to be tackled.

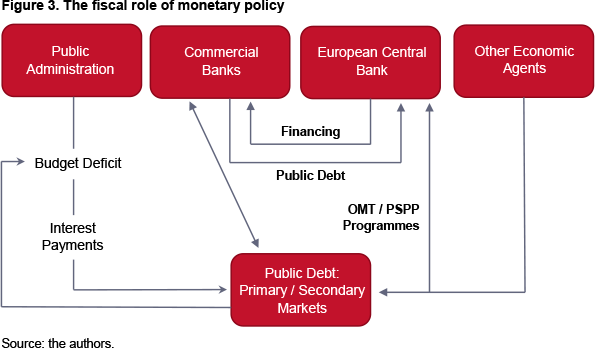

Figure 3 shows the relationship between public administrations, commercial banks and the ECB under the current conditions of public debt issuance. When a country runs a budget deficit, it needs to finance it through public debt issuance, which generates higher interests and, then again, a deeper budget deficit. Each country is responsible for its own debt with no guarantee from the centre. Only the ECB can calm sovereign markets with the protection provided through the various programmes already mentioned.

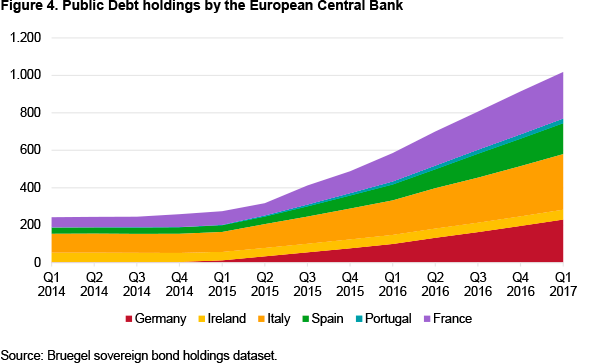

According to the Bruegel sovereign bond holdings dataset, by the end of September 2017 the ECB had bought €1.784 billion of bonds under its Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP), of which €193 billion were supranational bonds and €1.6 trillion were national government and agency bonds. Purchases of asset-backed securities reached €24 billion by the end of February, while holdings under the third Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP) amounted to €237 billion. Starting in June 2016, the ECB also added a Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP), which now stands at €116 billion. Figure 4 shows this trend in central banks’ sovereign bond holdings since the implementation of the PSPP.

Through the PSPP, the Eurosystem ‘intends to conduct purchases in a gradual and broad-based manner, aiming to achieve market neutrality in order to avoid interfering with the market price formation mechanism’ (ECB, 2017). Asset purchases provide monetary stimulus to the economy in a context where key ECB interest rates are at their lower bound. They further ease monetary and financial conditions, making access to credit cheaper for firms and households. This tends to support investment and consumption, and ultimately contributes to a return of inflation rates towards 2%.

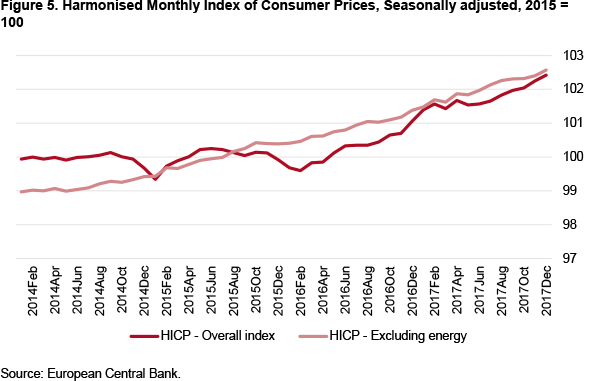

Figure 5 suggests that inflation is not rising fast enough to be a threat to the ECB’s price stability goal. Prices are growing slightly above 1% according to the latest available data. Headline inflation has been increasing since March 2016 while core inflation has been doing the same since the beginning of 2014.

According to the ECB’s January 2018 statement: ‘The strong cyclical momentum and the significant reduction of economic slack give grounds for greater confidence that inflation will converge towards our inflation aim. At the same time, domestic price pressures remain muted overall and have yet to show convincing signs of a sustained upward trend. An ample degree of monetary stimulus therefore remains necessary for underlying inflation pressures to continue to build up and support headline inflation developments over the medium term’. If inflation rises in the mid-term, the ECB would be forced to reduce its market interventions, including those focused on public debt stability.

