Theme [1]

This paper analyses the Chinese economy and its impact on the strategic triangle between China, the EU and the US, with a particular focus on electric vehicles (EVs).

Summary

As the Third Plenum of the 20th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party meets in Beijing, China is facing an economic slowdown, with the potential of triggering a deflationary spiral. This is due to ‘too much state and too little market’, which supresses the ‘animal spirits’ and curbs internal consumption. However, there is a paradox here. The more the West tries to contain China, the more the Government increases its control over the economy and the more this leads to additional investment in industrial manufacturing. This in turn creates more overcapacity and enhances the tensions with the West. The current electric vehicle (EV) trade dispute is a good example of this, which also shows that while the US is trying to decouple from China by means of prohibitive tariffs, the EU is still in a de-risking mode involving graduated tariffs. The bloc is aware that if it is to meet its zero-emissions targets it needs to rely on (cheap) Chinese green technology, not least to spur competition among car manufacturers. Many European countries are also keen on attracting Chinese EV production to their shores. But there are still many risks. Will China generate local jobs? Will the EU and China agree on a joint data governance regime? And if Europe remains open to Chinese industrial manufacturing, will China open up its services sectors? Ultimately, China is at bay, but Europe cannot be its main lifeline.

Analysis [2]

There is no doubt that China is in dire straits. This will be the overarching sentiment at the reform-oriented Third Plenum of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China which meets from 15 to 18July 2024. Growth is weak and the structural problems are mounting: the real estate market is undergoing significant correction, local government debt is too high, post-COVID consumption has failed to pick up, youth unemployment is at historic highs, ageing is a ticking time bomb and while exports are booming, both the US and the EU are shutting their markets to Chinese products, generating increased anxiety among Chinese manufacturers.