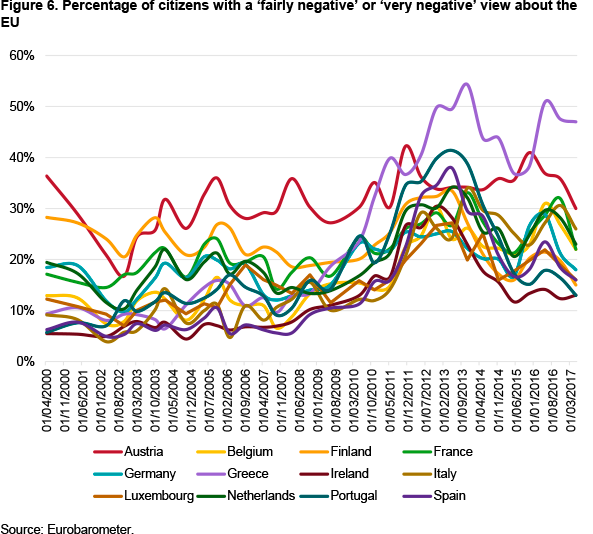

There is a second challenge for sovereign debt sustainability associated with the rise of anti-European parties promoting exit referendums and triggering political uncertainty with a critical message about monetary and political integration. Figure 6 shows the percentage of citizens in each country with a ‘fairly negative’ or ‘very negative’ view of the EU.

Negative views about the EU experienced their lowest point in the period 2003-07. After that, once the crisis began, they grew dramatically before moderating from 2013 on. The animosity against the European project was, at the end of 2016, higher than in 2000 in most Eurozone countries. There are two cases where negative views are particularly high still today: Greece (at 47.5%) and Austria (30%).

In the Netherlands, Italy and France around 30% of the population have ‘negative’ or ‘fairly negative’ views about the EU. In half of the original Eurozone member countries there is significant opposition to the European project that needs to be managed and that could eventually limit the scope of the policies implemented, such as bond buying from the ECB, and act as a barrier to deeper integration.

Scenarios for fiscal union

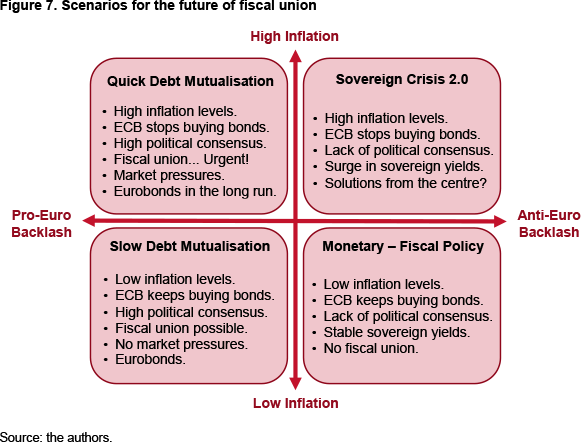

There are two important limitations to the ECB’s role in sovereign markets, as mentioned above. The first is the appearance of high inflation that might lead the Central Bank to normalise monetary policy faster than expected. The second is the awakening and development of anti-EU parties that can limit ECB market interventions or prevent further sovereign integration.

The joint analysis of both threats offers four scenarios for the future of debt mutualisation. Figure 7 shows the options. The vertical axis stresses two possible outcomes for inflation in the coming quarters: inflation rates can rise above the ECB’s target or stay below the 2% threshold. The latest data show that inflation remains subdued in the short term, but that it could accelerate during the second half of 2018.

The horizontal axis is the political one, showing the cases of an anti-Euro backlash capable of stopping debt mutualisation or ECB market interventions. During the first months of 2017 there was huge concern about the possibility that several anti-European parties could win the elections in the Netherlands, France and even Germany. The first weeks of 2018 reveal a more stable political landscape, with pro-European forces dominating the agenda. If a stable government is finally established in Germany, a three-year window would open for deeper economic integration. Italy remains the biggest concern, as the picture after the results of the 2018 election shows no clear government coalition.

In the ‘Quick Debt Mutualisation’ scenario, inflation rises above the ECB target and pro-euro resurgence allows policy makers to deepen fiscal integration without high political costs. Inflation requires an alternative to the fiscal role that the ECB has been playing since 2012. Eventually, the ECB must abandon its bond-buying strategy. However, thanks to the political consensus, a long-term solution for the public debt problem could be easily achieved. Market pressure would also help. The case for Eurobonds would be more plausible.

The top-right scenario shows a sovereign crisis renaissance. In this case, inflation is again above its target but there is insufficient political consensus for implementing any borrowing-at-the-centre mechanism or some form of fiscal union. The lack of action from the ECB plus the absence of solutions from the centre would ease the conditions for a new sovereign crisis.