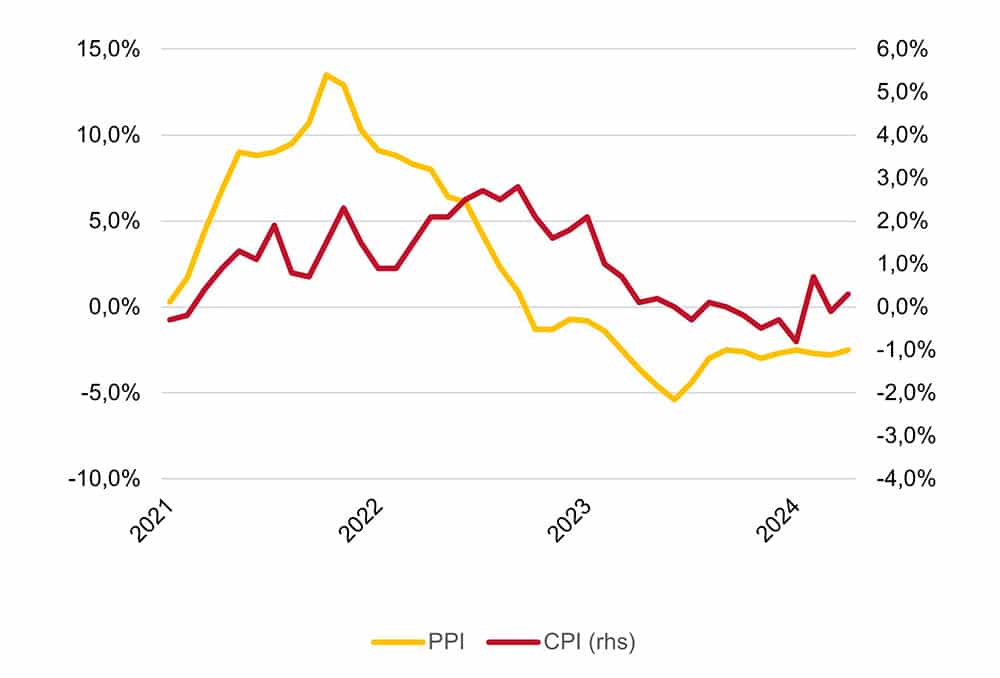

Figure 1. Producer and consumer price indices, 2021-24

This spring I had the opportunity to spend 15 days in China (visa-free for the first time) in order to analyse the situation on the ground. Given that China has become an even more hermetic place after COVID and its national statistics are increasingly questioned, it seemed necessary to visit the country to obtain a first-hand feeling of the current mood. And indeed, the pessimistic outlook was confirmed by my interaction with my interlocutors in China. Beijing and Shanghai are now cleaner, more modern and greener (I have never seen so many blue skies in my 15 years of visits to the country), but their citizens are less optimistic about the future. I saw many empty restaurants, very few Westerners on the streets and encountered many Chinese complaining about the state of the economy; and yes, I discovered lower prices (China is now a cheap destination) presaging a deflationary spiral, which made me realise that China is, indeed, at bay.

1. Who killed the Chinese economy?

The discussion in the West about China’s economic downturn has been framed by the debate started by Adam Posen in Foreign Affairs last year. His argument is that Xi Jinping has gone too far with his authoritarianism. The harsh zero-COVID policies and the crackdown on the big tech companies, epitomised by Alibaba founder Jack Ma’s disappearance in late 2020, have shown the Chinese population the true face of the Communist Party of China (CPC), and this has undermined their confidence in the future. This is the reason household consumption remains below 40% of GDP, despite new attempts to raise it, like the Dual Circulation Strategy proposed by Xi Jinping in 2020, one of the main aims of which was to increase domestic demand.

There is certainly some truth here. Many of my interlocutors in China (professors, think-tankers and business executives) would agree that there is now too much state and to little market in the Chinese economy. This is certainly the case in Shanghai, where the 2022 lockdown left many scars, and many businesspeople and entrepreneurs left the country or at least moved (part of) their wealth abroad, fearing that Xi might become like Mao and go down the totalitarian path. Many Chinese economists would side with Michael Pettis’ reaction to Posen’s article, however. They argue that China’s economy has reached the limits of export and investment-driven growth, and that the new growth engine must be domestic consumption.

As Pettis explains, under this interpretation, the intervention of the CPC in the economy is not the real problem (the party has been intervening for decades, and China’s growth miracle is partly a consequence of this state dirigisme) so much as the fact that it has not been able to change its policies when needed. One think-tanker said to me, ‘Of course, China needs to move from investment to consumption growth, but we need time to do this’. To which I responded: ‘But how much time do you need? Remember that former Premier Wen Jiabao said back in 2007 that the Chinese economy was “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable”. This was almost 20 years ago, and he repeated it 10 years ago and is likely to do the same in 2027 if nothing changes.’ As a matter of fact, two decades ago household consumption was also 38%, so very little has changed since then.

The reasons for this delay are of course to be found in the political economy of China. Changing the growth model of a country is never easy. Structural adjustments of this sort are painful and there are many vested interests that resist them. The CPC is fearful that more consumption, especially in services, might lead to less control. As a matter of fact, China’s party-state permeated capitalism has never abandoned the Bretton Woods regime of the post-WWII era. It has capital controls, a relatively controlled (and hence competitive) exchange rate and a monetary (and credit) policy directed towards export and (capital and infrastructure) investment to make China an industrial powerhouse. Resources are flowing from consumers to producers, and this is difficult to reverse, especially if the party perceives many risks in such a structural change.

2. It’s the political economy, stupid!

Focusing on what the party thinks is best for the country is key in China, which is why it is useful to turn to analyses more weighted towards political economy. Adam Tooze’s five-entry series entitled ‘Whither China?’ is essential in this context. In his view, neither Posen’s ‘authoritarian turn’ nor Pettis’ ‘Keynesian structuralism’ explain the current slowdown of the Chinese economy. To explain ‘why now?’, Tooze points much more to the sentiment of hubris. It is now forgotten in mainstream accounts in the West, but China managed COVID much better than most Western countries in 2020 and 2021. The idea that China applied permanent and draconian lockdowns over three years is wrong. There was much more mobility, and economic activity, than in the West. The problem was that the until-then successful ‘dynamic clearing’ model was unfit to fight the Omicron variant of the virus. And yes, the lockdown in Shanghai was unnecessary.