In the bottom-right scenario an anti-European backlash dominates. This would be the case of a failed German government or a ‘Five Star plus Legga’ coalition in Italy, with aggravated anti-establishment policies. In this ‘Monetary-Fiscal policy’ case there are no short-term inflationary pressures. This would be the continuity scenario. The lack of political consensus would not allow a long-term solution from the centre, but the ECB could continue with its bond-buying strategy. This scenario would prevail as long as inflation remains subdued. Instability would be high, since monetary normalisation would move the Eurozone to the ‘Sovereign Crisis 2.0’ option.

In the ‘Slow Debt Mutualisation’ scenario there is low inflation and a high degree of political consensus. The ECB could maintain its bond-buying strategy without price-stability concerns. Social acceptance would offer a perfect environment for a slowly cooked debt-mutualisation process, without market pressures. Under these circumstances, the creation of some commonly issued debt security would be more possible.

Conclusions

This joint analysis takes into account only price stability and popular support for reforms. It disregards other limitations such as political willingness, technical difficulties and other negotiating barriers. From the authors’ point of view, the most desirable scenario would be the last one, the so-called ‘Slow Debt Mutualisation’. It would make the negotiating processes softer and allow member states to reach an agreement without market pressures. At the same time, it would let the ECB normalise monetary policy at the right time, when a political solution from the centre would be operational.

Monetary normalisation is unstoppable. The ECB needs to create monetary space. Inflation will eventually rise and get closer to its threshold. Policy-makers need to find a solution from the centre to sovereign-debt market stability that does not rely only on ECB policy. There is a real risk of a new sovereign crisis if the ECB withdraws from debt markets without the implementation of any alternative from the fiscal side. However, the ‘Sovereign Crisis 2.0’ is not expected to dominate over the coming years.

There is room for optimism for at least two reasons. First, the leaking of the ECB’s ESBies proposal shows that policy makers understand the relevance of the debate contained in this paper and are working to find an efficient solution. Even if it were a monetary solution, it would be a significant step ahead. Secondly, inflation remains subdued and populism relatively under control. The German government coalition is close to being operational. Italexit is no longer on the agenda. France and Germany have a three-year window to push for deeper integration. The need for some kind of solution from the centre to sovereign debt market stability is no longer questioned. The ‘Slow Debt Mutualisation’ scenario is at present the most desirable and likely. The depth and scope of such a common solution will depend on the evolution of political debate during the coming months.

Alfredo Arahuetes García

Senior Research Fellow, Elcano Royal Institute, and Professor of International Economy, ICADE (Universidad Pontificia Comillas)

Gonzalo Gómez Bengoechea

Professor of Economics, ICADE (Universidad Pontificia Comillas) | @ggbengoechea

References

Bénassy-Quéré, A., M. Brunnermeier, H. Enderlein, E. Farhi, M. Fratzscher, C. Fuest, P.-O. Gourinchas, P. Martin, J. Pisani-Ferry, H. Rey, I. Schnabel, N. Véron, B. Weder di Mauro & J. Zettelmeyer (2018), ‘Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform’, CEPR Policy Insight, nr 91.

Bofinger, P., L. Feld, W. Franz, C. Schmidt & B.W. Di Mauro (2011), ‘A European redemption pact’, Voxeu, November.

Brunnermeier, M.K., L. Garicano, P.R. Lane, M. Pagano, R. Reis, T. Santos, D. Thesmar, S.V. Nieuwerburgh & D. Vayanos (2016), ‘The sovereign-bank diabolic loop and ESBies’, CEP Discussion Papers dp1414, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

De Grauwe, P., & W. Moesen (2009), ‘Common euro bonds: necessary, wise or to be avoided?’, Intereconomics, vol. 44, May/June.

ECB (2017), ‘Implementation aspects of the public sector purchase programme (PSPP)’, European Central Bank, last updated 30/I/2017.

ESRB (2018), ‘Sovereign bond-backed securities: a feasibility study, vol. I: main findings’, ESRB High-Level Task Force on Safe Assets, European Systemic Risk Board, European System of Financial Supervision.

Gros, D., & S. Micossi (2008), ‘A call for a European Financial Stability Fund’, CEPS Commentary, October.

Philippon, T., & C. Hellwig (2011), ‘Eurobills, not eurobonds’, Voxeu, December.

Weizsacker, J.V., & J. Delpla (2010), ‘The blue bond proposal, Policy Contributions nr 509, Bruegel.