But we need to remember that in Summer 2020 there were mega-parties in Wuhan –of all places– and this ‘big victory’ of the Chinese people against COVID, according to Tooze, went to the heads of the Chinese leaders. As he puts it: ‘With its mandate from heaven confirmed, Xi’s regime turned bold. In May 2020 Xi’s regime pivoted to address three perceived threats to its undisputed and broadly popular rule: tech oligarchs, Hong Kong, and the giant housing bubble’. And indeed, the record shows that in June 2020 Beijing passed the Hong Kong National Security Law, in August it introduced the three red lines to reduce leverage in the real-estate market, which burst the bubble, and in November it halted Ant Financial’s IPO and Jack Ma disappeared as a public figure. So the story is much more that the party, sensing certain vulnerabilities (calls for independence in Hong Kong, too much power in the hands of tech oligarchs and an unsustainable real estate bubble), used this opportunity to assert its authority and increase its control. This brings us back to the thesis of ‘too much state and too little market’, but this time with the political economy dimension incorporated into the analysis.

This political economy-focused analysis also shows that the CPC obsession with more control precedes COVID, and even the advent of Xi Jinping. 2008 is an important historical year here, and the start of what Jiang Shigong, an influential intellectual in China’s New Left and a major apologist for Xi Jinping, has dubbed ‘The Critical Decade’, which culminates in 2018 with Donald Trump’s open trade and tech wars against China. In 2008 China showed its renewed might with the Olympic Games and in the same year the US evinced the unsustainability of its financial-led capitalism with the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Fear in the US and again hubris in China triggered a negative downward spiral, led by geopolitical hawks on both sides, which is still in play to this day. In my view, US apprehension about China’s rise and its incompatibility with the US-led so-called (although never fully completed) International Liberal Order had already commenced a few years after China joined the WTO. We should not forget that Ben Bernanke was already putting forward his Global Savings Glut theory (a direct critique of China’s state capitalism) in 2005. But yes, 2008 is certainly a tipping point, at least in the eyes of many Chinese policymakers and intellectuals. As Jiang Shigong argues, Obama’s ‘Pivot to Asia’ and ‘Asia-Pacific rebalancing strategy’, including the promotion of the TPP and support for the ‘Sunflower Movement’ in Taiwan and the ‘Umbrella Movement’ in Hong Kong, were all part of a series of actions to ‘contain China’s rise’.

In reaction to this, China started to fortify its defences and bolster its offensive capabilities. On the tech front, in 2010 the Chinese government –already confident that Baidu, the local company, was a sufficiently strong alternative– made sure that Google would not be able to operate freely in the country. This was two years before Xi Jinping came to power. Later, under his leadership, China became more deeply entrenched. On the military front, China started to build its own aircraft carriers and militarise islands in the South China Sea to break the US’s ‘absolute control’ over the strait of Malacca. On the geopolitical front, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), its boldest foreign policy endeavour to date. But more importantly, as Jiang Shigong also highlights, with the 18th National Party Congress in 2012, the focus turned inward. This manifested itself in a closing of ranks, imposing discipline and strengthening the cohesion of the party and country to prepare for the ‘great struggle’ against the US. Over the next five years, the party became much stronger, as was acknowledged at the 19th NPC in 2017. But this made China more alarming in the West, paving the way to Trump’s ascent and his 2018 anti-China crusade. Again, hawkishness fed hawkishness.

And, as already mentioned, this spiral is still present today. Speaking to a leading International Relations scholar from Renmin University there was a concession that the state has expanded too much in China and this is stifling the economy. But he also insisted that we need to understand ‘why’. And in his view, ‘geopolitical competition promotes more state intervention in China’. In this regard, the Biden years have been as tough, or even tougher, for China than the preceding period under Trump. His National Security advisor, Jake Sullivan, explains that the US containment strategy vis-à-vis China is based on a ‘small yard and high fence’ approach. But the yard seems to expand every few months, ranging from inward investment prohibitions to export controls and even to outward investment restrictions. And this makes it very difficult for those calling for more openness in China. The party is obsessed with national security and operates under a strong siege mentality, and this is undermining domestic confidence. As Zongyuan Zoe Liu, reacting to Posen’s piece in Foreign Affairs argues, tensions around Taiwan have ‘stoked a gloomy perception in China that armed conflict is inevitable’, and increased Western negativity toward the country ‘contributes to the Chinese population’s mass loss of confidence’.

Hence, we have now entered a vicious cycle. The more the US and its allies try to contain China, the more state intervention there is in China; the stronger the voices for discipline and control and the weaker the voices for openness and reform. This is likely to be the outcome of the Third Plenum. And this in turn will further undermine household and business confidence, reduce domestic consumption and fuel the deflationary trend.

3. Implications for Europe

This negative downward spiral, which keeps domestic demand subdued, pushes China to double down on its investment-led growth model. Thus, despite the real-estate sector contracting significantly, the reality is that the very high investment levels in China have not decreased. What we are seeing is that bank loans have now shifted from the real-estate sector to the industrial sector, which makes China an even bigger manufacturing and export powerhouse, a situation that creates enormous tensions with its trading partners. Michael Pettis makes the point by highlighting the following numbers. With an economy of US$18 trillion, China accounts for roughly 18% of global GDP. The problem is that it accounts for only 13% of global consumption, while it is responsible for 32% of global investment and an astonishing 31% of global manufacturing. In conversations with Chinese economists, they tend to downplay China’s overcapacity. Their regular argument is that China has a competitive advantage in manufacturing, and this is the reason it exports so much. At one of the meetings with think tanks, a participant raised the example of South Korea and Samsung. South Korea is good at building smartphones and hence it exports far more than it consumes. Samsung has a huge global market share, but no one in the West is saying that South Korea has a huge overcapacity, he told me.

But this is precisely the point. China is not South Korea, nor the Netherlands for that matter, which has an oversized export sector too. The second biggest economy in the world cannot have such an asymmetry between its domestic consumption and its export capacity. And this is particularly a problem for the EU, which still has a strong industrial base, and a significantly more open economy than the US. We should not forget that trade as a percentage of GDP is only 27% for the US, while for the EU it stands at over 40%. This dependence on trade is a vulnerability for the EU, which has only increased over the past 20 years (in 2002, it was 69%), and places many European countries in the crossfire in the trade and tech wars between the US and China. Of particular concern in recent years is the large deficit in goods that the EU has with China, which reached the record level of close to €400 billion in 2022, although it dropped to almost €300 billion in 2023. China has enormously upgraded its industrial capacity over the past decade and the fear in Europe is that what happened to the textile, solar panel and wind turbine sectors –to name a few– will also occur in the car and aircraft manufacturing industries: essentially that China will move from net importer to net exporter in these sectors.

This is already happening in the car industry. China is now the biggest market, producer and exporter of electric cars –the most likely future path of the sector– and the EU is the biggest destination for China’s overcapacity. This has led to the inevitable. For years I have been telling my Chinese counterparts in my visits that if China does not open up, the EU will close down its market, and this is happening at great pace. Chinese investments in the EU peaked in 2016 (the purchase of the German robotics company Kuka by Midea was the turning point), and since then the EU has increased its defensive trade and investment mechanisms: first with the inward investment screenings and the 5G tool kit; then with the regulation of foreign subsidies distorting the internal market; shortly followed by the anti-coercion instrument (after China’s spat with Lithuania over the Taiwan trade office in Vilnius); and more recently with the possibility of higher tariffs on Chinese electric cars, and possibly wind turbines down the road. This puts the EU on the brink of a full-blown trade war with China. But, as I was told by a high-ranking official from the EU delegation in Beijing, the EU has reached its limit when it comes to Chinese promises about market openness.

One of the errors of many Chinese policymakers and intellectuals is to analyse international affairs through the US lens. The dominant view is that increased toughness against China is due to US pressure. This influence undoubtedly exists, but the Europeans –and the same applies to Indians, South Koreans and Vietnamese, to name a few– have enough of their own grievances against China to justify their criticisms. European companies, for example, have been complaining for several years now that the business environment in China is more difficult for them. One only needs to read the annual position papers of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China to obtain a detailed analysis of this trend. This comes on top of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has soured EU-China relations enormously. The Chinese have been slow in accepting that this conflict is existential for the EU, and for a long time have deemed that the Europeans were pushed by the US into supporting Ukraine’s military capabilities. This is an erroneous interpretation. The European support for Ukraine is genuine because many EU countries, Poland and the Baltic states in particular, believe that if Ukraine falls, they are next.

On the Ukraine question, European disappointment with China has been great. As someone from the EU delegation in Beijing also told me, the EU and China are supposed to be strategic partners. But if your neighbour gets beaten up by a bigger neighbour and you fear you may be next and your strategic partner turns a blind eye against this violation and continues business as usual or, even worse, intensifies its relations with the aggressor, then you think twice about whether this partnership is in your best interest.

Nonetheless, the strategic smart thinking in Europe is that we can ill afford a second flank of conflict with another great power. We have enough with Russia for the time being. China is also rethinking its strategy. Until the Ukraine war, China was operating with two different strategic triangles: one military, formed by the US, China and Russia; and one economic, comprising the EU, the US and China. But these two triangles are now difficult to separate. Given US hostility, China now needs the European market more than ever. This has now become strategic, so it will need to open up its market to European companies. This, at least, is what a top EU experts told me in Beijing.

4. What to do with electric vehicles (EVs)?

The EU has on numerous occasions stated that, in the words of Ursula von der Leyen, it wants to de-risk rather than decouple from China, as some in Washington want. The recent trade (and tech) dispute over the imports of Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) is a good example of this stance. While the Biden Administration has opted for preventive and prohibitive tariffs of 100%, treating China’s EVs (almost) as a national security matter (if Tik Tok is a threat, where does this leave smart Chinese vehicles?), the EU has adopted a much more technical, nuanced and moderate approach. The European Commission has proposed import tariffs of up 38.1%, on top of the existing 10%, so 48.1% duties for those Chinese brands that have not collaborated in the anti-subsidy investigation, like SAIC. But those that have collaborated (which include the European brands based in China and presumably Tesla) will be subject to import duties of 21% (31%) and BYD, the largest Chinese manufacturer, will pay only 17.1% (27.1%).

It is important to analyse the signalling sent by the EU here: (a) the calculation of the tariffs to a degree of specificity of 0.1% immediately indicates that the Commission wants this to be a technical (WTO-compliant) affair and not a geopolitical spat; (b) the tariffs are sufficiently low for Chinese brands to try continuing to penetrate the European market, while high enough to create incentives to produce in Europe (BYD and Chery are already planning to do so in Hungary and Spain, respectively); (c) BYD, the biggest Chinese EV manufacturer, will have a lower tariff, which means that it will act as the ‘catfish in the tank’ to spur competition in the European market; and (d) the Commission has kept the door of negotiation with Beijing open until 4 July, or even beyond, to avoid further escalation. Ultimately, the aim seems clear. The European Commission is aware that if it is to meet the net-zero emissions climate goal by 2050 and ban internal combustion engines in cars by 2035, the EU needs cheap Chinese EVs. But this entry needs to be gradual. Whereas in the last five years the market share of Chinese-produced EVs has climbed from 1 to 25% (including Western brands), and that of Chinese brands alone now stands at 11% and is likely to reach 20% by 2027, this pace of increase cannot be allowed to continue.

European carmakers need some more time to adjust. But adjust they must, and from a European perspective this competition is good. So, in many ways, the interdependence with China continues and is likely to do so in the future. 30% of German carmakers’ global revenues come from China, a percentage that is likely to fall. But it will continue to be substantial if BMW, Mercedes and Volkswagen want to survive the green transition. It is important to highlight here that the European car industry, which goes beyond Germany, neither initiated nor called for the anti-subsidy investigation, at least not publicly. On the contrary, in their 2023 manifesto they called for open markets and fair competition and, yes, for a European industrial strategy to be able to compete better and make Europe a production hub with its own supply chain autonomy (including mining, refining, components, assembling, recharging and recycling). They also call for technological neutrality, which is something that worries the industry as a whole, both in Europe and China. In conversations with EV experts in China, concerns were expressed about Europe’s inclination to favour local production rather than imports from China. They fear that Chinese manufacturers might commit to serious investments on European soil but then Trump (or even Biden) may exert pressure on the Europeans to ban Chinese cars on national (or in this case transatlantic) security and intelligence grounds, as happened with Huawei. The future (charging) infrastructure around electric (and autonomous) vehicles might be seen as critical.

Indeed, data governance is the elephant in the room that thus far has been skirted around in the public conversation, at least in Europe. The reason may be that in Europe there is little data sovereignty anyway, and, unlike in the US, there is no ambition to control the world’s key communication and intelligence networks. Nonetheless, how data produced by EVs is managed, stored and utilised will define whether we end up closer to de-risking or decoupling. Will Europe be able to find a joint standard and governance regime with China on this? This remains an open question. But the outcome will also determine whether China is a partner, competitor or strategic rival for the EU. Or all three at once.

Conclusions

The secondary and fieldwork analysis conducted for this research shows that the West, and the EU in particular, is confronted by a paradox. The more the strategic goal is to contain China, the more China feels besieged and the more the CPC tries to control the Chinese economy. This reduces the confidence of the Chinese consumer and induces the CPC to double down on turning China into an industrial powerhouse. And the more this occurs –a trend likely to be reinforced at the Third Plenum– the more the West is confronted by Chinese overcapacity in strategic sectors. The EV industry is a case in point. Faced by this, the US has decided to decouple from China (although this is not so easy: it still imports substantial numbers of batteries from China and Chinese manufacturers can channel their imports through Mexico) with 100% import tariffs, while the EU has opted for a de-risking approach, with lower and differentiated tariffs (from 17.1% to 38.1%, on top of the 10% already in place).

The signalling from the EU seems clear. Unlike the US, the European approach is WTO-compliant and aimed at initiating negotiations. The Europeans are also aware that if they want to meet their zero-emissions targets they need cheap Chinese cars to spur competition. They are also happy to see more greenfield Chinese EV production in Europe. This is the position of Spain, the second largest producer and exporter of cars in the EU. But this needs to come with certain conditions. First, the supply chain cannot be imported from China. This will not create local jobs, nor a local ecosystem that generates value. Secondly, a joint framework for data management needs to be agreed. Without this, cooperation will be difficult. Finally, the European Commission has signalled that it is willing to negotiate with China on these tariffs. The question is what can be gained. Lower state subsidies in China and increased Chinese production in Europe is a start, but the Commission needs to go beyond this. If China’s competitive advantage is manufacturing, that of Europe is services. China should open up these sectors if it wants to keep selling its cars in Europe with low tariffs. This could break the hawkish and protectionist spiral we are witnessing. But it will not be easy. China is at bay right now and views Europe as a strategic market, but if it does not want to open up, the EU cannot become its lifeline.

[1] Part of this study has been funded by the EU through the Horizon Europe programme and the ReConnect China project. The sole responsibility for the content of this document lies with the author. The European Commission and the European Research Executive Agency (ERA) accept no responsibility whatsoever for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

[2] I would like to thank Agustín González Agote for his research assistance and Federico Steinberg and Mario Esteban for their valuable comments. This research was partly funded by the EU under the Horizon Europe programme and the RECONNECT China Consortium.